Early benchmarking

How early benchmarking improves the accuracy of payroll employment data.

The economic problem

Survey data more timely; administrative data more comprehensive

Assessing the current state of the economy requires accurate and up-to-date measures of economic activity. However, it often takes months or years for the most comprehensive economic data to become available. As a result, early releases of economic statistics are often revised multiple times as more detailed information becomes available.

Employment is one of the most important indicators of economic activity. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) releases a payroll employment series known as the Current Employment Statistics (CES).[1] The most recent four to 18 months of the CES series rely on the CES survey, which is also referred to as the Establishment Survey or the payroll survey. This survey covers about one-third of the nation’s nonfarm employers, and the BLS uses this sample to estimate recent payroll employment.

More comprehensive counts of payroll employment become available later. The primary source of these data is the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), which compiles information from unemployment insurance records that firms file with their states. These data cover about 97 percent of nonfarm payroll employees, and data for the remaining 3 percent of nonfarm employees are obtained from other sources.[2] The QCEW relies on administrative data with broad coverage, so it offers more comprehensive employment information than the CES survey. The BLS revises its payroll employment numbers each March to incorporate this information. This annual process is known as benchmarking, and the resulting employment numbers are often referred to as the benchmarked employment data.[3]

For the state of Texas, the Dallas Fed improves on this process in one important way. The Dallas Fed updates its employment numbers quarterly using preliminary releases of the QCEW from the Texas Workforce Commission. This “early benchmarking” process ensures the Dallas Fed’s payroll employment estimates rely on the most accurate data available.[4]

The technical solution

Incorporate administrative data as soon as It's released

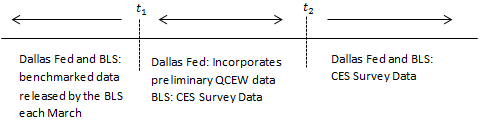

The timeline in Figure 1 highlights the composition of the Dallas Fed and the BLS payroll employment series, which may help clarify the differences between the data available from these sources. For all months through t1, both the BLS and the Dallas Fed use the benchmarked employment data that the BLS releases each March. For months t1 through t2, the Dallas Fed incorporates preliminary releases of QCEW data. In contrast, the BLS relies on CES survey data for months t1 through t2. Finally, preliminary QCEW data are not available for months after t2, so both the Dallas Fed and the BLS use CES survey data.

Sources of Data Across Time

The Dallas Fed links these different data sources to construct its complete payroll employment series. The BLS benchmarked data determine the baseline level of employment, and the Dallas Fed uses the data available after t1 to compute the percentage change in employment from one month to the next. Then, month by month, it applies these percentage changes to obtain an estimate for the current month’s employment. This allows the Dallas Fed to extend the BLS benchmarked data forward to obtain payroll employment estimates for recent months.

Real-world example

Level of early benchmarked data follows BLS; changes follow QCEW

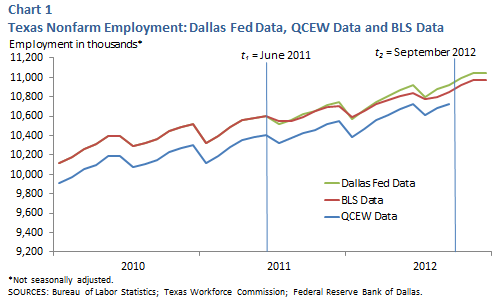

Chart 1 illustrates the data published by the Dallas Fed and the BLS as well as the level of payroll employment reported by the QCEW. Before January 2023, the Dallas Fed payroll employment series reports the benchmarked data available from the BLS, so the two series overlap. By looking at these months, it’s clear that the benchmarked level of payroll employment is higher than payroll employment in the QCEW. In fact, it’s about 3 percent higher because the QCEW covers 97 percent of nonfarm employees, and the BLS benchmarked data incorporate information from other sources to cover the entire population of nonfarm employees. Still, because the QCEW covers such a large portion of nonfarm workers, the changes in benchmarked employment closely follow the pattern of the QCEW. For January 2023 through September 2023, when the preliminary QCEW are available from the Texas Workforce Commission, the Dallas Fed uses the percentage change in these data to extend its payroll employment series. The reported level of payroll employment is still higher, consistent with the benchmarked data, but the movements follow the QCEW data. In contrast, the movements in the BLS series depart from the QCEW data because the BLS uses the CES survey data to estimate payroll employment. Finally, after September 2023, the QCEW data are no longer available, so the Dallas Fed also uses the movements in payroll employment observed in the CES survey data to continue its payroll employment series.

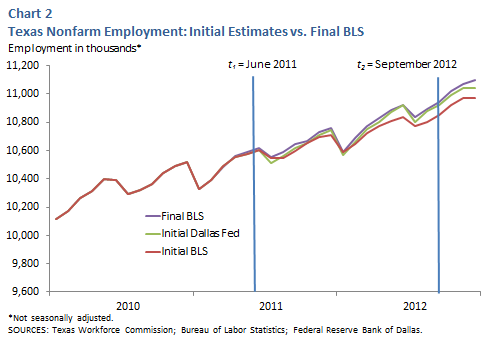

Dallas Fed's early benchmarked data closer to BLS's final release

Chart 2 illustrates how the Dallas Fed's incorporation of preliminary QCEW data affects its payroll employment estimates. This graph compares the original payroll employment estimates released by the BLS (initial BLS), the BLS benchmarked payroll data released each March (final BLS), and the Dallas Fed payroll employment estimates after early benchmarking (initial Dallas Fed). Because the QCEW covers such a large proportion of nonfarm payroll employment, incorporating this information sooner allows the Dallas Fed to produce payroll employment estimates that closely match the final benchmarked data released by the BLS each year.

Summary

CES survey data offer timely estimates of the level of employment, which are later revised. To better estimate Texas payroll employment, economists at the Dallas Fed rely on quarterly releases of administrative data available from the Texas Workforce Commission. By updating employment estimates quarterly using these data, the Dallas Fed’s process of early benchmarking ensures that its payroll employment estimates incorporate the most comprehensive information available.

Notes

- The BLS also provides employment estimates from a household survey. However, the Dallas Fed's process of early benchmarking is only applied to the payroll survey data. For more information on the differences between the household and payroll employment estimates, see bls.gov/web/empsit/ces_cps_trends.htm or bls.gov/news.release/empsit.tn.htm.

- See bls.gov/web/empsit/cestn.htm for more information.

- For more information on the BLS benchmarking process, see bls.gov/web/empsit/cesbmart.htm. This process necessitates a special seasonal adjustment procedure. For more information, see the DataBasics article "Two-Step Seasonal Adjustment."

- For more details on early benchmarking, see "Reassessing Texas Employment Growth", Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, July/August 1993. See also, "'Early Benchmarking'” the State Payroll Employment Survey," Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Seventh District Update, June 1, 2015.