COVID-19 Fuels Sudden, Surging Demand for Suburban Housing

Before the COVID-19 pandemic began, large metro areas across the country experienced sustained robust growth, with their city centers increasingly popular among college-educated and high-income households.[1]

The pandemic paused this long-term trend. As the health crisis took hold in March and intensified in April, stay-at-home orders and social distancing measures restricted homebuyers’ mobility, prompting many sellers to step back. U.S. home sales subsequently dropped precipitously.

The sales decline was uneven, occurring disproportionately around big cities but less so in suburbs and smaller metros. This may have been partly driven by stricter and lengthier lockdowns in urban centers that closed businesses and prevented home showings. Even as the national housing market robustly rebounded beginning in June, sales near major metro centers continued underperforming the suburbs.

New listings simultaneously began soaring, indicating an increasing number of city-center homeowners looking to sell. Consistent with the spatially divergent trends in sales and listings, suburban housing inventory fell rapidly. This depletion of available units was indicative of surging demand and stood in contrast to the less-robust activity in city centers.

Months later, a steady level of inventory near city centers signals an ongoing demand shift from large urban centers toward the suburbs in the wake of the pandemic.

Texas Housing Demand Shift

This sudden demand shift from urban centers has been a nationwide phenomenon and the subject of a recent paper by Sitian Liu and Yichen Su, which examined the impact of COVID-19 on decreased demand for housing in densely populated areas.[2]

The trend is particularly prominent in cities and states where the pandemic hit initially and where home prices were the least affordable. Though the virus did not initially surge in Texas until mid-June and home prices here are in line with the national average, the state also experienced a shift from urban centers.

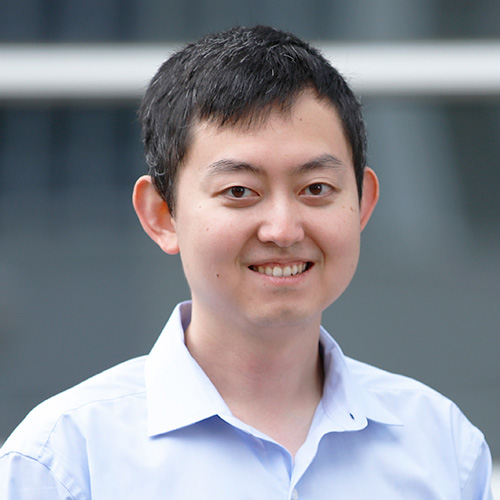

In the first two months of 2020—just before the pandemic hit the U.S.—Texas home sales grew near city centers and in the suburbs (Chart 1A).[3] When the pandemic arrived in March and April, sales dropped precipitously everywhere in the state due to stay-at-home orders and heightened uncertainty but fell disproportionately more near the city centers than the suburbs and urban outskirts.

The uneven decline was not solely driven by more stringent lockdown policies in city centers; new listings fell by a roughly similar magnitude in the urban centers as in the suburbs during the early months.

As lockdown policies eased and home sales partially recovered in June and July, new listings in city centers soared compared with the suburbs in Texas (Chart 1B). About that time, many Dallas Fed business contacts began reporting robust growth in new home sales activity in previously less-popular, far-flung locations.

The mounting new listings in urban centers likely reflected a growing number of residents looking to sell their homes. In August, new listings in urban centers were 16 percent higher than in August 2019, while those in the suburbs were flat to down.

Home inventories evolved in a pattern consistent with sales and new listings (Chart 1C). In January and February, overall inventories modestly trailed prior-year levels, likely due to strong housing demand. In March and April, owing to a pandemic-driven pause in home sales and lack of new listings, inventories remained relatively steady. As lockdowns were lifted and new listings soared in late spring and early summer, inventory dropped quickly in the suburbs while falling more slowly in city centers.

Greater Suburban Attractiveness

Living in dense, centrally located neighborhoods typically provides residents with the convenience of short commutes and plentiful amenities—easy access to shopping, dining, entertainment and other social activities. This attraction is closely tied to working in downtown offices and accessing restaurants, cafes, and arts and recreational venues.

Pandemic-related physical distancing measures that closed or restricted capacity at nonessential businesses signaled a sudden shift toward working from home. While most nonessential businesses are currently operational in Texas, surveys suggest that the nation is seeing a long-term change in teleworking patterns.[4]

Some large technology firms have allowed employees to work from home permanently, and many others are considering allowing telework for a greater share of their employees than before COVID-19, thereby lessening ties to central locations.

This shift to working from home motivated more homebuyers to seek the larger spaces found in more suburban locations.

The Transition to Remote Working

Technology has enabled a large segment of the workforce to undertake remote operations. As a result, commuting to central workplaces in major metro business centers isn't required.[5] [6] [7] With remote working rates expected to remain well above prepandemic levels, demand for housing near these urban centers has declined.

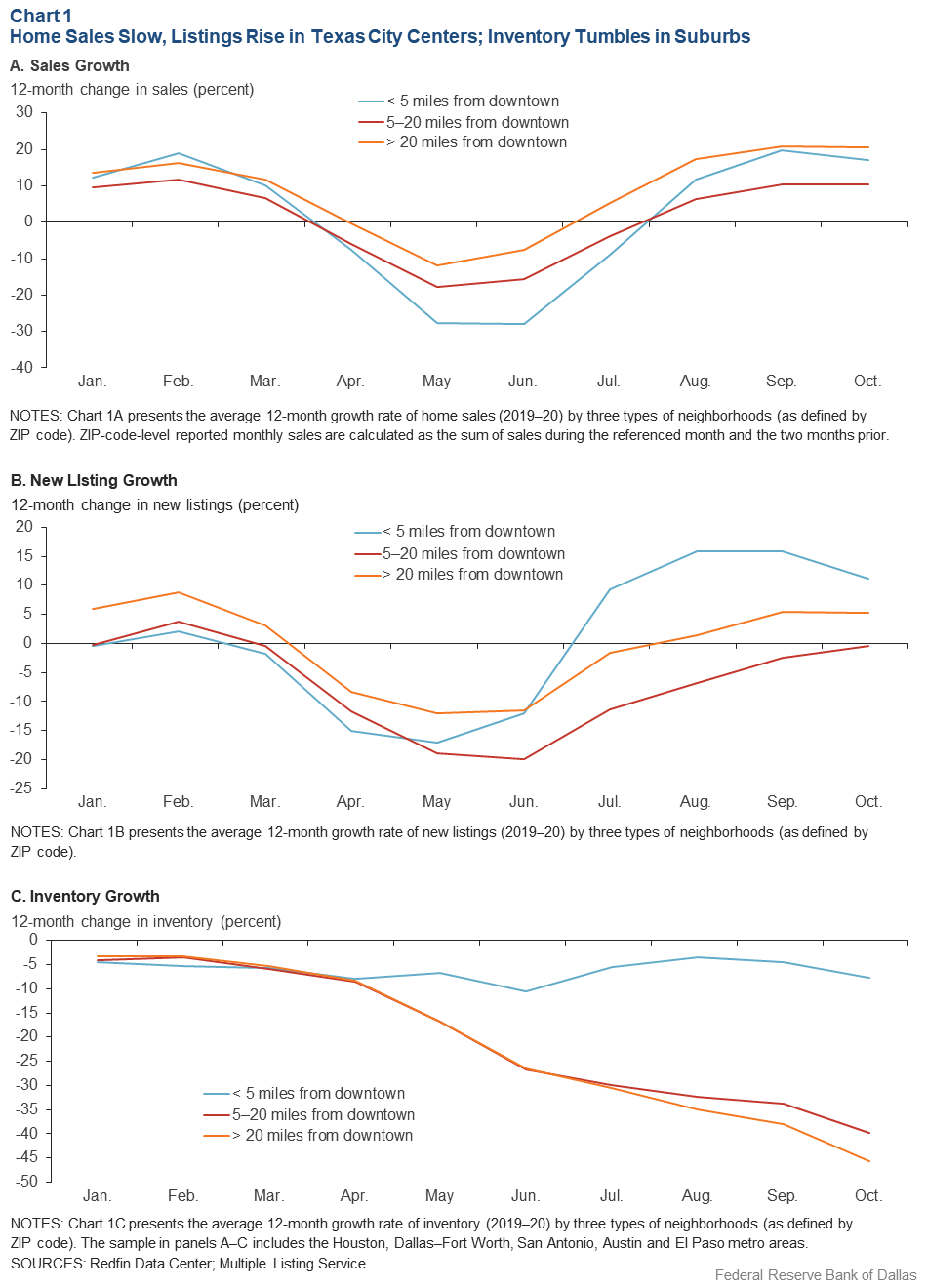

Geolocation data from a large sample of mobile devices provided by SafeGraph Inc., a data aggregation firm, show total visits to business establishments by distance from city centers in Texas’ five major metros.[8] The data are normalized by establishing the January 2020 number of visits as a baseline.

Trips to business establishments dropped everywhere following the outbreak of COVID-19 in March. However, the decline was more pronounced in the city centers. Although overall traffic staged a recovery in June, traffic at establishments in city centers remained relatively depressed compared with the suburbs.

This partially reflected a large reduction of commuting trips to the central business districts of the major Texas metros coinciding with greater teleworking from home. Moreover, because of the prevalence of telework-compatible jobs in city center locations, trips there declined more than those to suburban destinations (Chart 2).[9]

Amenity Access Less Attractive

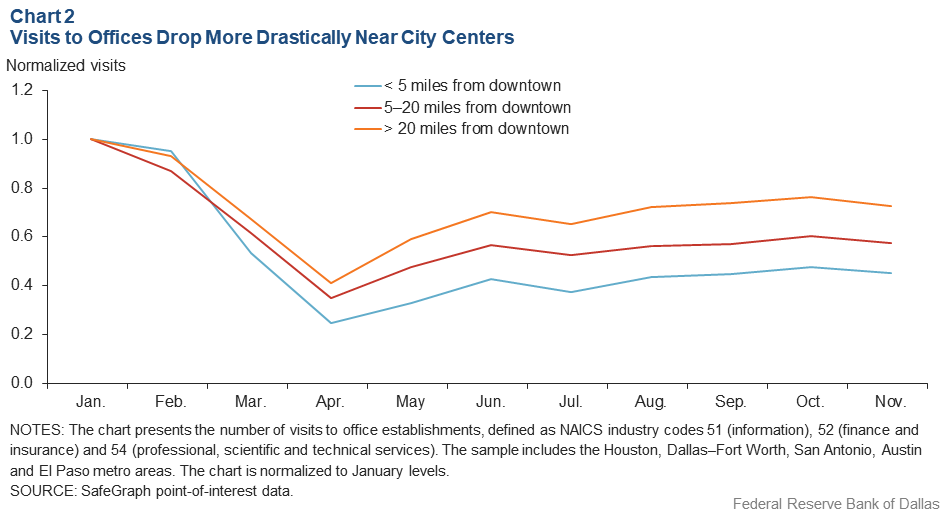

Another perk of living in central city neighborhoods is easy access to a great selection of restaurants, bars and other leisure amenities. Traffic to these amenities plummeted from mid-March through April with the lockdown and capacity restrictions.

Chart 3 shows the visiting trends of restaurants by distance to city centers. All amenity types—restaurants, gyms, grocery stores and parks—suffered a large drop in traffic, particularly those near city centers that only partially recovered as the pandemic continued.

The disproportionate drop in traffic to amenities in the city centers was partly the result of stringent lockdown policies and differing definitions of essential businesses in urban versus suburban counties. It also reflected elevated levels of pedestrian traffic in urban locations before the outbreak.

For instance, the Dallas and Houston mayors ordered the closure of various social establishments, and restaurants in Dallas and Harris counties were limited to drive-up service ahead of the statewide orders imposing similar restrictions.

While statewide shelter-in-place orders expired at the end of April, Austin and Travis County extended their stay-at-home orders beyond that date. Some of the largest urban counties in Texas also required residents to wear face coverings when in public in advance of a statewide directive.

Additionally, more rigorous definitions of essential businesses in urban locations meant that certain businesses such as car dealerships had to close in Dallas County but could remain open in other, mostly outlying areas of Dallas–Fort Worth.

The disproportionate decline in traffic to city locations also mirrored the absence of daily commuters who normally would have visited these establishments for dining and shopping. The recovery in visits to grocery stores and recreational establishments in city centers also lagged that of suburban locations, another indicator of more cautious reopening policies in urban centers.

Neighborhoods endowed with a large number of amenities generally tend to command higher rents and home prices.[10] As consumers hunkered down due to fear of infection amid commercial restrictions, high-priced homes with convenient access became less attractive and greater residential space became more appealing. These developments likely boosted demand for housing in suburban locations where amenities may be fewer but homes are larger and more affordable.

Indeed, demand for homes across the U.S. sharply declined in places with a large concentration of amenities such as restaurants.[11]

Single-Family Home Demand

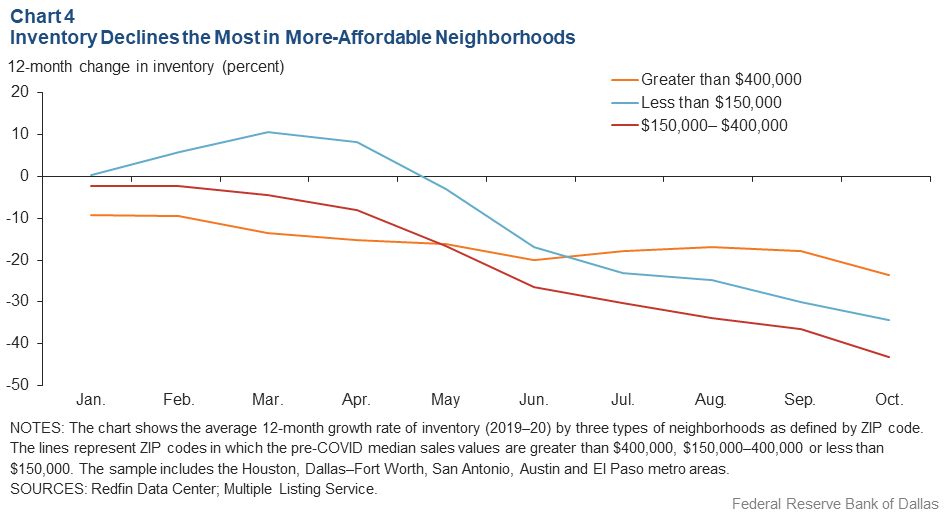

With a record number of people working from home and students studying from home, the need for flex space increased. Many builders note that buyers are looking for dedicated office and virtual school spaces in particular. This has increased demand for homes with more square footage in cheaper locations. Chart 4 shows inventory growth by neighborhoods’ pre-COVID home value. Inventory declines are more pronounced in areas with more-affordable homes.

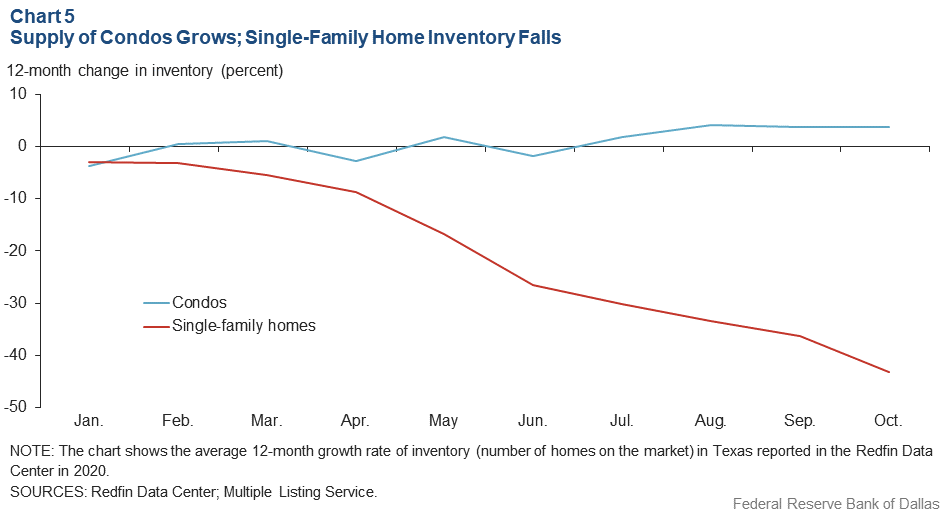

Not only is housing demand shifting toward more affordable neighborhoods, but demand for single-family homes has surged relative to condominiums which, like apartments, generally have more communal spaces such as elevators. This is illustrated in a dramatic inventory decline for single-family homes versus condos (Chart 5).

Rental Market, Homeownership

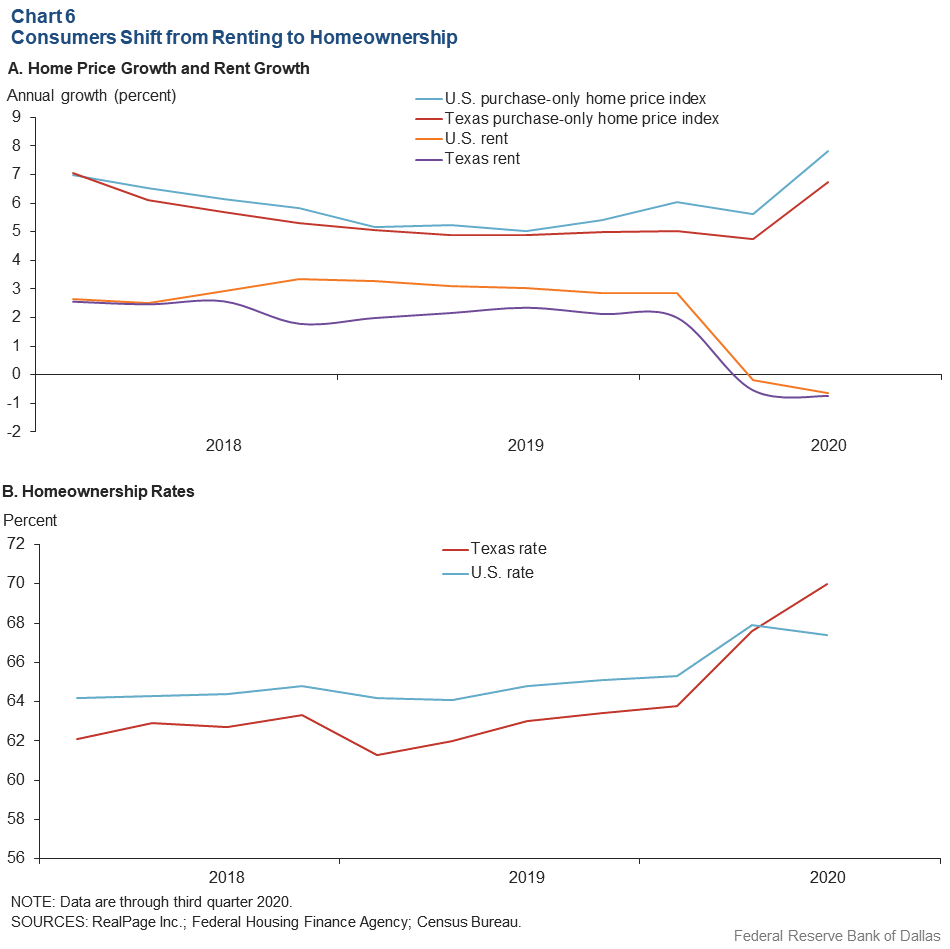

A sudden, large shift from renting to homeownership has accompanied the movement to suburbs and larger homes. Historically low mortgage rates have likely accelerated the shift, particularly among millennials—a sizable share of whom are in their early to mid-30s or turned 30 this year, a time of family formation.

The current era of low rates, unlike previous periods, is characterized by lagging demand for condominiums, indicating that low mortgage rates alone aren’t driving surging homeownership.

Net absorption of apartment units in second quarter 2020 was weak, though demand recovered in the third quarter. This recovery was more pronounced in suburban locations than the urban core. Still, occupancy remained below year-ago levels and rents were flat to down in most major Texas markets in the third quarter (Chart 6A).

Meanwhile, Texas home prices rose 6.7 percent in third quarter 2020 from year-earlier levels, while U.S. prices increased 7.8 percent. Homeownership rates in Texas and the nation rose notably in second quarter 2020 (Chart 6B). The national two-quarter increase from the first to third quarter—2.1 percentage points—roughly equaled the four years of gains in the homeownership rate from 1997 to 2000. Rarely has an increase of major magnitude occurred this rapidly during instances of declining and low mortgage rates.[12] The two-quarter gain was even larger for Texas, 6.2 percentage points.

Future of City Centers

The pace at which housing demand in city centers recovers depends on the trajectory of the pandemic and the public’s willingness to visit crowded venues, including workplaces. If the pandemic drags on for an extended period, the city center housing market may continue underperforming relative to the suburbs.

The longer-term impact of the pandemic on the future of cities is more uncertain. The pandemic has introduced teleworking to professions that typically had not adopted it. As employers and employees adapt to distance-compatible formats of work, such arrangements could become a permanent option for many in the post-pandemic era.

Employers anticipate that 21 percent of their employees will work remotely after the pandemic, compared with 8.3 percent pre-COVID-19, according to the Dallas Fed’s Texas Business Outlook Survey in August. If commuting to the office becomes a thing of the past for a sizable proportion of workers, it could depress housing demand near central business districts in the long run.

Still, the demand for leisure and consumption amenities will likely recover once the pandemic ends. Numerous research papers have shown that the prosperity of urban centers has increasingly been driven by the value of amenities there. As long as consumers’ appetite for food, entertainment and services returns—which is likely to happen following the adoption of a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine—activity and demand for housing in city centers will be poised for a recovery.

Notes

- See “Gentrification Transforming Neighborhoods in Big Texas Cities,” by Yichen Su, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Fourth Quarter 2019.

- See “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Demand for Density: Evidence from the U.S. Housing Market,” by Sitian Liu and Yichen Su, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Working Paper no. 2024, August 2020.

- The metros included are Austin, Dallas–Fort Worth, El Paso, Houston and San Antonio. The home sales, new listings and inventory data are obtained from Redfin Data Center. Sales and new listings data for each month at ZIP code level is the three-month sum ended with the reported month. For example, the number of sales reported for January 2020 is the total sales ranging from Nov. 1, 2019, to Jan. 31, 2020.

- See “What 12,000 Employees Have to Say About the Future of Remote Work,” Boston Consulting Group, Aug. 11, 2020, accessed Oct. 29, 2020, and “From Immediate Responses to Planning for the Reimagined Workplace,” Conference Board, June 2020, accessed Oct. 29, 2020.

- See “Work from Home After the COVID-19 Outbreak,” by Alexander Bick, Adam Blandin and Karel Mertens, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Working Paper no. 2017, July 2020.

- See “Working from Home During a Pandemic: It’s Not for Everyone,” by Yichen Su, Dallas Fed Economics (blog), April 7, 2020.

- For information on how telework-compatible jobs are defined, see “How Many Jobs Can Be Done at Home?” by Jonathon I. Dingel and Brent Neiman, National Bureau of Economic Research, NBER Working Paper no. 26948. Both methods yield the same conclusion that central business districts contain a much larger share of telework-compatible jobs. See note 2.

- Since the SafeGraph dataset tracks the movement of mobile devices, not people themselves, the accuracy of visitation patterns depends on how often people carry their devices.

- We define offices as establishments classified with NAICS industry codes 51 (information), 52 (finance and insurance) and 54 (professional, scientific and technical services).

- See “The Rising Value of Time and the Origin of Urban Gentrification,” by Yichen Su, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Working Paper no. 1913, October 2019. Also see “Urban Revival in America,” by Victor Couture and Jessie Handbury, Journal of Urban Economics, vol. 119, September 2020, and “The Determinants and Welfare Implications of U.S. Workers’ Diverging Location Choices by Skill: 1980–2000,” by Rebecca Diamond, American Economic Review, vol. 106, no. 2, 2016.

- See note 2.

- Some doubt may be cast on the validity of the magnitude given that the pandemic might skew the sample of survey respondents, but a dramatic homeownership increase is apparent in the data.

About the Authors

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: https://www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2020/swe2004.