How PPP loans eluded small businesses of color

An El Paso small business owner who’d had a bad experience with student loans was hesitant to apply for a federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan early in the COVID-19 pandemic. “I’m wary of government,” said the owner of a translation services company, one of the small business owners of color at a Federal Reserve roundtable who cited pain points that discouraged them from taking full advantage of the program. Some participants didn’t understand the PPP particulars, others pointed to a language barrier and still others were simply unaware of the program.

Research indicates that the PPP, which closed to applications May 31, 2021, was critical in stemming unemployment for firms able to receive the loans. But as we explored in a prior article, the PPP may not have been utilized equally across demographics in Texas. While we had anecdotal reports that minority-owned firms faced barriers in accessing the program, data limitations at the time prevented a full exploration of the issue. However, with more detailed data from the Federal Reserve System’s Small Business Credit Survey (SBCS), we can now shed more light on the disparities faced by small business owners of color, or SBOCs, in applying for financial aid.[1]

Using national- and state-representative data from small business owners via the Federal Reserve survey, we found that SBOCs were in greater need of financial support than their white-owned counterparts, but they successfully accessed the PPP less frequently. The difference was a statistically significant 12 percentage points.

Small businesses of color are a sizable and important segment of the regional and national economies. They represent 28 percent of all small employer firms in Texas, a share that is 10 percentage points higher than in the U.S. Therefore, understanding why they experienced such barriers is important to future program design.

With data from the 2020 survey and insights from a series of roundtables that ended in April 2021, we assessed the experiences of these Texas small business owners of color in obtaining financial help in the early months of the pandemic.[2]

Pandemic experiences differ for small business owners of color

The effects of the pandemic and its ensuing economic crisis were widespread across industries, business sizes, tenure and ownership demographics. But the severity of the impact was not distributed evenly based on these factors. For example, Fed research has indicated that leisure and hospitality and brick-and-mortar retail were among the industries initially hardest hit.

Firms of color in worse financial condition

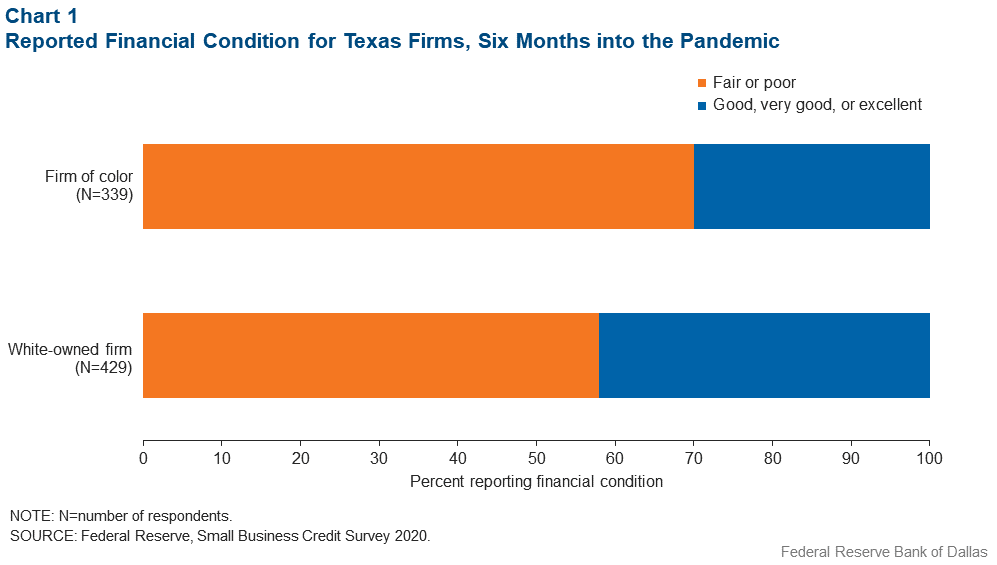

The pandemic also had a disproportionate effect on small businesses owned by people of color. About six months into the pandemic, a majority of small business owners described their financial condition as fair or poor, but SBOCs were 12 percentage points more likely to do so (Chart 1).

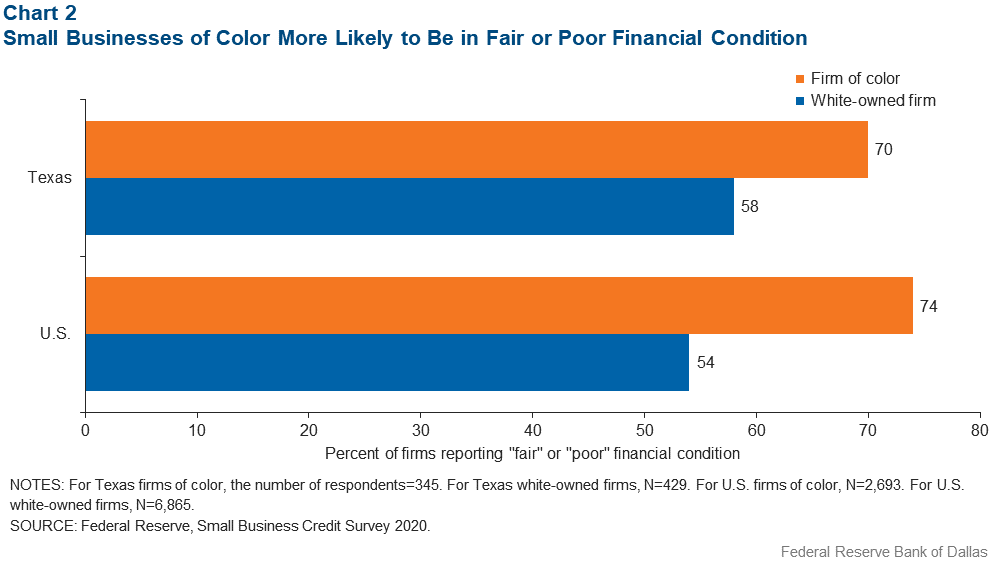

While 58 percent of white-owned firms in Texas indicated they were in “poor” or “fair” financial health, 70 percent of SBOCs did the same. This disparity is smaller in Texas than in the country at large (Chart 2).

We can see these conditions reflected in several other indicators. The first is the high share of firms reporting decreased sales due to COVID-19. In Texas, 83 percent of small employers of color reported decreased sales due to the pandemic, compared with 77 percent of white-owned businesses. Secondly, SBOCs reduced staff at a higher rate in Texas: Half of SBOCs reported reducing head counts in the prior 12 months, compared with 40 percent of white-owned firms.

There are plenty of reasons for the relatively larger financial difficulties facing SBOCs. It’s difficult to assess the discrete impact of individual factors, but compared with white-owned businesses, they include, on average:[3]

- A weaker prepandemic financial position.

- A concentration of SBOCs in industries hit particularly hard by the shutdowns.

- Fewer years in operation.

- Smaller average size in terms of both revenue and employees.

- Differences in access to the Paycheck Protection Program.

Texas firms of color less likely to apply for PPP

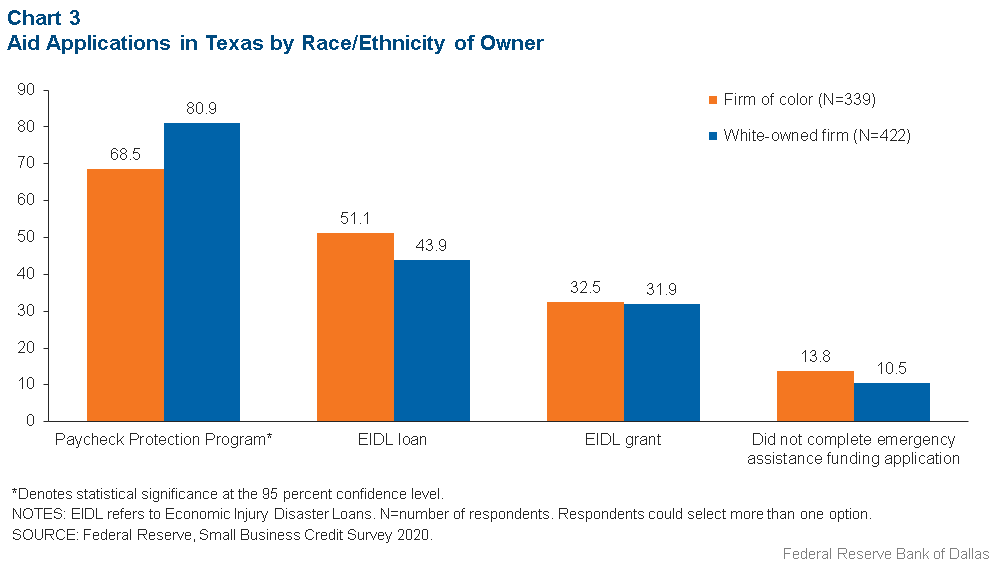

Seventy-seven percent of small employer firms surveyed said they applied for a PPP loan in Texas, a smaller share than across the U.S. (82 percent). But investigating this application share by race/ethnicity reveals a more significant gap.

As shown in Chart 3, white-owned firms surveyed were 12 percentage points more likely to say they applied for PPP loans than did firms of color (81 percent versus 69 percent). The reasons nonapplicants gave for not seeking a loan differ by race/ethnicity. The top reason white-owned firms did not apply for PPP in Texas was an inability to qualify for the program and/or forgiveness. The top reason for SBOCs was confusion about the program. Additionally, SBOCs were twice as likely as white-owned firms to indicate that they were unaware of the PPP program and 60 percent more likely to say they could not find a lender that would accept their application. Finally, white-owned small businesses were twice as likely to indicate that they did not need PPP funding (Table 1).

Table 1: Texas Firms of Color Struggled More with PPP Application Process than White-Owned Firms

| Top Five Reasons for Not Applying to Paycheck Protection Program | |||

| Firm of color (N=107) | White-owned firm (N=71) | ||

| Reason (percent) |

Reason (percent) |

||

| Confused by program/process | 30 | Would not qualify for loan/forgiveness | 40 |

| Would not qualify for loan/forgiveness | 29 | Confused by program/process | 21 |

| Couldn't find lender to accept application | 18 | Did not need funding | 17 |

| Missed the deadline | 16 | Missed deadline | 13 |

| Unaware of program | 16 | Couldn't find lender to accept application | 11 |

| NOTE: N=number of respondents. SOURCE: Federal Reserve, Small Business Credit Survey 2020. |

|||

When we spoke to SBOCs through roundtables,[4] we heard many of these same pain points reflected. The structure of the PPP created difficulties for SBOCs, who were less likely to have a lending relationship with a bank prior to the pandemic. Many business owners reflected on the difference in customer service experienced at community banks versus large ones, and intermediary partners attributed that difference largely to a lack of incentive with PPP to prioritize smaller customers. Said one Dallas-based small business intermediary:

“Lots of big banks aren’t able to both meet the demand of larger customers and call back the smaller ones. Then you have community banks—they are in the hunt for new accounts. They want you in their bank. They want to grow. This is an acknowledgement for smaller banks; they understand small businesses don’t have resources, so this was their push to make relationships. Small banks were eager to work with them and get them loans.”

Language barriers also surfaced with SBOCs, most often Hispanic-owned firms and Asian-owned firms whose owners were not fluent in English. An inability to find a banker proficient in a language other than English may have led to increased rates of confusion about the application process for some firms.

Finally, for some SBOCs, a lack of trust in government institutions or banks presented a barrier. Several business owners indicated some hesitation in applying for PPP. The El Paso business owner who was wary of government because of a bad experience with student loans expanded on her comment:

“We need a lot more transparency in what to expect in the actual process from application to money granted and the future. Like [with] student loans, they said you need 10 years of public service [to repay], but it’s not that simple. When the government tells me my loans will be forgiven, I am not too trusting. Again, there’s been wariness because of the lack of transparency, and who knows how they’ll decide how all this ends.”

Others described the tenuous relationship with mainstream financial institutions. One small business owner from Fort Worth explained:

“People of color are affected because of the way banks have historically handled people of color. Add the pandemic to that, and they have a hard time [getting help from banks] who have rejected them in the past, making it an uphill battle.”

Interestingly, in both Texas and the U.S., SBOCs were more likely than white-owned firms to apply for the Small Business Administration (SBA) Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL). While the survey did not ask for more information on this, it’s worth noting that EIDL funding comes directly from the SBA (not through banks) and has a longer track record (long before the start of the pandemic). These factors may have made EIDL more appealing to firms confused by or apprehensive about the PPP program.

Texas SBOCs who applied for PPP less likely to receive funding

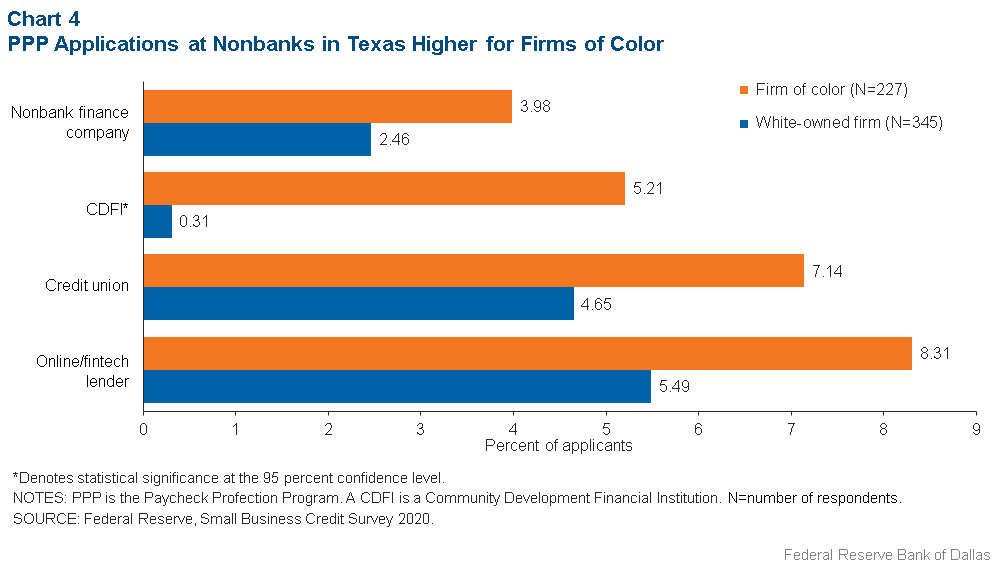

Although Texas SBOCs were less likely to apply for PPP than white-owned firms, a large majority (69 percent) still did. Banks were the most popular application source for both minority-owned and white-owned small businesses. However, applicants of color were more likely than white business owners to seek the funds through online lenders, credit unions and Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs).[5] Only the CDFI application rate difference is statistically significant (Chart 4).

One in 12 small business owners of color in Texas applied for PPP through an online lender, the most popular nonbank source.

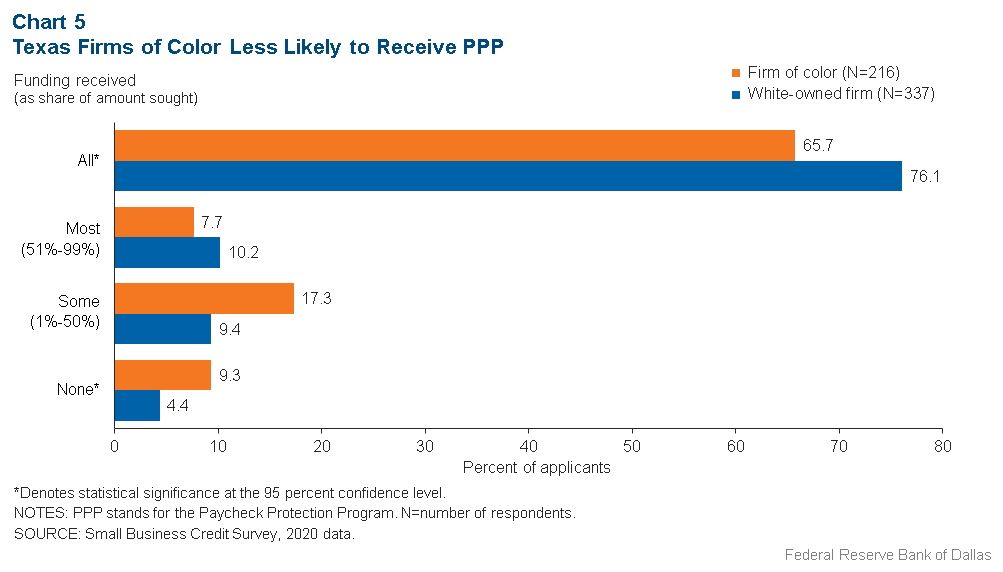

Compared with white-owned small firms, SBOCs were less likely to receive the full amount of the PPP loan requested (Chart 5). In fact, fewer than two-thirds of minority-owned firms received all the funding they applied for, compared with more than three-quarters of white-owned businesses. SBOCs were also more than twice as likely to be denied entirely for a PPP loan (9.3 percent versus 4.4 percent for white-owned firms).

The barriers SBOCs faced in applying to PPP may be similar to the barriers they faced in successfully receiving funding. Beyond customer service, language and trust issues, SBOCs also were less likely to have a prior lending relationship with a bank and often lacked the networks to help them navigate the confusing, changing application process. Firms of color also tend to be younger and smaller (in terms of both revenue and employees) than white-owned firms, which can mean less experience with the formal documentation or official business statements that are required for loan applications.

Traditional credit experiences

Beyond the emergency pandemic-related funding offered in 2020, firms also sought traditional financing, although at lower rates than in prior years. In Texas, 38 percent of firms applied for nonemergency financing, down from over 46 percent in 2019. Notably, a greater percentage of SBOCs applied for financing than white-owned firms (44 percent versus 35 percent), although the difference is not statistically significant.

It is useful to know why nonapplicant firms did not seek financing. Here, we find some stark contrasts between SBOCs and their white-owned counterparts (Chart 6).

While the majority of nonapplicant white-owned small firms in Texas indicated having sufficient financing, 63 percent of nonapplicants of color reported needing financing but something prevented them from seeking it. While both groups reported similar levels of debt aversion, SBOCs were five times more likely to suggest that the application process was a barrier. They were also more likely to report being discouraged.[6]

Discouraged borrowers do not seek funding because of assumptions that their applications will not be approved. While the sample size for Texas is not sufficient to discover the primary reasons for borrower discouragement, we can glean insights from the national survey. Nationally, while white-owned small businesses were most likely to report weak sales or too much preexisting debt, business owners of color more often pointed to concerns about low credit scores or insufficient credit history.

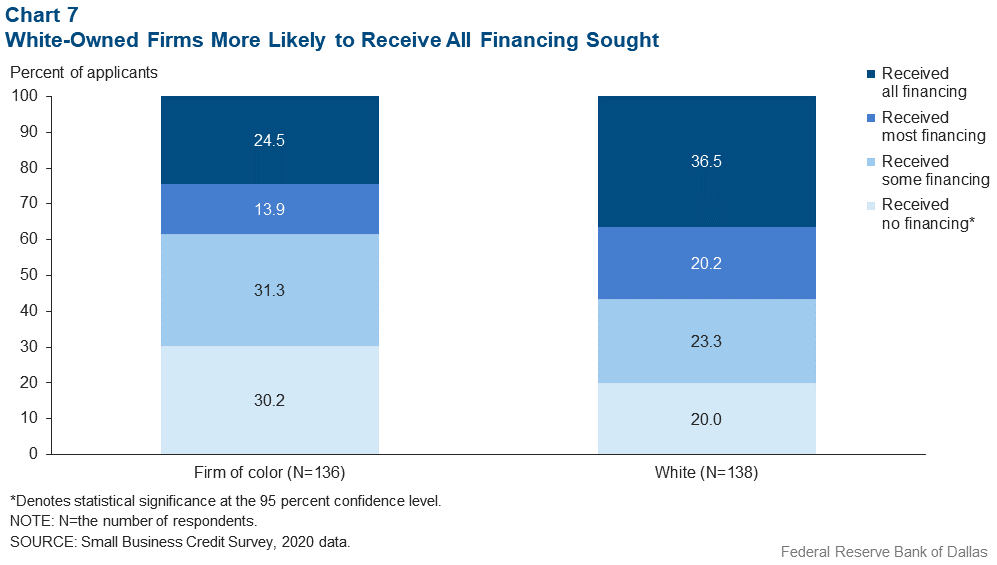

For those who did apply for nonemergency financing, most businesses received at least some of what they sought. However, while just 1 in 5 white-owned small businesses were unsuccessful in getting approved for any financing, almost a third of firms of color were not approved (Chart 7).

Finally, the SBCS asked firms what type of institution they currently use for their financial services (payments processing, loans, etc). While banks were the most popular across the board, firms of color were more likely than white-owned firms in Texas to report using credit unions and CDFIs.

Policy implications

One thing is clear from the data: Small businesses owned by people of color experienced more barriers in accessing funding in 2020, both emergency aid and nonemergency financing. These barriers pose a significant threat as the vulnerable firms that survived begin to emerge from the economic crisis. In fact, when asked to report their expected biggest challenge in the coming 12 months after the survey period last year, SBOCs cited weak consumer demand (32 percent) and limited credit access (24 percent)—larger than worries about government mandates, supply-chain disruptions and labor.

This analysis of information collected in 2020 is not simply a postmortem; it raises very real policy considerations and implications for program design moving forward. When we spoke at the roundtables with small businesses and the intermediaries that serve them, we also asked about best practices for designing programs that better reach underserved firms. Their recommendations include:

- Grants over loans: Some small firms are debt averse and/or overleveraged, making applying for additional loans unappealing. Thus, local governments and nonprofits reported more take-up of grant programs than loans. Participants suggested that, when possible, grants, or forgivable loans, are preferable to traditional lending.

- Tie funding to technical assistance or business improvements: Intermediary partners nearly universally remarked that a best practice is tying grant funding to training or technical assistance. One example is the El Paso County FASTER Forgivable Loan Program that tied funding to business coaching focused on COVID-19 safety. As explained by a CDFI representative, “If there were more programs set up like that [FASTER], that would be more helpful rather than a general grant. That would help get to these fundamental elements so people can move forward. There should be funding for a continuity plan. Or digital sales. Or a grant could pay for technical assistance services.”

- Promote through local, trusted networks: Establishing the legitimacy of grant and loan programs is easier when offered through networks that have preexisting relationships with underserved businesses. Promoting opportunities for funding through CDFIs, Minority Business Development Agencies, community banks, Small Business Development Centers and chambers of commerce can better reach vulnerable businesses.

- Allow applicants to apply for multiple rounds: Given that many of the grant or loan products created locally were not offered in large amounts, small business owners should not be penalized after receiving one. As one intermediary partner noted, just one grant is not enough to keep a small business alive. A best practice for grant initiatives that had multiple rounds of funding was to allow any applicant to participate in additional rounds, even if the firm had previously received financing from the same source or another one.

Perhaps there will be chances to enact some of these best practices in federal and state funding programs. Modified guidance was enacted when the PPP reopened in 2021, and several other federal programs are underway.

One is the SBA’s Community Navigator Pilot Program, which aims to better reach underserved small businesses through trusted, local intermediaries and connect them to relevant SBA programs and services. Recognizing some of the flaws in PPP outreach to the most vulnerable firms, the program has already awarded grants ranging from $1 million to $5 million to community organizations focused on aiding these businesses.

Also, the American Rescue Plan reauthorized a 2010 program, the State Small Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI), providing $10 billion in total, including an estimated $286.5 million to Texas. States will be given authority to design their own programs in the areas of small business finance or technical assistance. The SSBCI has a national $1.5 billion set-aside for “socially and economically disadvantaged businesses,” such as firms owned by women, people of color and veterans. States will apply for their funds in December 2021.

Optimism for the future

Despite the myriad challenges facing SBOCs, respondents expressed some degree of optimism for 2021 and beyond: 41 percent expected revenue to increase in the 12 months after the survey last year, while 17 percent anticipated no change. Additionally, almost a third expected to increase their payrolls, compared with less than a quarter who anticipated decreasing staff.

Resilience was a notable theme in our roundtables, where business owners described the creative business-model pivots and technology conversions that helped them survive 2020. More insights into the pandemic-period experiences of small businesses of color will be released in midyear 2022 after the 2021 Small Business Credit Survey results are rigorously analyzed.

Small businesses overall employ nearly half of the private sector labor force and contribute about 44 percent of private nonfarm gross domestic product, making them a critical part of the U.S. economy.[7] Small businesses of color already make up nearly a fifth of businesses nationally and more than a quarter of those in Texas. Given the demographic shifts at play in both the U.S. and Texas, closing disparities affecting small businesses of color is not just a moral concern, but an imperative for the long-term, postpandemic health of the economy.

About the survey

The Small Business Credit Survey (SBCS), a collaboration of all 12 Federal Reserve Banks, provides timely information about small business conditions to policymakers, service providers and lenders. In 2020, the survey reached more than 15,000 small businesses. About 9,700 of these were employers, or those with between one and 499 full-time or part-time staff. The sample size for Texas was 778 small employers.

The survey was fielded in September and October 2020, approximately six months into the pandemic. The data captured reflect experiences with government assistance such as the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), estimates of revenue losses since March 2020 and expectations of recovery going forward. At the time of the survey, the first round of PPP had closed, and a second round had not yet been announced.

The SBCS uses a convenience sample of establishments. Businesses are contacted by email through a diverse set of organizations that serve the small business community. To control for potential biases, the sample data are weighted so that the weighted distribution of firms in the SBCS matches the distribution of the small-firm population (one to 499 employees) in the United States by number of employees, age, industry, geographic location, gender of owner(s) and race or ethnicity of owner(s). In addition to the U.S. weight, state- and Federal Reserve District-specific weights are used.

For more information, please visit the Fed Small Business website.

Notes

- We define a small business of color as one that is at least 51 percent owned by a person who identifies as: Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Native American or Middle Eastern/North African. This report contains information about employer firms—small businesses that have between one and 499 employees beyond the business owner.

- The 2020 SBCS was fielded in September and October 2020, after the closing of the first round of PPP and before the launch of the second round.

- See “2021 Report on Firms Owned by People of Color,” Small Business Credit Survey, Federal Reserve, and “COVID-19’s Effect on Minority-Owned Small Businesses”; by Andre Dua, Deepa Mahajan, Ingrid Millan and Shelley Stewart, McKinsey and Co., May 27, 2020.

- Five roundtables were conducted between March and May of 2021. Four roundtables involved conversations with 44 small business owners, and one roundtable featured 17 small-business-serving intermediaries.

- Community Development Financial Institutions are financial institutions that are mission-driven, focused on serving low- and moderate-income communities. They typically finance small businesses, as well as nonprofits and affordable housing developments.

- This difference is not statistically significant at the 95 percent confidence level.

- “2019 Small Business Profile,” Office of Advocacy, Small Business Administration.

Author

The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.