A Report on the Texas Economy and a Hawk(s)eye View on Recent Fed Pronouncements: What Does It All Mean?

February 2, 2012 Austin, Texas

Thank you, Patti [Ohlendorf]. I am flattered that such a great group of Austinites has turned out tonight. I am especially pleased that Alejandro and Rosa Laura Junco are here.

Alejandro is CEO of the print media company Grupo Reforma. He has earned a sterling reputation for journalistic independence in a part of the world where independence is a rare and sometimes dangerous thing. Columbia University, the University of Missouri and Michigan State University have honored him for his journalistic accomplishments, and the University of Texas at Austin has named him a Distinguished Alumnus.

Alejandro’s company and its flagship paper in Mexico City take their name from La Reforma, a period of liberalizing reforms that transformed Mexico into a nation state in the mid-19th century, beginning with the overthrow of the man Texans know best and like least—Santa Anna—and ending with the ascension to power of a good general gone bad, Porfirio Diaz. As a child growing up in Mexico City, I was taught about La Reforma in school. To this day, I can probably tell you as much about Benito Juarez, journalist-turned-jurist-turned-president Jose Maria Iglesias and other Reformistas as I can about Houston or Lamar or Washington or Lincoln.[1] Alejandro and Rosa Laura, seeing you tonight has revived school-day memories of some 53 years ago! It is a delight and honor to be with you.

I will do two things tonight. First, I will give you an update on the performance of the Texas economy and what lies ahead. Second, I will give you my personal view of what the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee—the FOMC—announced after our meeting last week. Then, time permitting, I will be happy to avoid answering any questions you might have.

An Update on the Texas Economy

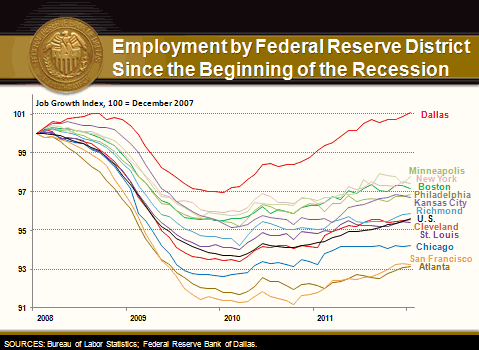

The economic performance of Texas since December 2007—the beginning of the U.S. recession, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research—can be summarized with the chart being projected on the screen denoting employment growth in the 12 Federal Reserve districts. The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas and its branches in Houston, San Antonio and El Paso administer the business of the Eleventh District (depicted by the red line), which includes Texas, northern Louisiana and southern New Mexico; 96 percent of the economic production of my district comes from the 25.7 million people of Texas. In 2011, Texas created 211,600 jobs. We now have more people at work than we had before we felt the effects of the Great Recession in the United States. We have now surpassed our previous peak employment levels.

Only two other states can claim they surpassed previous peak employment levels: Alaska and North Dakota. I do not wish to denigrate the good people of Alaska and North Dakota, but note that their combined population roughly equals that of Travis County.

Readers of this speech abroad—say, in New York—might think our growth last year came only from the burgeoning oil and gas patch. They would be right to describe it as burgeoning: 30,000 jobs were added in the oil and gas and related support sector last year, an increase of 15 percent. But other sectors outperformed oil and gas in the number of jobs created in Texas in 2011: 58,000 jobs were added in the professional and business services areas, nearly 46,000 in education and health services and over 41,000 in leisure and hospitality. All told, the private sector in Texas expanded by 266,400 jobs, while the public sector, driven primarily by fewer schoolteachers, contracted by 54,800 jobs. In sum, Texas payrolls grew 2 percent, significantly above the national rate of 1.3 percent.

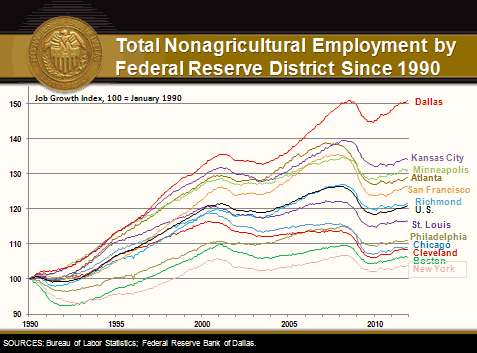

This performance is not unique to last year. As you can see from this second graph of employment growth by Federal Reserve district going back to January 1990, the Eleventh District has outperformed the nation on the job front for over two decades. Note the slope of the top line, which depicts job growth in the Eleventh District compared with all the rest and, importantly, relative to the black line—the seventh one down—the employment growth rate for the country as a whole.

Here is the point: Judging solely by the employment data, Texas went into recession seven months after the nation, in September 2008, and came out three months earlier, in December 2009.[2] We have now recovered fully from the Great Recession and are back on pace in leading the nation in job growth. Yes, we have a very large number of people earning minimum wage, a still-too-high unemployment rate of 7.8 percent and many other deficiencies, all of which were pointed out in high relief when a certain Texas governor was briefly in the hunt for his party’s nomination for the presidency. But I’ll bet you, those who love to point these things out and are given generally to Texas-bashing would give their right—or should I say, left—arms to have the record of job growth of the Eleventh Federal Reserve District that is documented by these charts. So good citizens of Austin and of Texas, you have much to be proud of.

As to projections, there is no reason to not expect continued job growth at the same pace in Texas. The budgetary constraints originally assumed for the state government have proven less severe than originally thought: Due to stronger-than-anticipated tax receipts, cutbacks in employment for schools and other state and local institutions may end up being less drastic. And if the Dallas Fed’s Texas Business Outlook Surveys for January, released this past Monday and Tuesday, are reviewed, job expansion looks promising and expectations regarding future business conditions are at the highest level in almost 12 months. Our most recent employment indexes in those surveys signaled an increase in both employment levels and in hours worked.[3] Thus, barring some unforeseeable shock, I would expect Texas to continue leading the nation in job creation.

An Inconvenient Truth

Incidentally, our record of job growth and the fact that people and companies have been voting with their feet and relocating to Texas from other states illustrate what for some is an inconvenient truth. The citizens of Texas and the Eleventh Federal Reserve District operate under the same monetary policy as do the rest of our fellow Americans. We have the same mortgage rates, pay the same rate of interest on commercial and consumer loans, and earn returns and borrow at the same interest rates as do our brethren in the rest of the country. Which raises an important question: If monetary policy is the same here as everywhere else in the United States, why does Texas outperform the rest?

The answer is no doubt complicated by the fact that we are blessed with a comparatively great amount of nature’s gifts, a high concentration of military installations and other “unfair” advantages. But one cannot avoid the conclusion that one of those “unfair” advantages is that we have a Legislature, based here in Austin, that under both Democrat and Republican governors has over time crafted laws and regulations that encourage business expansion and job creation. They have conducted the fiscal affairs of the state so as to maintain confidence in the future. One might draw two lessons here: first, that Germany’s finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, is right when he says, “If you want more private demand, you have to take people’s angst away” by having responsible and disciplined fiscal policy;[4] and second, that fiscal policy either complements monetary policy or retards its effectiveness as a propellant for job creation.

Herein lies the tale of the recent long-term policy and strategy statement issued by the FOMC at the conclusion of its meetings last week.

The Recent Pronouncements of the FOMC

Many of you may have read that the FOMC did three things after its two-day meeting Tuesday and Wednesday a week ago.

First, the committee issued the usual policy statement, stating that it “currently anticipates that economic conditions … are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate at least through late 2014.”[5]

There are presently 17 participants in FOMC meetings: the 12 Federal Reserve Bank presidents and the five current governors. Ten out of the 17 people get to vote in any given year, with the governors and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York always having a vote. I voted last year, and you may recall that together with Mr. [Charles] Plosser of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia and Mr. [Narayana] Kocherlakota of the Minneapolis Fed, I resisted the notion of a need for a statement indicating that monetary accommodation be tied to a specific date, be it in mid-2013, late 2014 or any other. Instead, I feel that the key should be to calibrate monetary policy according to the state or condition of the economy.

While most all of my colleagues value the state-contingent argument, at last week’s meeting the majority of this year’s voters felt that a combination of factors—including an expectation that “economic growth over coming quarters [will] be modest and … the unemployment rate will decline only gradually”; that the housing sector “remains depressed”; and that a “slowing in global growth” and other factors, combined with an anticipation “that over coming quarters, inflation will run at levels at or below those consistent with the Committee’s dual mandate”— warranted a need for the committee to indicate it would likely maintain a significantly accommodative monetary stance for another three years.

Second, the statement was accompanied by a first-ever release of the individual economic and interest-rate forecasts of all the policy meeting’s 17 participants. Mind you, these are not binding commitments. They are based on the assumption of “appropriate monetary policy” and are, despite the best of intentions, largely guesswork, especially looking out over a multiyear period.

My predecessor at the helm of the Dallas Fed, Bob McTeer, used to say, “The first rule of forecasting should be ‘don’t do it.’” The second rule, he would add is, “If you give a number, don’t give a date.” But given the assignment to venture a vision as to where the fed funds rate would be in each of the next three years and over “the longer run” to the nearest one-quarter of one percent, the 17 intrepid souls of the FOMC, including yours truly, did so. Only three envisioned that the fed funds rate might rise from current levels by year-end 2012; six saw it doing so by year-end 2013 and 11 by year-end 2014. Over the longer term, the 17 members envisioned a funds rate of between 3¾ and 4½ percent.

Bob McTeer’s admonishment clearly does not resonate with the FOMC. And yet I would caution, again, that at best, the economic forecasts and interest-rate projections of the FOMC are ultimately pure guesses. I have yet to find a single economist on this planet who consistently forecasts the economy accurately, let alone projects with any precision the interest rate on overnight funds one year out or far into the future. If you examine the record of the Blue Chip economists or even of our superb Federal Reserve staff, you will find confirmation of a paucity of reliable economic forecasts.

I note that even publicly traded companies that wrestle with the relatively easy task of providing forward guidance on revenue and earnings find that exercise especially vexing; most won’t venture beyond forecasting the upcoming quarter—and that is after they already have a month’s worth of the quarter’s data in hand! In this morning's Financial Times, Charles Goodhart, professor emeritus at the London School of Economics and former member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, claims to have examined the record of three central banks that have most prominently engaged in the practice of providing multiyear rate forecasts. He concludes: “The record for central banks in New Zealand, Sweden and Norway is not encouraging. In the short run, over the next three months and to a lesser extent over the subsequent quarter, these central banks do have additional (inside) information about their own future actions. Beyond this, however, the extra informational content of those central bank forecasts is zero. Moreover, the market knows that central bankers have no superhuman forecasting ability and will tend to view the supposed longer-term forecasts as a version of jawboning, attempts to persuade the market to change its mind for immediate policy purposes. Again, there is little empirical evidence that the market responds to such jawboning, and why should it when the central bank is as ignorant of the longer-term future as they are?”[6]

I don’t in any way consider my learned colleagues on the FOMC to be ignorant. But I draw upon my own experience in the corporate world and upon the insights offered by Goodhart to suggest that you simply take all this forward guidance and forecasting a year or more out with a big grain of salt, bearing in mind that the policy statements and forecasts issued by the FOMC are tactical judgments of the moment, made within a broader strategic context.

The Most Important Announcement

Which leads me to what I consider the third and most important announcement we made last week: the statement of our longer-range goals and strategy. For the first time, the entire 17-member committee stated that, given inflation over the longer term is primarily determined by monetary policy, we are able to specify that an inflation rate of 2 percent, as measured by the index for personal consumption expenditures, is most consistent with our mandate. At the same time, we stated that we cannot specify an exact goal for employment because “the maximum level of employment is largely determined by nonmonetary factors that affect the structure and dynamics of the labor market” and that “change over time and may not be directly measurable.”[7]

In the aviary of monetary policy makers, I am considered a “hawk.” I respect the fact that the Congress of the United States has given the Federal Reserve a dual mandate of conducting monetary policy so as to have full employment and simultaneously maintain stable prices. I believe monetary policy is the principal determinant of long-term price stability. But I have long maintained that monetary policy is but one gear in the complicated gearbox that drives job creation. Education and other structural aspects of our economy condition the nation’s job-creating capacity; fiscal and regulatory policy, in turn, condition both the structure and dynamics of employment. I was delighted that the full committee recognized this and made it part of its official credo.

In a world driven by rapid technological change and globalization, job-creating capital will flow not only to countries that conduct sound monetary policy but to places with the most welcoming, competitive tax and regulatory systems. This was underscored in a recent Harvard Business School (HBS) survey authored by Jan Rivkin and Michael Porter, two widely admired scholars on national competitiveness and economic development. Their survey of HBS alumni found that the greatest impediments to investing in and creating jobs in the U.S. are our current tax code and regulatory burden and uncertainty, as well as lagging workforce skills. Absent changes on these fronts, the Rivkin/Porter study found that more than 70 percent of respondents expect U.S. competitiveness to decline over the next three years, and along with it, job-creating investment.[8]

Thus for me, explicitly acknowledging that monetary policy’s impact on employment is transitory and uncertain is a cardinal event. It signals to the markets that there are limits to the ultimate job-stoking efficacy of Federal Reserve policy. To the extent that inflation is running below 2 percent, the Federal Reserve may have somewhat greater latitude to pursue accommodation. However, the past few years have demonstrated, yet again, that allowing inflation to rise by no means guarantees faster job growth. The message to our nation’s fiscal authorities is that they cannot expect monetary policy to substitute for the need to get their act together, stop their shameful politicking, get on with putting their fiscal and regulatory house in order and do so in a manner that encourages rather than continually undermines job creation and economic expansion.

Fiscal Matters Matter

I noted how Texas has managed under the same monetary policy regime to more quickly return to peak employment than other states. I attributed this in significant part to prudent fiscal and regulatory policy, underscoring that this not only facilitates job and overall economic expansion in Texas, but is the underpinning of confidence. I would suggest that now is the time for prudent fiscal policy to be enacted by a Congress that on both sides of the aisle has for far too long, under both Republican and Democratic presidents, been shamefully negligent of its responsibility. Today marks the 1,009th day without an agreed-upon federal government budget. The Congress has found it easier to not agree on a budget than to go about correcting fiscal imbalances that drive the nation’s growing indebtedness. Our political leaders’ misfeasance exacerbates the “angst” that inhibits the confidence of consumers and job-creating businesses.

My staff has found a wonderful sketch on YouTube that might best illustrate the behavior of Congress. Here it is: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Li0no7O9zmE.

That sketch says it all. The Fed, the nation’s monetary authority, has clearly articulated its longer-run goal and policy strategy and has conducted itself with integrity by responding to the needs of the economy. In contrast, the fiscal authorities have conducted themselves with impunity: Their only long-term strategy is to pass the bill to our children and grandchildren.

Reforma Is Needed

I would suggest that Reforma is urgently needed in the conduct of fiscal affairs in our nation’s capital.

And I will leave you with this thought: The power to make that happen is in your hands. You and your fellow citizens across this great country are the ones who elect the people who tax you and decide where to spend your money; you ultimately direct the nation’s fiscal future.

And you share in the blame for it being such a mess.

Accepting the status quo means you are acquiescing to encumbering your children and your children’s children with mismanaged fiscal policy, crippling debt and a dismal economic future.

Look to Alejandro Junco as an example. He has taken great risk with his person and his family’s treasure to take on the status quo. Like Alejandro did for journalism in Mexico, I hope you will step up to the plate, risk whatever personal benefits and comforts you derive from the current regime and use your talents and resources to force a course correction in the fiscal affairs of our nation. For only then can we be assured of a bright and prosperous economic future. And only then can monetary policy, properly conducted, perform with maximum efficiency and minimal risk to price stability to restore the great job-creation potential of America.

Thank you.

Notes

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve System.

- For non-Texans, Sam Houston was the first and third president of the Republic of Texas (1836–38 and 1841–44); Mirabeau B. Lamar was the second president of the Republic of Texas (1838–41).

- According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the nation went into recession in December 2007 and came out in June 2009. According to the Dallas Fed’s Texas Index of Coincident Indicators, Texas went into the recession in August 2008 and came out in December 2009.

- “Q&A: German Finance Minister Takes On Critics,” by Marcus Walker, William Boston and Andreas Kissler, Wall Street Journal, Jan. 29, 2012.

- See the FOMC’s statement, Jan. 25, 2012, www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20120125a.htm.

- “Longer-term Central Bank Forecasts Are Step Backwards,” by Charles Goodhart, Financial Times, Feb. 2, 2012.

- See the FOMC’s statement, Jan. 25, 2012, www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20120125c.htm.

- “Prosperity at Risk: Findings of Harvard Business School’s Survey on U.S. Competitiveness,” by Michael E. Porter and Jan W. Rivkin, Harvard University, January 2012.

About the Author

Richard W. Fisher served as president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas from April 2005 until his retirement in March 2015.