The Limits of the Powers of Central Banks (With Metaphoric References to Edvard Munch's Scream and Sir Henry Raeburn's The Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch)

June 5, 2012 St. Andrews, Scotland

Thank you, Professor Sutherland. I am delighted to be here at St. Andrews and very much appreciate your organization of this meeting today. To be at the site where John Knox preached an epic sermon about Christ’s cleansing of the temple and overthrowing the money changers’ tables, which was so powerful that it led to riots against the establishment of the time, the papacy, is daunting—nearly as much so as playing the Old Course on yesterday’s bank holiday with Professor Andy Mackenzie, the university’s great scratch golfer and noted physics professor.

In a setting as august as this one—on the eve of the 600th anniversary of this great academy—and speaking on the day marking the 129th anniversary of the birth of John Maynard Keynes and the 289th anniversary of the baptism of Adam Smith in nearby Kirkcaldy—I should disclose up front that I am the least formally trained among the mostly academic economists who sit at the table where we make monetary policy at the Federal Reserve, the 19-person forum known as the Federal Open Market Committee, or FOMC. I have an MBA, not a PhD. I am an autodidact when it comes to monetary theory. On the other hand, I am the only participant in our policy deliberations who has been both a banker and a professional money manager—the only one who has been a market operator. What the credentialing gods denied me, the practitioner angels kindly granted me: another skill set that provides a complementary perspective to those of my more learned colleagues. I shall speak today, as I always do, only from my perspective; nothing I say represents the thinking or proclivities of other members of the FOMC. And most of what I will say will confront theory with my interpretation of the rude reality of the marketplace.

A Quick Primer on the Federal Reserve’s Structure

For those of you who do not know well our central bank’s structure, a quick primer. The Federal Reserve is the third central bank in American history. We were created during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency, in the aftermath of the Financial Panic of 1907. Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act in 1913; like St. Andrews, we will mark a centennial next year, but it will be our first, while you celebrate your sixth.

The Federal Reserve Act established 12 Federal Reserve Banks, together with a Board of Governors. The members of the Board, of which Ben Bernanke is Chairman, are appointed by the president of the United States and confirmed by the Senate. The 12 Bank presidents are not: They serve at the pleasure of nine-member boards of directors composed of private bankers and citizens from their respective districts. They are distinctly nonpolitical, immune from partisan influence; they represent Main Street, not the Washington power elite or the New York money changers, just as President Wilson and the Federal Reserve founders envisioned. These are profit-making banks that perform services for the private banks in their districts: warehousing and distributing currency; operating discount windows from which banks borrow to assist in their operating funding needs; functioning as the depository for the $1.5 trillion or so in excess reserves presently piled up and going unused in our private banking system. The Banks also house and manage staff that supervise and regulate banks in the districts (under policy guidance from the Board of Governors), and perform other services, the most widely observed and commented upon of which is the operating of the open-market operations conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York on behalf of all 12 Banks at the instruction of the FOMC. All 12 Bank presidents serve on the FOMC together with the seven members of the Board of Governors. This is where monetary policy for the United States is determined by collective decision. The operating procedure of the FOMC is for each of the governors to have a vote on policy; the bankers rotate their votes, with the New York Fed having a constant vote. However, all 19 members—the seven governors and the 12 bankers—participate fully in every FOMC meeting and actively contribute to policy discussions.

The FOMC has traditionally decided the federal funds rate, the overnight rate for interbank lending that anchors the yield curve. In recent years, in reaction to the Financial Panic of 2008 and 2009 and its aftermath, the FOMC has instructed the New York desk to buy mortgage-backed securities and Treasury notes and bonds—eschewing Treasury bills. Presently, the Fed holds more than $850 billion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and over $1.6 trillion in Treasuries. This expansion of our portfolio and extension of maturities held therein is known as “quantitative easing,” or QE. After cutting the base rate for overnight lending—the fed funds rate—to zero, the majority of the committee decided to expand the money supply by purchasing MBS, notes and bonds. When we buy something in the marketplace, we pay for it, and this has resulted in significant liquidity floating about the U.S. economy, much of it going unused. As mentioned earlier, $1.5 trillion of excess reserves from private banks is on deposit in the 12 Federal Reserve Banks, where it earns a paltry 0.25 percent, rather than being lent to job-creating businesses at rates bankers would prefer. Additionally, some $2 trillion of excess cash is parked on corporate balance sheets—above and beyond the operating cash flow needs of the business sector—and copious amounts of cash are lying fallow in the pockets of nondepository financial institutions, such as private equity and other investment funds.

A running discussion in the marketplace centers around whether the FOMC will decide to engage in further quantitative easing, especially given the most recent economic weakness in the U.S., against the backdrop of the well-known problems in Europe and slower growth in China and other “emerging” economies. I shall turn to that in a few moments. First, I want to go back to the 12 Federal Reserve Banks.

Different Growth Patterns in the 12 Federal Reserve Districts

Here is a map of the 12 Federal Reserve Bank districts. The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas is responsible for the Fed’s activity in the light green area—the Eleventh District—home to 27 million people in Texas, northern Louisiana and southern New Mexico. Roughly 96 percent of the district’s output comes from Texas.

Here is a chart showing the disparate behavior of the economies in the 12 Federal Reserve Districts, as measured by employment growth. You will see that going back to 1990—some 22 years—the Eleventh Federal Reserve District has outperformed the other Federal Reserve Districts in job creation.

In terms of employment, the Dallas Fed’s district went into the recession last and was one of the first to come out. We have since punched through previous peak employment levels.

Here is the job creation record of the so-called mega-states within the United States since 1990. And last, and just for fun, here is the record of Texas’ job creation over the past two decades versus resource-rich countries, such as Australia and Canada, as well as versus the major countries of Europe, the U.S. and Japan.

Indulge me for a minute here. I share these with you not to engage in stereotypical “Texas brag” or because St. Andrews has become a popular destination for recent generations of undergraduate scholars from Texas. I do so to illustrate a point, specifically the influence of fiscal policy on the effectiveness of monetary policy.

The Limits of Monetary Policy and the Importance of Fiscal Policy

Here is the rub. As mentioned, the FOMC sets monetary policy for the nation, for all 50 states—its influence is uniform across America. The same rate of interest is charged on bank loans to businesses and individuals in Texas as is charged New Yorkers or the good people of Illinois or Californians; Texans pay the same rates on mortgages and so on. Why is it that the Texas economy has radically outperformed the rest of the states? A cheap answer is to revert to the hackneyed argument that Texas has oil and gas. It is true that we produce as much oil as Norway and almost as much natural gas as Canada. And we have some 60 percent of the refineries of the United States. But remember that the numbers I showed you are employment numbers. Only 2 percent of employment in Texas is directly generated by oil and gas and mining and related services. We are grateful that we are energy rich. But we are a diversified economy not unlike the United States, where business and financial services, health care, travel and leisure activities and education account for similar portions of our workforce. Why, then, do we outperform the rest of the United States?

To me, the answer is obvious: We have state and local governments whose tax, spending and regulatory policies are oriented toward job creation. We have the same monetary policy as all the rest; our income is taxed at the same federal tax rate; and we are equally impacted by Washington’s tax, spending and regulatory policies. But we have better fiscal policy at the state level. We have no state income tax; we are a right-to-work state; we have state and local governments that, under both Democratic and Republican leadership, have for decades assiduously courted job creators—so much so that we have even outperformed the job creation of most every other major industrialized economy worldwide, as shown by the previous slide.

Whither Monetary Policy?

Now, back to the hue and cry of financial markets, and the question of further monetary accommodation. Interest rates are at record lows. Trillions of dollars are sitting on the sidelines, not being used for job creation. We know that in areas of the country where fiscal and regulatory policy incents businesses to expand—Texas is the most prominent of those places—easy money is more likely to be put to work than in places where government policy retards job creation. During the next few weeks as I contemplate the future course of monetary policy, I will be asking myself what good would it do to buy more mortgage-backed securities or more Treasuries when we have so much money sitting on the sidelines and yet have no sense of direction for the future of the federal government’s tax and spending policy. And with the president’s health care legislation awaiting resolution in the Supreme Court, we also know that no business can budget its personnel costs until that case is decided. If job-creating businesses have no idea what their taxes will be, are clueless about how federal spending will impact their customers or their own businesses and cannot budget personnel costs—all on top of concerns about the risk to final demand posed by the imbroglio in Europe and slowing growth in emerging-market countries—how could additional monetary policy be stimulative?

A good theoretical macroeconomist can acknowledge that a great deal of liquidity is, indeed, going unused at present. They might likely argue that further monetary accommodation would raise inflationary expectations by magnifying the fear that the Fed and other monetary authorities are hell-bent on expanding their balance sheets and, consequently, the money supply so dramatically that inflation will inevitably follow. The result, the good macroeconomist would deduce, would be salutary: It would scare money out of businesses’ pockets and into job expansion and would lead individuals to conclude they better spend their money today rather than have it depreciated by inflation tomorrow, thus pumping up consumption and final demand.

I beg to differ. I would argue that this would represent a form of piling on the already enormous uncertainty and angst that businesses face with our reckless fiscal policy. To me, that would be the road to perdition for the Federal Reserve. There is in the marketplace a lingering fear that the Fed has already expanded its balance sheet to its stretching point and that an exit strategy, though articulated, remains theoretical and untested in practice. And there is a growing sense that we are unwittingly, or worse, deliberately, monetizing the wayward ways of Congress. I believe that were we to go down the path to further accommodation at this juncture, we would not simply be pushing on a string but would be viewed as an accomplice to the mischief that has become synonymous with Washington.

Raeburn versus Munch

There is no question that these are worrisome times: The world economy is slowing, joblessness is rampant in many countries, and in the United States, growth is anemic and unemployment remains unacceptably high. To me, this means that the Fed, and all central banks, must keep their heads about them and not give in to the convenient recommendations of those who are given to solving all problems with monetary policy.

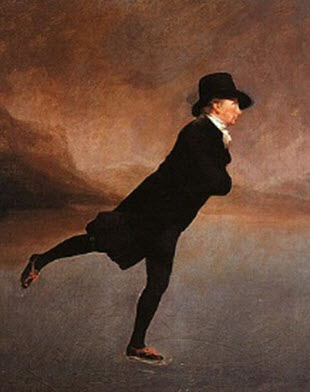

If only for your visual pleasure, I have chosen two paintings anybody in the vicinity of St. Andrews and Edinburgh would know, in order to illustrate alternative approaches to central banking at this juncture.

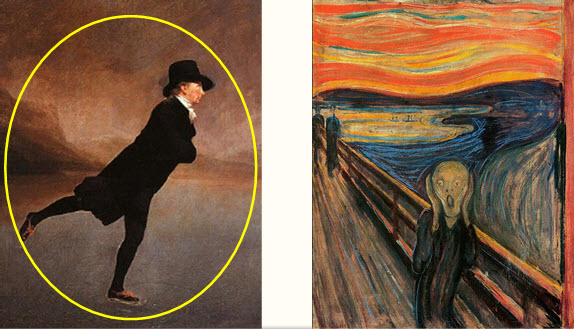

The first is an icon of Scottish culture: Sir Henry Raeburn’s depiction of The Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch, a seminal work in the permanent collection of the Scottish National Gallery and a favorite of mine since I first saw it some 30 years ago.

To me, Raeburn’s work provides a fitting visual metaphor for the ideal countenance of a central banker: The Reverend Walker skating forward confidently and with grace upon a notably uneven, rocky surface on an icy, dark, blustery day.

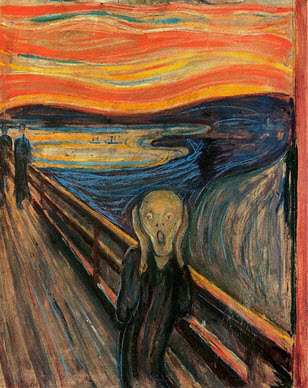

An alternative depiction is Edvard Munch’s The Scream from Norway’s Gunderson Collection, now on temporary exhibit at the National Gallery. (There are four versions of this pastel, one of which recently sold for $119.9 million at auction at Sotheby’s. If you haven’t been into Edinburgh to see the Gunderson version, I am sure you read about Sotheby’s record-setting auction.)

In sharp contrast to Raeburn’s painting of composure, The Scream depicts a panicked form. In an autobiographical epigraph, Munch wrote that he conceived of the painting after a period of exhaustion and despair: “I stopped and leaned against the balustrade, almost dead with fatigue. Above the blue-black fjord hung the clouds, red as blood and tongues of fire. My friends had left me, and alone, trembling with anguish, I became aware of the vast, infinite cry of nature.”[1]

I am going to conclude by suggesting that the image that best behooves central bankers as guardians of financial stability and agents of economic potential is that of Henry Raeburn’s Reverend Walker. To be sure, central bankers everywhere are fatigued and exhausted and increasingly friendless. But when the landscape is dark and threatening, those charged with making monetary policy must comport themselves with a grace that reassures markets and the public that they are calmly in control of the sacred charge with which they have been entrusted. They must keep their “cool” even when the vast, infinite cry of the money changers reaches a fevered pitch, the economic seas are blue-black and the clouds in the financial markets are red as blood and tongues of fire. Presenting an image comparable to that of the visage depicted by Edvard Munch—of policymakers trembling with anguish at the daunting demands of their profession—would provide scant comfort to those who depend upon them to maintain their composure and skate ably across a cold and foreboding economic landscape, seeking to guide the economy to a better place.

Central banks are just one vehicle for influencing overall macroeconomic behavior, in addition to influencing through regulation the microeconomic agents that transmit that influence to the markets—banks of deposit and other financial institutions. We work alongside another potent macroeconomic lever: fiscal authorities—governments that have the power to tax the people’s money, spend it in ways they deem appropriate, and create laws and regulations that influence microeconomic behavior.

Unless fiscal authorities can structure their affairs to incent the private sector into putting the cheap and ample money the Fed has provided to the economy to work in job creation, monetary policy will prove impotent. And we will likely barely survive our first centennial, let alone have confidence that we will reach our sixth.

Thank you.

Notes

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve System.

- “Painting and Sculpture in Europe 1880 to 1940,” by George Heard Hamilton, Baltimore, Md.: Penguin Books, 1967, p. 75. This quote was written by Edvard Munch in his epigraph for the “The Scream”—known then as “The Cry”—when it was reproduced in the Revue blanche in 1895.

About the Author

Richard W. Fisher served as president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas from April 2005 until his retirement in March 2015.