Suggestions After a Decade at the Fed

February 11, 2015 New York City ·

I am grateful to be invited to speak to the Economic Club of New York on the eve of my retirement from 10 years of service as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. I have sat through 78 regular meetings and an additional 18 special meetings of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) for a total of 96 meetings under three Fed Chairs over the past decade. Given what we went through during the crisis and the healing we have tried to engineer in its aftermath, I would argue you ought to measure the life of a Fed policymaker in dog years. This morning, I thought I might offer some suggestions based upon those 70 years of experience.

Roosa Boys

Before doing so, let me say I am tremendously honored to be introduced by Paul Volcker. Paul and I share a common heritage: We were both mentored by the late, great Robert V. Roosa. We are two of the “Roosa Boys,” the men—and women—Bob Roosa took under his wing every few years to teach real-world economics and a love for policy. Paul was “Class of ’47” in the Roosa “school”; I was ’75. Of course, none of the successive Roosa Boys (and Girls) could ever match the original standard, as is sometimes said about our nation’s presidency. I consider Paul to be the George Washington of monetary policy—the very exemplar of the leadership and integrity and dedication that needs to be the inviolable hallmark of every central banker who follows in his footsteps.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, prudent monetary policy gave way to political expedience before the quick-and-easy approach was reined in by Paul. Were it not for his insistence that the Fed do what was politically unpopular, we would have seen our nation and the world destroyed by hyperinflation. Please join me in applauding Paul for his selfless service to our great country.

Hogwarts, the Death Star and Ebenezer Scrooge

Paul Volcker stood his ground on the principle that monetary policy should never be politicized. Which brings me to the first message I wish to impart today: that of the overriding importance of maintaining an independent Fed.

I recently came across a little volume by John Lanchester, titled How to Speak Money. In describing the Bank of England, Lanchester writes: “There’s a lot of ritual and ceremony and protocol at the Bank, which to outsiders seems a cross between Hogwarts, the Death Star, and the office of Ebenezer Scrooge.”[1] The same can be said of the Federal Reserve, at least by those who don’t take the time to read the copious amounts of reports and speeches and explanations the 12 Federal Reserve Banks and the Board of Governors continuously emit. It is always politically convenient to make something sound mysterious, if not malevolent, by claiming it is opaque.

Which is precisely what is happening now with Senate Bill 264: the Federal Reserve Transparency Act of 2015 and its call to “audit the Fed.” The operations and finances of the Board of Governors and the 12 Federal Reserve banks are already audited up the wazoo. As to policy, as soon as our deliberations at the FOMC conclude, we report to the public what we decided. We publish a thorough review of what we discussed—and all views are considered, even those of dissenters like Richard Fisher—in the form of minutes of every FOMC meeting three weeks after we meet. And we subject our Chair to a no-holds-barred press conference on a quarterly basis. All of this alongside frequent speeches and press interviews by the 12 Federal Reserve Bank presidents, who voice their independent views.

My suspicion is that many of those in Congress calling for “auditing” the Fed are really sheep in wolves’ clothing. Having proven themselves unable to cobble together with colleagues a working fiscal policy or to construct a regulatory regime that incentivizes rather than discourages investment and job creation—in other words, failed at their own job—they simply find it convenient to create a bogeyman out of an entity that does its job efficiently.

I come from Texas. I hail from the land of Wright Patman and Henry B. Gonzalez. I am fully aware of the appeal of Fed antipathy and the passion it can stir. It is nothing new. Close your eyes when you hear a strident speech about auditing the Fed from one of the current bill’s authors and you will hear echoes of radio broadcasts from the 1930s of Father Charles Coughlin, pastor of the Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, Mich. He railed passionately against the “money changers” and what he termed “the Federal Reserve banksters … and the rest of that undeserving group who without either the blood of patriotism or of Christianity flowing in their veins have shackled the lives of men and of nations ...”[2] That’s powerful rhetoric.

I am personally confident that responsible senior senators and congressmen like Sen. (Richard C.) Shelby of Alabama, who chairs the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, and Congressman (Jeb) Hensarling, the Texan who chairs the House Financial Services Committee, can prevent any meddling with monetary policy while understanding the need for their colleagues to vent and score political points. And I find it hard to believe that wise and experienced leaders like Sen. Mitch McConnell would actually want the Fed’s policy deliberations to be infected by politics. There is so much else to do under the purview of the Senate and the Congress to clean up the flotsam of fiscal policy and jetsam of regulatory interference that is inhibiting job creation and economic expansion.

But we’ll see. Mae West put it best: “I generally avoid temptation unless I can’t resist it.” Even the greatest political leaders have trouble resisting the temptation to fiddle with a central bank. If you read Liaquat Ahamed’s brilliant book, Lords of Finance, you’ll recall that German Chancellor Bismarck’s closest confidant, Gershon Bleichröder, warned him “… that there would be occasions when political considerations would have to override purely economic judgments and at such times too [politically] independent a central bank would be a nuisance.”[3] We know that when the German central bank gave into political considerations, the result was the Weimar hyperinflation and its eventual consequences. And that the Bank deutscher Länder, having established the principle of the independent central bank, which became the Bundesbank, was instrumental in Germany’s rising from the ashes of World War II and becoming the economic pillar of Europe.

Who in this room isn’t grateful that Paul Volcker was a nuisance?

“Audit the Fed” is nothing more than an attempt to override purely economic judgments and bend monetary policy to the will of politicians. It is misguided. I pray we don’t go there. I can think of nothing that would do more damage to our nation’s prosperity.

Worms in Whiskey

That doesn’t mean we should be deaf to the drumbeat of concerns about the Fed.

My friend, former Sen. Sam Nunn, likes to tell the tale of a backwoods preacher who was alarmed at the drinking habits of one of his parishioners. So the preacher called the man in. He put two glasses in front of him, one filled with water and the other with whiskey. He then put a worm in the glass of water. It swam around merrily. He then lifted the worm and placed it into the whiskey-filled glass. It sank to the bottom, dead. “Son, do you get the message?” the preacher asked. “Yes sir, I do,” the parishioner replied. “If I drink whiskey, I won’t get worms.”

Like the parishioner, I don’t think the Fed is getting the message.

First, in this era of social media and über-transparency, we at the Fed need to learn to speak English, rather than “Fedspeak.” I have done my level best during my tenure at the Fed to speak plainly, always bearing in mind that when I speak as a Fed official, I am speaking to the American people whom we serve, not to a small group of economists or just to the mavens of Wall Street.

The best case of this I have experienced the past decade occurred in May 2012, when the Dallas Fed board of directors traveled to a joint meeting with the board of the St. Louis Fed. The chairman of my board at the time was Herb Kelleher, the puckish, iconic founder of Southwest Airlines. Of course, we flew to St. Louis on Southwest. True to form, after we reached cruising altitude, Herb took the microphone and said: “My name is Herb Kelleher, and I want to thank you for flying on the airline I founded.” Herb is beloved by the people who fly Southwest; enthusiastic cheers and applause erupted from the passengers. Then he said, “Since I have a captive audience, I want to tell you about the Federal Reserve. Today, you have on board one of the most important people in the global financial system … me! Well, not really me, but I am chairman of the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, and with me is the Bank’s president, who sits on the committee that decides the amount and the cost of your money.” He went on to explain what the FOMC does and what the Fed banks do, how they are structured and so on, punctuating his remarks with references to Wild Turkey Bourbon and other personal favorites.

You know the kind of folks who fly Southwest. They range from people dressed like you and me in suits and ties to work-by-the-sweat-of-your-brow folk dressed in bib overalls—like the one seated behind me with his wife. When Herb finished, again to a big round of applause and attaboys, the man behind me turned to his wife and said, “Ethel, if Herb Kelleher is involved with the Federal Reserve, why did we vote for Ron Paul?”

Tie Your Camel

Second, I think we at the Fed must fully and frontally address the concern of many who feel that too much power is concentrated in the New York Fed. I am a great admirer of Bill Dudley. I consider him a dear friend and a man of tremendous capacity both as a policymaker and as a regulator of the financial institutions in his district. And I have enormous respect for Simon Potter and the good women and men who work our trading desk, faithfully implementing the instructions they receive from the FOMC, which crafts the nation’s monetary policy. Yet I understand the suspicions that surround the New York Fed.

There is an ancient Arab saying that one should “trust in Allah but tie your camel.” I would suggest the following common-sense proposals for quelling concerns for securing our franchise as an independent Fed and, in fact, creating a more efficient policymaking and implementing process. Bill, you might not like these, but I think they are needed:

1) We should rotate the vice chairmanship of the FOMC. Under the current structure, the president of the New York Fed is the FOMC’s permanent vice chair, which renders him the second-most-powerful person at the table, behind the Chair. The purpose of the FOMC is to decide policy and to instruct the New York trading desk to implement it by managing the Fed’s System Open Market Account and short-term trading operations. Having the New York Fed president as the FOMC’s vice chair gives the appearance of a conflict of interest. To correct this, I would rotate that position every two years to one of the other 11 Fed presidents.

We have a convenient mechanism for doing so: The 12 Fed presidents meet frequently to discuss operational matters under the Conference of Presidents. Remember, there are no operating entities at the Board of Governors in Washington; it is the 12 Banks that lend money through their discount windows, house the forces that examine banks, operate the vaults that keep safe the people’s cash, and so on. The Conference of Presidents rotates its chair among the presidents on a biennial basis. So I would simply have the chairman of the Conference of Presidents automatically become vice chair of the FOMC. This way, over the course of two years, the Federal Reserve representatives of all 50 states (and all congressional districts) would occupy the second-most-important slot on the FOMC, and any appearance of conflicted interest would disappear.

2) With regard to regulation, the greatest concern appears to be the problem of regulatory capture by the largest and most powerful institutions, the so-called Systemically Important Financial Institutions, or SIFIs. We have instituted at the Board of Governors a powerful and, to my mind, extremely able and disciplined leader on regulatory matters, Governor Dan Tarullo. But if that alone proves unsatisfactory to the Congress, a simple solution would be to have each of the SIFIs supervised and regulated by Federal Reserve Bank staff from a district other than the one in which the SIFI is headquartered. Each of the Fed Banks has an able body of examiners. With a tough central disciplinary authority in Washington dispatching those troops to districts where SIFIs are concentrated, we might eliminate any perception of conflicted interest and, again, assure that regulators from all 12 Federal Reserve districts, rather than from just two cities, are deployed in maintaining the safety and soundness of our banking system.

Those are the two suggestions I thought would be most offensive to this New York audience!

And I have a third and fourth:

3) I would give the Federal Reserve Bank presidents an equal number of votes as the Washington-based governors, save the Chair.

Presently, the New York Fed gets a permanent vote and the remaining 11 Banks get four votes, with Cleveland and Chicago voting every two years and the rest voting every three years. This makes no sense to me. The population of the New York Federal Reserve district is smaller than that of the San Francisco, Atlanta, Chicago, Richmond and Dallas districts. The Cleveland district is much smaller than New York’s, roughly equal to that of Kansas City, and only slightly larger than that of St. Louis, Boston and Philadelphia—each of which has 6 percent or less of the country’s population. (Minneapolis is the smallest district, with fewer than 3 percent of the nation’s population and roughly 1 percent of the Federal Reserve’s deposits.)

And if you look at population growth, it is clear that the districts that get to vote most often are not the ones that are growing but the regions that were most prominent generations ago. Since 1970, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland’s district has grown in population by less than 7 percent, New York’s by 9 percent and Chicago’s by 18 percent. At the other end of the spectrum, the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas’ district has grown by 123 percent, San Francisco’s by 112 percent, Atlanta’s by 105 percent and Richmond’s by almost 70 percent.

The current voting schedule makes no sense to me. But I wouldn’t necessarily change it simply to avenge the past. I would change it to balance out the division of power between the Federal Reserve Banks that are out in the field and among the people and businesses that operate our economy and have their own independent research staffs, and the Board of Governors, which is Beltway bound geographically and is briefed and guided by a single staff. I have great admiration for the brilliance and integrity of the members of the Board of Governors research staff. But you will notice that for at least a couple of decades, the governors have tended to vote in a block, and it brings to mind Peter Weir’s romantic comedy Green Card, where the character played by Gerard Depardieu chastises the woman played by Andie MacDowell, saying, “You get all your opinions from the same place.” The members of the Board get their opinions from the same staff; the Fed bankers who sit at the FOMC table get theirs from 12 disparate staffs of the same high quality as that which resides in Washington.

I would give six Banks the vote to match the six governors other than the Chair. The next year, the other six would have the vote. The Chair would then be the tiebreaker if a tie were to ensue, though given the collegial way in which we conduct our deliberations, my guess is that a tiebreaker would be a rarity. Thus, over a two-year stretch, all 50 states and all congressional districts would have someone representing their constituents sitting as a voter at the table. Every year, six Fed Banks whose presidents serve under boards of directors chosen from within the states in their districts would match wits with Fed governors appointed by presidents and approved by Congress, providing a balance between what some might consider representatives of Main Street and Washington factotums. To me, this is eminently sensible.

4) Fourth and finally, I would have the Chair hold a press conference after every FOMC meeting. I have long advocated this. Presently, the Chair holds a press conference every quarter. In effect, this means that any change in monetary policy can be made only at a quarter’s end. (For if we were to suddenly announce that in between quarter ‘X’ and quarter ‘Y’ the Chair was going to hold a press conference, it might spook and destabilize the markets). In the parlance of economics, this injects some time-dependency into our deliberations when we should be guided in making policy strictly by the state of the economy, and take action on monetary policy when it is needed. I believe the Chair should hold a press conference after every meeting to explain the whys and wherefores of the policy decision taken by the committee. This would both add transparency and give the FOMC greater leeway in implementing policy. For the record, I have been arguing for this for years now.

Monetary Alzheimer’s

In the interest of time, I am going to make some additional, abbreviated suggestions, based on my decade at the Fed.

Policymakers must be rigorous in their analysis but must be guided by common sense. We have developed very sophisticated models of the economy at the Fed, and they are useful in providing a framework for deliberation. Yet they are always at risk of becoming stale or inappropriate to the situation. My advice is to heed Charles Kindleberger’s warning that “different circumstances call for different prescriptions.” “The art of economics,” he said, “is to choose the right model for the given problem, and to abandon it when the problem changes shape.”[4]

Right now, we are trying to understand the dynamics of inflation. We have declared a 2 percent intermediate target for inflation, which seems to be standard for most central banks. Headline inflation measures show a significant shortfall from that target. The headline personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index fell 0.2 percent in December. Its 12-month increase was 0.75 percent, down from 1.6 percent in June. Should this low, and still falling, rate of price inflation retard the date of the liftoff from the zero-interest-rate policy we have been operating for more than six years?

I think not. We all know that headline inflation is being held down by the big decline in energy prices that began in the second half of 2014. We know that once energy prices stabilize, headline inflation is likely to bounce right back up. Policy needs to take past inflation into account, but it needs to take future inflation into account, too. That’s just another way of saying that, for policy purposes, it’s inflation’s medium-term trend that matters—which is why analysts and policymakers pay so much attention to core inflation measures. The widely heralded FRB/US model that has been used by the Board of Governors staff since 1996 is an example: It is built around PCE inflation excluding food and energy—which is the traditional measure of core inflation. Ex-food-and-energy PCE inflation was essentially zero in December, month over month, while the 12-month rate slipped to 1.3 percent from 1.5 percent in June.

Here’s where that Kindleberger quote is relevant. A good core inflation measure strips the noise out of headline inflation and leaves the signal. By that standard, recent analysis shows that the ex-food-and-energy PCE inflation rate that drives the FRB/US inflation forecast is a second-rate core inflation measure, at best. An alternative measure developed at the Dallas Fed—the Trimmed Mean PCE—is superior in three respects.

First, trimmed mean inflation is better insulated from transitory energy-price swings. Since 1994 (the start of the current 2 percent-inflation era), conventional core inflation’s correlation with changes in the real price of oil is 0.26, while trimmed mean inflation’s correlation is just 0.05.

Second, as judged by root-mean-square error (sorry, but I do have to drop a little Fedspeak economic jargon here), it is more closely aligned with intuitive, direct measures of trend headline inflation—like the 36-month centered average, or headline inflation’s average over the coming 24-month period—that we are only able to observe after the fact.[5]

Third, trimmed mean inflation has shown substantially less systematic bias. Over the past 10 years, looking only at data that would have been available to policymakers in real time, conventional core PCE inflation has averaged 1.65 percent—nearly 30 basis points below headline inflation’s 1.94 percent average. Meanwhile, trimmed mean inflation has come in at 1.83 percent—just 10 basis points below headline. Setting policy using conventional core as your guide is like navigating using a compass: It has a systematic bias and is influenced by local anomalies in the Earth’s magnetic field. Using the trimmed mean to set policy is more akin to navigating by GPS.

If you go to the Dallas Fed website, you will see our most recent posting: The 12-month trimmed mean rate held steady in December, staying within the 1.6 to 1.7 percent range it’s occupied every month since April 2014. That’s a lower range than we’re shooting for, but a whole lot less discouraging than an inflation reading of 0.75 percent or even 1.3 percent.

Unemployment trends give us additional reason not to be overly concerned about the current inflation shortfall.

Recently, Pope Francis gave a stern lecture to the College of Cardinals about the risks of what he termed “spiritual Alzheimer’s.” I worry that the FOMC, preoccupied with its 2 percent inflation target and understandably shy about moving too soon to lift off from the “zero bound,” is at risk of “monetary Alzheimer’s.”

My chief policy advisor, Evan Koenig, and I, and our Dallas research colleagues Anil Kumar and Pia Orrenius have authored papers that show the Phillips curve—the relationship between unemployment and wage growth—is not linear but convex, meaning that wage growth initially picks up slowly in response to unemployment rate declines, but as you approach maximum employment, inflation turns upward with increasing intensity. Up to now, we’ve been in picks-up-slowly territory, with wage and salary inflation rising 0.2 percentage points each year, from 1.5 percent in 2011, to 1.7 percent in 2012, to 1.9 percent in 2013 and to 2.1 percent in 2014. But if historical patterns hold, we’ll see larger and larger increments to wage inflation going forward.

Inflation responds to slack with a long lag in today’s world, where—thanks greatly to the efforts of Paul Volcker—confidence in the Federal Reserve’s commitment to price stability is strong. It’s easy for policymakers to take that confidence for granted, and understandable that they would want to push hard against real resource constraints in an effort to spread prosperity more broadly. However, as I have repeatedly reminded my FOMC colleagues, every single time the Fed has waited for full employment to be achieved before starting to withdraw accommodation, it has ended up driving the economy into recession. When policymakers get too clever by half, the public pays a steep price.

I liken monetary policy to piloting a ship, as I learned to do at the Naval Academy. When you are at the conn—at the wheel of a large ship—you begin to slow down miles before you reach your intended destination. There are no brakes you can slam on to make a sudden stop. Ship velocity, like monetary policy, operates with a lag. If we wait to see the whites of the eyes of full employment and then have to raise rates sharply, I believe it will shock the economy and invite an adverse reaction. So, taking a page from Pope Francis, I hope we don’t forget the past and will remember that the wisest policy option has proven to be early and gentle interest rate increases as we approach full employment.

Secretariat

During the financial crisis, I said we were “the best-looking horse in the glue factory.” The outlook was bleak everywhere, and we were hobbling along on unsure legs. Now, thanks in part to accommodative monetary policy and the indestructible force of American entrepreneurialism, most vividly demonstrated by George Mitchell and other innovators in the energy sector, and with no thanks to fiscal and regulatory shenanigans by a feckless Congress and White House, the U.S. economy is now racing down the track.

Our businesses used the downturn to tighten their expense structures and ramp up productivity and efficiency. They have used the accommodative monetary policy of the Fed and the abnormally low interest rates the Fed has engineered to clean up their balance sheets, replacing existing debt with lower-cost debt and also tightening up their equity structures, buying back shares and improving shareholder satisfaction by paying out higher dividends. During the depth of the crisis, one of my most esteemed colleagues on the FOMC noted that, looking at our banks’ balance sheets, “nothing on the right was right and nothing on the left was left.” Now both sides of the balance sheets of most U.S. companies, as well as banks, are healthier than they have been in decades.

Here is the point: Thanks to the Fed’s monetary policy and to their own ingenuity, private businesses in the U.S.A.—those that create real, lasting jobs—are well-groomed and fit and ready to run faster around the global track than the businesses of any other country.

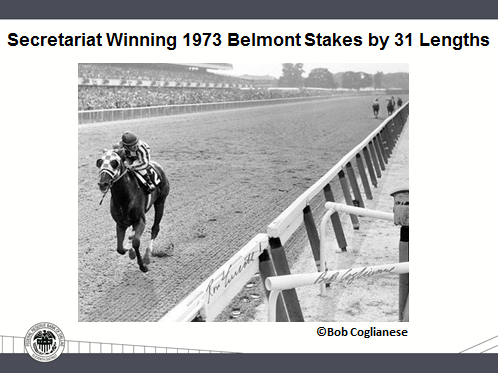

So let me conclude with the visual that I believe embodies the potential of our economy: that of Secretariat at the Belmont Stakes in 1973. And let me remind you that despite all the naysayers and doomsayers—those who said Europe would lap America, that Japan would lap America, that China would lap America, that the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India and China) would lap America, that America could not compete with the masses of low-cost labor that were unleashed in China and India and elsewhere by the end of the Cold War and with the advent of globalization—we are No. 1. The U.S. and its North American Free Trade Agreement partners, Mexico and Canada, form the most dynamic growth region of the world. We are Secretariat, and we can win the global economic race by 31 lengths if only we are given freer rein by fiscal and regulatory authorities.

G-6 to Gee Whiz

I was a child of the Cold War. We lived then under the threat of mutually assured destruction. The Wall came down. The Soviet Union disintegrated. Mao died. Communism was swept into the dustbin of history. Sure, we have the group formerly known as ISIS and the Taliban and other perpetrators of evil. But the great powers have turned from mutually assured destruction to mutually assured competition. When I was sent by Bob Roosa to work in the Carter administration and learn, in his words, “how government can screw things up,” we had a G-6—ourselves and five nations that we interfaced with economically: Canada, England, France, Italy and Germany. Now we have a Gee Whiz. There is a G-20, a G-30, a World Trade Organization and so on. We won! Every nation wants in on the economic prosperity; every nation wants to compete to better the living standards of its people.

We paid with precious blood and treasure to win the Cold War and create a world of mutually assured competition. And there is no country, no people, nobody anywhere on this planet who can outpace us. Nobody. Period.

Thank you.

And now, in the spirit of what every signatory to S. 264 worries about, I’d be happy to avoid answering your questions.

Notes

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve System.

- How to Speak Money, by John Lanchester, New York and London: W.W. Norton & Co., 2014, p. 74.

- From Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World, by Liaquat Ahamed, New York: Penguin, 2009.

- See note 2, p. 88.

- Keynesianism vs. Monetarism and Other Essays in Financial History, by Charles P. Kindleberger, New York: Rutledge, 1985, p. 2.

- “Trimmed Mean PCE Inflation,” by Jim Dolmas, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Research Working Paper no. 0506, July 2005.

About the Author

Richard W. Fisher served as president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas from April 2005 until his retirement in March 2015.