Pandemic economic lifeline: taxes on consumption, labor that fund stay-at-home subsidies

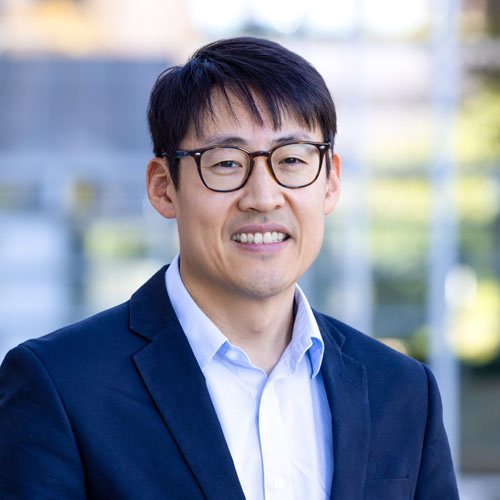

Despite various containment measures, another surge of COVID-19 cases began sweeping across the United States, Europe and the U.K. in the fall (Chart 1). Widespread availability of recently developed vaccines to slow and eventually halt the virus’ spread isn’t expected until mid-2021.

Thus, policymakers need tools to counteract not only the current public health and economic crisis, but also future pandemics. In a recent Dallas Fed working paper, I show that stay-at-home subsidies funded by taxes on consumption and labor can simultaneously reduce deaths and increase output.

One difficulty combating contagions such as COVID-19 stems from an economic concept called externalities. Externalities arise when individuals do not take into account the effects on others of their actions involving economic activities—such as consumption and labor—that contribute to viral transmission.

This phenomenon is complicated by the reality that the COVID-19 fatality rate is higher for some demographics and lower for others. Reluctance to wear masks can also be interpreted in this light.

Using taxes to address externalities

Fortunately, economists have an age-old solution for addressing externalities: Pigouvian taxes. Named for the British economist Arthur Cecil Pigou, a Pigouvian tax is a tax on economic activities that generate negative externalities. For example, in the case of carbon emissions—a classic externality—economists prefer to reduce the incidence of emissions with a carbon tax rather than setting restrictions on quantities. (For more on this, see this survey of economists.)

In the same vein, activities that increase infection risk for oneself and others such as consumption and labor can be subject to Pigouvian taxes rather than shut down. Furthermore, relative to the alternative of imposing no mitigation policy, providing stay-at-home subsidies through Pigouvian taxes can be Pareto-improving—meaning that policies are beneficial for all—and can increase economic output. (Vilfredo Pareto, an Italian economist, is best known for his work on wealth distribution.)

Modeling epidemiology and economic activity

To arrive at this conclusion, I develop a state-of-the art quantitative model that incorporates feedback between virus transmission and economic activities and allows for differences in age, income and wealth. Each of these model ingredients is necessary to study policies that aim to improve public health and economic outcomes.

The economic-epidemiological feedback allows for individuals to optimally change their behavior in response to not only the severity of the pandemic but also to various mitigation policies. These changes in behaviors, in turn, affect the severity of the pandemic. The model draws from an emerging literature that combines economic and epidemiological models.

Next, accounting for differences in age is crucial, as it is a key determinant of COVID-19’s fatality risk. Finally, individuals with different levels of income and wealth may respond differently to the pandemic and mitigation policies. In particular, lower-income and lower-wealth individuals may reduce their economic activities by less since most low-wage workers are unable to work from home, and low-wealth individuals cannot afford to stop working for a prolonged time.

Incorporating these differences allows the study of policies such as stay-at-home subsidies to be specifically targeted to those who might need them.

An alternative to stay-at-home orders

The model’s main finding is that relative to stay-at-home orders, a stay-at-home subsidy with Pigouvian taxes on virus-transmitting activities (consumption and labor) reduces deaths by more and output by less.

Under a blanket stay-at-home order, older individuals benefit because of a reduced infection and death probability; however, these gains are mostly offset by the losses of young/low-wage/low-wealth workers who experience a large decline in their income.

In contrast, the subsidy-and-tax policy can benefit all individuals. This is because while both policies result in reduced economic activities of young, low-wage/low-wealth workers, the subsidy-and-tax policy provides the incentives to do so, and a lockdown does not.

Neither policy has a direct effect on the labor supply of high-wage individuals who choose to work mostly from home during the pandemic. Additionally, retired individuals are willing to face higher consumption taxes in exchange for a lower infection risk.

A second finding is that the stay-at-home subsidy and Pigouvian tax policy can simultaneously improve public health and economic objectives. I focus on a version of the model—outlined in the paper—that funds the subsidy with consumption and labor income taxes. The output maximizing policy involves a weekly subsidy of $450 to individuals with no weekly earnings, a 2 percent tax on consumption and labor income, and no stay-at-home order.

The policy, starting March 27, 2020, and gradually phasing out after Jan. 29, 2021, reduces deaths by 20 percent and increases two-year output by 5.5 percentage points, compared with no mitigation.

Saving lives while aiding output via direct, indirect effects

Compared with no mitigation, the output increase results from two opposing effects. The first is the direct effect: The stay-at-home subsidy and the tax on labor provide incentives to reduce hours, which leads to less output. The aggregate effect is small for subsidies less than $600 per week because the payments only change the behavior of low-wage workers.

The second is an indirect effect: The reduction in infection and death rates resulting from the mitigation policy partly reverses the voluntary reductions in hours worked from higher-wage workers. For mitigation policies with moderate subsidy amounts, the indirect effect dominates, improving both economic and health objectives.

Various mitigation scenarios compared

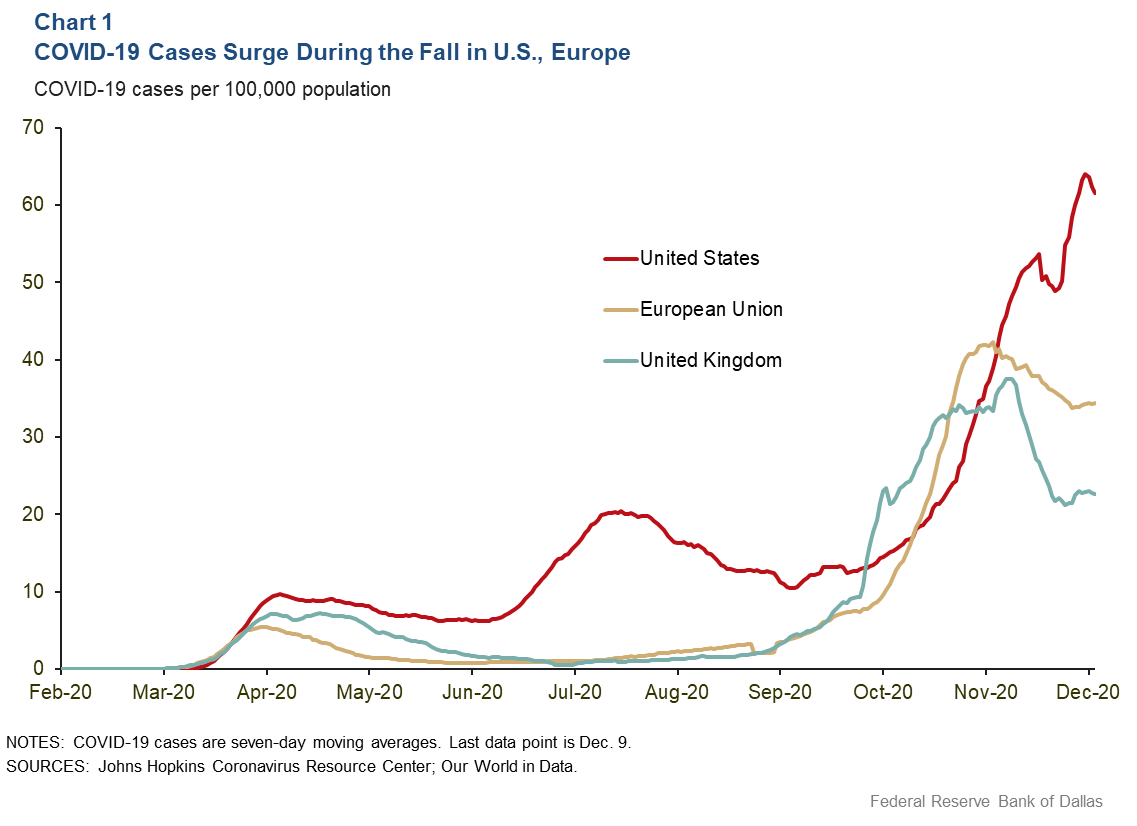

Chart 2 plots output and lives saved for various mitigation policies. There are several takeaways.

First, even in the absence of mitigation policies, the pandemic leads to a large recession—a 10 percent output decline—mostly driven by the voluntary reductions in labor by individuals in response to the pandemic.

Second, when considering only stay-at-home orders (lockdowns), saving lives necessarily reduces output relative to no mitigation, generating a trade-off between lives and output, as can be seen by the downward-sloping red line.

Third, the frontier policies (green line), which plots the best policy mix to deliver the most output for any level of lives saved, features no trade-off to the left of the output maximizing policy; starting at no mitigation (lives saved 0 and output 90), both lives are saved and output goes up along the frontier. To the right of the output maximizing point, a trade-off occurs; implementing policies that save more lives also forces output lower.

Finally, the constrained optimal policy (the Pareto improvement that saves the most lives) reduces deaths by 27 percent and two-year output by 1.7 percentage points, compared with no mitigation. The policy—which begins March 27, 2020, and lasts for the duration of the pandemic—involves a weekly subsidy of $675 to individuals with no weekly earnings, a 6 percent tax on consumption and labor income, and no stay-at-home order.

Qualifying the model findings

The model is a simplification of reality, as all economic models are. The simplifications allow us to illuminate key mechanisms, but what’s missing could well have implications for the prescriptions the model suggests. For example, the model abstracts from contact tracing, testing and quarantine measures, which have been successful in other countries such as Japan and South Korea. That said, the model indicates that stay-at-home subsidies, funded by Pigouvian taxes on virus-transmitting activities (consumption and labor), can save lives and the economy.

The research also has implications for the optimal containment policies in response to the recent positive news regarding vaccine development. In particular, the research shows that an earlier arrival of a vaccine necessitates stronger mitigation efforts. This is because more lives can be saved with a shorter economic contraction.