Largest Texas metros lure big-city, coastal migrants during pandemic

Texas has been a magnet, drawing people and firms from around the country over the past decade. Pull factors include plentiful job opportunities, an accommodative business environment and a relatively low cost of living.[1]

Even with those attributes, when the COVID-19 pandemic struck, it was unclear how migration to the state would be affected.

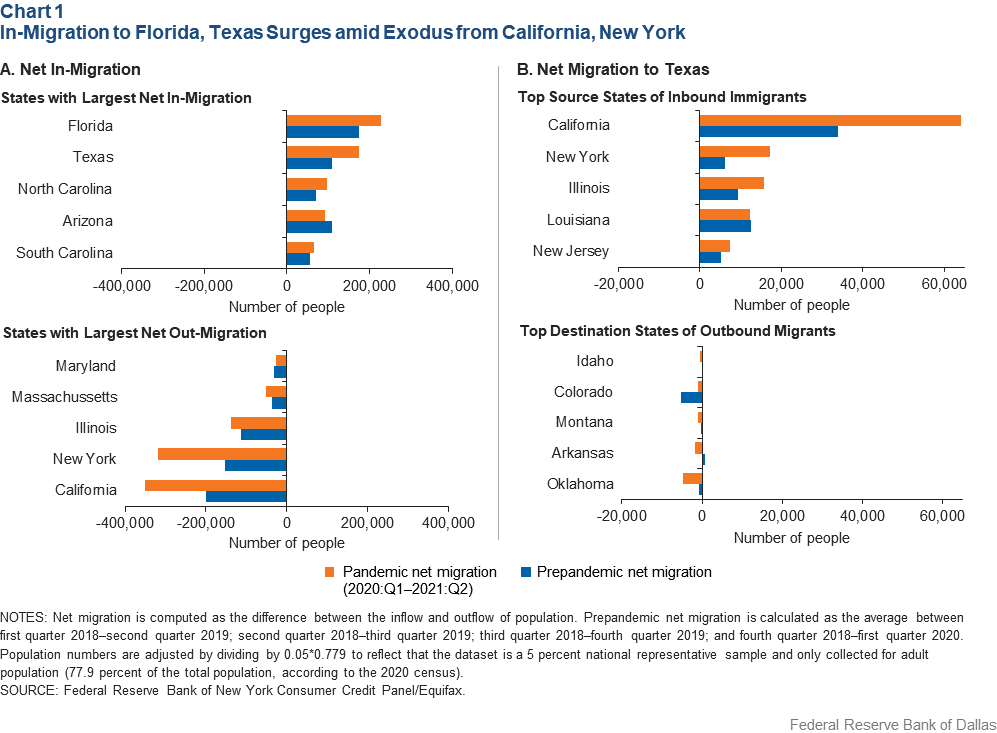

Almost two years since the pandemic began, high-frequency data based on credit-bureau address changes show that migration to Texas sped up, increasing from already-high levels. The state received 174,000 migrants on net in the five quarters following the onset of the pandemic, up from 109,000 in the previous five quarters.[2]

On the Move

Chart 1A shows the estimated net inflow of interstate migrants from the start of the pandemic (first quarter 2020) to second quarter 2021 based on the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax data.[3] The migration statistics are based on address changes reported to the credit bureau of adults with credit reports. (About 80 percent of adults have credit reports.)[4]

In contrast to Texas, states such as California and New York experienced population exodus during the pandemic, raising already-elevated out-migration to new highs. Of note, despite rapid in-migration, Texas remained the second-largest net recipient of migrants behind Florida.[5] And since Texas has a large population, 13 states have higher rates of net in-migration than Texas.

Much of Texas’ population gain comes from people exiting California and New York (Chart 1B). Since before the pandemic, California has been by far the largest population feeder state for Texas. The number of Californians coming to Texas roughly doubled from 34,000 to 64,000 during the initial 18 months of the pandemic.

Net moves to Texas from New York and Illinois also increased—partly because of a large exodus from big metros such as New York and Chicago.

But Texas also suffered losses, sending more people than it received to a few states—notably, Oklahoma, Arkansas and Montana—though the numbers were small relative to the gains from California and New York.

Pandemic-Related Migration

Many factors led to the spike in migration to Texas during the pandemic.

At the onset, many workers were forced to shelter at home as telecommuting was quickly adopted and became commonplace. Thus, even as COVID-19 cases subsided, the widespread adoption of distance-work technology allowed many people to continue working remotely and avoid commuting to offices.

Workers no longer tied to an office considered relocating to more attractive and more affordable metros or states, different from where their employers were located.

Cities such as New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco host a disproportionately high share of jobs that offer the option to work from home (finance, media, tech). These metros also have the highest cost of living among all of the nation’s major cities.[6] Sizable portions of their residents moved to other, more affordable metros as workers took advantage of newfound mobility.[7]

Before the pandemic, many workers had no choice but to remain in the high-cost states because of the strong agglomeration of high-wage jobs there. For example, high-wage tech jobs are especially concentrated in California’s Silicon Valley. Those working in the industry could not easily move away despite the extraordinarily high housing costs.[8]

Similar pockets of industry clusters exist elsewhere—in New York and Los Angeles—which tied workers to the cities of their employers. The option of remote work removed these constraints, unleashing a wave of migration. In addition, some firms also moved, bringing their workers with them. (Prepandemic research has shown that firm relocations are generally responsible for a small fraction of Texas job growth.)

As such individuals relocate, they bring their demand for local services with them to their new home cities and metros, stimulating business and creating jobs in the destination locations. In contrast, locations experiencing a large population exodus confront a rapid decrease in local demand for services, which leads to slower local job growth. The difference in local job opportunities encouraged many workers in the service sector with no option to work remotely to also join the wave of migrants.

Texas Metros’ Migration Influx

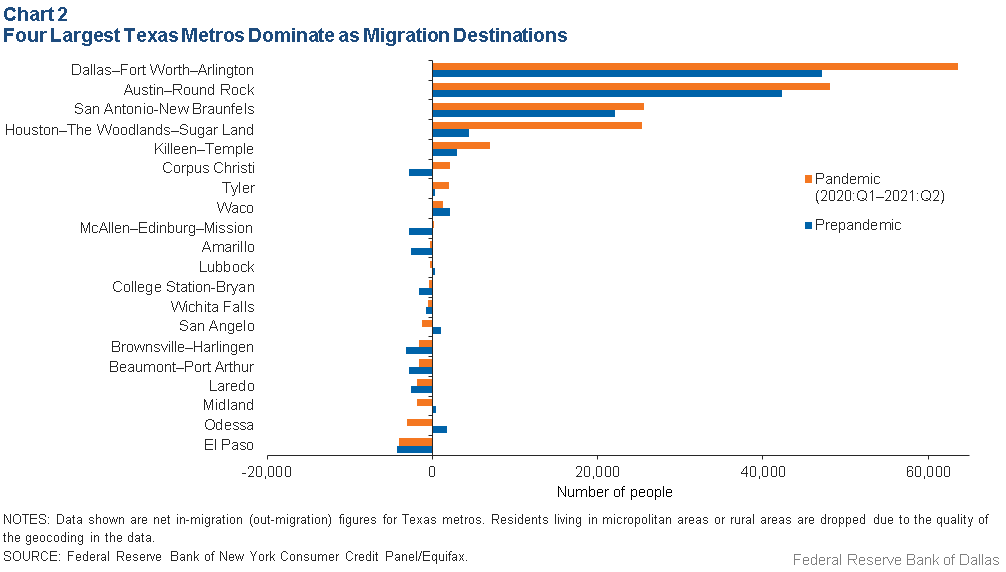

Migration to Texas during the pandemic has been overwhelmingly to the four largest Texas metros (Chart 2).

The Dallas–Fort Worth area led the state in the number of net in-migrants, followed by Austin, which topped the metros in a related metric, the migration rate—net in-migrants relative to population.

Migration toward smaller metros in Texas also increased. Before the pandemic, most smaller metros in Texas lost population on net. But during the pandemic, most of these metros either experienced a decrease in the net outflow of people or began gaining population.

Corpus Christi, for example, turned from a net outflow before the pandemic to a net inflow during it. Other metros such as Beaumont–Port Arthur, Brownsville–Harlingen and Laredo continued to experience a net outflow of population but at a much-reduced level.

The Midland–Odessa area is a notable exception. It began losing population after the pandemic began. The sudden spike in outward migration is likely due to the large job loss in the energy sector in 2020. Out-migration also continued in El Paso, where it has occurred for some time.

Coastal Cities’ Relocation

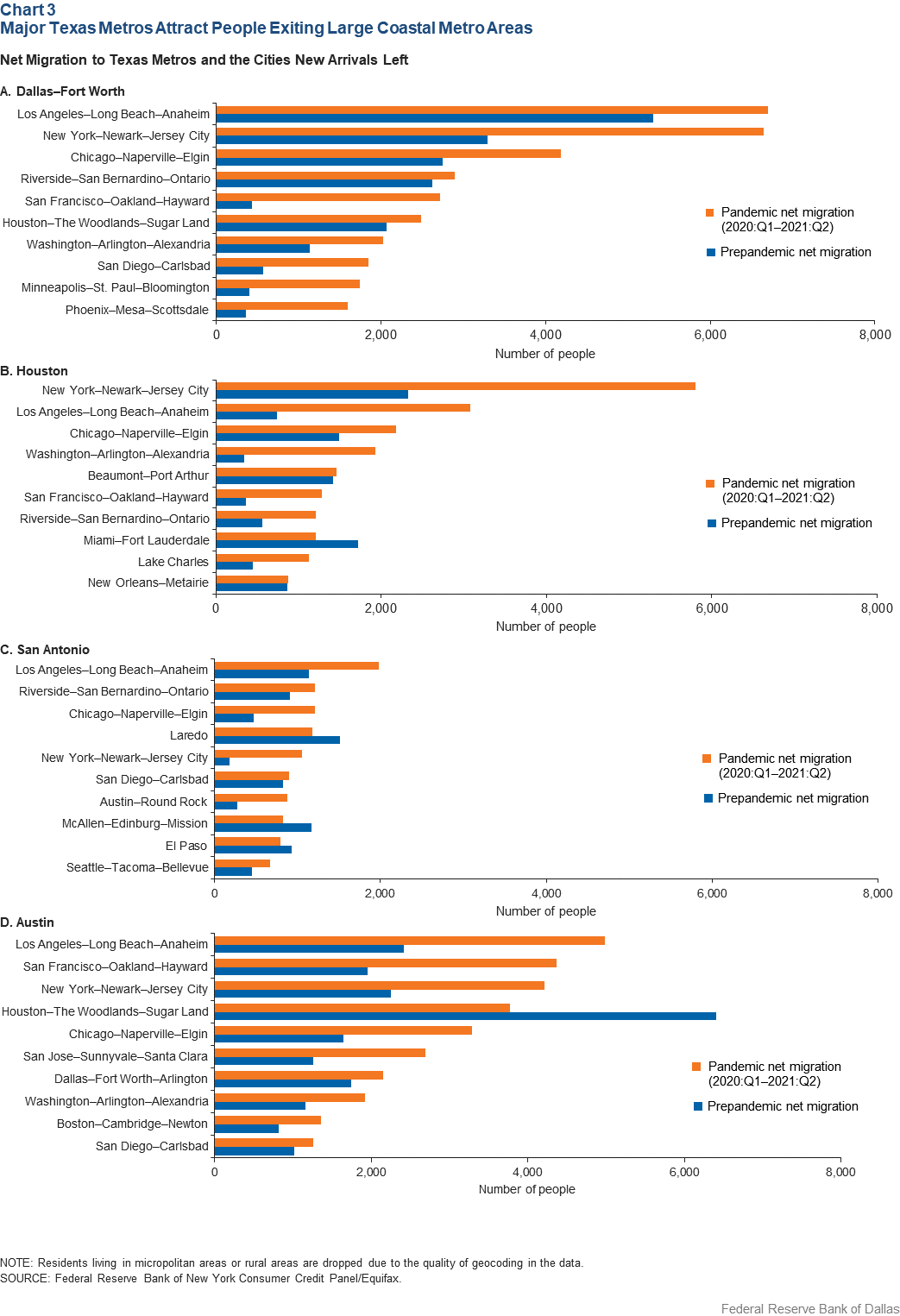

Four major Texas metros gained population from the nation’s largest non-Texas metropolitan areas during the pandemic, particularly high-cost locales such as New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco (Chart 3).

In particular, Dallas–Fort Worth and Austin saw the most robust inflow of people from the largest and most expensive metros outside of Texas. Houston and San Antonio saw a smaller stream of net in-migration from these areas.

The inflows to Texas metros have brought considerable talent from those high-skilled labor markets on the coasts. Austin, for example, is a likely beneficiary of a large movement of talent, particularly in the high-tech sector. Net migration from the combined metro areas of San Francisco and San Jose (Silicon Valley) has been the biggest out-of-state contributor to Austin’s in-migration, doubling since the start of the pandemic.

The growing talent pool in Texas may, in turn, become a magnet for relocating firms searching for local talent.

Notably, Texas metros are not the only destination for coastal migrants.[9] The migration statistics indicate that smaller and lower-cost metros all over the nation have gained population at the expense of these traditionally large, high-cost coastal metros.

Suburban Inflow

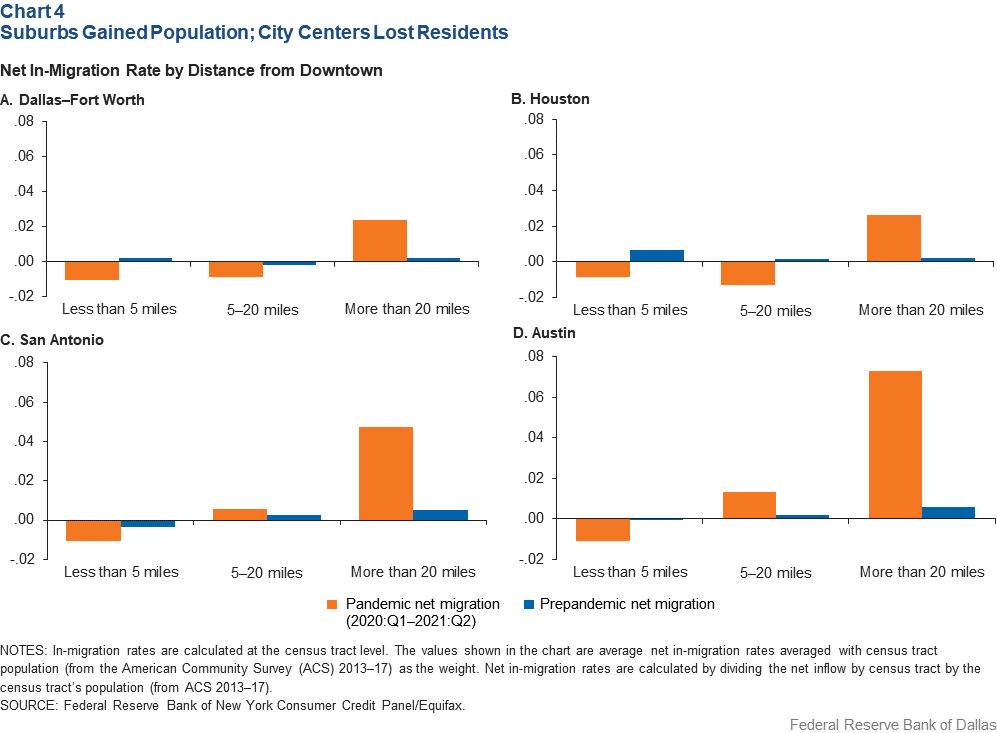

Population gains in the four major Texas metro areas with the largest inflows have occurred primarily in the suburbs (Chart 4).

In all four metros, the pandemic-era net migration rates skyrocketed in neighborhoods farther than 20 miles from downtown. In contrast, there was either modest growth or population loss in neighborhoods within five to 20 miles of downtown.[10] This contrasts with the prepandemic growth patterns within the Texas metros, where the city centers were in demand, particularly among high-income and college-educated individuals.[11]

The important reason behind the suburbs’ heightened popularity during the pandemic is the increased prevalence of the option to work remotely. As this arrangement becomes commonplace for office jobs, the reduced need to commute to job centers—city centers or office parks—allows people to relocate to more-remote neighborhoods, which provide cheaper, more-spacious living areas.

Migration Pains

The in-migration from the crowded coastal cities to Texas metros has brought additional workers and their talents, and firms and their investment, which have collectively fueled the state’s sustained economic growth.

But with these gains comes some pain. The large inflow of people has likely contributed to rising apartment rents and home prices, especially at a time of shortages in construction materials and labor. Additionally, the rapid increase in migrants to Texas has added pressure on existing infrastructure such as roads and bridges, hospitals, utilities and educational resources.

Future Destination

Will the newly arrived transplants stay in Texas permanently? Will the current migration flow continue or reverse? The answers depend on a few factors.

One determinant of the future flow of population is the extent to which work will return to the physical office locations over the long run. Studies have shown that while a return to offices may start to pick up once the pandemic weakens, a large portion of the workforce may continue to telecommute or adapt to a hybrid model due to the widespread adoption of work-from-home technologies such as Zoom and Slack.[12]

This could imply that more people may continue to migrate to Texas and that a significant portion of the transplants who have moved here may stick around long term.

Another factor is whether Texas’ cost advantage over states such as California and New York can be maintained as more people move in. Timely expansion of affordable housing could certainly help relieve those price pressures.

Notes

- “Gone to Texas: Migration Vital to Growth in the Lone Star State,” by Pia Orrenius, Alexander T. Abraham and Stephanie Gullo, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, First Quarter, 2018; “Texas Top-Ranked State for Firm Relocations,” by Anil Kumar and Alexander T. Abraham, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Fourth Quarter, 2018.

- The five-quarter prepandemic net migration is calculated as the average between: first quarter 2018–second quarter 2019; second quarter 2018–third quarter 2019; third quarter 2018–fourth quarter 2019; and fourth quarter 2018–first quarter 2020.

- This panel is a nationally representative random anonymous sample of individuals drawn from the Equifax credit report data. The data report consumers’ address changes over time as their billing addresses change. Based on the aggregated statistics of these changes of addresses, researchers can study how the direction of migration changes with fine geographic detail at a high frequency (quarterly).

- See Data Point: Credit Invisibles, by Kenneth P. Brevoort, Philipp Grimm and Michelle Kambara, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Office of Research, May 2015.

- Many Florida in-migrants are retirees, while migrants to Texas tend to be workers.

- The migration patterns in the consumer credit panel show that metros with a higher share of workers with telework options saw a much-larger outflow of population. See also “How Many Jobs Can Be Done At Home?” by Jonathan I. Dingel and Brent Neiman, Journal of Public Economics, vol. 189, September 2020.

- “The Geography of Remote Work,” by Lukas Althoff, Fabian Eckert, Sharat Ganapati and Conor Walsh, National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper 29181, August 2021.

- To look more into the spatial sorting and housing cost research, see “Real Wage Inequality,” by Enrico Moretti, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2013, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 65–103, and “The Determinants and Welfare Implications of U.S. Workers’ Diverging Location Choices by Skill: 1980–2000,” by Rebecca Diamond, American Economic Review, vol. 106, no. 3, pp. 479–524, March 2016.

- The migration patterns seen in the consumer credit panel indicate that less-populous metros have been gaining population, while the more populous metros have been losing population since the start of the pandemic. “Remote Workers Can Live Anywhere. These Cities (and Small Towns) Are Luring Them with Perks,” by Jon Kamp, Wall Street Journal, Oct. 9, 2021.

- The movement of population toward the suburbs is consistent with the evidence documented in “COVID-19 Fuels Sudden, Surging Demand for Suburban Housing,” by Laila Assanie and Yichen Su, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Fourth Quarter, 2020. The authors show a significant outward shift in housing demand at the onset of the pandemic.

- “Gentrification Transforming Neighborhoods in Big Texas Cities,” by Yichen Su, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Fourth Quarter, 2019.

- “Hybrid Is the Future of Work,” by Nicholas Bloom, Policy Brief, Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, June 2021.

About the Authors

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2021/swe2104.