Strength in consumer spending does not necessarily imply low probability of recession

Consumption—expenditures on goods and services—has increased at a solid pace since the beginning of 2023. Real (inflation-adjusted) personal consumption expenditures (PCE) grew at a 2.6 percent annualized rate during the first three quarters, contributing 1.7 percentage points to the 3.1 percent real GDP growth. This creates a perception that a recession is unlikely in the near term.

Looking at historical data, however, we document that consumption was not a main driver of GDP declines in previous recessions and that a recession is not necessarily preceded by declines in consumer spending. We highlight the importance of private fixed investment in explaining GDP declines during past recessions. Residential investment, in particular, is typically a key predictor of future recessions and worth watching when assessing whether the Fed can achieve a soft landing.

Consumption and investment dynamics during recessions

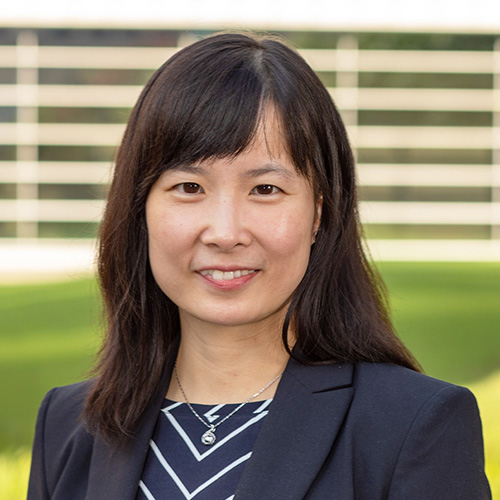

Real GDP has declined during every recession since the 1960s, apart from a mild 2001 episode following the collapse of the dotcom bubble. During these recessionary quarters, the average decline in GDP was 1.7 percent annualized, excluding the extraordinary pandemic-induced recession in 2020 (Chart 1).

Given consumer spending’s dominant share in the U.S. economy (about two-thirds), one would expect consumption to be a main contributor to GDP declines in a typical recession. This is not the case. Chart 1 shows that not every recession is accompanied by a contraction in consumption (for example, 1970, 1982 and 2001). Even during episodes when consumption fell meaningfully, it was not the main driver of the GDP declines. On average, consumption grew modestly during previous recessions and, if anything, contributed positively to changes in GDP.

In contrast, real private fixed investment, which includes residential investment and business (nonresidential) investment, fell in every recession and tended to be the key driver of GDP declines during recessions.

On average, private fixed investment accounted for 93 percent (or 1.6 percentage points) of the 1.7-percentage-point GDP decline in a recession. A further breakdown shows that both residential and business investment meaningfully contributed to these GDP declines—residential investment accounting for 35 percent (or 0.6 percentage points) and business investment responsible for 58 percent (or 1.0 percentage points).

Consumption and investment dynamics before recessions

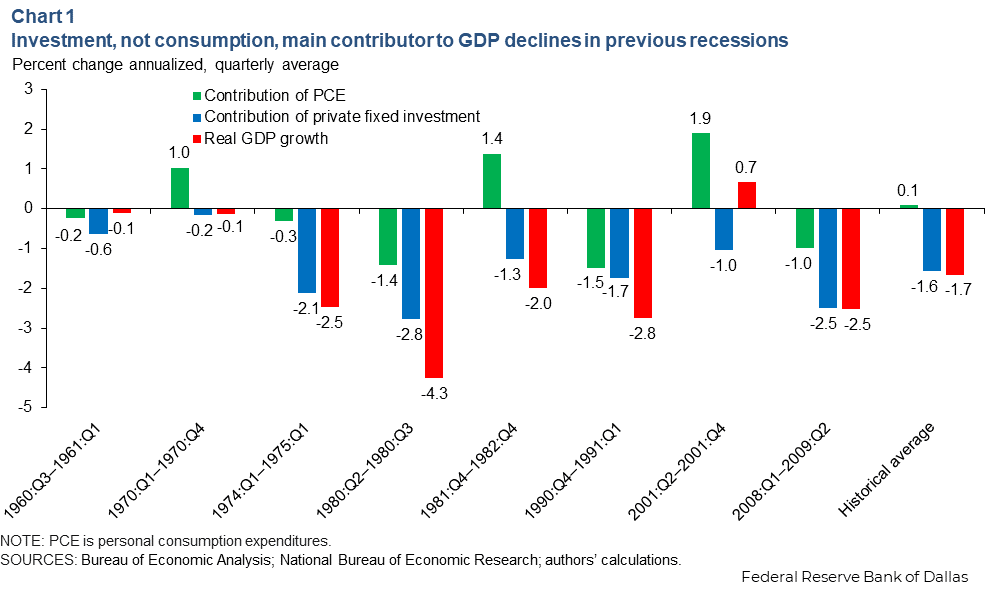

Strong recent economic data raise the question of whether a near-term recession is unlikely given the current robustness of consumer spending. To this end, we look at consumption and investment growth in the period leading up to a recession. We present patterns for the two quarters prior, but the observations are similar when we look at alternative time windows (for example, one and three quarters prior).

Chart 2 shows that in every recessionary episode since the 1960s, consumption grew in the two quarters before a recession. Consumption was also the main driver of GDP growth during the two-quarter period. While the economy expands 1.4 percent (annual rate) on average, 1.1 percentage points (or 82 percent) of that increase came from consumption.

In 2023, consumption’s contribution to GDP growth, although surprisingly strong, has been within the historical range, with similar magnitudes observed in 1970, 2001 and 2008. The main difference, however, is the contribution of private fixed investment. Investment typically declines before a recession, whereas it has been expanding recently.

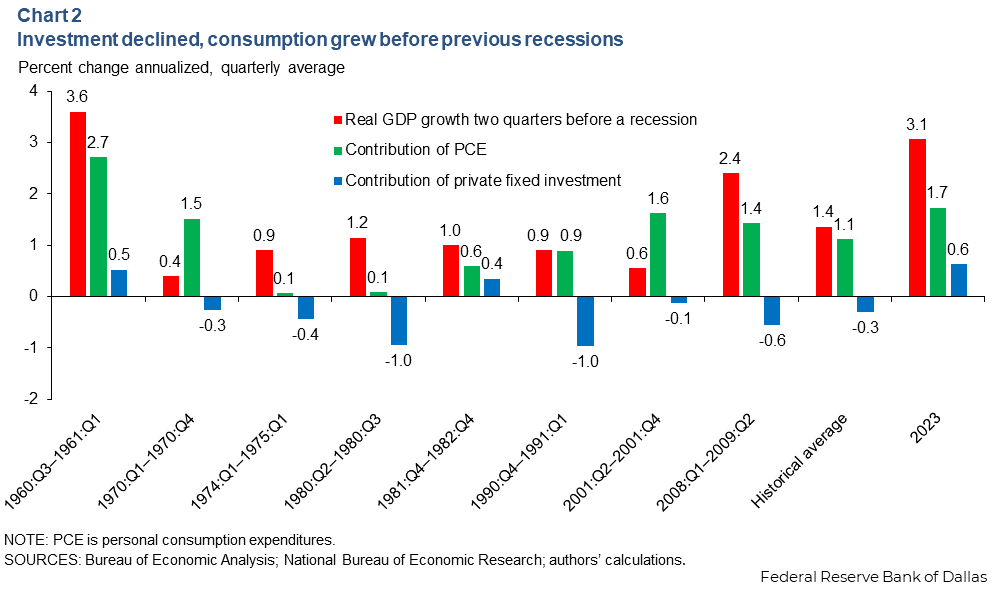

A further breakdown of investment paints a clearer picture (Chart 3). In previous episodes, it was residential investment, not business investment, that fell substantially and drove the investment decline before the recession arrived.

In the second half of 2022, residential investment was indeed a strong drag, and many analysts believed that the U.S. economy would go into a recession. As of December 2022, the Blue Chip Consensus Forecast for 2023 real GDP growth was just 0.3 percent with a 62 percent probability of a recession.

The economy, however, turned out to be far more resilient than anticipated; the latest Blue Chip Consensus Forecast for 2023 real growth has increased to 2.4 percent. Unlike the past, recent residential investment declines did not spill over to the rest of the economy. In fact, residential investment had no contribution to real GDP growth over the last two quarters after being a 1.3-percentage-point drag in the second half of 2022.

What is the outlook for residential investment?

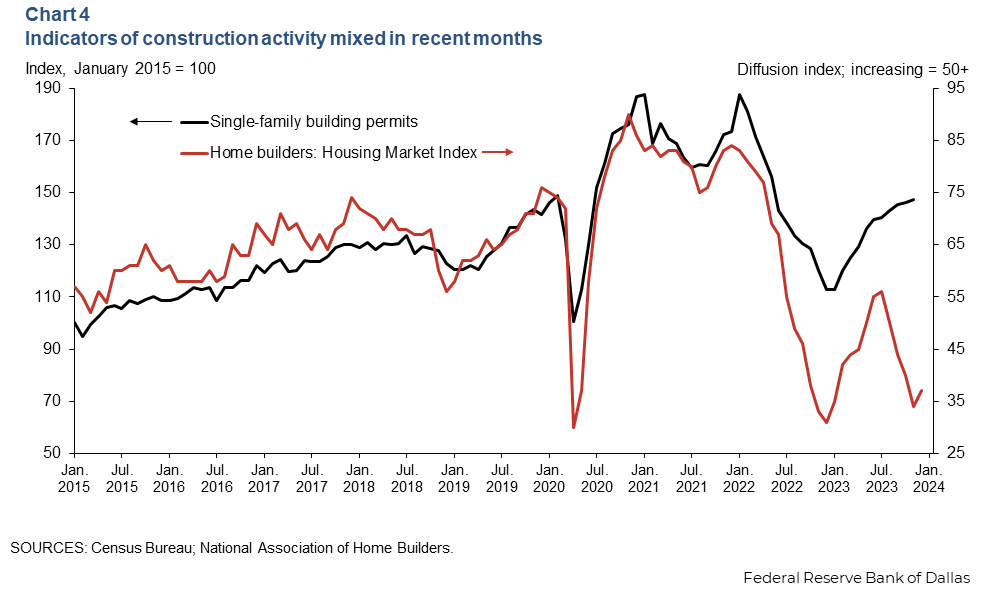

While the 2022 downturn in residential investment did not translate into a recession as many had thought, history tells us that it is an important leading indicator. The National Association of Home Builders Housing Market Index has sharply declined from its July 2023 peak and, as of mid-December, was close to its 2022 lows (Chart 4).

The increased pessimism suggests that residential investment could weaken and raise near-term recession risks.

However, there are two notable signals pushing back against this conclusion. First, over the past couple of months, the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage has declined more than 1 percentage point and returned to early summer levels. Second, as of November, housing permits and starts are well above 2022 lows and show no sign of decreasing despite the sharp decline in the Housing Market Index.

This indicates that poor sentiment has yet to translate directly into construction activity. Going forward, the key question is whether such buoyancy will continue and help the Fed achieve a soft landing.

About the authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.