Young adults are disconnected from work and school due to long-term labor force trends

Recent media attention has centered around the rising number of youths who opted out of school and the labor market during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. When disengaging from these wealth- and income-building opportunities, young adults face long-term disadvantages that, in the aggregate, could contribute to a less-skilled workforce in the future. Previously, we estimated that both a decline in school enrollment and a reduction in labor force participation contributed to a pandemic-era surge in disconnected youth. This follow-up series of articles examines whether this is true over a longer time period. In contrast to our previous results, we find that the main reason for rising disconnection since the 1990s is a decrease in labor force participation.

Disconnected youths (often referred to as “opportunity youth”) are young people who are neither in school nor working, missing opportunities to both earn and learn. They are also more likely to suffer from challenges in adulthood such as lower lifetime earnings, a greater chance of unemployment and poorer health. Disconnection therefore affects labor force productivity in the long run. This means helping these youths return to work or school provides short- and long-term benefits for them and their potential employers alike.

This article, the first in a series of two, finds that:

- For the subgroup of 18-to-24-year-olds, disconnection rates have increased since the late 1990s.

- Both disconnection factors—absence from the labor force and from school—are closely linked to business cycles. Between 2001 and 2019, labor force participation moved in the same direction as the economy, while school enrollment moved in the opposite direction.

- The pandemic has significantly worsened both aspects of disconnectedness.

- Between the late 1990s and early 2010s, school enrollment rates rose, but not consistently and not by enough to offset the decline in young workers, which explains the climbing disconnection rates.

- The share of disconnected young adults and its growth vary by state, with Texas’ share being slightly higher than the nation’s in 2019.

Methodology

Our approach differs from other opportunity youth research in two significant ways. First, this article focuses on disconnected young adults who are ages 18–24. Traditionally, opportunity youths are defined as those ages 16–24. We leave out 16-to-17-year-olds in order to better understand the age group that typically chooses whether to attend college or join the labor force. Second, opportunity youths are traditionally defined based on whether they are working. We focus instead on labor force participation so those who are actively looking for a job are not counted as disconnected from the economy.

Using data from the Current Population Survey, we identified disconnected young adults ages 18–24 who were not in the labor force and not enrolled in school[1]. The disconnection rates were averaged from all months in each year except June through August because students could be miscalculated as disconnected during the summer.

Share of disconnected young adults rose for two decades

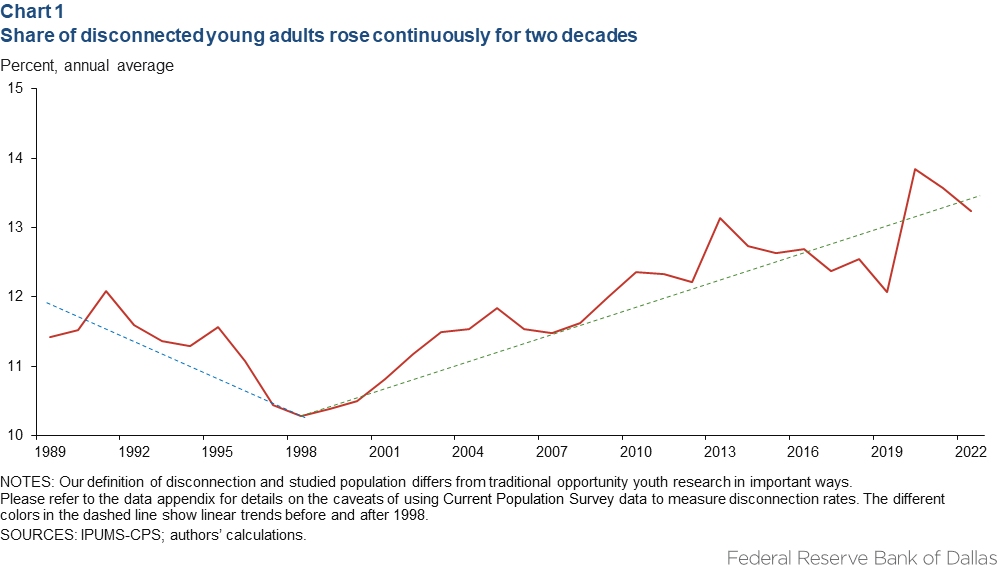

In order to place the disconnection that happened during the pandemic in broader economic context, we extend the data series back to 1989 when the enrollment numbers first became continuously available. Chart 1 shows the percent of young adults who were disconnected each year since 1989. This percentage, called the disconnection rate, fell briefly in the early and mid-1990s but has climbed steadily since, reaching a historical high of 13.8 percent in 2020.

This trend reveals that the problem of disconnected young adults is a long-term issue that was exacerbated by the onset of the pandemic. This means that if the disconnection rate returned to prepandemic levels, it would still be historically high.

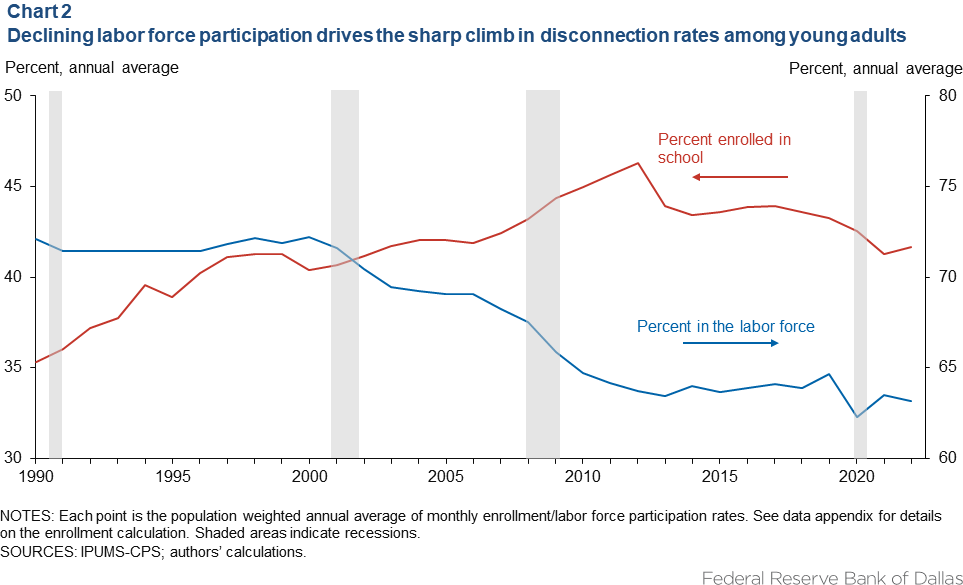

Next, we explore the main reason for this long-term trend. In Chart 2, we disaggregate the two elements of disconnection—labor force participation and school enrollment—in order to identify the source of increase since the late 1990s. In doing so, we find that the rising rate of disconnection is a combined effect of a stagnant enrollment rate and declining labor force participation. In fact, the labor force participation rate dropped by about 8.5 percentage points from 2000 through 2015, largely due to the Great Recession, and never recovered. The labor market challenges young adults experienced during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, while substantial, were much smaller when compared with earlier trends.

Education often serves as a channel to absorb young adults disconnected from the labor force during economic downturns. While school enrollment increased in general throughout the time period of our study, enrollment also ticked up during recessions (the shaded areas in Chart 2). We found this to be true until the COVID-19 recession in 2020, during which in-person education became less attractive due to the disease. However, during the recessions between 2000 and 2010, we also saw a decline in labor force participation that was never recovered. The increase in enrollment was therefore not enough to offset the decline in young adults’ labor force participation.

Growth in disconnected young adults differs by state

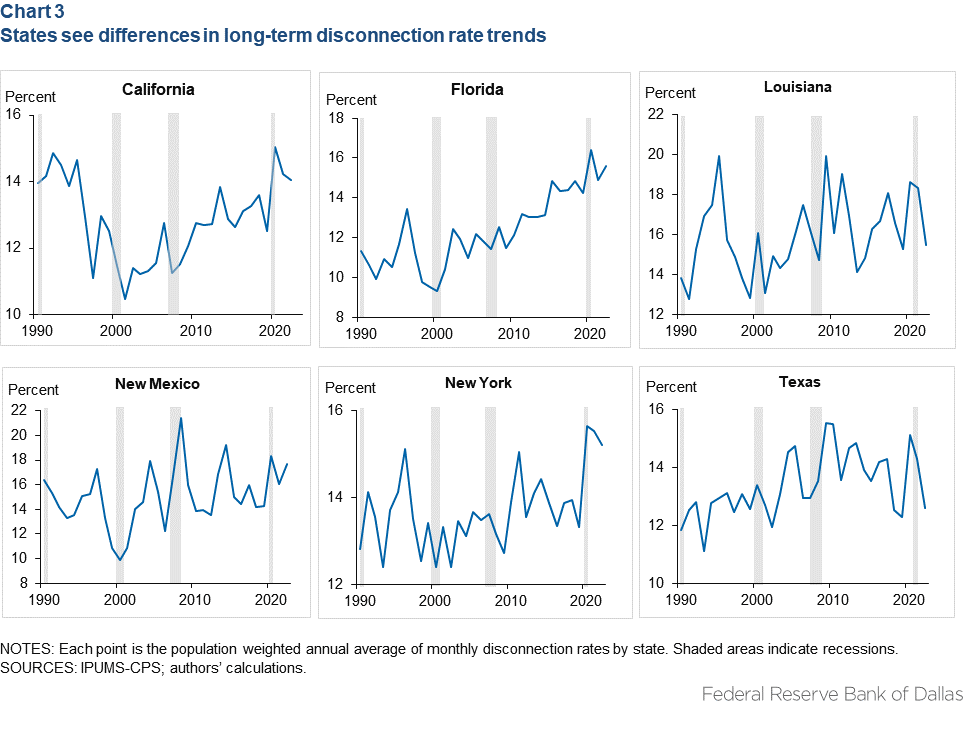

A comparison of the historical trends shows that some states have experienced significant increases in the share of disconnected young adults since the late 1990s, while other states did not. Among the most-populous states, California and Florida have experienced sharp increases in the share of disconnected young adults since the end of the 1990s (Chart 3). In contrast, New York had a very different experience, where the share of disconnected young adults did not increase much until the pandemic began. States in the Eleventh District—Texas, New Mexico and Louisiana—have experienced elevated disconnection rates since the Great Recession but showed distinctly different patterns than the other states mentioned.

A comparison of the disconnection rates shows that Louisiana and New Mexico, on average, had a higher level of disconnection rates compared with the other four states. In 2019 (the most recent year with sufficient data), Louisiana had an annual monthly average disconnection rate of 15 percent and New Mexico an average of 14 percent, ranking them sixth and eighth highest in the nation, respectively. The highest-ranking state was Alabama at 18 percent, and the lowest was New Hampshire at 7 percent. Texas ranked 21st at 12 percent.

Summary

This article shows that the sharp rise in disconnected young adults during the pandemic is the exacerbation of a problem that has gradually worsened in the past two decades. While attention was paid to decreases in school enrollment during the pandemic, finding long-term solutions to both employment and enrollment are important to reduce disconnection among young adults.

In the second article in this series, we will dive deeper into the historical trends of disconnected young adults. It will shed light on the gender and racial/ethnic differences and their implications for reengagement efforts.

Notes

- The technical appendix of this series is available here.

About the authors