EITC increases labor force participation among married Black mothers

Research has shown that the Earned Income Tax Credit, the largest of the U.S. antipoverty programs, boosts labor force participation among single mothers. It does not, in the aggregate, have the same effect on married mothers.

As policymakers continue to debate the merits of the EITC, we take a deeper look at the tax credit’s effect on women’s employment and discover that it has a work-encouraging effect for one group of married mothers. In this second article in our series on the EITC, we find that the tax credit increases labor force participation among married Black mothers.

The EITC offers low- to moderate-income families a subsidy for working. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers increased the maximum credit available through the program. Since then, they have periodically discussed making the expansion permanent. This article provides more in-depth data to foster greater understanding of the EITC’s full effect.

Labor market response to EITC

Our research uses Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) to study women’s labor market response to the EITC by race.[1] We find that:

- The EITC increases employment among single mothers. It also promotes employment among married Black mothers.

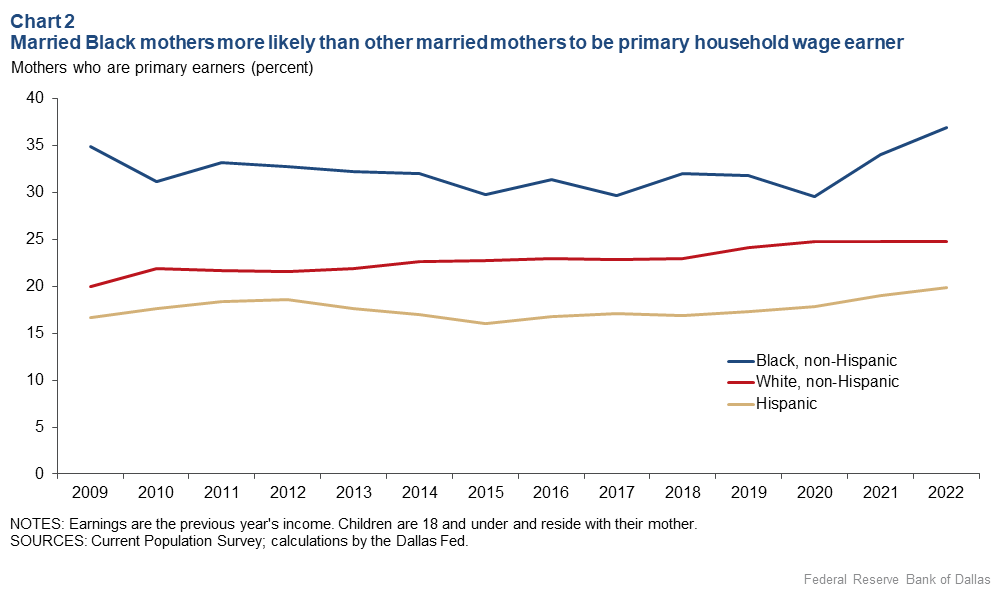

- Married Black mothers are 12 percentage points more likely to be the primary household earner than white married mothers.

- The share of female primary earners increased faster among Black households than Hispanic and white households during the pandemic.

When the EITC was introduced, it increased maternal employment by an estimated 6 percent.

The tax credit’s effects on single mothers of all racial groups are well-documented. Every $1,000 increase in maximum EITC benefits boosts annual employment of single mothers by around 3 percent. The EITC has an even stronger work-encouraging effect among single mothers with two or more children, perhaps because the EITC formula provides more generous benefits for single women with multiple children. EITC funds help parents afford child care, thus enabling them to join the workforce.

Why does the EITC tend to promote employment among single mothers but not most married mothers? The reasons are complex. The size of a family’s benefit is determined by household income. Prior research has found that EITC expansions increase the labor participation of married men but, on average, induce married women to leave the labor force. This is in part because married women are disproportionately secondary earners who earn less than their spouses, and they therefore optimize labor market decisions based in part on the income of their spouses.

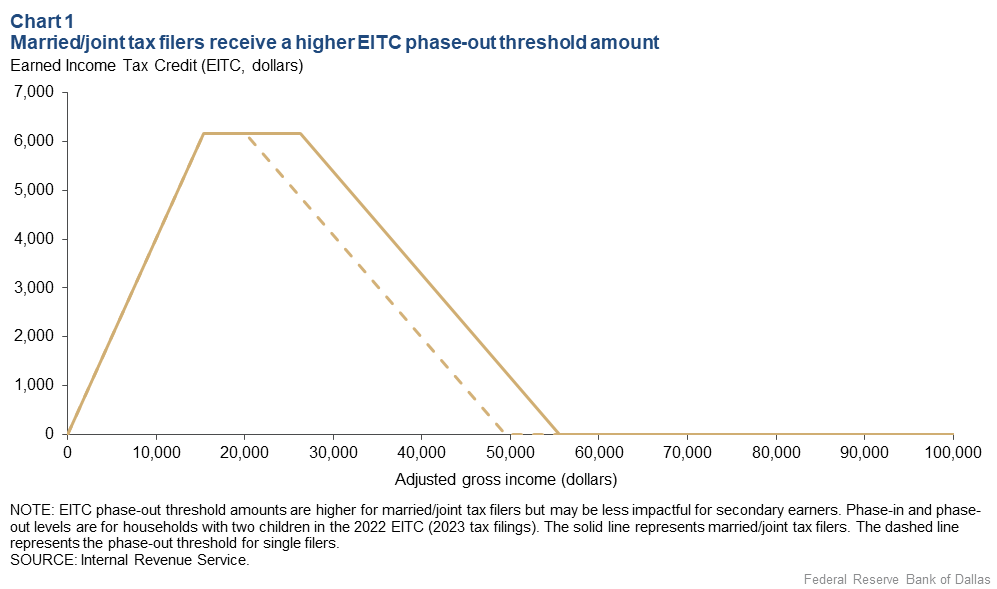

Secondary earners also have different incentives than primary earners or single filers. Joint-filing households’ marginal tax rates are determined by income under the EITC. Married couples whose combined income is high enough to land them in the phase-out region (say $30,000) would receive lower tax benefits per marginal dollar earned (Chart 1). As a result, the EITC may be less impactful for secondary earners—mostly married women.

Research by Yang Jiao, Yi Lu and Xiaohan Zhang (2022) finds that race factors into how the EITC impacts married mothers. While the EITC increases the employment of white and Black single mothers equally, it increases the employment of only married Black mothers (the effect on white mothers is statistically insignificant).

Why does a racial disparity exist between married mothers but not between single mothers? One reason lies in intra-household income dynamics.

Higher share of primary earners among Black mothers

Married Black mothers are historically more likely to be the primary household earner than white or Hispanic married mothers. In 2009, 1-in-3 married Black mothers in the U.S. were the primary earner (Chart 2). Meanwhile, only 1-in-5 white married mothers and 1-in-6 Hispanic married mothers earned more than their spouse. Over a decade later, this pattern still holds true. It has also become more pronounced since the pandemic began.

EITC and racial income gaps

If the EITC has a larger positive impact on primary earners, the fact that Black married women are more likely to be primary earners implies that EITC expansion could reduce family income gaps between Black and white households. The EITC has been shown to reduce income inequality between Black and white households in the bottom half of the distribution.[2] In a typical year, the EITC has been shown to reduce income inequality by 5 to 10 percent. It also benefits low-income single mothers by increasing their checking and savings account balances and helping them reduce their debt.

Any discussion of expanding the EITC program will need to take into account the EITC’s effects on labor force participation. Changes or expansions could have distinct consequences for women, racial minorities and households with children as well as lasting effects on poverty and income gaps in the U.S.

Notes

- The Annual Social and Economic Supplement surveys over 75,000 households each year, asking them questions on work, income, taxes, poverty, migration, disability, health insurance, veteran status and more.

- See “The EITC and Racial Income Inequality,” by Bradley Hardy, Charles Hokayem and James Ziliak, WorkRise, Sept. 29, 2022. They found that the EITC reduced Black–white income inequality at the 25th and 50th percentile income levels but had no demonstrated improvement at the 10th percentile.

About the authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.