Hotter summer days heat up Texans but chill the state economy

As Fed monetary policy tightening extended through the past summer and some economic activity slowed, policymakers confronted a question perhaps worthy of a climatologist: How did record heat across Texas combine with economic policy to affect the overall economy?

The Federal Open Market Committee’s tightening cycle began in March 2022 with the benchmark federal funds rate rising more than 5 percentage points since then in a bid to slow economic growth and contain inflation. More recently, the impact of the sometimes-relentless summer 2023 heat appears to have depressed the ability of some industries to supply goods and damped consumer demand, especially for certain services.

Analyses drawing on data from 2000–22 indicate Texas is especially vulnerable to hotter summers. For every 1-degree increase in average summer temperature, Texas annual nominal GDP growth slows 0.4 percentage points.

With this year's summer temperatures 2.5 degrees above the post-2000 average, estimates for Texas suggest, all else equal, the summer heat could have reduced annual nominal GDP growth by 1 percentage point for 2023, or about $24 billion. Other calculations suggest a somewhat lesser impact of nearly $10 billion in real (inflation-adjusted) GDP, about 0.5 percent of annual output.

The impact of an increase in summer temperatures on Texas GDP growth is twice as pronounced as the change in the rest of the U.S. because summers are generally hotter relative to the rest of the country. At the same time, the effect of rising summer temperatures on job growth is more subtle, though the effects vary widely across sectors. As climate change’s effects intensify over the next decade, heat waves will become more commonplace and severe, and Texans will need to adapt.

Employers report pronounced summer impact

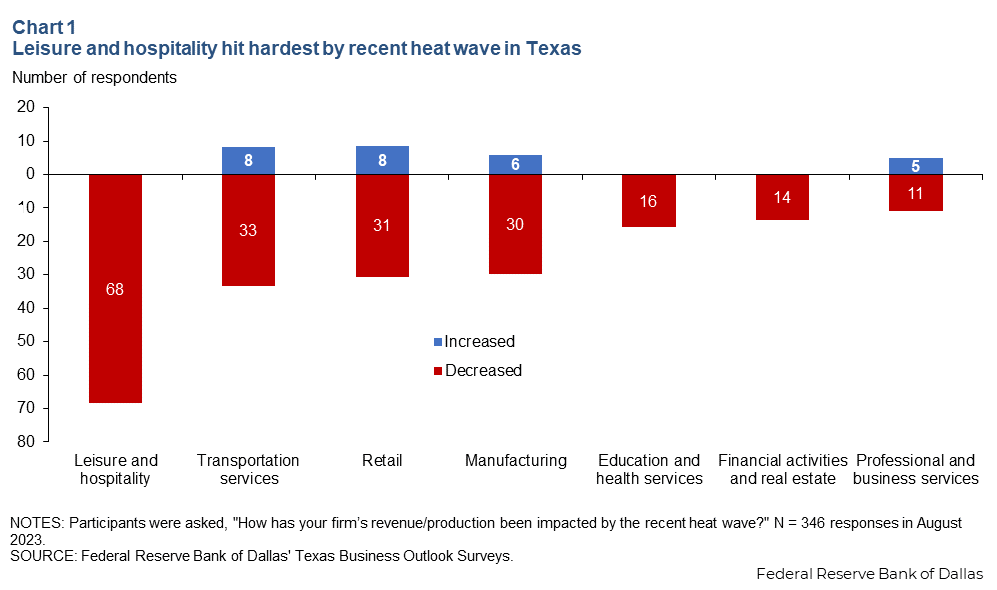

The 2023 Texas summer set records from Houston to Dallas and westward to El Paso. A quarter of respondents to the Dallas Fed’s Texas Business Outlook Surveys (TBOS) in August reported lower revenue or lower production due to the heat. The impact, while most pronounced in leisure and hospitality, was widely reported across sectors (Chart 1).

The heat wave led to lower customer demand, less activity in temperature-sensitive worksites and reduced labor productivity, which in turn drove revenue and production declines, TBOS respondents indicated. Overall, the heat affected a higher share of manufacturing firms than service sector firms.

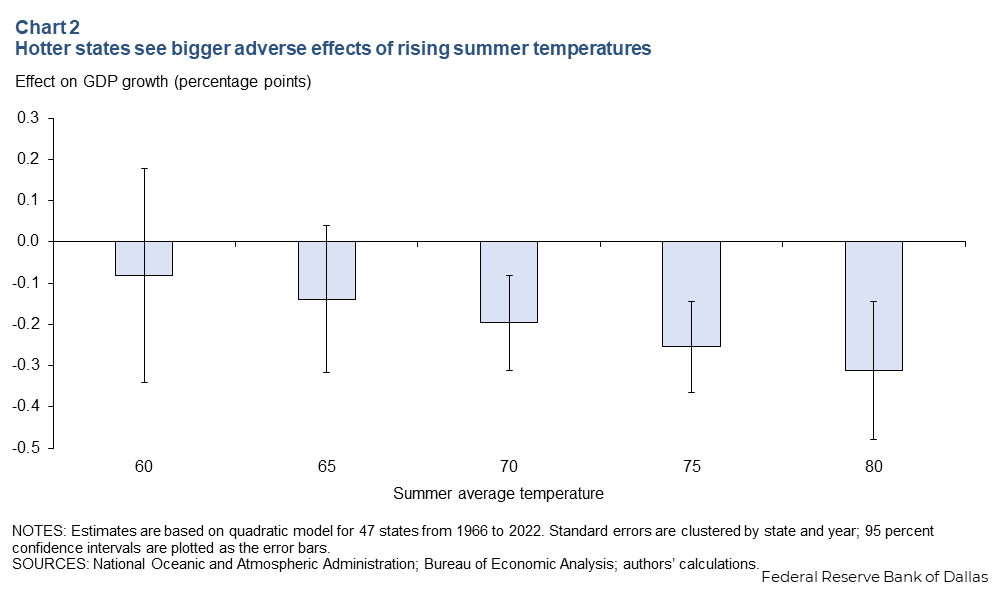

Analysis on data since the mid-1960s indicates an increase in summer temperatures leads to slower output growth. However, the effect is nonlinear: The negative impact on nominal GDP growth is not uniform across temperatures. The higher the average summer temperature, the greater the impact of additional temperature increases, likely due to more adverse effects on health and productivity (Chart 2).

On the other hand, a rise in temperatures in winter, fall and spring should present fewer challenges and could even potentially help growth.

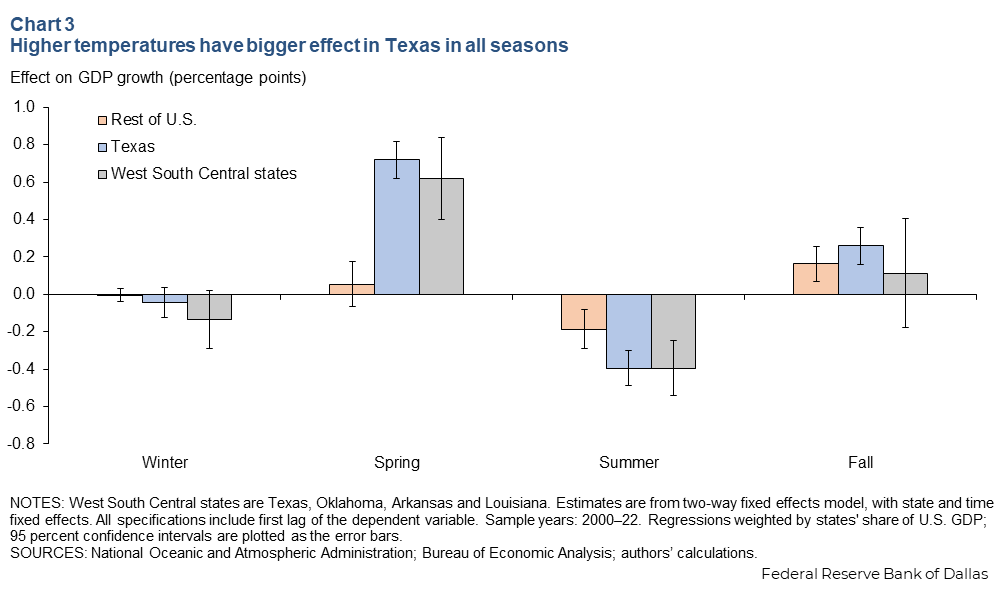

For Texas, warmer temperatures in spring and fall seasons are a relative boost to output and stand in contrast to the summer drag. The summer impact on Texas GDP average annual growth of 5.7 percent amounts to about a 7.1 percent drag on the topline figure. The impact of higher summer temperatures in Texas is comparable to the average effect observed in the West South Central region of the country—Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas and Louisiana (Chart 3).

Seasonal considerations play into GDP impact

Outside of the summer, higher spring temperatures seem to spur economic activity, particularly in Texas and neighboring states with mostly temperate winters. Among the plausible explanations, the agricultural industry gains from warmer conditions, which enable farmers to begin planting earlier in the season. Additionally, the real estate market, which typically experiences stronger activity during spring, may perform better with early warmth.

The impact of a rise in fall temperatures is also beneficial, though not as substantially as in spring. The growth effects of temperature fluctuations in winter are small and insignificant.

It is also important to note that examining the increase in summer temperature alone could overstate temperature’s adverse effect on growth. Generally, a rise in summer temperatures may be accompanied by a similar increase in winter, spring and fall temperatures. Given that a temperature rise in spring and fall positively affects growth, a simultaneous evenly distributed increase in temperatures across all seasons would, in fact, have a small net positive effect on growth.

Greater warmth across U.S. changes behaviors

U.S. temperatures have risen 0.17 degrees per decade since 1901, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. The pace has accelerated since the 1970s, with temperatures increasing 0.32 to 0.55 degrees per decade.

Winters, meanwhile, haven’t been quite as cold since 1896. Winter temperatures nationwide are up 3 degrees compared with a 1.5-degree rise in the summer. As temperatures continue to increase, historical data on temperatures also reveal a pattern of increasing severity and frequency of heat waves. The average length of heat waves nearly tripled from 24 days in the 1960s to 73 days in 2020.

One study using older data found that a 1-degree increase in average summer temperature is associated with a 0.15–0.25-percentage-point reduction in state output growth. This effect was stronger in states with relatively high temperatures, mainly Southern states.

Anecdotally, everyday behavior in Texas changed during the summer of 2023 as the heat bore down. “The extreme heat definitely kept people home. That, coupled with the economy and people leaving Texas to go on vacation in cooler climates like Colorado and Utah, also provides a decrease in revenue,” said a TBOS respondent in the restaurant industry. Theme parks Schlitterbahn, in Central Texas, and SeaWorld, in South Texas, both made public statements citing the heat for disappointing consumer activity at their attractions.

Temperature affects employment only moderately

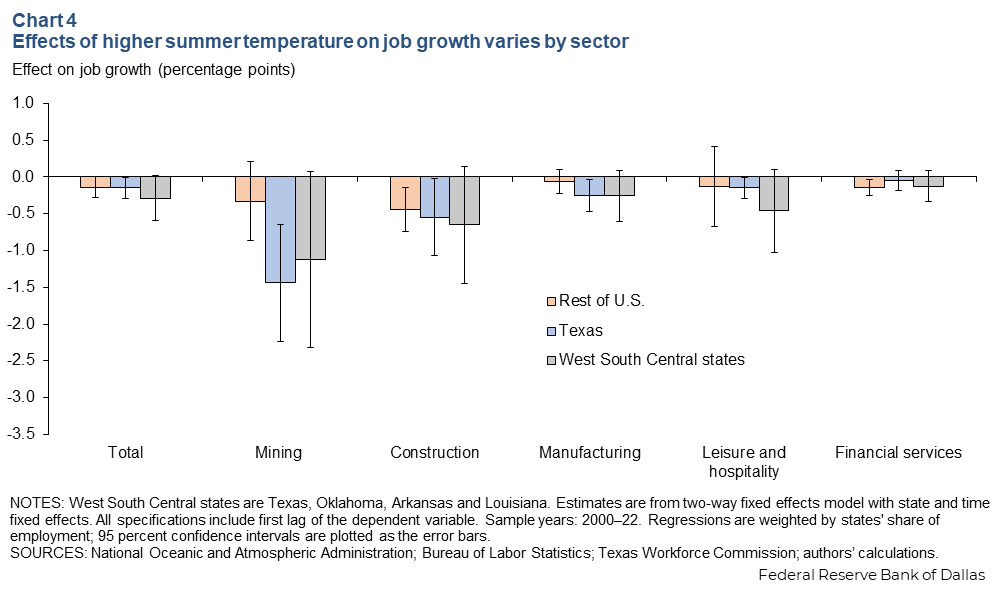

The effect of rising summer temperatures on job growth is another potential concern. However, unlike the notable GDP growth changes, the impact on employment growth is more subdued. Data show a 1-degree increase in average summer temperature reduces annual Texas employment growth by 0.15 percentage points, equivalent to a 7.5 percent decline in Texas’ average annual long-term 2 percent growth rate (Chart 4).

The effect of a 1-degree rise in summer temperature on employment growth in Texas is similar to the rest of the U.S., where the marginal effect is 0.14 percentage points.

The relatively smaller impact on employment may be because even though high temperatures harm productivity growth, companies don’t immediately reduce their workforce. After all, high temperatures are transitory. Firms might choose to adjust working hours or implement other short-term measures to manage the heat while retaining workers. This reflects the expense and difficulty of hiring and training new workers.

Employment effects vary across sectors

While the estimated overall employment growth effects are relatively muted, some industries are notably affected. Sectors such as mining, construction, manufacturing, leisure and hospitality, and financial services seem to experience more adverse employment effects.

The mining sector in Texas appears especially sensitive to temperature fluctuations. A 1-degree increase in average summer temperature leads to a 1.4-percentage-point decline in employment growth in the mining sector, mainly oil and gas in Texas. By comparison, this sectoral effect is 0.3 percentage points in the rest of the U.S.

But there is a degree of statistical imprecision with such estimates. The reduction in mining job growth, for example, could be as low as 0.6 percentage points or as high as 3.2 percentage point.

A possible reason for the notable effect is that the mining sector is one of the most heat-exposed sectors, with much of the oil and gas extraction work performed outdoors. Equipment failures caused by extreme heat can lead to production cuts.

The data also show that much of the negative summer effects could be due to the shifting of activity from the summer to spring when temperatures are cooler. Moreover, the impact on Texas' mining sector appears reasonable when compared with mining’s typically high fluctuations in job growth.

Similar to mining, the construction industry, heavily reliant on manual labor, also faces challenges due to the intense heat. A 1-degree rise in the already hot summer leads to a 0.5-percentage-point decline in Texas’ construction employment growth, an effect that is larger than the 0.4-percentage-point reduction for the rest of the U.S.

Job growth in the manufacturing sector falls by 0.25 percentage points for each 1-degree increase. This decline is less pronounced compared with the construction sector since manufacturing operations are primarily conducted indoors. Despite this, factories still face issues such as equipment failures and a drop in worker productivity during hotter summers since many plants are not air conditioned.

As expected, activity declines in the leisure and hospitality sector, which is sensitive to hot weather. In Texas, job growth in leisure and hospitality slows by 0.15 percentage points for each 1-degree rise in temperature, a rate similar to the rest of the U.S.

Determining drivers of negative growth effects

Many of the adverse effects of rising temperatures on economic growth stem from their negative impact on health and productivity. Extreme weather conditions, both hot and cold, result in increased mortality rates. For example, when summer temperatures exceed 90 degrees, mortality rates spike by 2 percent, affecting labor supply and overall productivity.

Negative productivity effects have been previously reported using data across countries, identifying a hump-shaped correlation between a country's per capita GDP and its annual average temperature.

Another way temperature affects growth is by impacting worker availability. One study found that hours worked decline significantly when daily maximum temperatures rise above 85 degrees in the U.S. Using county-level data, another study found that per capita income drops by 1.7 percent for each 1.8 degree rise in temperature above 59.

Besides diminished labor supply and productivity, rising temperatures also affect growth through lower agricultural yields and disruptions in electricity supply. The adverse economic effects of rising temperatures could be further amplified by some additional negative social effects, such as the contribution to increased crime rates.

Texas can adapt to hotter summers

As climate change’s effects intensify over the next decades, heat waves will become more commonplace and severe. A report by Texas A&M University’s Office of the Texas State Climatologist projects average Texas temperatures in 2036 will be 3 degrees warmer than the average temperature from 1950 to 1999 and 1.8 degrees warmer than the 1991–2020 average.

The number of 100-degree days is expected to almost double by 2036 compared with 2001–20, especially in urban areas.

However, the economy can adapt. For example, theme parks such as Six Flags in Arlington are implementing new ways to protect customers from the heat by adding cabanas to provide additional shade. Manufacturers are also considering longer-term production changes to mitigate the heat.

Communities may also adopt new technology to become more sustainable, create walkable neighborhoods or retrofit existing buildings to improve energy efficiency and seasonal ease of movement.