Taking the global housing market’s temperature: Is it running a fever (again)?

House prices are rising rapidly—not just in the U.S., but around the world. The global increases in part reflect the pandemic response of governments and central banks, which boosted income and lowered borrowing costs through fiscal transfers and monetary policy accommodation.

This support propped up demand at a time when lockdowns aimed at curbing COVID-19 pinched housing supply.

Some lifestyle changes accelerated by the pandemic—such as work-from-home arrangements and other structural shifts impacting housing—will likely linger even after supply catches up with the recent demand surge in many international markets.

Inflation-adjusted house prices rapidly accelerate

The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas releases a quarterly time series of house prices for 25 countries. The data, starting in first quarter 1975, largely reflect the experiences of advanced economies.

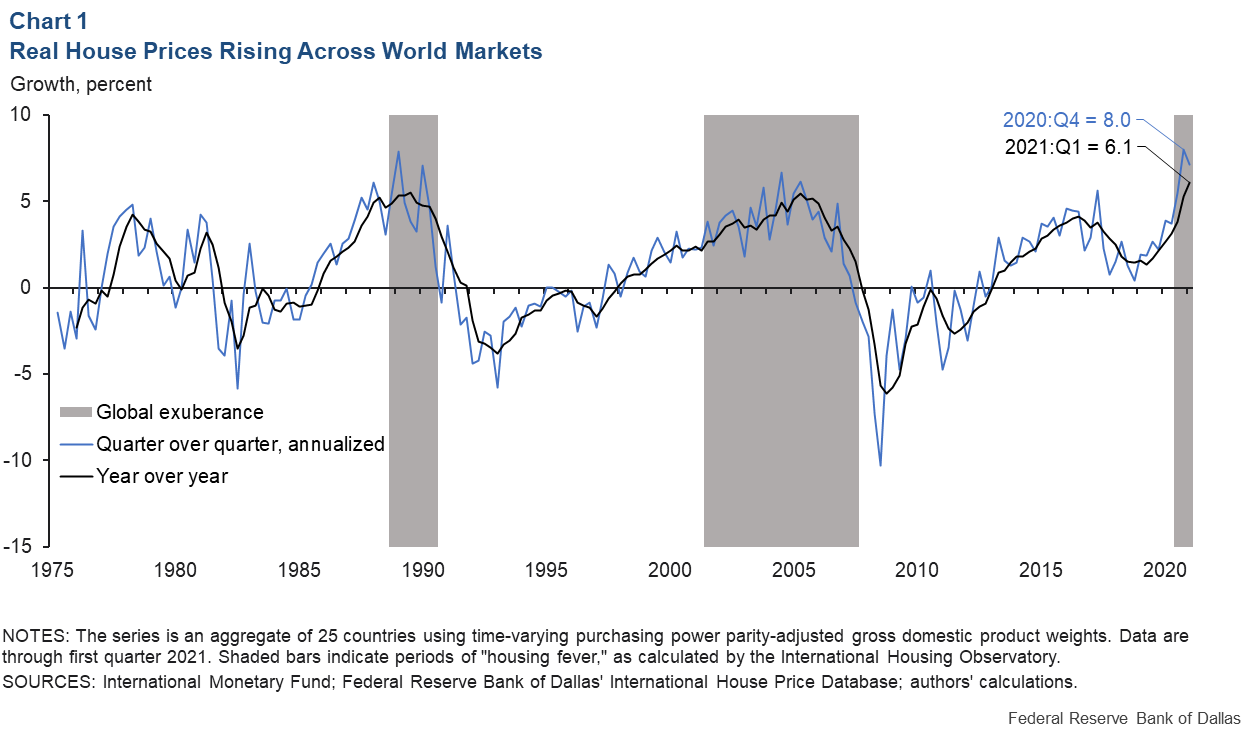

Real (inflation-adjusted) house prices around the world have risen rapidly during the pandemic, the data show. The gross domestic product-weighted aggregate of house prices exceeded 8.0 percent quarter-over-quarter growth (annualized rate) in fourth quarter 2020 and 6.1 percent year-over-year in first quarter 2021. Both readings are highs in the historical series (Chart 1).

The recent house price acceleration has outpaced gains in previous global booms in the late 1980s and even in the early 2000s, 2000s (before the 2007–09 global financial crisis). Large house price rises have again become as widespread as they were in the 2000s run-up, data show.

The current trajectory prompts the question: Do markets face the prospect of a housing bubble once again? Alternatively, are these price increases in step with housing market fundamentals?

Taking the temperature of international housing markets

A joint project between the Dallas Fed and the Lancaster University Management School in the U.K. employs statistical techniques for monitoring international housing markets.

These statistical techniques differ from traditional model-based approaches of evaluating whether house prices are out of step with fundamentals. This procedure is akin to taking the temperature of the housing market.

Rather than explicitly modeling the demand and supply determinants of house prices, we empirically test and identify breaks in the time series toward explosive behavior—what we call “housing fever.” We would expect to see such explosive behavior if house prices were becoming unhinged, showing signs of a bubble.

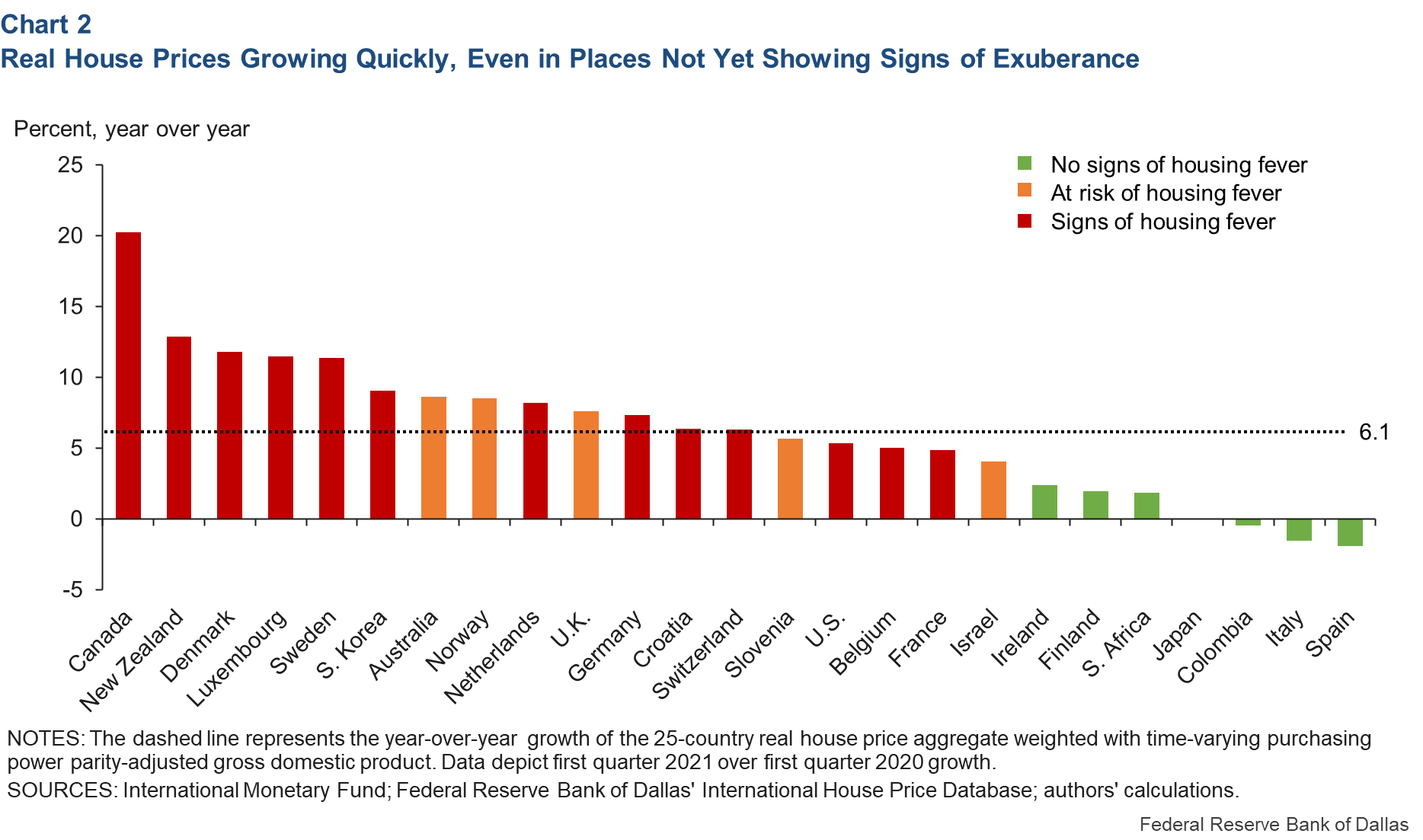

Drawing on historical data and with the benefit of these new statistical tools, we evaluate what has happened to global house prices during the pandemic. It appears that many countries are running fevers—the U.S., Canada, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Denmark, Sweden, Croatia, Switzerland, South Korea and New Zealand.

Moreover, even in several countries that have not yet developed signs of a housing fever, very significant price acceleration has appeared relative to first quarter 2020—such as in the U.K., Slovenia, Norway, Israel and Australia (Chart 2).

Housing market temperature rose during pandemic

In the same way that a fever indicates an illness and is not itself a diagnosis, we need to dive deeper into the set of countries running hot to assess what’s going on. We find that the behavior of housing during this recession has been different than during previous house price run-ups.

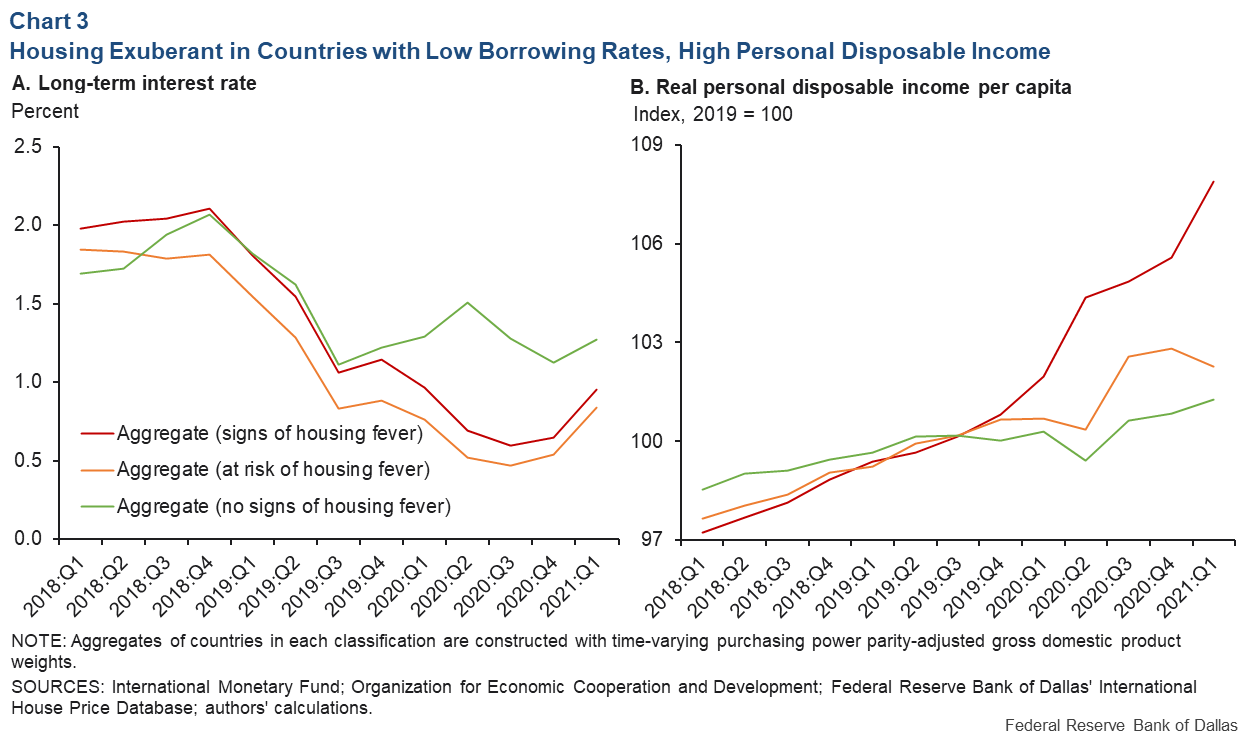

A clearer pattern emerges when countries are grouped by those showing signs of housing fever and those that are not (Chart 3).

Countries experiencing explosive house price appreciation have experienced a significant degree of fiscal and monetary stimulus in response to the pandemic. The practical implication is that large increases in disposable income occurred at a time when pandemic-related mobility restrictions severely restrained opportunities to consume. This boost to disposable income—in tandem with low interest rates—likely helped drive up household savings that were then deployed toward higher-yielding assets such as housing, the supply of which was constrained by materials and labor issues.

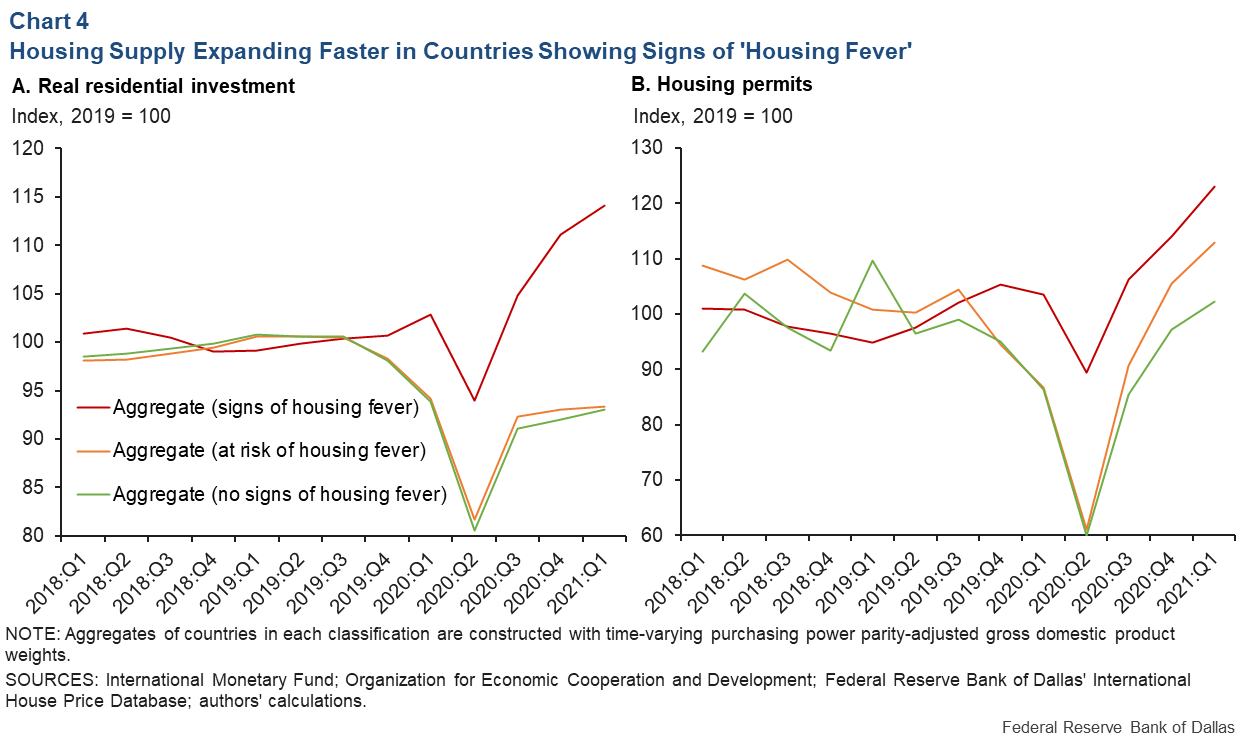

There are signs that housing supply is starting to respond to this increased demand as restrictions ease and vaccination rates rise. As inflation-adjusted residential investment starts to grow in countries showing signs of fever, the number of building permits issued has also bounced back (Chart 4).

The benign view is that housing demand outstripping housing supply during 2020 largely explains the ongoing episode of global housing fever. To the extent that supply catches up with demand over time as mobility restrictions are lifted and economies normalize, housing markets will cool on their own without a major correction. Following on our health analogy, this benign prognosis would suggest that the immune response of the economy is taking hold.

Uncertainty and trends to watch

However, other trends associated with the data still carry great uncertainty. There is a risk of future waves of COVID-19 infection if new variants emerge and outflank vaccines. It is also possible that pandemic-accelerated lifestyle changes, such as work-from-home, will persist.

Diagnosing the current situation requires watching all available indicators of housing exuberance. For now, it appears that fundamental supply-and-demand forces are contributing to the historically high house price appreciation seen in the data. If this upward pressure persists, it may indicate not all is well, requiring policymakers’ attentiveness and—if necessary—an appropriate response to return markets to a more sustainable level aligned with fundamentals.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.