Pandemic Unemployment Benefits Provided Much-Needed Fiscal Support

Notable among the unprecedented federal stimulus measures implemented in response to COVID-19 was an additional $600 per week in jobless benefits for furloughed and laid-off workers.

The supplemental payment came on top of existing unemployment payments, with the total amount per recipient varying widely across states, according to U.S. Department of Labor data.

The additional funds were contained in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act and its Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) program.

In per-capita terms, Texas disbursed a smaller amount than the national average through July, reflecting both the state’s lower unemployment rate and a smaller share of the labor force filing unemployment insurance claims. Consequently, Texas received relatively less fiscal stimulus from the FPUC program than many other states.

Unprecedented Fiscal Stimulus

As state and local governments across the U.S. issued stay-at-home orders in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the resulting shutdown and associated plunge in mobility led to a historic contraction in economic activity; this contributed to unprecedented job losses and soaring unemployment.

Texas lost 1.3 million jobs in April, as payroll employment contracted at a historic pace of nearly 11.0 percent, and the unemployment rate reached 13.5 percent. Contraction at the national level was even more pronounced; U.S. employment plunged 13.8 percent in April and the unemployment rate rose to 14.7 percent.

To limit the economic fallout, Congress passed the CARES Act, a package of unprecedented relief measures. In addition to providing loans to struggling businesses and funding for public health measures to contain the pandemic, the $2 trillion CARES Act economic package included $290 billion in stimulus checks sent directly to taxpayers and an additional $260 billion in federal funding to expand unemployment insurance benefits.

Most importantly, the CARES Act created the FPUC program to substantially increase benefit amounts under the existing unemployment insurance system—a program providing benefits designed to replace roughly 50 percent of past wages for eligible recipients.

Regular state benefits are capped, and maximum weekly benefit amounts vary widely across states, ranging from $235 in Mississippi to $823 in Massachusetts. Regular weekly state unemployment insurance benefits in Texas are capped at $521.[1] Regular state benefits last up to 26 weeks in most states. An extended benefits program, funded equally by the state and the federal governments, provides benefits for an additional 13 to 20 weeks in states facing high unemployment.

It is widely believed that, along with other stimulus measures in the CARES Act, the additional weekly $600 unemployment payments threw a lifeline to an economy in freefall as the pandemic struck. Unlike regular state unemployment insurance payments, which are tied to prior wages, FPUC benefits were a monthly lump sum to top up regular benefits. These were, therefore, especially generous to low-wage workers who needed the most help.

The median replacement rates from jobless benefits with FPUC rose to 153 percent in Texas—substantially higher than the average replacement rate of 52 percent from the regular state unemployment insurance program.[2]

Receiving Less Per Capita

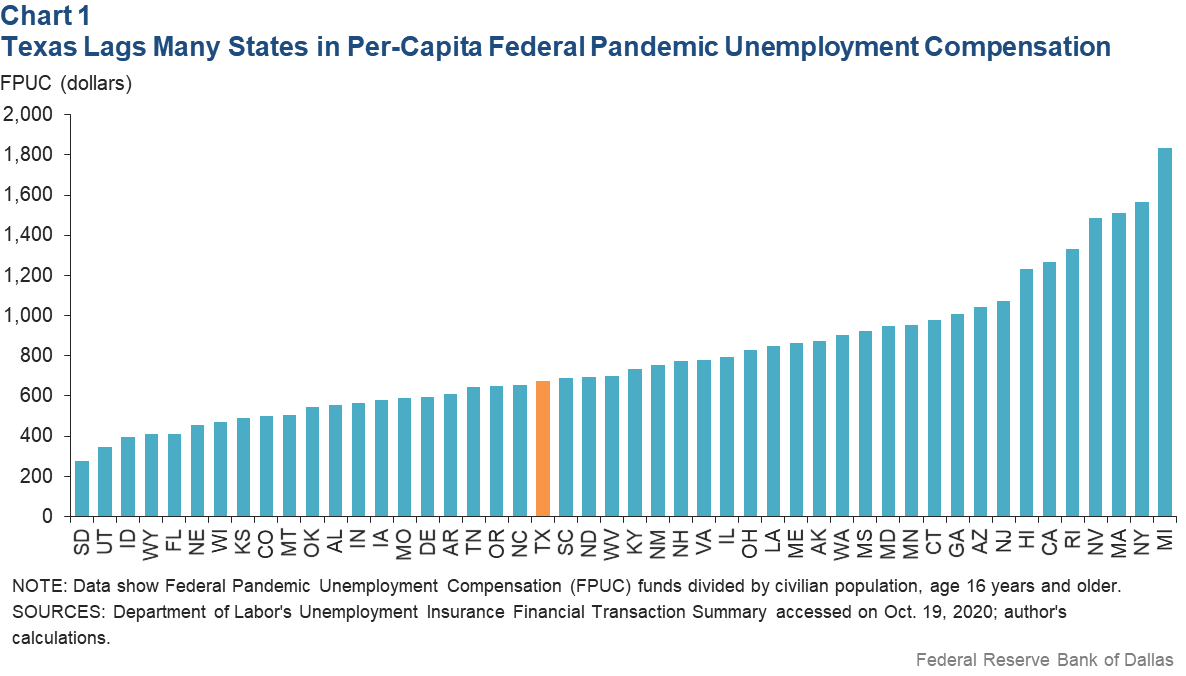

Benefit payments through the FPUC program differed widely across states, U.S. Department of Labor data show.[3] Texas received nearly $15 billion of the $224 billion the federal government sent to states, based on available data. Per-capita FPUC payments through July in Texas were $675—25 percent lower than the national average of $900.

Per-capita benefit payments ranged from $275 in South Dakota to $1,834 in Michigan, with Texas among the bottom half of the states ranked by the size of per-capita federal assistance through FPUC (Chart 1). The wide variation in FPUC payments per-capita reflects differences in the severity of the downturn across states. States with higher unemployment received more federal funding and made more payments to jobless recipients.

Besides supplementing weekly unemployment benefits under the regular state program, the FPUC program also extended the $600 additional payments to beneficiaries of two other programs the CARES Act created to expand eligibility and extend benefit duration.

The Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation program, which expires at year-end, allowed 13 additional weeks of unemployment benefits for individuals exhausting their regular state benefits.[4] Counting the total number of weeks under regular and special pandemic programs, Texans can receive jobless benefits for up to 59 weeks.

The CARES Act also created the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program, which expanded eligibility for unemployment insurance benefits to the self-employed, including independent contractors and gig economy workers and those with limited work history who typically would not qualify for assistance. The program provides benefits to these individuals for up to 39 weeks until year-end.

Of the 1.12 million Texans claiming jobless benefits in the week ended Sept. 26, nearly 72 percent received benefits under the regular state program; the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program accounted for 26 percent of total claimants and the Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation program was responsible for 3 percent.

Fewer Jobless in Texas

Lower FPUC payments in Texas were for the most part due to the state’s lower unemployment rate relative to the nation. Not surprisingly, Texas also consistently had a lower share of the labor force receiving jobless benefits. Counting gig workers and other self-employed, who typically do not qualify but were newly eligible, the Texas–U.S. gap in the share of labor force receiving jobless benefits widened, suggesting that a relatively smaller share of such workers received benefits in Texas.

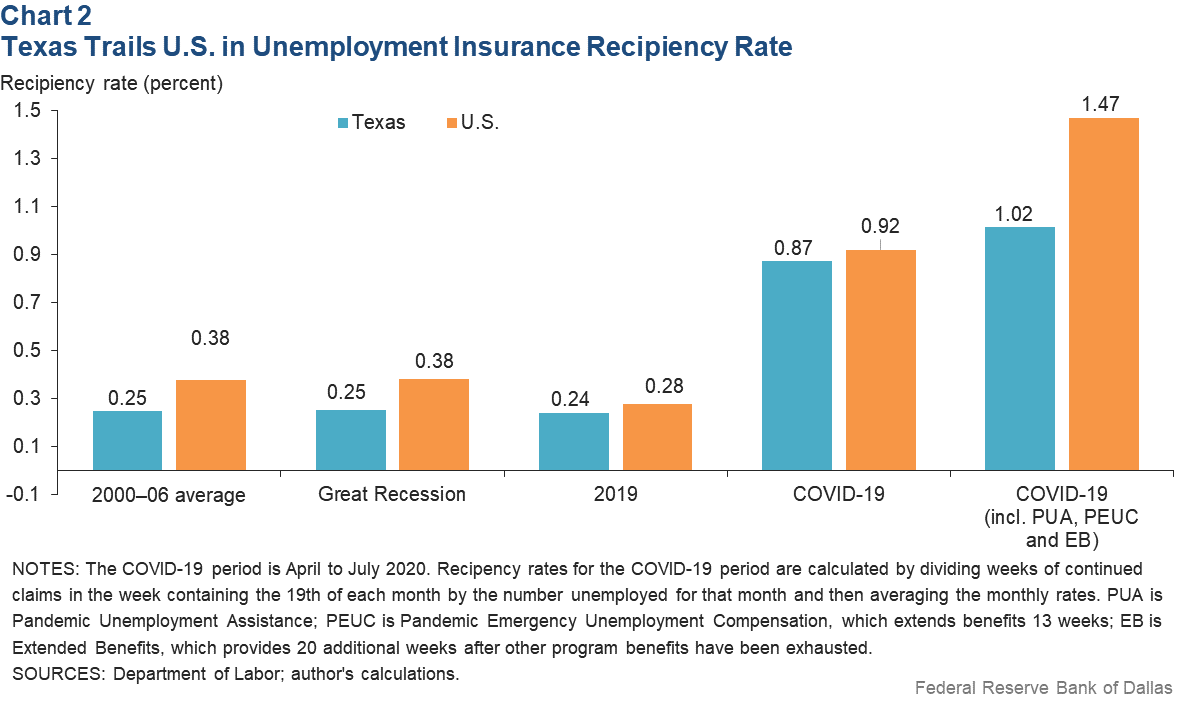

To be sure, Texas has fewer workers receiving jobless benefits relative to the nation because the unemployment rate did not rise as much. However, even among the unemployed, fewer in Texas received jobless benefits (Chart 2).

Counting just the insured unemployed under regular state programs, the recipiency rate jumped during the most recent downturn in both Texas and the U.S., thanks to more-generous benefits and expanded coverage with few or no job search requirements. Average recipiency rates from April to July remained slightly lower in Texas, though the gap relative to the nation narrowed significantly when compared with the Great Recession. In fact, Texas’ recipiency rate in June and July exceeded the national rate.

Nonetheless, including claims filed under the program for the self-employed, Texas’ recipiency rate continued to lag the nation by a wide margin. Notably, including the claims under the program for independent contractors and gig workers, total claims exceeded the number of unemployed. This was because like regular recipients, many of the contractor recipients may be partially unemployed or out of the labor force due to reasons related to the pandemic and, thus, aren’t counted among the unemployed.

Rates Across States

Unemployment insurance recipiency rates can differ across states for many reasons. First, some who are eligible do not apply for benefits. Second, not all unemployed are eligible; only those who lose jobs through no fault of their own qualify for benefits. Those simply quitting jobs or getting fired are ineligible.

Finally, to be eligible, the unemployed must also have worked and earned sufficient wages prior to their last job before filing an unemployment claim. Workers also must be available to work and actively looking for a job in order to remain eligible. However, several states including Texas waived work search requirements during the pandemic.

Like most states, multiple factors limit eligibility in Texas. For example, workers applying for benefits must have wages in at least two quarters of the base period, which consists of four of the last five quarters before filing an application.

To qualify, an applicant must earn at least $2,516 in the base period. Partially employed workers in Texas still on the job but whose hours have been cut must earn no more than 125 percent of the weekly benefit amount calculated, assuming total unemployment.

Bureau of Labor Statistics 2018 data on the characteristics of unemployment insurance recipients show that the take-up rate is lower for nonunion workers, younger workers and those without a college degree. A higher prevalence of all three of these characteristics in Texas relative to the U.S. also contributes to lower unemployment insurance recipiency rates in Texas.[5]

Unemployment Benefits, Cost

Fewer unemployed individuals receiving jobless benefits may be desirable if the states are paying for those benefits, particularly if the labor market is healthy and the economy is operating near full employment. Prior research indicates that overly generous unemployment benefits can damp job search efforts and contribute to higher unemployment and longer jobless spells by raising a worker’s asking wage at which job offers would be worth accepting.

With many workers unwilling to accept job offers and expecting higher wages, firms can face difficulty hiring and filling job vacancies. Some businesses responding to special questions from the Texas Business Outlook Surveys cited generous unemployment benefits as an impediment to recalling furloughed workers when the economy reopened in the state after COVID-19 stay-at-home orders expired April 30.

While the moral hazard of reduced job search effort could be important when jobs are plentiful, it is less of a concern when the economy is in the doldrums. Those additional unemployment benefits from the FPUC program likely prevented an even-steeper drop in consumer spending by providing much-needed liquidity to unemployed individuals when there were few available jobs.

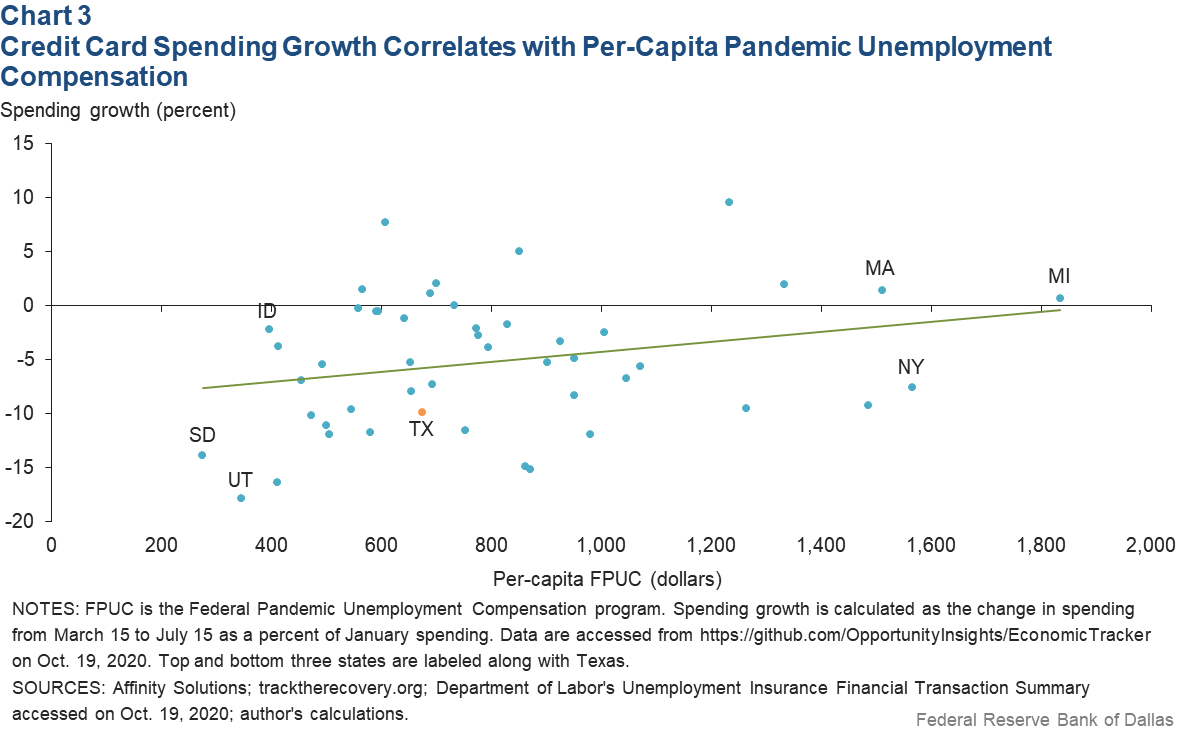

Plotting the correlation between a change in credit card spending from March to July and per-capita FPUC payments, Chart 3 shows that states receiving higher per-capita FPUC funds, such as Michigan and Massachusetts, also tended to experience smaller drops in overall credit card spending. In fact, credit card spending from March to July rose in high FPUC states. On the other hand, credit card spending fell off sharply in low FPUC states, such as South Dakota and Utah.

The correlation between FPUC payments and credit card spending is even stronger among low-income individuals. The possibility that FPUC payments boosted overall spending underscores their importance as a source of fiscal stimulus to states.

A positive effect on local spending also likely helped alleviate a potentially sharper decline in sales tax revenues. Recent evidence drawn from the Great Recession suggests that more-generous unemployment insurance benefits helped reduce delinquency rates among the unemployed, prevented foreclosures and contributed to housing market stability during the last downturn.[6] Thus, the aggregate economic stabilization benefits of FPUC payments potentially exceed the direct benefits to the unemployed.

Thanks to such positive spillovers, the FPUC program helped kick-start the recovery as early as May, though the road to full recovery remains long and bumpy. As of September, Texas employment remained 6.6 percent below its February level, and the unemployment rate was 8.3 percent—a rate last seen during the Great Recession.

Meanwhile, the $600 FPUC payments ended on July 31, and Congress has been unable to agree on an economic relief package to restore additional benefits. Executive action from the president authorized $300 in additional benefits drawn from $44 billion originally earmarked for federal disaster relief funding. This stop-gap measure was expected to provide relief for no more than six weeks. The $300 benefit ended in Texas on Sept. 5, potentially slowing the pace of the economic recovery from COVID-19.

Notes

- A handful of states, mainly in the south, end state benefits earlier; Florida and North Carolina have the shortest duration of 12 weeks. Considering both the maximum weekly benefit amount and maximum number of weeks for which benefits are provided, the maximum possible benefit in a period of unemployment ranges from $3,300 in Florida to $21,398 in Massachusetts, with Texas at $13,546.

- See “U.S. Unemployment Insurance Replacement Rates During the Pandemic,” by Peter Ganong, Pascal J. Noel and Joseph S. Vavra, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper no. 27216, May 2020.

- Because Pennsylvania and Vermont had incomplete data for July and the District of Columbia was an outlier, analysis was restricted to 48 states.

- The Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation program is similar in spirit to Emergency Unemployment Compensation programs created by Congress during times of previous national recessions to extend expiring regular unemployment benefits. The last such emergency program was in response to the Great Recession in 2008 and expired in 2013 after multiple extensions.

- Higher prevalence of undocumented workers in Texas who count among the unemployed but are not eligible for unemployment insurance benefits also contributes to a lower recipiency rate.

- See “Unemployment Insurance as a Housing Market Stabilizer,” by Joanne W. Hsu, David A. Matsa and Brian T. Melzer, American Economic Review, vol. 108, no. 1, 2018, pp. 49–81.

About the Author

Anil Kumar

Kumar is an economic policy advisor and senior economist in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2020/swe2004.