Economy's essential early care and education industry recovering but still faces labor shortfall

Child care is essential for many working parents to remain in the labor force, especially mothers (and in particular mothers of color). This was made even more apparent during the pandemic when the early care and education (ECE) industry took a hard hit. Employment in the industry fell sharply by 47 percent at the beginning of the pandemic, and one-third of child care centers remained closed a year into the pandemic. Now that two years have passed since the onset of COVID-19 in the United States, to what extent has the ECE industry recovered from this initial shock?

To answer this question, we analyze monthly data on turnover rates for center-based ECE teachers from 2019 to early 2022.[1] The monthly turnover rate is the share of ECE workers leaving their jobs each month. After a sharp rise during the initial months of the pandemic, we found that the monthly turnover rate of ECE employees quickly returned to its prepandemic level and has largely remained there since. However, this masks two important facts:

- First, ECE teachers were more likely to transition into low-skill service jobs in the first year of the pandemic.

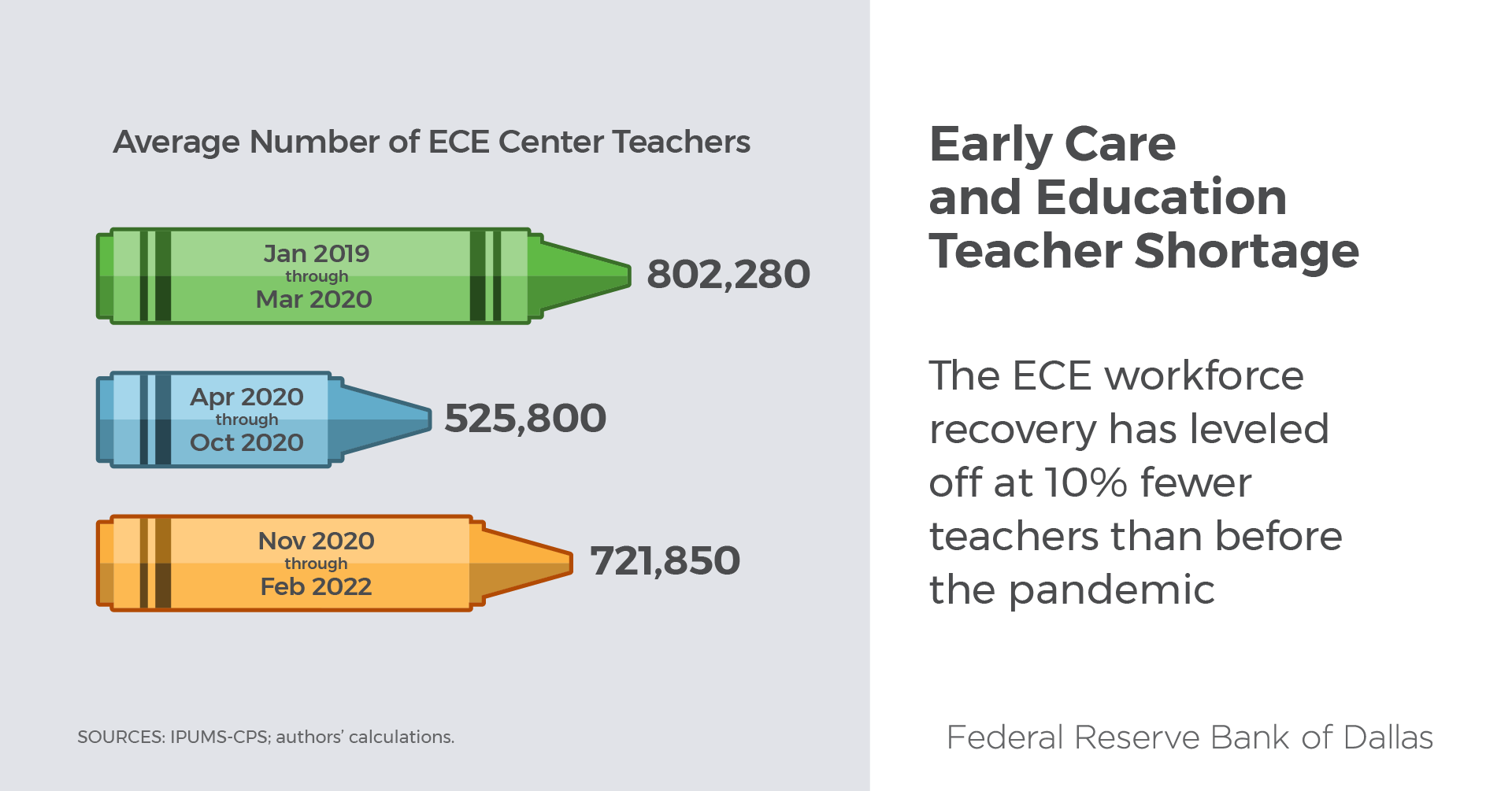

- Second, the recovery of the ECE workforce has stagnated since the end of 2020. The number of center-based ECE teachers leveled off at roughly 80,000 fewer teachers than before the pandemic.

As our two-part series will show, the ECE industry continues to experience great disruption, both for teachers and staff and the families they serve. Our analysis highlights key statistics that help understand this volatility. It will be important to address these factors in future policies and funding opportunities in order to stabilize this industry.

ECE industry churn returns to prepandemic levels

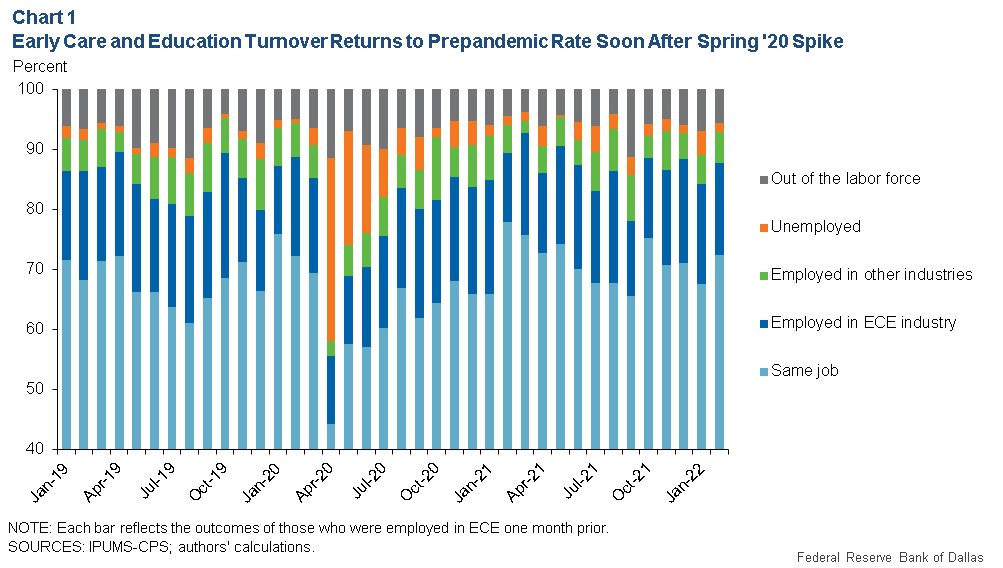

Like many workers providing in-person services, ECE workers faced higher rates of unemployment early in the pandemic than they did prior to it. Chart 1 shows the labor force status of an average ECE center worker. For example, the orange areas indicate the probability of an ECE teacher being unemployed the following month. The light blue areas show the likelihood of an ECE teacher remaining in the same job one month later.

When the pandemic first struck and many child care centers closed, ECE worker unemployment spiked. One in three ECE teachers in March 2020 were unemployed a month later, and unemployment remained elevated through much of the rest of the pandemic’s first year. This contributed to an unusually high average monthly turnover rate in 2020.

After the first year of COVID-19, these metrics improved. ECE teacher unemployment looks more similar to prepandemic levels today when we expand the timeline to early 2022. In 2019, nearly 2 percent of ECE teachers became unemployed each month. After the first year of the pandemic, the share came down to just over 2 percent. Similarly, the monthly turnover rate has returned to prepandemic levels. On average, the turnover rate was 32 percent prepandemic and 29 percent between January 2021 and February 2022.

Former ECE workers often turn to occupations in education and other services

A comparison of the dark blue and green bars in Chart 1 shows that most ECE teachers who leave their jobs stay in the ECE industry. But given the set of skills these workers have, what other jobs do they tend to gravitate toward?

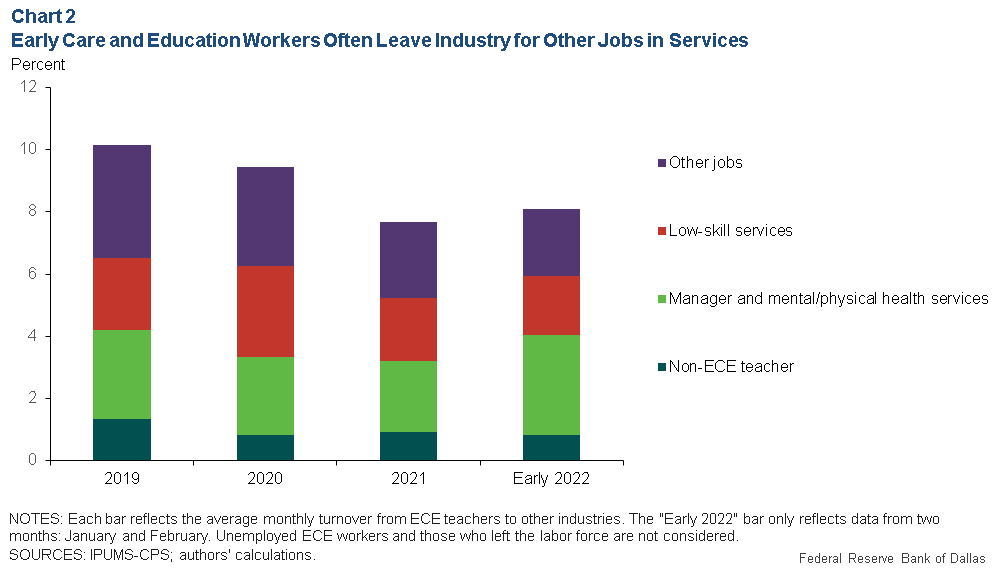

We break industries and occupations down further and find that some become teachers of other types (K–12 for example)—jobs where they can easily transfer many of their skills (Chart 2). Many go into management, where they might further their organizational experience from the ECE industry. Others end up in the physical/mental health sector which, while perhaps requiring additional credentialing, remains within the caregiving realm. Lastly, those who drift into areas without any perceivable overlap with their ECE skill sets end up in low-skill service jobs.

How did the pandemic affect the career paths of those who left the ECE industry? In the year before COVID-19, 41 percent of ECE teachers who transitioned into another job became non-ECE teachers, managers or mental/physical health workers. This percentage declined to 35 percent in the first year of the pandemic. Notably, former ECE teachers were more likely to move to low-skill service jobs during the pandemic. They accounted for 22 percent of those who left the industry in 2019 and 31 percent in 2020. However, this proved to be a temporary phenomenon, with 2021 figures returning to 2019 levels. The definition of “low-skill service” jobs and more-detailed figures are available in the technical appendix.

ECE workforce far behind full recovery

The dark blue bars in Chart 1 describe the share of former ECE teachers who remained in the industry. However, the total number of ECE teachers suffered a large loss at the beginning of the pandemic. After a period of recovery, employment growth has stagnated since the end of 2020, and the size of the workforce remains far below prepandemic levels. We find that there are roughly 80,000 fewer ECE teachers in early 2022 than before the pandemic. This is proportionate to about one in 10 ECE teachers leaving the industry. The infographic below shows the average number of ECE center teachers in the months before the pandemic, at the early stage of the pandemic and after the number of employed teachers leveled off.

Those who left and those who stayed

Our study reveals that ECE employment has not returned to prepandemic levels, and the reason remains unclear. The next article in this series will shed new light on this question by exploring demographic differences among the prepandemic and current ECE workforce. It will also track working conditions at child care centers since spring 2020, including changes in wages, hours worked and health outcomes of ECE workers. The next part of this study will help explain why some workers left the ECE industry and what this loss means for its future.

Note

- Importantly, our analysis only considers those working in child care centers and does not include those who work in home or public-school settings. We focus on center-based workers for a couple of reasons. First, nearly two-thirds of children under age five who have nonparental care during the week attend a center-based program. Second, the labor market outcomes of center- and home-based ECE workers are quite different. While important, these differences are outside the scope of our study.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.