Student Loans Part 2: Borrowing for a Future

August 2015

While rising student debt remains a source of concern in the U.S., student loans nevertheless play an important role in financing higher education. The number of student borrowers in Texas and the amount borrowed continue to climb, as shown in Part 1 of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas' analysis of student loan activity in the state. Even so, Texans have low student loan debt compared with borrowers across the U.S.

The reasons families do or do not borrow for college—and do or do not repay their loans—are complex. This follow-up report explores possible influential factors for these borrowing trends. In addition, it looks at available higher education financing tools and shows how loans can be a necessity for many. Finally, it describes circumstances that contribute to loan delinquencies. The report finds that despite growing concerns, student loans are critical in bringing higher education—and a brighter future—within reach for many.

Lower Costs, Less Borrowing in Texas

Higher education costs, which are composed of tuition and fees as well as room and board, have been rising at a slower rate the past two years nationally after skyrocketing for decades.[1] Average in–state tuition and fees at four–year public universities in Texas totaled $8,830 for the 2014–15 academic year, lower than the national average of $9,139. Adjusted for inflation, the Texas average is 9 percent higher than five years ago, and the growth ranks in the middle among the states at No. 25.

On top of tuition, students must pay for rent, food and other expenses, which often represent the largest chunk of their budget. Average room and board for four–year public universities in Texas is $8,539, compared with $9,404 across the nation.[2] Texas is more affordable in terms of cost of living and education than other states, and this could be one reason Texans have relatively low student loan debt.

Demographics Affecting Borrowing

Income and Savings Capacity

A large factor in a student's need for borrowing is personal and family resources. Although Texas higher education costs are low relative to the national average, incomes are as well. Median household income in Texas trails the U.S. average by more than $1,000, and the poverty rate is 2 percentage points higher in Texas (17.6 percent versus 15.4 percent, respectively).[3] Therefore, personal and family resources are often limited for supporting higher education.

According to a 2014 report based on online interviews with a nationally representative sample of parents, only about half with children under age 18 said they were saving for college, despite the fact that nearly 90 percent said they believe college is an important investment.[4]

The report from Sallie Mae, a leading provider of education funding, also shows that most of those who save use a mix of savings vehicles. About 36 percent of saving families use dedicated college savings vehicles such as 529 plans (29 percent), prepaid state plans (14 percent) and Coverdell Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) (13 percent). The most frequently used is still a general savings account (45 percent), which typically offers lower interest but provides Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. protection and the flexibility of using the fund for other purposes.[5]

Lower–income families are less likely to save for college and more likely than high–income families to cite inadequate income as the major barrier to saving. Because of budget constraints, low–income families may be more hesitant than wealthier families to allocate savings to programs such as 529 plans that impose penalties for noncollege withdrawals (see the box, "College Savings Vehicles in Texas").[6]

Less Borrowing, Less Schooling

Another possible explanation for Texans' lower student loan debt is that students from low-income families may opt against college or choose an inexpensive college to avoid student loan debt. Indeed, low–income students in Texas across all races and ethnicities are less likely to pursue higher education.[7]

The cost of two–year public college in Texas is at the lower end in a comparison across states.[8] Instead of going to a four–year college and amassing large student loan debt, many Texas residents, especially the economically disadvantaged, go to two–year colleges and work part time. In fall 2014, 80 percent of all freshmen attending Texas public colleges were enrolled in two–year schools.[9] More than two–thirds of two–year public college students in Texas were enrolled part time.

College Readiness and Graduation Rates

College readiness—including academic performance, knowledge and confidence to manage debt—can impact an individual’s borrowing for, enrollment in and completion of higher education. Texas' high school graduation rate ranks near the top in the nation,[10] but the state doesn't fare as well in college readiness.

Texas high school students lag behind on Preliminary SAT and National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test scores, primary indicators of college readiness. While 48 percent of high school juniors in the U.S. are considered "college ready" based on a 2014–15 composite–score benchmark, only 35 percent of Texas students are at that level.[11]

Reflecting financial constraints and readiness, college graduation rates are relatively low in Texas. The state is in the bottom third nationwide in an analysis of six–year graduation rates at four-year public colleges.[12]

The graduation rate for Texas two–year public colleges ranks in the bottom 10 percent nationwide, with 6 percent of students graduating in the two–year time frame and just over 13 percent graduating within three years.[13] Fewer than two–thirds of the students in these colleges continued at the same institution after a year.[14]

Changing Population and the Race Gap

Historically, a race/ethnicity gap in educational attainment has existed in the U.S. High school graduation rates for black and Hispanic students have steadily increased over the past decade.[15] In Texas, the rates for black and Hispanic students were the highest in the nation for the 2012–13 school year.[16],[17] Still, 13 percent of black adults and 39 percent of Hispanic adults in Texas didn't complete high school, compared with 7 percent of white adults. At the same time, 21 percent of black adults and 12 percent of Hispanic adults have at least a four–year degree, compared with 35 percent of white adults.[18]

These disparities in educational attainment will be magnified by the changing demographics of the country and of Texas in particular. Hispanics are expected to account for 60 percent of U.S. population growth from 2005 to 2050.[19] The Hispanic population is expected to surpass the non–Hispanic white population in Texas by 2020.[20] Demographic changes will continue to shape the composition of the Texas campus population: About 92 percent of first–year students enrolled in colleges in Texas are state residents.[21]

Financial Aid for College: Grants Play Small Role

The financial burden of higher education is often too great for families to carry with their own resources. About 38 percent of college funds come from parent or student income and savings.[22] The size of the funding gap depends on the availability of financial aid.[23]

Table 1 shows the composition of various types of financial aid and loans for higher education at the national level. Federal and state grants together account for about 23.5 percent of all aid in the U.S. Federal Pell Grants constitute the majority of grant aid for Texas students. However, the aggregate amount awarded has decreased the past two academic years.[24] Federal, state and private sector loans largely make up the difference.

Composition of U.S. Student Financial Aid and Loans, 2013–14

| FEDERAL AID | SHARE (%) | OTHER SOURCES | SHARE (%) |

| Federal loans | 38.6 | Institutional grants | 19.4 |

| Federal grants | 19.7 | Private and employer grants | 6.5 |

| Education tax breaks | 7.5 | State grants | 3.8 |

| Federal work–study | 0.4 | Private sector loans | 3.4 |

| State loans | 0.7 | ||

| SOURCE: Authors' calculation based on the College Board's "Trends in Student Aid 2014" report. | |||

Texas has four major, largely need–based state grant programs for qualifying students. They are the Towards EXcellence, Access and Success (TEXAS) Grant, Texas Educational Opportunity Grant (TEOG), Texas Public Education Grant (TPEG) and Tuition Equalization Grant (TEG).

The TEXAS Grant specifically prioritizes serving the neediest students—those whose expected family contributions are $4,800 and below.[25] The TEOG, TPEG and TEG programs serve students in need at a specific type of institution—public two–year colleges, public colleges or universities, and Texas private nonprofit colleges or universities, respectively. Due to budget limitations, the number of qualifying students outweighs the resources available. For instance, in 2010–11, TEOG was able to serve just 5 percent of eligible students.[26] TPEG funding comes from each public college or university's budget and is awarded at the discretion of that institution. Grants target students with the greatest financial need and serve a racially diverse population. Still, grant rules leave many students ineligible and many others underserved.

Bridging the Gap with Student Loans

Due to the large gap remaining between the cost of higher education and family resources/grants, Texans are particularly reliant on loans: 60 percent of direct aid for Texas students was in the form of loans in 2012–13, compared with 50 percent nationwide.[27] Table 2 lists several types of student loans.

Major Types of Student Loans Available for Texans

| NAME OF PROGRAM | TYPE OF AID | POTENTIAL BORROWERS |

| Perkins Loan | School–based federal loan | Undergraduate, graduate and professional students with exceptional financial need |

| Subsidized Stafford Loans (Direct Subsidized Loans) | Federal loan | Undergraduate students with financial need, with maximum eligibility period |

| Unsubsidized Stafford Loans (Direct Unsubsidized Loans) | Federal loan | Undergraduates and graduate or professional–degree students |

| Direct PLUS Loans | Federal loan | Graduate or professional–degree students and parents of dependent undergraduate students without adverse credit history |

| Direct Consolidation Loans | Federal loan | Borrowers with multiple eligible federal loans after graduation and those leaving school or dropping below half–time enrollment |

| College Access Loan | Texas state loan | For Texas residents; have good credit standing; may require cosigner |

| Texas Armed Services Scholarship Program | Texas state loan | Eligible students who are selected by a state legislator and enrolled in the Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) |

Most loans in a student's portfolio are federal Direct Loans, which are provided for under Title IV of the Higher Education Act. The federal government's predominant role in higher education is rooted in the belief that all Americans, regardless of socioeconomic background, should have access to the ladder of opportunity that a college degree can provide. Coupled with this is the idea that, to keep the U.S. competitive in an increasingly globalized world, investment in human capital is a necessity. Each year, students must file the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) based on their financial situations to be considered for federal aid in the form of loans, grants or work-study.[28] State programs and institutions may also need the FAFSA information to determine financial need.

Interest rates on federal loans are based on the type of loan and do not vary by borrowers' credit history. Only PLUS loans require a credit check or a cosigner. Although the federal government stopped guaranteeing student loans made through private lenders in July 2010, subsidized student loans from revolving loan funds controlled by educational institutions continue to be available. Nonfederal loan originations were $10 billion in the 2013–14 academic year. Private loans originated by financial institutions were $8.35 billion, accounting for only 7.9 percent of the $106 billion in total originations.[29] Typically, federal loans have favorable terms for borrowers with less–than–ideal credit histories and have more flexible repayment options than private loans.

The majority of loans provided by the state of Texas are College Access Loans (CAL), totaling $95 million for the 2012–13 school year. The CAL program, with a fixed interest rate of 4.5 percent, is available to borrowers with a minimum credit score, though loan origination fees drop with higher credit scores.[30] As Texas Higher Education Commissioner Raymund Paredes explains, this program "was established precisely to meet the needs of any student in any income category. … We have students who are middle class, or lower middle class, whose families can't pay for college education without hardship, and we don’t want to leave them out." Most of this CAL balance goes to students attending four–year public universities.

The Texas Armed Forces Scholarship Program is available only to academically distinguished students enrolled in the Reserve Officers' Training Corps program who contract to serve in the armed services upon graduation. The program offers an incentive for timely graduation and strong academic performance: If a student meets the requirements, the loans are forgiven upon graduation.

Another state program, the Texas B-On-Time Loan for residents attending two- or four-year Texas schools, ended for new students in September 2015 due to legislative repeal.[31]

A Debt or Repayment Issue?

While rising college costs are forcing many families to rely heavily on loans, debt levels alone do not explain student loan performance. The average student loan balance was lower in Texas than the nation, yet Texas ranked high among the states in serious delinquencies (the percent of loans at least 90 days past due).[32]

A recent cross–state analysis found that states with poor student loan performance do not necessarily have high tuition and fees, low levels of state financial aid or high loan balances—but they often have low credit scores and low college graduation rates.[33] Student loan borrowers who are not able to finish college are less likely than those who graduate to find well–paying jobs. They are also less likely to repay the loan on time and build good credit for future borrowing.

Thus, debt levels may be a lesser issue than paying back the student loans. To address the repayment challenges, it is important to keep students in school and working toward their degrees so they are more likely to find a well–paying job.

The Value of Higher Education

Higher education is relatively affordable in Texas. However, income disparities and lower levels of educational attainment limit individuals' ability to tap their full potential, and this could put the future economic prosperity of Texas at risk.

Student loans are a critical financial tool to bridge the gap between college costs and funds from family savings and other sources of aid. Students and their families may be reticent about college because of reports about the near–tripling of student debt levels over the past decade, uncertainty over job prospects and the possibility of student loan default.

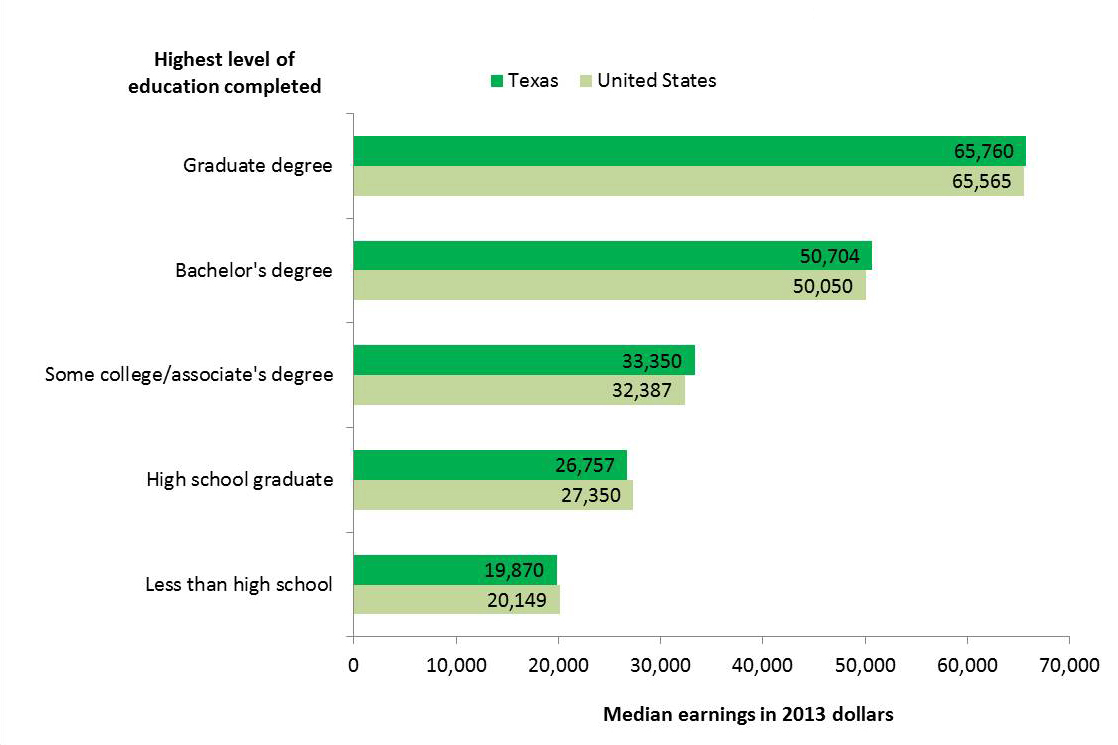

Countless studies have shown the positive relationship between one's earnings potential and education level. As illustrated in Chart 1, the biggest jump is from some college/associate's degree to bachelor's degree: A four-year degree is associated with a nearly $20,000 increase in median annual earnings for workers both in Texas and the nation.

Furthermore, annual student loan debt is less than 15 percent of annual income for graduates of most Texas programs a year after they leave school, suggesting that the financial burden from repaying student loans is typically manageable relative to income when borrowers complete the program.[34]

College is a good investment, especially for those who graduate, and a more educated population is good for Texas. Families need more guidance to navigate the complexities of paying for college and reassurance that their efforts are worth it.[35]

Chart 1

Median Earnings Increase with Education

SOURCE: American Community Survey 1–Year Estimates, 2013.

| College Savings Vehicles in Texas |

|---|

|

Texas has two major state–sponsored 529 college savings plans. The prepaid Tuition Promise Fund allows Texas families to buy tuition units at today's price to pay for the applicable portion of tuition and required fees for future attendance at Texas public colleges. Eligible beneficiaries also can apply for Match the Promise scholarships and tuition grants. The Texas College Savings Plan is the other 529 plan that allows families to save for college with tax–deferred earning growth and tax–free withdrawal for eligible college expenses. Beneficiaries can use this plan to pay for most accredited U.S. institutions and some institutions abroad. Families can manage their savings directly through this plan or seek help from a paid adviser through the LoneStar 529 Savings Plan . Texans also can invest their college savings through other state 529 plans. |

Notes

- "Trends in College Pricing," The College Board, 2014.

- National Center for Education Statistics, Table 330.20 (Average undergraduate tuition and fees and room and board rates charged for full-time students in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by control and level of institution and state or jurisdiction), Institute of Education Sciences, 2012–13.

- State and County QuickFacts derived from 2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Census Bureau.

- “How America Saves for College 2014: Sallie Mae’s National Survey of Parents with Children Under Age 18,” Ipsos Public Affairs, 2014.

- Only some states offer FDIC-insured investment choices in their 529 plans.

- “Who Benefits from the Education Saving Incentives? Income, Educational Expectations, and the Value of the 529 and Coverdell,” by Susan M. Dynarski, National Bureau of Economic Research, NBER Working Paper no. 10470, May 2004.

- “State of Student Aid and Higher Education in Texas,” by Marlena Creusere, Carla Fletcher, Kasey Klepfer and Patricia Norman, TG Research and Analytical Services, January 2015, p.17.

- See note 1.

- Enrollment tables, statewide by institution type, classification, Texas Higher Education Data , Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

- “Texas Student Groups’ Graduation Rates Outpace Peers,” Texas Education Agency News, March 19, 2015.

- “PSAT/NMSQT 2014-2015 College-Bound High School Juniors Summary Report for Texas,” The College Board.

- “College Completion: Who Graduates from College, Who Doesn’t, and Why It Matters,” The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- Texas public colleges two-year comparison data, college completion, The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- See note 7.

- ED Data Express: Data about elementary and secondary schools in the U.S. , U.S Department of Education.

- National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, Table 2 (Public high school 4-year adjusted cohort graduation rate, by race/ethnicity and selected demographics for the United States, the 50 states, and the District of Columbia: School year 2012-2013).

- "Achievement Gap Narrows as High School Graduation Rates for Minority Students Improve Faster than Rest of Nation," U.S. Department of Education, March 16, 2015.

- 2013 American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates, Census Bureau.

- “U.S. Population Projections: 2005-2050,” by Jeffrey S. Passel and D’Vera Cohn, Pew Research Center.

- “Texas Population Projections, 2010 to 2050,” by Lloyd B. Potter and Nazrul Hoque, Texas Office of the State Demographer.

- National Center for Education Statistics, Table 309.10 (Residents and migration of all first-time degree/certificate-seeking undergraduates in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by state or jurisdiction: fall 2012). After living in a state for one year, some financially independent students can obtain state residence for tuition purposes.

- See note 4, Figure 11, p. 24.

- For a more comprehensive list of all types of financial aid available, visit the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board's College for All Texans site.

- Authors’ calculations based on Federal Student Aid Center tables (Award year grant volume by school).

- Toward EXcellence, Access and Success (TEXAS) Grant Program institution guidelines for 2014–15 , Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

- “Overview: Texas Educational Opportunity Grant,” Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, 2012.

- See note 7, p. 38.

- The application can be filed at the FAFSA site.

- “Trends in Student Aid 2014,” The College Board.

- See “College Access Loan Fact Sheet,” Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

- Texas Legislative Guide, House Bill 700 .

- Loans that are 90 days late, 120 days late or severely derogatory are considered seriously delinquent. Severely derogatory loans are defined as loans that are in any stage of delinquency combined with loans assigned to government or charged off to bad debt, and reports of consumer deceased or in consumer counseling. The delinquency rate is based on the total outstanding balance.

- “State Variation of Student Loan Debt and Performance,” by Wenhua Di and Kelly D. Edmiston, April 20, 2015.

- See note 7, p.74.

- See Navigate: Exploring College and Careers program , Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

About the Authors

Wenhua Di is a senior economist in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Emily Ryder Perlmeter is a community development analyst at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.