The Texas Jagannatha

September 4, 2014 Dallas

Thank you, Ashok (Mago). I am so honored to have been invited to join Ambassador (S.) Jaishankar this evening to celebrate the U.S.–India Chamber of Commerce and its many distinguished awardees.

Mr. Ambassador, I am delighted you are here in Texas tonight. I am going to give you a few statistics in a moment that I think will make readily apparent the reason for this large audience and why so many Indian entrepreneurs and professionals come to Texas. Then I am going to give you a snapshot of where the U.S. economy is at present and what we are grappling with at the Fed. But first, with your indulgence, I want to briefly speak of the relationship between our two great countries, India and the United States.

Time to Enhance the U.S.–India Working Relationship

The logic of an enhanced strategic relationship between my country and yours is crystal clear, beginning with a harsh geopolitical reality: You live in a tough neighborhood and need us; we, in turn, need all the friends we can muster in your geographic sphere. It seems very timely that we overcome the history that has separated us and begin working more closely together.

During the Cold War, it was the view of many in the United States that India was too closely allied with the Soviet Union. American businesses that looked at India found it afflicted with the legacy of the worst of British bureaucratic administration. (The old joke was that you could never get morning tee times at any Indian golf course because the bureaucrats had locked them up at least until noon).

From an Indian perspective, America seemed too hegemonic. Attempts by U.S. companies to invest and do business in your homeland revived memories of the East India Company.

We viewed each other through the lens of the time and against a background of our own histories, with suspicion.

But the (Berlin) Wall came down, the economy has been globalized and cyberized, and new threats to security have arisen, many of them from nonstate actors or forces who operate from within failed states to inflict damage elsewhere. This is a time for like-minded people to unite and work together.

We are like-minded in that we are democracies. But tonight we celebrate something even more fundamental. My reading of India is that, like in the U.S., your country men and women are more pragmatic and business-oriented than they are ideological or inherently bureaucratic.

The recent election of Prime Minister (Narendra) Modi offers the promise of making this abundantly clear. He was, after all, the chief minister for over a decade of the Gujarat, the most probusiness state in India. And almost every U.S. business leader I know has heard of Ratan Tata’s experience when he looked to Gujarat for an alternative to the frustration of his attempt to build a new car factory in West Bengal. As I understand it, Mr. Tata went to see Minister Modi, had a handshake deal in 30 minutes, and in 14 months the new factory was up and running. That almost makes Texas look like California by comparison!

So Mr. Ambassador, we are all watching for this first prime minister born since Independence to work his probusiness, nonbureaucratic, can-do spirit upon the whole of India. It is in America’s interest for India to thrive. We wish Prime Minister Modi, the government you represent with such distinction, and the Indian nation the very best of luck.

The Texas Jagannatha

Tonight, you and I are surrounded by the smart, probusiness people of Indian heritage who have chosen to invest and operate within the most probusiness state in the United States.

I am going to throw up a few slides to quickly summarize the environment in which they operate.

Texas is a job-creating juggernaut. I pick that word deliberately, knowing it derives from the Hindi Jagannatha and is, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, a title of Krishna. Specifically, it is: “the uncouth idol of this deity at Puri in Orissa, annually dragged in procession on an enormous car,” crushing everything in its path. But Hindu or Muslim or whatever your faith, while one might consider Texans to on occasion be uncouth, there is no denying that our economy is an enormous job-creating car that enables and advances its devotees rather than crushing them. A job is the road to dignity and to the prosperity of any people, and Texas has become the most prosperous of states.

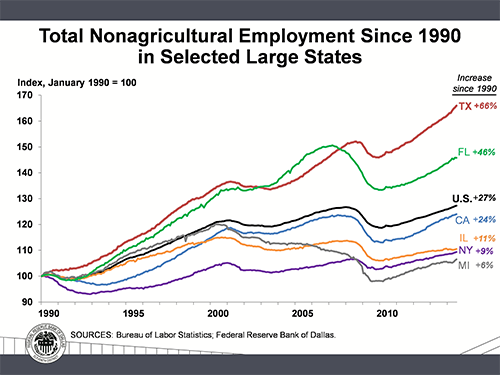

Here is a graph depicting job growth in Texas versus the other large states that typically have drawn Indian and other investment and immigration:

For over two decades, we have outperformed the rest of the United States in job creation by a factor of more than 2 to 1. Over 23 years, only nine net new jobs have been created for every 100 that existed in New York in 1990, whereas in Texas, 66 jobs have been created.

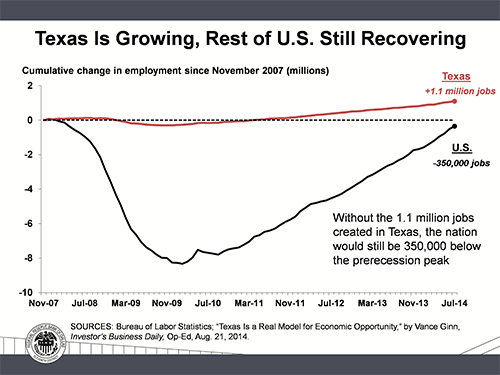

We have been especially prolific in creating jobs since the Great Recession waylaid the world at the end of 2007. Today, employment in Texas is 8.6 percent above its prerecession peak. The nation as a whole is 0.5 percent—zero point five percent—above its previous peak. However, if you take Texas out of the U.S. economy, statistically speaking, you see that the U.S. ex-Texas still has not caught up to its prerecession employment levels. Here is a graph that shows the margin of difference in employment performance:

According to Bureau of Labor Statistics’ payroll employment data, Texas has created 1,100,600 jobs since November 2007; the rest of America is still 349,600 jobs shy of the prior employment peak.

Texas has been the crucible of job creation in America.

More than Oil and Gas; Jobs Well-Distributed

It is a common perception that the jobs that have been created here are primarily in the burgeoning energy sector. It is true that Texas is an energy powerhouse: We produce more than 3 million barrels of oil and 21 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day. To put this in perspective, Texas produces more oil than Kuwait or Venezuela or, if you’d like, more oil than the amount the U.S. imports from the Middle East. With regard to natural gas, Texas produces more than all 28 countries of the European Union combined.

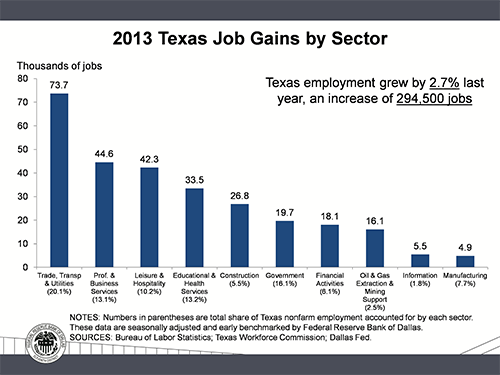

Of course, the energy sector is a significant driver for the Texas economy. Last year, the state saw an increase of 16,100 jobs related to oil and gas extraction and associated support services. We are grateful for every one of them. Yet there are seven other sectors of the Texas economy that produced more jobs than the energy sector last year. Here is a graphic summary of where jobs were created in the Lone Star State in 2013:

In terms of number of jobs created, the leading sectors in Texas last year were trade, transportation and utilities (accounting for 73,700), professional and business services (44,600), leisure and hospitality (42,300), educational and health services (33,500), construction (26,800), government (19,700) and financial activities (18,100).

This year through July, Texas employment has already increased by 238,200 jobs, a 3.6 percent annualized growth pace. Over the 12 months ending this July, Texas added just shy of 400,000 jobs—more jobs than any other state. Clearly, Texas employment is growing at an impressive clip.

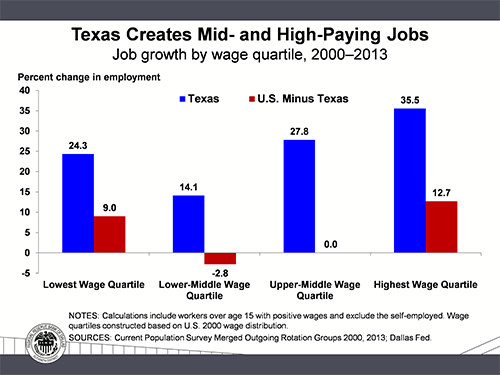

Another misperception is that all of these jobs created in Texas are low-paying jobs. Wrong. We have been creating jobs in every income quartile, unlike the rest of the country. This graph, recently updated, covers the 13-year period from 2000 to 2013. It charts job creation by wage quartile in Texas and in the nation ex-Texas.

As you can see, Texas has had healthy growth in every income quartile, while, without Texas, the United States has actually seen job destruction, on net, in the two middle-income quartiles. (This fact deeply concerns me because middle-income groups are the backbone of America.)

U.S. Economy Is on the Mend

The reality, Mr. Ambassador, is that Texas is part of the United States and, all told, our economy is on the mend from the frightful shock of the financial and economic implosion of 2007–09.

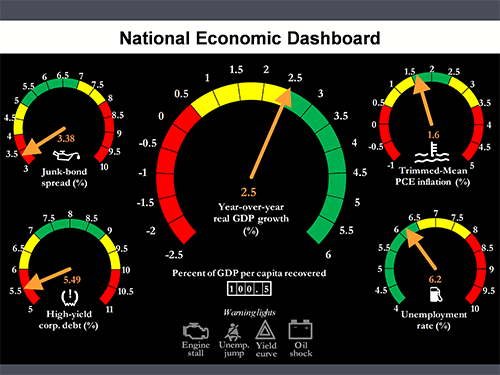

This is the dashboard that we at the Dallas Fed use to track our national economy:

The Federal Reserve is mandated by the laws of the United States to manage monetary policy to achieve full employment while maintaining price stability and “moderate interest rates” over time.[1]

A ‘Hindu Goddess’

As you can see from this graphic, unemployment has declined to 6.2 percent, and the dynamics of the labor market are improving. At the Federal Open Market Committee, where we set monetary policy for the nation, we have been working to better understand these employment dynamics. This is no easy task. Bill Gross, one of our country’s preeminent bond managers, made a rather pungent comment about our efforts. He noted that President Harry Truman “wanted a one-armed economist, not the usual sort that analyzes every problem with ‘on the one hand, this, and on the other, that.’” Gross claimed that Fed Chair (Janet) Yellen, in her speech given recently at the Fed’s Jackson Hole, Wyo., conference, introduced so many qualifications about the status of the labor market that “instead of the proverbial two-handed economist, she more resembled a Hindu goddess with a half-dozen or more appendages.”[2]

Whether you analyze the labor markets with one arm or two, or six or 19, the issue is how quickly we are approaching capacity utilization, so as to gauge price pressures. After all, a central bank is first and foremost charged with maintaining the purchasing power of its country’s currency. Like most central banks around the world, we view a 2 percent inflation rate as a decent intermediate-term target. Of late, the various inflation indexes have been beating around this mark. Just this last Friday, the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) index for July was released, and it clocked in at a 1 percent annualized rate, a pace less than the run rate of April through June.

Does this mean we are experiencing an inflation rate that is less than acceptable? I wonder. At the Dallas Fed, we calculate a trimmed mean inflation rate for personal consumption expenditures to get what we think is the best sense of the underlying inflation rate for the normal consumer. This means we trim out the most volatile price movements in the consumer basket to achieve the best sense we can of underlying price stability. In the July statistics, we saw some of the fastest rates of increases in a while for the largest, least-volatile components of core services, such as rent and purchased meals.[3] So the jury is out as to whether we have seen a reversal in the recent upward ascent of prices toward our 2 percent target.

As to achieving “moderate interest rates,” the dashboard shows that we have overshot the mark. Interest rates on the lowest-quality credits—on “junk”—are historically low, as are the spreads they are priced at above the current historically low nominal rates for investment-grade credits. I have been involved with the credit markets since 1975. I have never seen such ebullient credit markets. The 30-year Treasury yield is trading at a hair over 3 percent. If Ambassador Jaishankar and I were to abandon our service to our respective nations and form a company, we would use our good names to borrow as much money as we could at current rates.

And this, indeed, is happening. U.S. companies have used this bond market and borrowing rate hiatus from normalcy to pile up cheap, nearly cost-free balances. This cheap and abundant monetary fuel, with the proper incentives from the fiscal and regulatory authorities, can be deployed to the benefit of company stakeholders (shareholders and employees) to enrich and grow the economy. In this sense, we are unique in the world.

Mr. Ambassador, American businesses are rich and muscular. And those muscles are being flexed. For example, just two days ago, the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) released its Purchasing Managers Index. The data surprised most all forecasters to the upside. Activity was broad based: 17 of 18 industries surveyed reported growth in August, and new orders reached a 10-year high. Today, the ISM released its nonmanufacturing index, which registered the highest level in nine years. These reports echo a string of others—including the Beige Book survey of regional economic conditions released yesterday by the Federal Reserve—that underscore the healing that is taking place in the U.S. economy despite our having what is, in truth, a dysfunctional and counterproductive fiscal and regulatory environment. All we need now is for the fiscal and regulatory authorities—Congress and the executive branch—to unleash the animal spirit of business that is well nourished with the feed of cash and ready to roll.

Wodehouse’s Perspective

I happen to share a common bond with Indians: I have long been a reader of P.G. Wodehouse.[4] In his book, Big Money, published in 1931, he has a wonderful passage in which a young lad nicknamed Biscuit describes the woman he has fallen in love with: “… when I think that a girl can be such a ripper and at the same time so dashed rich, it restores my faith in the Providence which looks after good men.” Be it Providence or the Fed, the American business community is at present a “ripper”—it looks darned good—and is “dashed rich.” We are poised for a healthy, sustainable expansion. The men and women in this room see it in Texas. I trust they will see it in the whole of the United States. And I trust they and others like them will use it to lead the world, including India, to expanded economic prosperity.

Thank you for having me here this evening.

Notes

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve System.

- The Fed’s policy objectives, as stated in Section 2A of the Federal Reserve Act, are that “the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Open Market Committee shall maintain long run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy’s long run potential to increase production, so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” See www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/section2a.htm.

- See “The Fed’s Evenhanded Policy,” by Randall W. Forsyth, Barron’s, Aug. 23, 2014.

- For the latest reading of the Dallas Fed’s alternative measure of trimmed mean PCE inflation, see www.dallasfed.org/research/pce/index.cfm.

- P.G. Wodehouse is widely read and wildly popular in India.

About the Author

Richard W. Fisher served as president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas from April 2005 until his retirement in March 2015.