Economic Conditions and the Key Structural Drivers Impacting the Economic Outlook

October 10, 2019

In the September Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, the Federal Reserve cut the federal funds rate by 25 basis points to a range of 1.75 to 2 percent. I supported this rate cut as well as the previous rate cut in July.

In addition, since mid-September, the New York Fed has announced a series of overnight and term repurchase agreement (repo) operations intended to provide additional liquidity to the overnight and term lending markets in order to maintain the federal funds rate within the target range. In the post-FOMC meeting press conference, Chairman Powell suggested that the Fed will consider additional actions in order to provide sufficient reserves consistent with our decision to implement policy in an ample-reserves regime. I do not plan to comment extensively on additional options, as we continue to debate and discuss them, other than to emphasize that I support more-permanent steps to ensure the proper functioning of repo and other short-term funding markets. I am also supportive of taking steps to adjust the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet in order to help achieve our objective of implementing policy in an ample-reserves regime.

In this essay, I will briefly review economic conditions in the U.S. I will then step back and discuss several key structural drivers that I believe are critical to the prospects for economic growth in the U.S. Finally, I will outline my current thinking regarding the stance of U.S. monetary policy.

Economic Outlook for the U.S.

Dallas Fed economists forecast growth for 2019 of approximately 2.1 percent. This forecast is based on estimated first-half growth of approximately 2.5 percent and an expectation for second-half growth of approximately 1.7 percent. This compares with a 2.5 percent rate of growth achieved in 2018.[1]

Dallas Fed economists had predicted some of the recent slowing due to the expected waning of the impact of fiscal stimulus. However, some of the slowing is also due to heightened trade tensions, which have contributed, at least in part, to decelerating rates of global growth as well as weakness in manufacturing and business direct investment in the U.S. Despite these headwinds, U.S. growth has been resilient primarily due to the strength of consumer spending, which accounts for approximately 70 percent of the U.S. economy. The consumer is bolstered, in particular, by a strong jobs market as well as improvements in the level of household debt to gross domestic product (GDP) which have occurred since 2008.[2]

On October 4, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported September jobs growth of 136,000. The current rate of unemployment is now approximately 3.5 percent.[3] This is the lowest level of U.S. unemployment in the past 50 years. To further gauge labor market slack, Dallas Fed economists also look at the U-6 measure of unemployment, which includes people who are unemployed, plus discouraged workers, plus workers who are working part time but would prefer to work full time. This measure now stands at approximately 6.9 percent,[4] below its prerecession low of 7.9 percent (reached in December 2006) and only slightly above its historical low of 6.8 percent (reached in October 2000).[5] These measures, as well as our Eleventh District surveys of employers and discussions with contacts, indicate that the U.S. economy is at or past the level of full employment. Many of our contacts report particular difficulty in hiring and retaining lower-skilled workers (who earn wages in a range of 12 to 15 dollars per hour), as well as finding and retaining more skilled workers, who typically require some level of advanced specialized training.

Regarding inflation, the headline measure of personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation is currently running at 1.4 percent on a 12-month basis.[6] At the Dallas Fed, we prefer to focus on the Dallas Fed Trimmed Mean PCE measure of inflation, which removes the most extreme moves up and down in PCE components. This measure is currently running at approximately 2 percent on a 12-month basis.[7] Dallas Fed research suggests that the trimmed mean measure of inflation is a good indicator of future inflation trends. On that basis, it is our expectation that the headline PCE inflation rate will reach the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target over the medium term.

Key Structural Drivers Impacting the Economic Outlook

I am often asked: Why is growth today so much slower than it was in the 1980s and the 1990s? Why are market-determined interest rates so much lower? Why is the federal funds rate today so much lower than in these previous periods?

A big part of the answer to these questions lies in the fact that there have been substantial secular changes in the U.S. economy. At the Dallas Fed, we refer to these as “structural drivers.” These structural drivers include:

- Demographic Trends

- Technology, Technology-Enabled Disruption, and Education/Skills Training

- Globalization and Trade

- The Path of U.S. Government Debt to GDP

Of course, there are other major trends. One of the most significant is climate change and its implications for the increased frequency and intensity of severe weather events, such as hurricanes, droughts, floods, and other disruptive impacts (see the essay “A Brief Discussion Regarding the Impact of Climate Change on Economic Conditions in the Eleventh District,” June 27, 2019). At the Dallas Fed, we will continue to do research and analyze the various impacts of climate change on the Eleventh District, as well as the U.S. and the world.

The following is a discussion of four primary structural drivers. Over the past several years, our Dallas Fed economists have spent a substantial amount of time discussing these key structural drivers and trying to understand their implications for economic outcomes and economic policy decisions in the U.S.

1. Demographic Trends

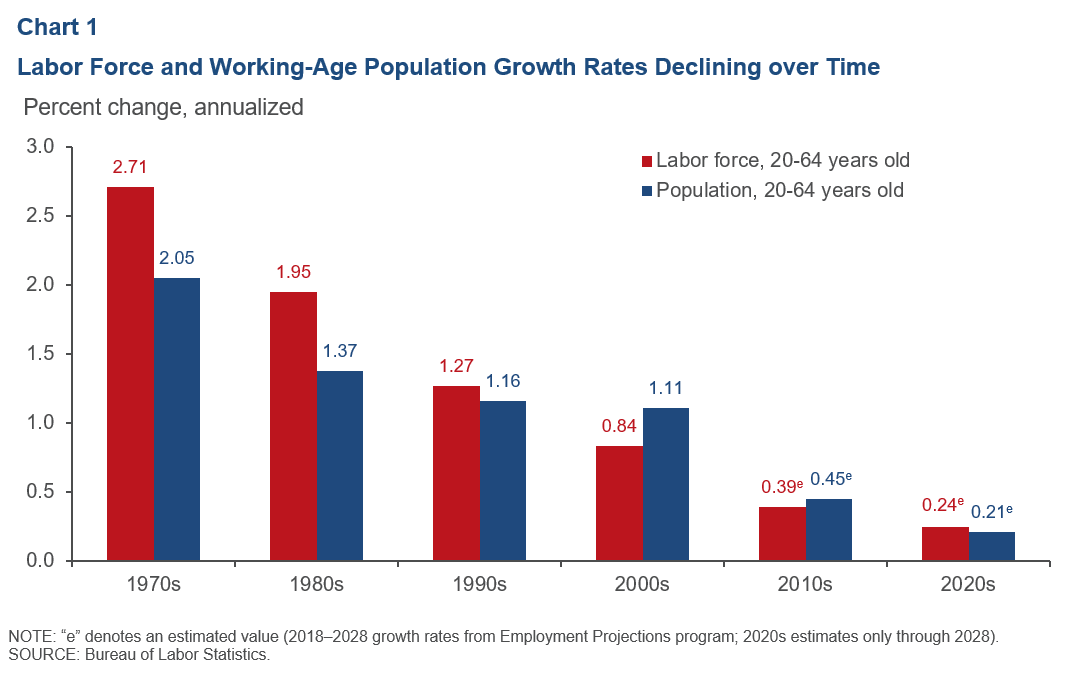

The U.S. population is aging. The median age of the population has risen from approximately 35.3 years in 2000 to 38.2 in 2018.[8] The share of population 65 years or older has risen from 12.4 percent in 2000 to 16.0 in 2018.[9] As baby boomers increasingly leave the workforce, U.S. labor force growth is slowing. Slower labor force growth is critically important because GDP growth is made up of growth in the workforce plus growth in labor productivity. Unless slower workforce growth is offset by improved productivity growth, U.S. GDP growth will slow. Chart 1 shows the ongoing trends of population aging and declines in population and labor force growth rates in the U.S.

Another way to look at labor force growth is to look at the labor force participation rate. This rate is the percentage of the population age 16 and older that either has a job or is actively looking for work. This rate has decreased from approximately 66 percent in 2007 to 63.2 percent today.[10] Dallas Fed economists believe that the bulk of this decline is due to the aging of the population. We expect this measure to decline further to 61 percent over the next 10 years as the population continues to age and the rate of workforce growth continues to decelerate.[11] As discussed earlier, these trends create a significant headwind for GDP growth.

Labor force growth has been a key aspect of sustained U.S. growth over the past several decades. Increasing female labor force participation boosted growth from the 1950s to the 1990s. Since the 1990s, U.S. labor force growth has been helped by older workers staying in the workforce longer. Throughout our history, immigration of workers has also been a key aspect of U.S. labor force growth.

The Dallas Fed does a substantial amount of research on immigration trends. Pia Orrenius, senior economist at the Dallas Fed, has pointed out that more than 50 percent of workforce growth over the past 20 years has come from immigrants and their children.[12] Her research indicates that immigrants tend to take jobs at both the low end and the high end of the workforce and do not appear to have negatively impacted wages of indigenous workers overall. Her research also indicates that, from a policy point of view, the U.S. might be well-served to restructure its immigration policies to be more employer- and skills-based. Her work suggests that if the U.S. is to improve workforce growth in the years ahead, immigration is likely to be a key element of this effort.

In summary, slowing workforce growth is likely to be a continuing headwind for U.S. economic growth. Finding ways to grow the workforce will be critical to improving GDP growth prospects for the U.S.

2. Technology, Technology-Enabled Disruption, and Education/Skills Training (See Appendix)

While the U.S. has experienced rapid improvements in technology and substantial development of technology-enabled disruption in a variety of industries, measures of labor force productivity growth have been surprisingly sluggish. As explained earlier, GDP growth is made up of growth in the workforce and growth in productivity. If workforce growth is slowing due to aging of the population, it is critical that we find ways to improve productivity growth.

Output per worker grew on average approximately 1.9 percent per year in the 1990s, slowed to 1.4 percent in the 2000s and has slowed further to 1.1 percent since 2010.[13] Our hypothesis at the Dallas Fed is that intensifying technology and technology-enabled disruption is improving the productivity of a substantial number of U.S. companies and industries. Productivity improvement is measured not by industry, but by improvement in average output per worker in the overall economy. Part of the issue is that technological innovation may impact output per worker with a lag, and some believe that we may see improvements in these output statistics in the future, after a period of adoption and adaptation. However, Dallas Fed economists also believe that a key reason that we don’t see better workforce productivity data is that technological innovations are likely being experienced differently by workers based on their educational attainment and/or skill levels.

In particular, if you are one of the 46 million workers in this country with a high school education or less, and/or have a routine type of middle-skills job, you are likely finding your job is being either restructured or eliminated as a result of technology. Many of those workers with less education may be finding that their real wages and productivity are declining in a new age in which skills training and educational achievement levels are increasingly critical to adapting to the jobs market.

The increase in technology and technology-enabled disruption is also putting a spotlight on the adaptive capabilities of the workforce. In particular, better educational achievement and improved skill levels are critical to improving workforce adaptability. Various research studies have highlighted that the educational achievement and skill levels of the U.S. workforce have lagged those of other developed countries. In surveys of 29 participating Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries, the U.S. ranked 20th in assessments of adult literacy and math skills.[14] It also ranked 24th out of 35 developed countries in measures of math, science and reading skills among 15-year-olds.[15]

Research by Eric Hanushek of Stanford University with Ludger Woessmann of the University of Munich suggests that improvements in math and science skills could translate into meaningful improvements in potential U.S. GDP growth.[16]

Dallas Fed economists believe that in order to address the powerful structural driver of technology and technology-enabled disruption, the U.S. must do more to improve early-childhood literacy, college readiness, and skills training at our high schools and community colleges. These efforts should be a powerful investment in improving the quality and productivity of our human capital which, in a technological age, are essential to higher levels of GDP growth in the U.S.

3. Globalization and Trade

The U.S. has less than 5 percent of the world’s population.[17] It is estimated that the Standard and Poor’s 500 companies in the U.S. now generate in excess of 40 percent of their revenues from outside the U.S.[18] In addition, in order to be globally competitive, many of our companies have developed highly sophisticated cross-border supply-chain and logistics arrangements with Mexico and Canada. Dallas Fed economists believe these arrangements have helped these companies improve their global competitiveness.

Dallas Fed economists have suggested that U.S. trade analysis should segment our trading relationships into those which are primarily final goods versus those which are largely intermediate goods. For example, the trading relationship with Mexico is predominantly intermediate goods. This helps explain why approximately 40 percent of the value of U.S. imports[19] from Mexico consists of value added from the U.S., which is indicative of integrated supply-chain and logistics relationships that have allowed U.S. companies to add jobs and increase their global competitiveness.[20] On the other hand, the trading relationship with China is primarily a final-goods relationship (approximately 4 percent of the value of U.S. imports from China contains value added from the U.S.).[21] In addition, as has been much discussed, the trade relationship with China is fraught with issues related to technology transfer and intellectual property rights.

While trade is important to the U.S., it is vital to many countries outside the U.S. Exports currently account for approximately 12 percent of U.S. GDP.[22] However, exports account for approximately 47 percent of German GDP,[23] 20 percent of euro-area GDP[24] and 27 percent of emerging-market GDP.[25] As a result, it is not surprising that escalating trade tensions disproportionately impact non-U.S. economic growth. It is also not surprising that as trade uncertainty has risen, particularly with Mexico and Canada, it has had some dampening impact on U.S. manufacturing and investments relating to global supply-chain arrangements.

If your job is being disrupted or eliminated in the U.S., the recent public narrative has suggested that it is probably due to globalization—either trade or immigration. Dallas Fed economists believe that this disruption is more likely due to technology and/or technology-enabled disruption. Our economists point out that if policymakers get this diagnosis wrong, we are likely to make policy decisions which impede globalization—and the net effect is likely to be slower growth in the U.S. This misdiagnosis would not be so consequential if we weren’t so highly leveraged at the federal government level.

4. The Path of U.S. Government Debt to GDP

U.S. government debt held by the public now stands at approximately 76 percent of GDP,[26] and the present value of unfunded entitlements is estimated at approximately $59 trillion.[27] The recent tax legislation and bipartisan budget compromise legislation are likely to exacerbate these issues, and the U.S. deficit is poised to exceed $1 trillion in 2020.[28] As a consequence of this rising level of debt, the U.S. will have less fiscal capacity to fight the next recession.

The U.S. relies heavily on the presumption that the dollar is likely to be the world’s reserve currency for the foreseeable future. That is, global investors tend to overweight their asset allocations to dollars. This, of course, is highly beneficial when the projected issuance of U.S. Treasury securities is likely to rise substantially. However, it is worth considering the implications if the dollar ceases to be the world’s reserve currency sometime in the future. Is it wise for the U.S. to rely so heavily on this presumption in managing its financial affairs?

Previously, I have written about the historically elevated level of corporate debt in the U.S. I have noted that this is probably not, at this point, a systemic risk but more likely an amplifier in the event of an economic slowdown (see “Corporate Debt as a Potential Amplifier in a Slowdown,” March 5, 2019). It is worth noting that high levels of government debt, along with elevated levels of corporate debt, mean that the U.S. economy is becoming much more interest rate sensitive. That is, increases in interest rates would likely require a higher proportion of cash flow in order to service corporate and government debt obligations.

Structural reforms and other actions that moderate the path of future government debt growth may be advisable to keep this short-term-growth tailwind from becoming a medium- and longer-term headwind to economic growth in the U.S. In the meantime, this historically high level of U.S. government debt means that there will likely be less capacity to use fiscal policy in the event of an economic downturn.

Implications of Key Structural Drivers

Many of the issues raised by these structural drivers are primarily outside the purview of monetary policy. That is, while monetary policy has a key role to play, I believe it is likely that we will need broader economic policy actions if we are to improve the growth potential of the U.S. economy and the future prosperity of our citizens.

Immigration and trade policies, education reform and skills training, and managing the future path of U.S. government debt are all policy judgments that are made outside the purview of monetary policy and the remit of the Federal Reserve. However, part of my job as a central banker at the Dallas Fed is to share our economic research and call out these issues to elected and appointed officials in hopes that our research will help inform their judgments and highlight the need for broader economic policy at the city, state and federal levels. I am hopeful that this effort will help improve economic performance in the Eleventh District and the nation.

Discussion of the Current Stance of U.S. Monetary Policy

As discussed earlier, I supported the FOMC’s 25-basis-point reductions in the federal funds rate at the July and September meetings. I am concerned that if non-U.S. growth continues to decelerate, and weakness in U.S. manufacturing and business investment intensifies, this weakness could spread to the broader U.S. economy, ultimately impacting consumer confidence and spending.

While strong consumer spending is a welcome underpinning to growth, I recognize that it is more of a “coincident” indicator; that is, it doesn’t provide great insight regarding future prospects for the economy. Consumer confidence can be fragile—one or two months of weak jobs reports could put a dent in consumer confidence and spending habits, which could further slow GDP growth. This is why I’ve repeatedly said that if we wait to see weakness in the consumer before taking action, we will have likely waited too long. From a risk-management point of view, that is a mistake I prefer not to make.

A reality check for my thinking has been the level and shape of the U.S. Treasury curve. The 10-year Treasury rate has declined from 3.24 percent on November 8, 2018, to 1.59 percent at the time of this essay.[29] During that same time period, the federal funds rate has declined from a range of 2 to 2.25 percent to 1.75 to 2 percent. It is worth noting that the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) median estimate of the federal funds rate at the end of 2021 has gone from 3.25 to 3.50 percent in the September 2018 summary[30] to 2 to 2.25 percent in the recent September 2019 submission.[31]

It is my view that the level and shape of the Treasury curve are reflective of slowing global growth, heightened trade tensions and a more pessimistic view regarding the prospects for U.S. economic growth. Pessimism regarding prospects for global growth is also one key reason why approximately 22 percent of global government debt is now trading at negative yields.[32]

I believe that moves in U.S. market-determined rates are consistent with concerns about economic weakness spreading more broadly to other parts of the U.S. economy. For me, these moves in market-determined rates are a reality check that suggests the setting of the federal funds rate was tighter than appropriate prior to the July and September FOMC meetings. In this regard, I intend to continue to carefully monitor the yield curve and gauge the ongoing implications of negative gaps between the federal funds rate and yields on longer-dated Treasury securities.

At this juncture, having adjusted the policy rate twice this year, it is my intention to take some time to carefully monitor economic developments. I am mindful of the potential excesses and imbalances that can be created as a result of excessive accommodation. I am also alert to the possibility that recent escalations in trade tensions could moderate somewhat and this, in turn, might alleviate some of the downside risks to the U.S. and global economies. In any event, I intend to avoid being rigid or predetermined from here, and plan to remain highly vigilant and keep an open mind as to whether further action on the federal funds rate is appropriate.

APPENDIX

A Note on Technology-Enabled Disruption

As Dallas Fed economists have been discussing for the past several years, technology-enabled disruption means workers are increasingly being replaced by technology. It also means that existing business models are being supplanted by new models, often technology-enabled, for more efficiently selling or distributing goods and services. In addition, consumers are increasingly using technology to shop for goods and services at lower prices with greater convenience—having the impact of reducing the pricing power of businesses which has, in turn, caused them to further intensify their focus on creating greater operational efficiencies. These trends appear to be accelerating.

It is likely that disruption is a factor in economic outcomes being increasingly skewed by the educational attainment levels of workers. For example, for those who have a college degree, the unemployment rate stands at 2.0 percent, and the labor force participation rate is 73.9 percent. If you have some college education, the unemployment rate is 2.9 percent and the participation rate is 65.1 percent; a high school diploma, the unemployment rate is 3.6 percent and the participation rate is 57.8 percent; and some high school education, the unemployment rate is 4.8 percent and the participation rate is 46.0 percent.[33]

Increasingly, workers with lower levels of educational attainment are seeing their jobs restructured or eliminated. Unless they have sufficient math and literacy skills or are retrained, these workers may likely see their productivity and incomes decline as a result of disruption. This may help explain the muted levels of wage gains and overall labor productivity growth we see in the U.S. as well as other advanced economies.

The impact of technology-enabled disruption on the workforce is likely less susceptible to monetary policy—addressing this challenge requires structural reforms. The reforms could include actions which would be aimed at improving early childhood literacy, as well as improving math, reading and science achievement levels among high school students. These efforts could help boost overall college readiness in order to increase the percentage of students who graduate college in six years or less—now estimated at 60 percent in the U.S.[34] Addressing the impacts of technology-enabled disruption will also require stepped-up efforts to increase middle-skills training in cities across the U.S. in order to improve employment, close the skills gap (not enough workers to fill skilled jobs) and raise worker productivity. These initiatives could improve educational achievement levels in order to better equip our citizens to thrive in a world that increasingly demands greater education, training and adaptability.

Disruption may also help explain why companies, facing one or more disruptive competitors, have been more cautious about making capacity-expansion decisions and investing in major capital projects. The recent tax legislation may help create incentives to improve the level of capital investment.

To deal with disruptive changes and lack of pricing power, many companies are seeking to achieve greater scale economies in order to maintain or improve profit margins. This may help explain the record level of merger-and-acquisition activity globally over the past few years.

Notes

- Data are from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) Annual Update, published July 26, 2019.

- Data are from the BEA, Federal Reserve Board and Haver Analytics. Household debt is from the Federal Reserve Board’s flow of funds series and is defined as households and nonprofit organizations; debt securities and loans; liability.

- As of September 2019. Data are from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

- As of September 2019. Data are from the BLS.

- Data are from the BLS. Note that unlike the unemployment rate, which goes back to 1948, this series only goes back to 1994.

- As of August 31, 2019. Data are from the BEA.

- As of August 31, 2019. Data are from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

- Data are from the Census Bureau.

- Data are from the Census Bureau.

- As of September 2019. Data are from the BLS.

- Data are from BLS employment projections and Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas analysis.

- See “How Does Immigration Fit into the Future of the U.S. Labor Market?” by Pia Orrenius, Madeline Zavodny and Stephanie Gullo, Migration Policy Institute, August 2019.

- Data are from the BEA and BLS.

- According to the Survey of Adult Skills (Program for International Assessment of Adult Competencies) for 2012 and 2015 by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the U.S. ranks 17th in literacy and 23rd in math out of 29 countries and 15th in problem solving in technology-rich environments out of 26 countries. An average of scores across the literacy and math categories places the U.S. 20th.

- According to the 2015 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) by the OECD, the U.S. ranks 19th in science, 20th in reading and 31st in mathematics out of 35 OECD countries. An average of the scores across the three categories places the U.S. 24th.

- Eric Hanushek and Ludger Woessmann (2016) estimate that a sustained 25-point increase in U.S. students’ average PISA scores could lead to an increase of 0.5 percentage points in potential GDP growth in the longer run. See “Skills, Mobility, and Growth,” by Hanushek and Woessmann in Economic Mobility: Research & Ideas on Strengthening Families, Communities & the Economy, Alexandra Brown, David Buchholz, Daniel Davis and Arturo Gonzalez, ed., St. Louis: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2016, pp. 423–49. Also see “Human Capital in Growth Regressions: How Much Difference Does Data Quality Make?” by Angel de la Fuente and Rafael Doménech, Journal of the European Economic Association, vol. 4, no. 1, 2006, pp. 1–36; and “Growth and Human Capital: Good Data, Good Results,” by Daniel Cohen and Marcelo Soto, Journal of Economic Growth, vol. 12, no. 1, 2007, pp. 51–76.

- Data are from the 2018 United Nations population estimates.

- See “S&P 500 Global Sales,” by Howard Silverblatt, S&P Dow Jones Indexes, 2019.

- See “Give Credit Where Credit Is Due: Tracing Value Added in Global Production Chains,” by Robert Koopman, William Power, Zhi Wang and Shang-Jin Wei, National Bureau of Economic Research, NBER Working Paper no. 16426, 2011.

- See “Intra-Industry Trade with Mexico May Aid U.S. Global Competitiveness” by Jesus Cañas, Aldo Heffner and Jorge Herrera Hernández, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Second Quarter, 2017.

- See note 20.

- Data are from the BEA.

- Data are from Bundesbank.

- Data are from the Statistical Office of the European Communities/Haver Analytics.

- Data are from the International Monetary Fund/Haver Analytics.

- As of second quarter 2019. Data are from the U.S. Department of the Treasury and Bureau of Economic Analysis.

- “The 2019 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds,” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, April 22, 2019.

- August 2019 Forecast Update, Congressional Budget Office.

- As of market close October 9, 2019. Data are from Bloomberg.

- Federal Open Market Committee Summary of Economic Projections, September 26, 2018.

- Federal Open Market Committee Summary of Economic Projections, September 18, 2019.

- As of market close October 9, 2019. Data are from Bloomberg.

- As of September 2019. Data are from the BLS.

- See undergraduate retention and graduation rates in “The Condition of Education 2019,” U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, May 2019.

About the Author

Robert S. Kaplan was president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2015–21.

The views expressed are my own and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve System.

I would like to acknowledge the contributions of Tyler Atkinson, Jennifer Chamberlain, Jackson Crawford, Jim Dolmas, Marc Giannoni, James Hoard, Drew Johnson, Evan Koenig, Karel Mertens, Demere O’Dell, Pia Orrenius, Kathy Thacker and Mark Wynne in preparing these remarks.