Ample reserves and the Friedman rule

Thank you for the kind introduction, Imène [Rahmouni-Rousseau]. It’s great to see so many old friends, and it’s a real honor to give a keynote address at this important conference.

As a policymaker, I have the opportunity to speak on a wide range of topics, but money markets are where I grew up as a central banker. So it’s a particular pleasure to take a deep dive into the more technical aspects of monetary policy implementation and to do so from the perspective of a policymaker rather than a practitioner.

Let me note that the views I express are mine and not necessarily those of my colleagues on the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC).

The Friedman rule and monetary policy implementation

In recent decades, central banks around the world have been shifting toward floor systems for monetary policy implementation. That shift has been motivated by the actions central banks had to take in response to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and subsequent stress episodes; by a growing appreciation of the benefits of floor systems across a wide range of economic and financial environments; and by post-GFC changes in bank regulations and banks’ own risk management, which increased the demand for liquidity and the costs of interbank transactions.

Among the key benefits typically cited for floor systems is that they do not put a price on liquidity. That is, in a floor system, banks’ demand for central bank reserves is satisfied at something close to market interest rates. Market rates are not materially higher than the remuneration on the marginal dollar of reserves, and correspondingly there is no incentive for banks to economize on reserves, the most liquid asset in the financial system.

As a result, floor systems satisfy a version of the Friedman rule.[1] The opportunity cost to banks of holding reserves is approximately equal to the central bank’s cost of supplying reserves, which most analysts view as small.[2]

In theory, because floor systems remove incentives to economize on liquidity, they should reduce liquidity risk in the financial system. Yet, in economies around the world that use floor systems, we have seen serious liquidity strains in recent years.

These episodes include the pressures on liability-driven investment funds in the U.K.; the banking challenges in the U.S. earlier this year; the repo market pressures in 2019; and, of course, the global dash for cash at the onset of the pandemic.

In light of these events, some observers have questioned whether floor systems deliver the promised liquidity benefits. Some have even argued that floor systems make liquidity risk worse—an idea I strongly disagree with. And some have questioned the other side of the Friedman rule equation, asking whether central banks can in fact supply large quantities of reserves at minimal cost to the financial system and society.[3]

Today, I will take on both sides of those critiques. I will argue that floor systems do reduce liquidity risk. But they don’t eliminate it. It remains incumbent on all players in the financial system—banks, other market participants, as well as central banks in our roles as both regulators and financial institutions—to appropriately manage liquidity risk. The appropriate strategies to manage liquidity risk look somewhat different in a floor system, and I think all players have work left to do to fully gain the benefits of these systems.

On the other side of the equation, the costs of supplying reserves, it’s important to distinguish between two types of floor systems. When the central bank’s balance sheet is only as large as needed to meet the demand for liabilities such as reserves and currency, we call the system a liability-driven floor. That’s the approach we’ve selected for the long run in the United States, where our long-run operating regime will supply “ample” reserves. The FOMC deliberated long and hard over the word “ample,” and it contrasts with words like “abundant” and “super-abundant” that describe higher levels of reserves.[4] I don’t see large costs of supplying the quantity of reserves needed to establish a liability-driven floor.

There are also circumstances, such as the pandemic, in which it is appropriate for central banks to acquire additional assets to provide monetary accommodation or address severe strains in market functioning. Such balance sheet expansions create an asset-driven floor system. Asset-driven floors can pose some challenges. We can mitigate these challenges when circumstances make asset purchases appropriate, but it is better to minimize the challenges when we can. That is one reason I think it’s important to continue normalizing the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. (Another reason, of course, is that we need to remove monetary accommodation to restore price stability.)

In the rest of my remarks, I’ll address three topics. First, I’ll review the fundamentals of how floor systems work. Second, I’ll describe key policy lessons from the liquidity stress episodes of recent years. Finally, I will turn to the distinction between liability-driven and asset-driven floors and the challenges that very high levels of reserves can create. Throughout, I will draw on my experience both in my current role as a policymaker and in my previous role as manager of the System Open Market Account, leading the Open Market Trading Desk at the New York Fed that is responsible for implementing the Fed’s operating regime.The fundamentals of floor systems

Let’s begin by fixing ideas: What is a floor system? And how does it implement monetary policy?

To answer these questions, we need to consider reserves’ special role in the financial system. Reserves are funds that commercial banks, and sometimes other financial institutions, hold in accounts at the central bank. Payments between banks, or between customers of two different banks, are typically settled by transferring reserves from one bank’s reserve account to the other’s. Reserves’ use in settling payments makes them a unique asset. Reserves are always and immediately liquid. Other assets may be viewed as highly liquid if market participants can usually convert them into reserves quickly and at low cost. But no other asset is ever as safe and liquid as reserves.

Banks hold reserves for three main reasons. Banks use reserves throughout the day to settle payments. They may hold additional reserves, above typical daily needs, to manage liquidity risk by buffering against unexpected payment outflows. And banks may hold reserves to satisfy regulations and supervisory guidance, including formal reserve requirements, or as part of liquid assets to meet broader liquidity regulations. Banks’ liquidity management and the resulting demand for reserves have evolved significantly since the Global Financial Crisis, a point I’ll come back to later.

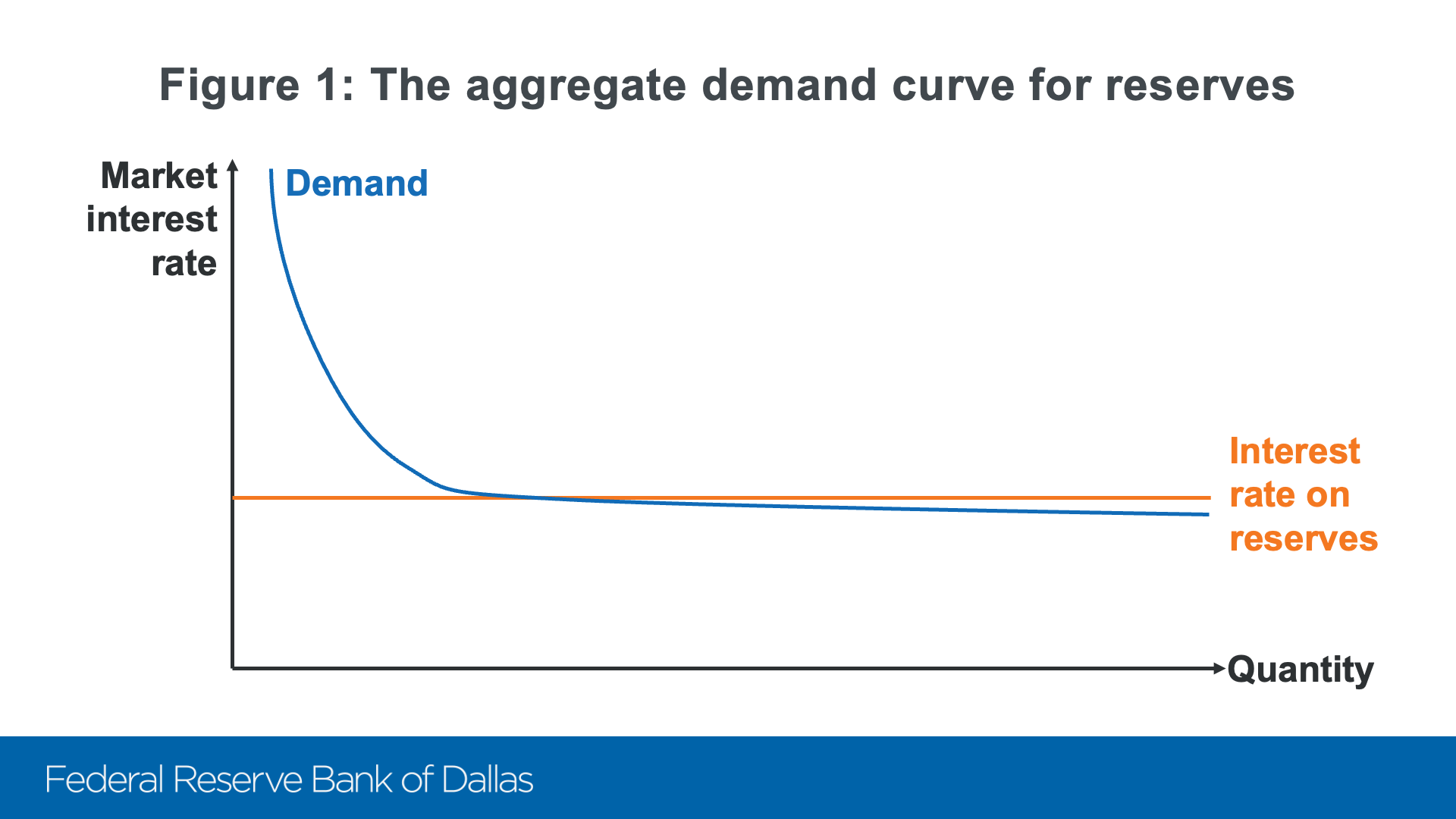

When a bank holds reserves, it forgoes putting that money into other assets such as loans or securities that may have higher risk-adjusted returns. Banks, individually and in the aggregate, therefore have a downward-sloping demand curve for reserves (Figure 1). At relatively low aggregate levels of reserves, banks are willing to tolerate a large spread between the returns on other assets and the return on reserves. As reserve levels increase, the spread between the returns on other assets and reserves must decrease. And when reserves reach levels that satisfy banks’ demand for liquid balances, the demand curve levels off with a market interest rate close to the interest rate the central bank pays on reserves.

There are two ways for the central bank to implement monetary policy in this environment.

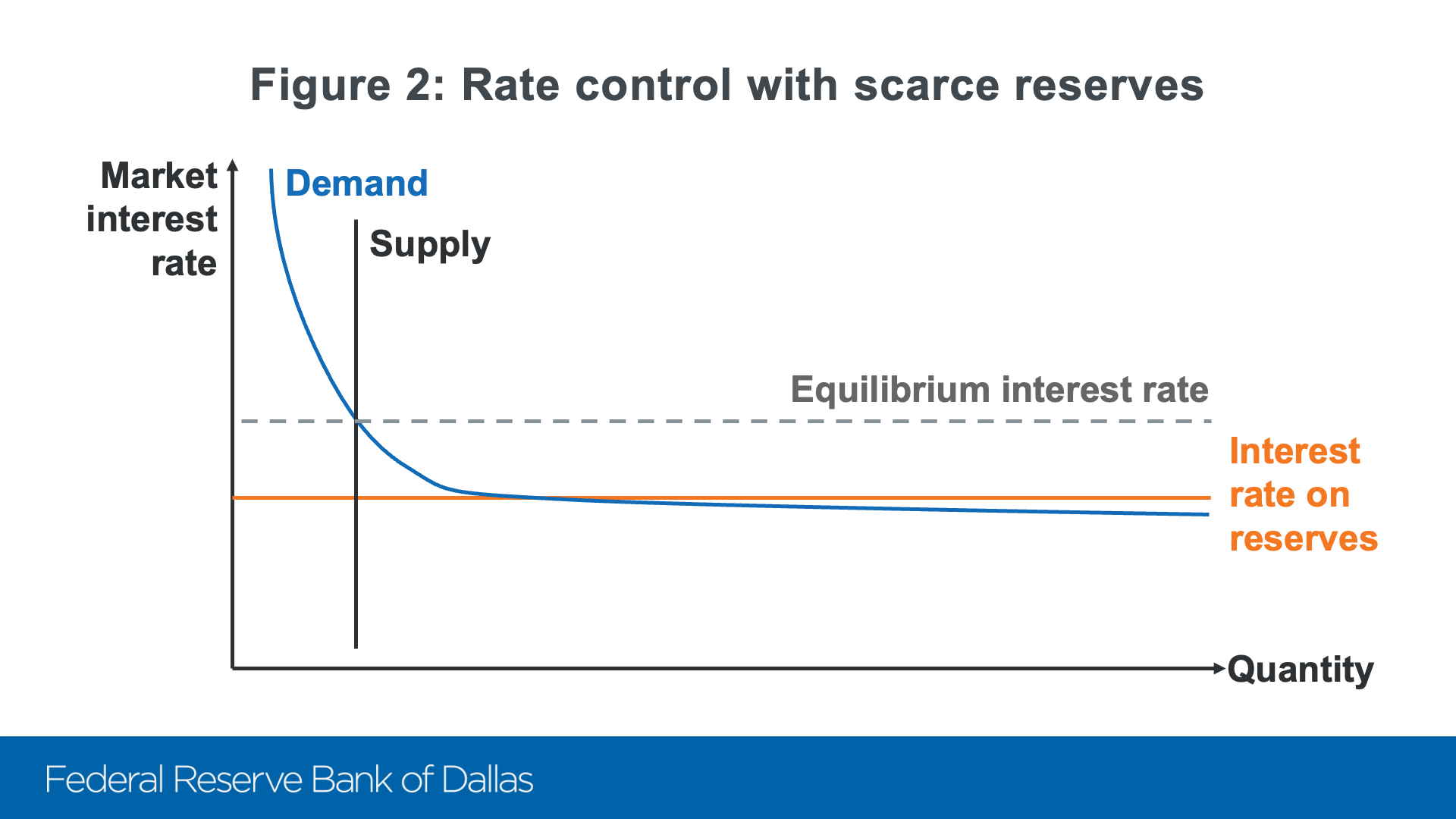

The central bank can provide a relatively limited—but potentially still quite large—supply of reserves, intersecting with the steep part of the demand curve (Figure 2). The central bank must then adjust reserve supply so the market clears at the desired interest rate. Small changes to the supply or demand for reserves can lead to significant changes in the policy rate in this regime.

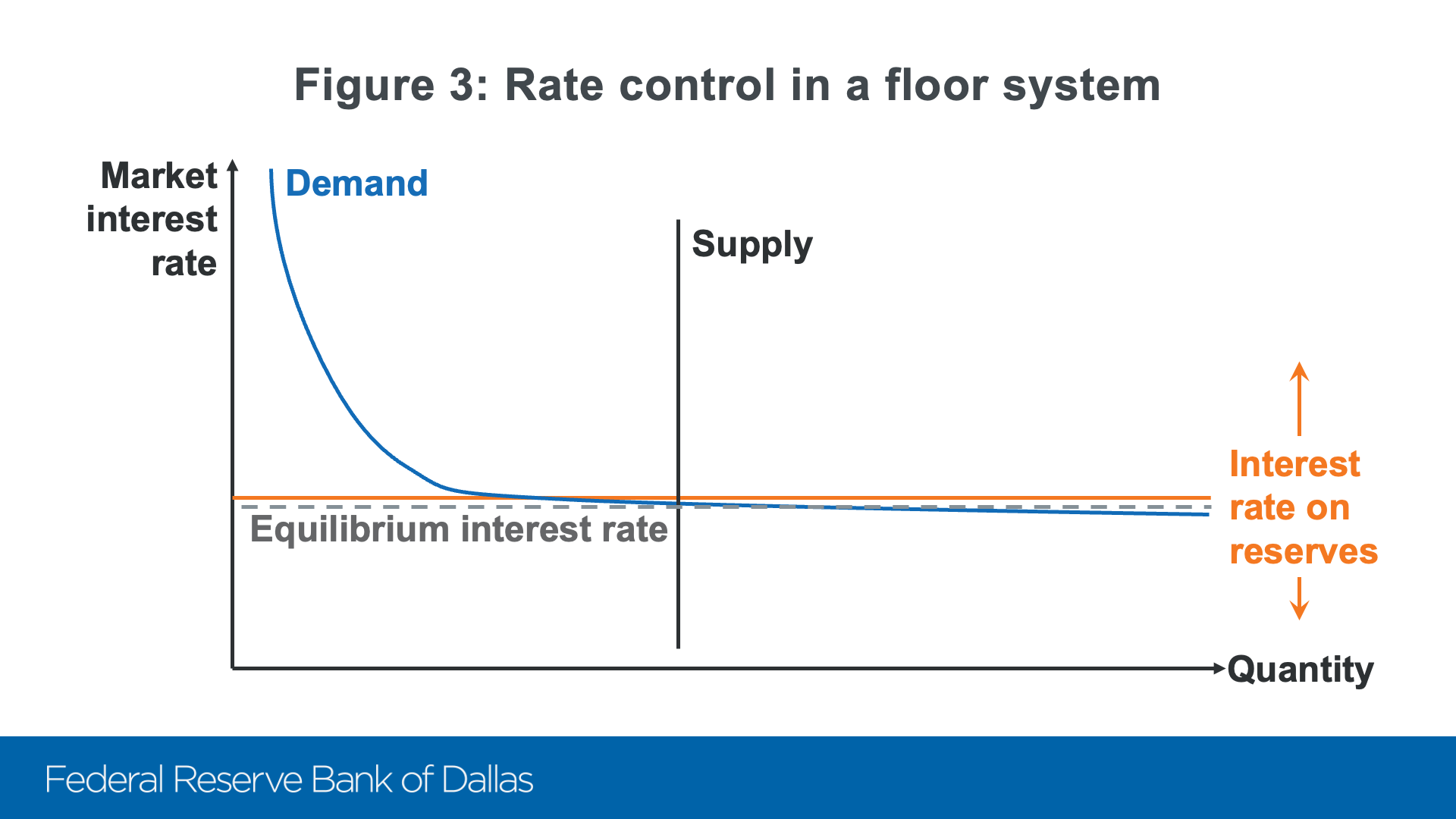

Alternatively, the central bank can provide more reserves and vary the interest rate on reserves to influence the market interest rate (Figure 3). Such an operating regime is called a floor system because the interest rate on reserves is intended to create a floor below money market rates. Commercial banks will not generally want to earn less in money markets than they can earn by keeping cash at the central bank.

However, the floor provided by interest on reserves can be soft if some money market participants are ineligible to hold interest-bearing reserve accounts or if commercial banks face costs of expanding their balance sheets. That’s why I’ve drawn the graph with the reserve demand curve dipping below the interest rate on reserves. To establish a firm floor, central banks may need additional tools. The overnight reverse repurchase agreement facility serves this purpose for the Fed.

The level of reserves in a floor system might not be much larger than the level of reserves needed to implement policy on the steep part of the demand curve. Post-GFC changes in regulations and banks’ liquidity risk management have substantially increased banks’ reserve demand.

As I see it, floor systems have three main benefits.

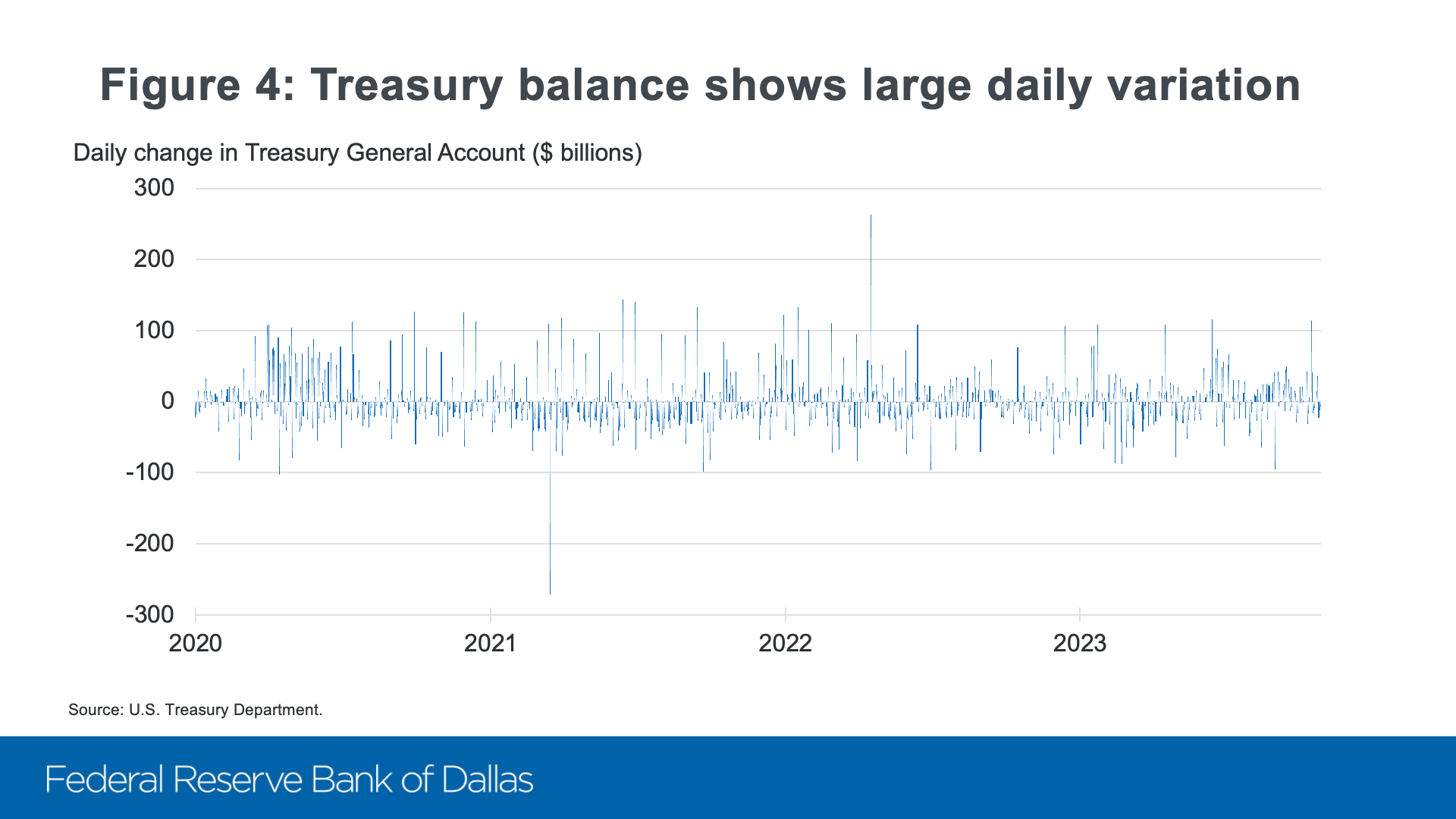

First, rate control in floor systems is more robust.[5] Since the Global Financial Crisis, both the supply of and the demand for reserves can be subject to much larger daily shocks. For example, in the U.S., the Treasury Department, other official entities and central counterparties hold accounts at the Fed that can drain reserves from the banking system.

As this chart in Figure 4 of daily changes in the Treasury General Account illustrates, the supply of reserves can regularly swing by tens of billions of dollars in a few days because of factors such as fiscal flows. And on the demand side, changes in liquidity regulations and risk management since the GFC have made banks’ demand for reserves less predictable.

Controlling money market rates requires absorbing these shocks to supply and demand. In a floor system, this is relatively straightforward. If the central bank operates on the flat part of the reserve demand curve, the system will remain on the flat part even after typical shifts of demand or supply, and money market rates won’t change much. By contrast, in a scarce reserves system, the central bank must actively manage the supply of reserves to offset the shocks—a challenging task when the shocks are difficult to predict.[6]

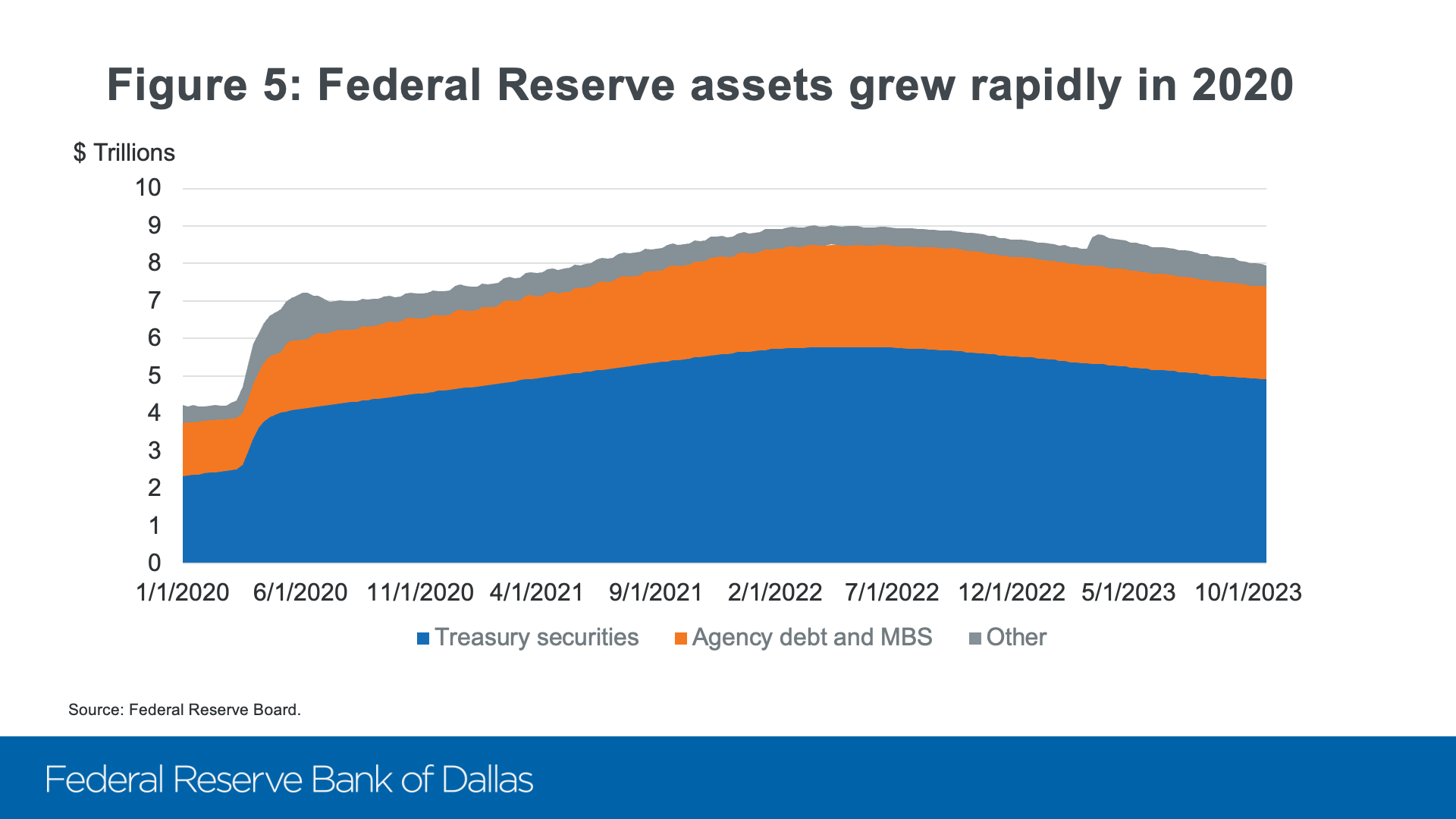

Second, floor systems continue to effectively control rates when the central bank expands its balance sheet to provide macroeconomic stimulus or support financial stability. In the United States, we saw this benefit most recently at the onset of the pandemic. The FOMC responded to disruptions in market functioning by purchasing Treasury and agency mortgage-backed securities at an unprecedented pace and scale.[7] Cumulatively, the Fed’s balance sheet expanded more than $2 trillion in a few months (Figure 5). At no point during this balance sheet expansion did we have any difficulty keeping the effective federal funds rate within the FOMC’s target range.[8]

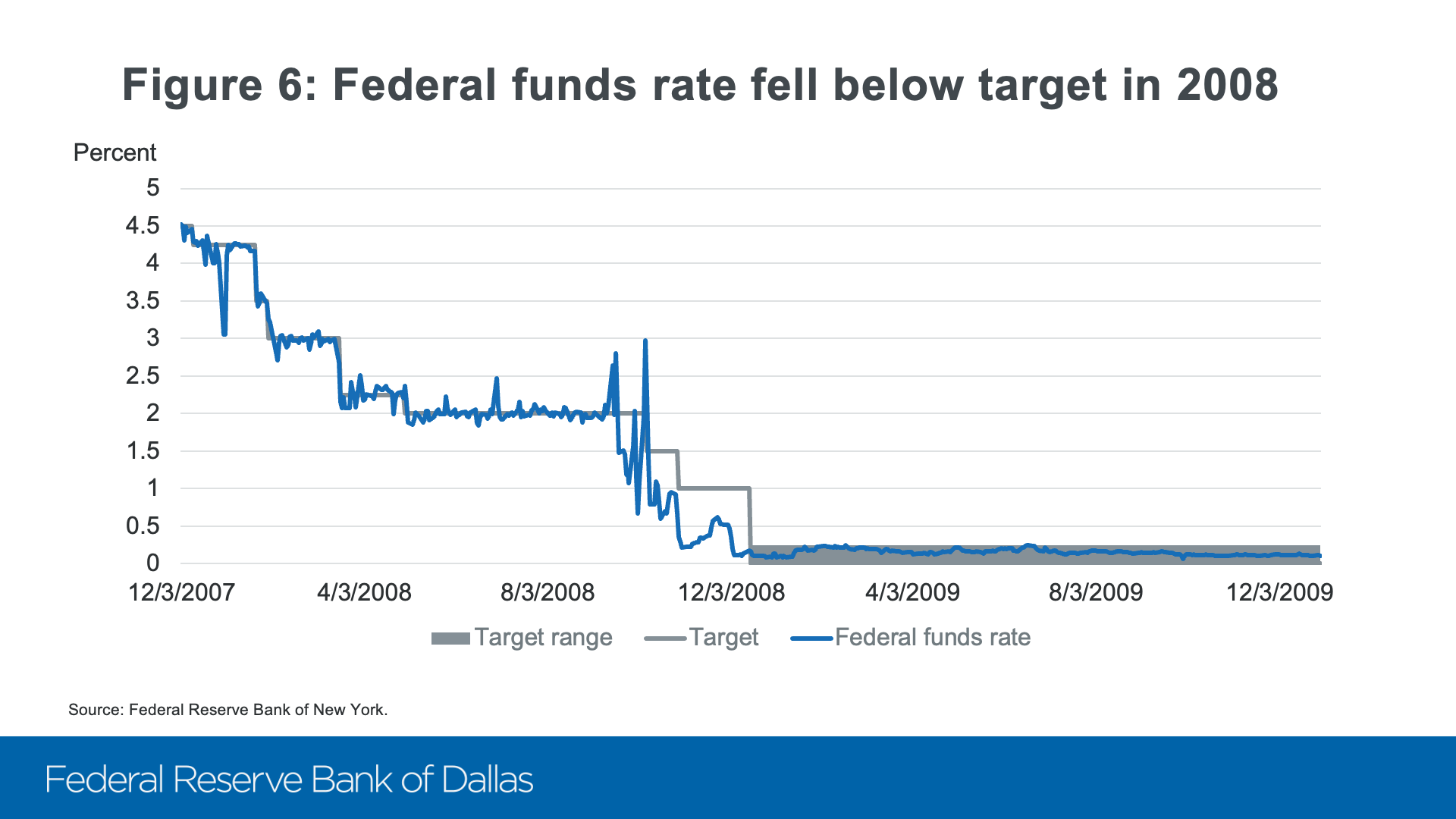

By contrast, when we rapidly expanded our balance sheet in 2008 in response to the Global Financial Crisis, we often saw the fed funds rate trade significantly below the FOMC’s target—even after we began paying interest on reserves, which proved to be only one of the components needed for a well-functioning floor system (Figure 6).[9]

Third, and most closely connected to my theme today, floor systems eliminate what would effectively be a penalty for good liquidity risk management. As I said earlier, reserves are the most liquid asset, bar none. The banking stresses earlier this year proved the unique value of reserves beyond any doubt. Only reserves are immediately liquid. Monetizing any other asset takes time. And sometimes it’s difficult to do at all: counterparties may offer only limited balance sheet space for borrowing against assets, while selling assets can crystallize losses and impair an institution’s health. Holding reserves therefore reduces banks’ liquidity risks relative to holding any other assets.

There are, of course, good reasons for banks to hold assets other than reserves. By making loans, banks provide the credit to households and businesses that is crucial for economic growth. But banks should not pay a penalty for holding reserves when that is the right choice for their liquidity risk management. If the interest rate paid on reserves is meaningfully below money market interest rates, as occurs in a scarce-reserves regime, there is a penalty to banks for managing liquidity well. Floor systems eliminate this penalty and meet banks’ demand for reserves at market prices. This is the sense in which floor systems implement a version of the Friedman rule.

Policy lessons from recent liquidity stress episodes

The question I now want to discuss is: If floor systems do such a good job of reducing the cost of liquidity, why do we keep seeing liquidity stresses? In the U.S., why did severe money market pressures in September 2019 cause some funding rates to spike by hundreds of basis points?[10] Why did the dash for cash challenge markets in 2020, and why did some banks face liquidity stress this past March? And across the Atlantic, what should we make of the liquidity problems that liability-driven investors in the U.K. experienced in 2022?

My answer is that floor systems reduce liquidity risk, but they don’t eliminate it.

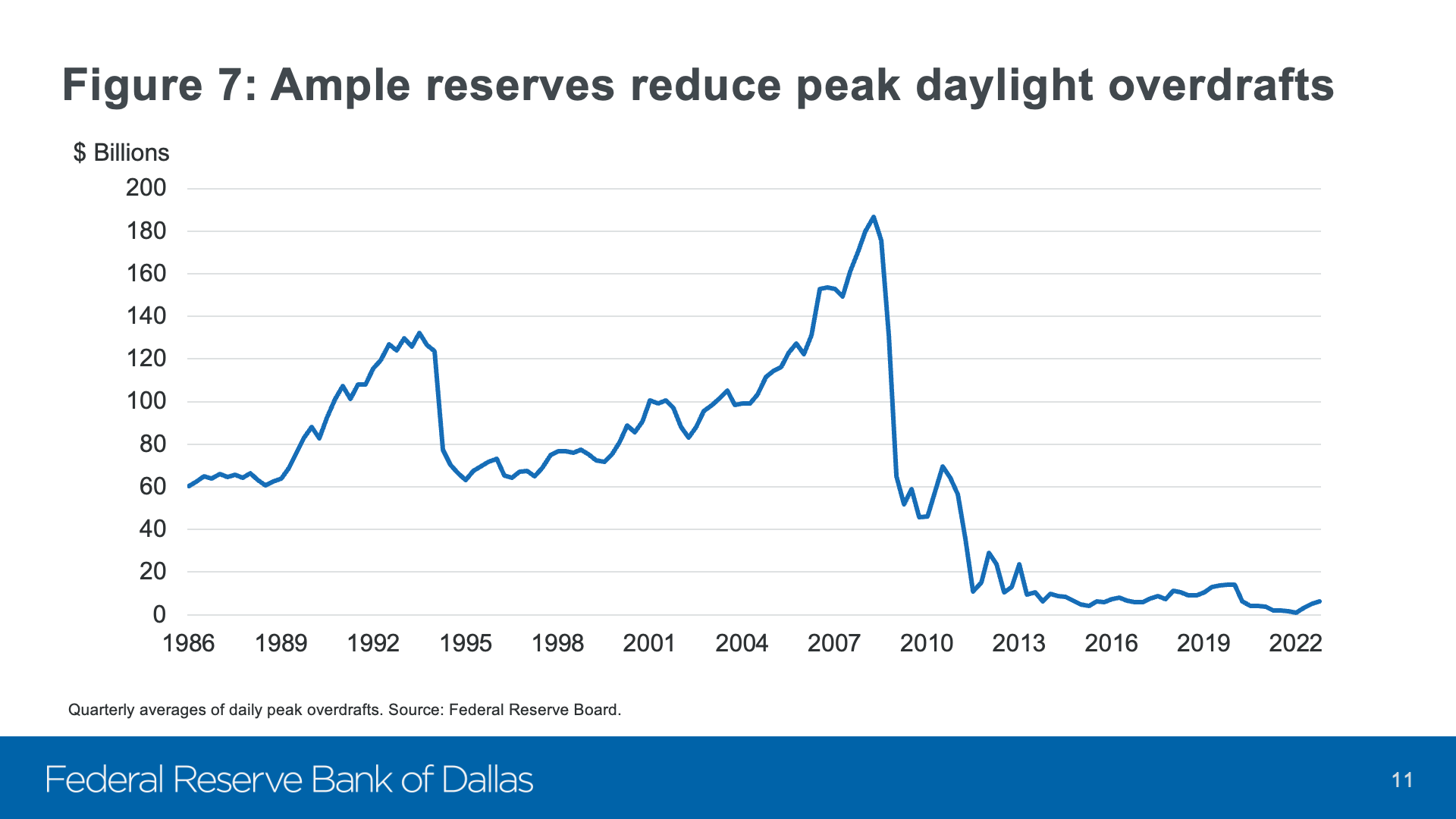

We have seen concrete evidence that liquidity risk is lower in the floor regime. For example, since the Fed moved to a floor system, peak daylight overdrafts are about one-tenth the magnitude seen in the prior regime (Figure 7). And interbank payments are substantially less concentrated at the end of the day because banks are less likely to need to wait to receive incoming payments before making outgoing ones.[11] These are both signs that banks are not seeking to economize on liquidity as much as they used to. The floor regime has reduced the penalty for holding liquidity, as the Friedman rule recommends. So individual banks face less risk of lacking the liquidity needed to make outgoing payments, and the banking system as a whole is less vulnerable to disruptions from payments congestion or shocks late in the day.

Still, there will always be some shocks that a floor system can’t absorb on its own. These can take several forms, including large shifts in the aggregate supply of or demand for reserves; idiosyncratic shocks to individual banks that exceed the system’s capacity to immediately redistribute funds; and shocks to nonbank intermediaries that spill over to bank funding markets. We saw examples of these types of shocks in the liquidity stress episodes I mentioned.

I draw four lessons from these experiences: First, a floor system should include strong backstop ceiling tools. Second, market participants and central banks alike should ensure they are operationally ready to respond to liquidity pressures. Third, regulations should support strong liquidity risk management. And finally, some shocks are too big for any operating regime to absorb easily.

First, ceiling tools. In September 2019, as the Federal Reserve normalized its balance sheet following the expansion during and after the Global Financial Crisis, reserves fell below what we later assessed to be the ample level. It was necessary to add reserves to continue operating a floor system, and that’s what we did. Market data, particularly related to pricing conditions, can help signal when reserves are becoming less ample. But given the uncertainties I discussed earlier, I doubt the risk of reserves falling below the ample level can ever be eliminated, especially if the central bank wants to have an efficient balance sheet with ample but not abundant reserves.

So, as a practical matter, central banks that operate floor systems must be prepared to respond to tail events when reserves fall too low and money market rates can rise above the target level. While discretionary operations such as those we employed in 2019 can effectively address such pressures, a standing ceiling facility at a backstop rate makes a better first line of defense. A standing ceiling facility transparently provides market participants with information about how the central bank will respond and confidence that the central bank will maintain rate control.[12]

In the U.S., we have significantly strengthened our standing ceiling facilities over time. We’ve repeatedly revised discount window policies to make that traditional tool more effective.[13] In addition, in 2021, we established the Standing Repo Facility (SRF) and the Foreign and International Monetary Authorities (FIMA) Repo Facility.[14] These facilities provide liquidity to our counterparties: primary dealers and eligible depository institutions in the SRF and foreign official holders in the FIMA facility.We could study ways to further strengthen our ceiling tools. Such a study could examine how we can take on board the lessons of recent years as well as ongoing changes in the structure of the financial system. For example, the FOMC could further consider the potential benefits of centrally clearing SRF operations.[15] Central clearing could enhance the flow of funding to the broader market by allowing our counterparties to net funding received from the facility against onward lending to other market participants.

Other central banks have considered adding counterparties to their liquidity operations.[16] These choices depend on a central bank’s charter and the financial system in which it operates. In my mind, the focus for the Federal Reserve given our context should be to enhance the effectiveness of operations with our existing counterparties.

Second, operational readiness. One criticism that has been leveled against floor systems is that when liquidity is ample, interbank trading may dry up and banks may become less practiced at sourcing funds when needed.[17] To the extent this happens, I don’t see it as a reason to criticize floor systems. That would be like criticizing modern building codes for reducing the risk of fire. If a city adopts a strong building code, fewer buildings will burn. Residents will have less experience escaping a blaze. Firefighters will have less experience putting out flames. These are good things. And while the lack of experience could have drawbacks, we know what to do about it: fire drills.

Similarly, the lack of daily liquidity challenges doesn’t absolve participants in the financial system from remaining ready should liquidity pressures emerge. A variety of flexible funding sources is available, and even in a floor system in which liquidity is usually ample, banks should be prepared to use these sources. During the banking stresses earlier this year, we found that some banks had not established access to the discount window, had not pre-positioned collateral so they could borrow against it, or had not tested the borrowing procedures. This is unacceptable in an era when bank runs can start in minutes on social media. Ceiling tools won’t work well if financial institutions aren’t prepared to use them.

Every bank in the United States should be fully set up at the discount window as part of its liquidity toolkit. That means setting up legal documents and collateral arrangements well before any funding need arises. And it means testing the plumbing—like a fire drill—so bankers have the muscle memory for borrowing when it’s needed.[18] The same goes for other contingent liquidity sources and for non-bank market participants.

The central bank, too, has a responsibility to maintain operational readiness in a floor system. The Desk regularly tests open market operations to ensure readiness to respond to a variety of potential stresses.

The Federal Reserve should also consider expanding the hours of critical services such as the discount window. With the launch of instant payments services such as FedNow, liquidity in the U.S. and other markets is increasingly a 24/7/365 business. Our liquidity backstop should be available whenever banks may need it. Over time, that could include nights, weekends and holidays, not just business days.

And we should consider how our credit and supervisory policies affect operational readiness. A supervisory or regulatory expectation that depository institutions establish and test access to the discount window could help make individual firms and the financial system more resilient. Periodic testing by all institutions could also reduce the traditional stigmas associated with the discount window. And if we required banks to pre-position some amount of collateral at the window, we could reduce the risk that a bank is unable to borrow because its collateral is in the wrong place.[19]

We could also study ways to make our discount window, a fundamental central bank function, as strong and effective as possible. For example, we could consider the potential benefits of what I would call collateral-based lending. A collateral-based discount window program would lend to legally eligible depository institutions purely on the basis of their collateral.[20] In contrast, the current program of primary and secondary credit varies the terms of lending based on a borrower’s financial condition. Collateral-based discount window lending could strengthen the ceiling by ensuring all eligible institutions have equal access to liquidity against good collateral. It could also improve operational readiness by reducing the need to take time at critical moments to evaluate a borrower’s condition.

I’ll now turn to my third lesson, regulations. Strong regulations are fundamental to a financial system that serves society’s needs. Regulations must also evolve alongside the overall structure of the financial system, the policy implementation framework and the risks that financial institutions face. Regulations that were well suited to a scarce-reserves regime and a world of relatively slow-moving liquidity demands are not necessarily ideal today.

For example, the Basel III leverage ratio counts all of a bank’s assets, including reserves, in the denominator. This rule can raise a bank’s cost of holding reserves and intermediating in funding markets, potentially working against the goal of reducing liquidity risk. Such costs may also add to frictions in the interbank market, reducing the system’s capacity to quickly redistribute liquidity to individual firms that need it.[21] More broadly, it is also important to consider the interactions among regulations, ceiling tools and liquidity risk, including how to ensure that banks are able to use their liquidity buffers and how liquidity regulations account for banks’ access to the discount window and the SRF.[22]

Finally, the fourth lesson: some shocks are just too large. At the onset of the pandemic, market participants had to adapt to a dramatically different global risk environment while shifting to remote work. These developments triggered extraordinary financial market volatility, one-sided trading flows and demands for cash.[23] While improvements in ceiling tools, operational readiness and regulations could conceivably have partially mitigated the stresses, I don’t think any steps could have eliminated the stresses entirely. We should work to ensure the financial system is resilient and central bank intervention to support market functioning is rarely needed. But “rare” does not mean “never.”

In fact, the idea that some shocks are too large for a reasonable operating regime to absorb is built into the Friedman rule framework. The Friedman rule balances the benefits and costs of liquidity. It calls for providing liquidity up to the point that the benefits equal the costs—not for going beyond that point. Conceptually, it would be possible to further reduce liquidity risk by subsidizing banks to hold reserves instead of merely eliminating the interest rate penalty. But such a subsidy would have other costs. So we strike a balance and accept that some shocks will be larger than the regime can absorb without further central bank intervention.

Beyond the Friedman rule: liability-driven and asset-driven floors

That brings me to the costs of supplying reserves and the distinction between liability-driven and asset-driven floor systems. Ordinarily, the policy rate is a central bank’s main monetary policy tool, and the balance sheet plays a supporting role. The Friedman rule describes the optimal quantity of reserves to supply in those normal times: the quantity of reserves that banks demand at market interest rates. Because reserve supply is determined by demand for the central bank’s liabilities, this floor system for ordinary times is called a liability-driven floor. But a central bank may also use its balance sheet more actively in response to deep economic downturns or severe market dysfunction. When a central bank acquires assets for those reasons, it also issues more reserves, creating an asset-driven floor system. In such a system, the amount of reserves is not governed by the Friedman rule—the tradeoff between the liquidity benefits and costs of reserves. Rather, reserve supply in an asset-driven floor is a side effect of the central bank buying assets in response to severe macroeconomic or financial stress.

The Federal Reserve is currently in an asset-driven floor system as a result of our post-pandemic purchases. However, we are running off our asset holdings to return to a liability-driven floor. This is our second such normalization cycle, following the post-GFC normalization of our balance sheet in 2018 and 2019.

Why normalize our balance sheet at all? Why not stick with a higher level of reserves? In my view, there are two reasons to return to ample rather than abundant reserves—in the Friedman rule framework, two costs of supplying reserves above the ample level.[24] First, abundant reserves can distort the price of liquidity for non-bank market participants. And second, while acquiring assets during a severe downturn or in response to severe market dysfunction can provide much-needed support for the financial system and economy, holding the assets too long can undermine the achievement of monetary policy goals. In particular, maintaining overly large asset holdings may push inflation above target or may complicate the calibration and communication of the policy stance, which ordinarily should center on the policy rate.

The first reason is relatively narrow and focuses on money markets. Reserves can be held only by banks (or other institutions eligible for reserve accounts). Other financial institutions must use other instruments, such as Treasury securities, as their liquid assets. By acquiring non-reserve assets to back reserves, the central bank adds to the supply of liquidity for banks but may increase non-banks’ cost of liquidity. But in an efficient system, the costs of liquidity should be similar for banks and non-banks. Significant differences in liquidity costs imply that liquidity is too abundant for one type of firm or too scarce for another.

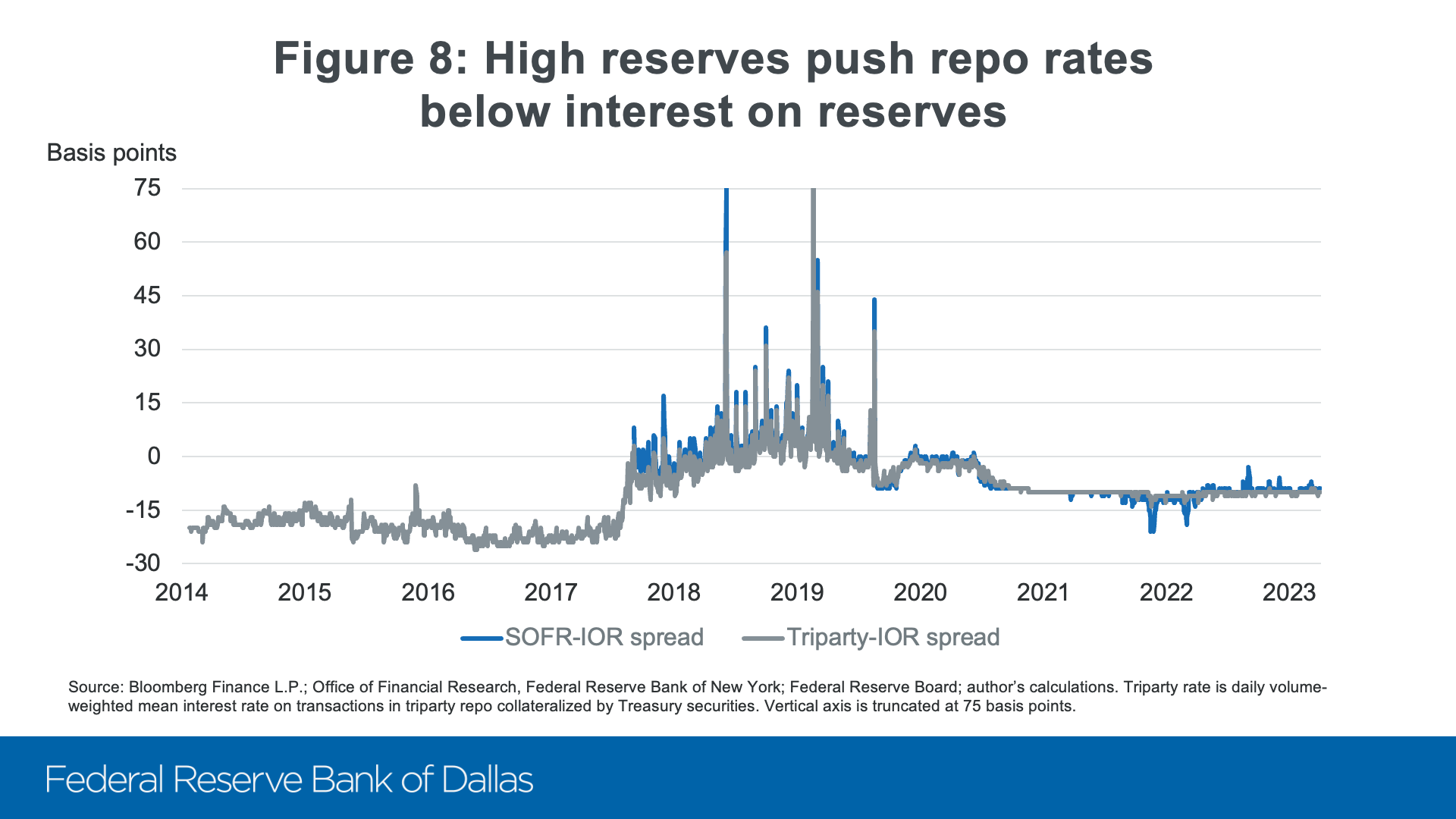

One way to test whether the costs of liquidity are similar for banks and non-banks is to look at money market rate spreads.[25] For example, overnight Treasury repo rates represent the overnight return on a Treasury security. If Treasury repo rates are significantly below the interest rate on reserves, then Treasury securities, the key liquid asset for non-banks, have greater liquidity value than reserves. The Fed’s balance sheet expansions in response to both the Global Financial Crisis and the pandemic pushed repo rates below interest on reserves (Figure 8).

These spreads indicated that liquidity conditions were more abundant for banks than non-banks. In 2018 and 2019, the gap closed as we normalized our balance sheet, and repo rates eventually stabilized a few basis points above interest on reserves. Repo rates and interest on reserves shouldn’t necessarily be exactly equal. There are technical differences between repos and reserves, as well as minor competitive frictions that could introduce a small spread. But in an efficient market, the spread should not be large. This argument is simply the mirror image of the idea that if money market rates are above the interest rate on reserves—if we move up above the floor—there is an undesirable penalty on liquidity for banks.

Some researchers have taken the analysis of relative liquidity costs a step further by estimating the liquidity value of long-term Treasury securities.[26] In such models, the liquidity value of Treasuries includes a negative term premium associated with their flight-to-safety qualities. The central bank’s asset holdings influence that term premium, and one can attempt to calculate the level of asset holdings at which the liquidity value of Treasuries measured in this way would equal the liquidity value of reserves. But I am not persuaded that monetary policy implementation frameworks should be designed around this term premium. To the extent that long-term government debt is scarce, the Treasury can address the scarcity by changing the maturity structure of its debt issuance. When a central bank considers the costs and benefits of supplying more reserves, it should focus on the effects in money markets. Money market conditions reflect the liquidity value of reserves, a unique asset that only the central bank can provide.

The second reason for balance sheet normalization is outside money markets. Expanding the central bank balance sheet and acquiring assets makes setting and communicating the stance of monetary policy more complicated. The central bank must explain its use of two tools—asset purchases and the policy rate—instead of just one. And asset purchases are more difficult to calibrate because their effects are less certain. These challenges are worth surmounting when the policy rate is at the effective lower bound and further stimulus can come only through asset purchases, or when asset purchases are the best available response to threats to financial stability.

But in the absence of such needs, the benefits of higher reserves aren’t commensurate with the drawbacks. Indeed, a large balance sheet can even be counterproductive for our policy goals. The Federal Reserve and other central banks bought large quantities of assets during the pandemic for a reason: to support market functioning, the flow of credit and economic activity in response to a severe economic shock. Circumstances are now different. Financial markets are functioning smoothly. And our primary economic challenge is not a deep recession but rather too-high inflation. In this environment, it is important to remove economic stimulus by returning our assets to the level needed to supply ample—not abundant—reserves.

Conclusion

Central bankers have vigorously debated monetary policy implementation regimes for many years. And I have no doubt we will continue to do so for many more. The Friedman rule offers a useful guidepost in that debate. On the margin, central banks should equate the benefits and costs to society of supplying additional reserves. A floor system with ample reserves satisfies this criterion in my view.

Thank you.

Notes

I am grateful to Sam Schulhofer-Wohl for assistance in preparing these remarks and to Antoine Martin and Patricia Zobel for valuable conversations.

- Milton Friedman, “The Optimum Quantity of Money,” in The Optimum Quantity of Money and Other Essays, Chicago: Aldine, 1969.

- My focus here is on an environment with interest-bearing central bank money (reserves). When money does not bear interest, the Friedman rule also has implications for the optimal inflation rate, which are beyond the scope of this discussion.

- See, for example, Claudio Borio, “Getting up from the floor,” remarks at the Netherlands Bank Workshop “Beyond unconventional policy: Implications for central banks’ operational frameworks,” March 10, 2023.

- Lorie K. Logan, “A Return to Operating with Abundant Reserves,” remarks before the Money Marketeers of New York University, Dec. 1, 2020.

- Lorie K. Logan, “Observations on Implementing Monetary Policy in an Ample-Reserves Regime,” remarks before the Money Marketeers of New York University, April 17, 2019.

- For a formal model, see Gara Afonso, Kyungmin Kim, Antoine Martin, Ed Nosal, Simon Potter and Sam Schulhofer-Wohl, “Monetary Policy Implementation with Ample Reserves,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report No. 910, revised July 2023.

- Lorie K. Logan, “The Federal Reserve’s Market Functioning Purchases: From Supporting to Sustaining,” remarks at SIFMA Webinar, July 15, 2020.

- Lorie K. Logan, “Impact of Abundant Reserves on Money Markets and Policy Implementation,” remarks at SIFMA Webinar, April 15, 2021.

- See “Domestic Open Market Operations During 2008,” report prepared for the Federal Open Market Committee by the Markets Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, January 2009.

- Sam Schulhofer-Wohl, “Understanding recent fluctuations in short-term interest rates,” Chicago Fed Letter No. 423, 2019.

- See, for example, Adam Copeland, Linsey Molloy, and Anya Tarascina, “What Can We Learn from the Timing of Interbank Payments?”, Liberty Street Economics, Feb. 25, 2019.

- For more on principles that should guide central bank interventions to address market dysfunction, see Lorie K. Logan, “Preventing and responding to dysfunction in core markets,” remarks at the Workshop on Market Dysfunction at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, March 3, 2023.

- See James Clouse, “Recent Developments in Discount Window Policy,” Federal Reserve Bulletin, Nov. 1994, 965-977; Brian Madigan and William Nelson, “Proposed Revision to the Federal Reserve's Discount Window Lending Programs,” Federal Reserve Bulletin, July 2002, 313-319; Olivier Armantier, Helene Lee, and Asani Sarkar, “History of Discount Window Stigma,” Liberty Street Economics, Aug. 10, 2015; and Mark Carlson and Jonathan D. Rose, “Stigma and the discount window,” FEDS Notes, Dec. 19, 2017.

- Federal Open Market Committee, “Statement Regarding Repurchase Agreement Arrangements,” July 28, 2021.

- See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee, June 15-16, 2021,” 2021.

- See Andrew Hauser, “A journey of 1000 miles begins with a single step: filling gaps in the central bank liquidity toolkit,” speech at a Market News International Connect Event, Charter Accountants’ Hall, London, Sept. 28, 2023.

- For additional discussion of interbank trading in different implementation regimes, see Simon Potter, “Discussion of ‘Evaluating Monetary Policy Operational Frameworks’ by Ulrich Bindseil,” remarks at the Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium, Aug. 26, 2016.

- See Lorie K. Logan, “Remarks on liquidity provision and on the economic outlook and monetary policy,” remarks to the Texas Bankers Association, San Antonio, May 18, 2023.

- For a discussion of frictions in collateral movement during the March 2023 banking stresses, see Richard Ostrander, “Remarks on the Panel ‘Bank Crisis Framework: Learning from Experience,’” Paris Meeting of the Committee on International Monetary Law of the International Law Association, June 17, 2023.

- In the U.S., the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991 limits discount window lending to undercapitalized depository institutions.

- See Kyungmin Kim, Antoine Martin and Ed Nosal, “Can the interbank market be revived?”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 52(7), 1645-1689, October 2020.

- See Randal K. Quarles, “The Economic Outlook, Monetary Policy, and the Demand for Reserves,” speech at the Money Marketeers of New York University, Feb. 6, 2020.

- Lorie K. Logan, “Treasury Market Liquidity and Early Lessons from the Pandemic Shock,” remarks at Brookings-Chicago Booth Task Force on Financial Stability meeting, Oct. 23, 2020.

- A central bank’s charter and the financial system in which it operates may also influence the considerations surrounding the optimal supply of reserves. For a discussion of these and other factors in the U.K. context, see Andrew Hauser, “‘Less is more or’ or ‘Less is a bore’? Re-calibrating the role of central bank reserves,” speech at Kings College London’s Bank of England Watchers’ Conference, Nov. 3, 2023.

- See, for example, Darrell Duffie and Arvind Krishnamurthy, “Pass-Through Efficiency in the Fed’s New Monetary Policy Setting,” paper presented at the Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium, Aug. 26, 2016, and Simon Potter, “Money Markets at a Crossroads: Policy Implementation at a Time of Structural Change,” remarks at the Master of Applied Economics’ Distinguished Speaker Series, University of California, Los Angeles, April 5, 2017.

- See Annette Vissing-Jørgensen, “Balance Sheet Policy Above the ELB,” paper presented at the ECB Forum on Central Banking, June 28, 2023.

The views expressed are my own and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve System.