Pandemic painful for many self-employed women, but their numbers are rising again

Years before the term “she-cession” became part of our national lexicon, the number of businesses owned by women was growing at a rate more than twice that of all businesses. In 2019, women-owned firms represented 42 percent of all businesses—a drastic increase from fewer than 5 percent in 1972—and generated $1.9 trillion in revenue.[1]

This growth occurred even though women-owned firms did not always enjoy equal access to capital and credit. Research indicates that small firms owned by women have historically struggled with lower credit scores, more financial challenges and larger funding gaps on average than firms owned by men.

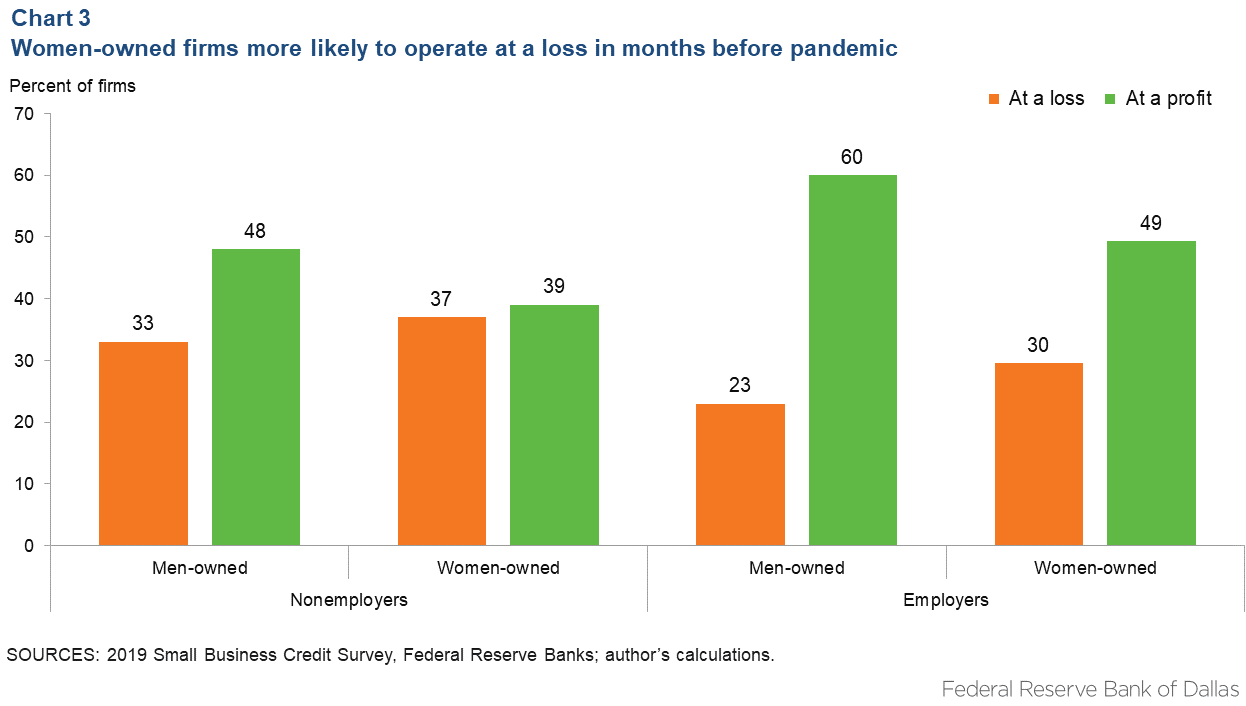

It’s no surprise that despite their increasing importance to the economy, women-owned firms were less likely than firms owned by men to be financially healthy heading into the COVID-19 economic crisis.[2] More than one-third of small women-owned firms were financially at risk or distressed before the pandemic, compared with 28 percent of men-owned firms. This left small firms owned by women more vulnerable to the economic shock brought on by the pandemic.

In this series, we will explore trends in female self-employment, provide an overview of challenges and disparities for women-owned firms, and look ahead to expectations for women-owned small businesses in the U.S. and Texas. We begin with a look at self-employment before and after the pandemic.

Although reliable and timely data on small business ownership are scarce, we can estimate the number of working business owners—both employers and nonemployers—by looking at Current Population Survey (CPS) data.

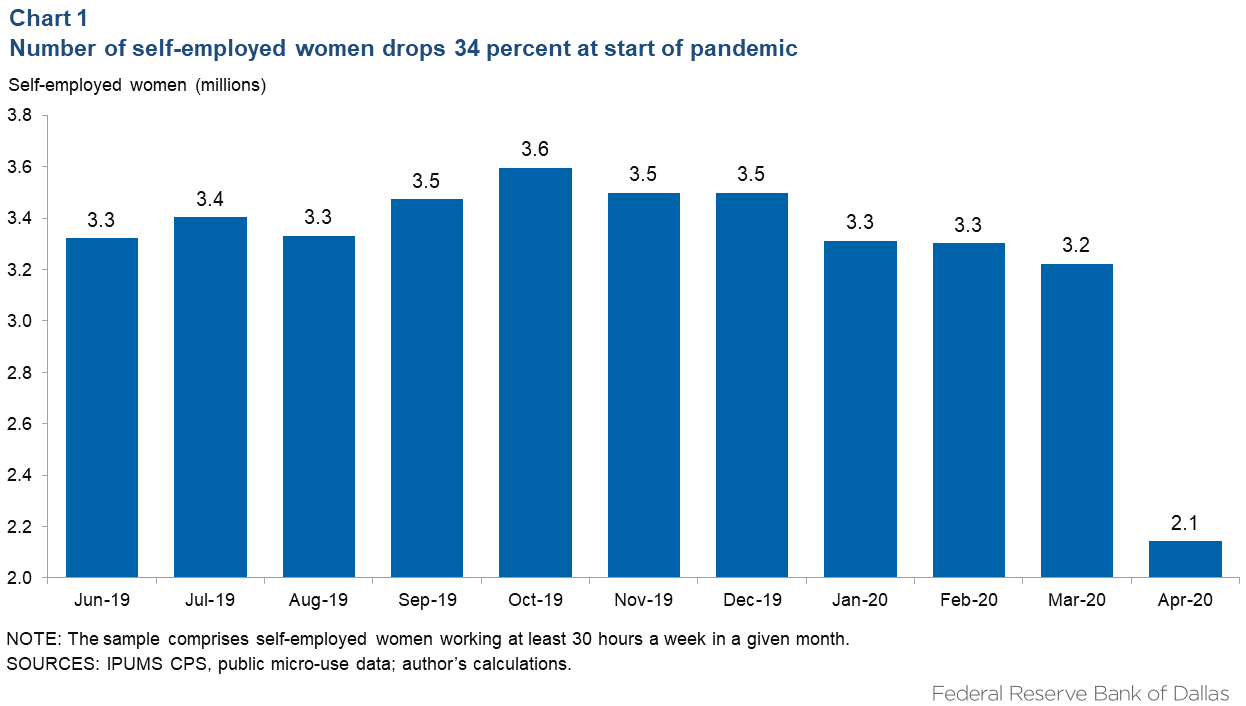

We can see the initial pandemic trends play out: In the early months of COVID-19, the number of self-employed people who reported working at least one hour a week dropped from 15.0 million to 11.7 million. Looking at self-employed workers devoting at least 30 hours a week to their business—which we use to roughly estimate a near-full-time workload—the drop-offs were larger. The number of self-employed men working at least 30 hours fell 22.6 percent, from 7.2 million in March 2020 to 5.5 million in April 2020. The number of self-employed women tumbled 34 percent, from 3.2 million to 2.1 million (Chart 1).

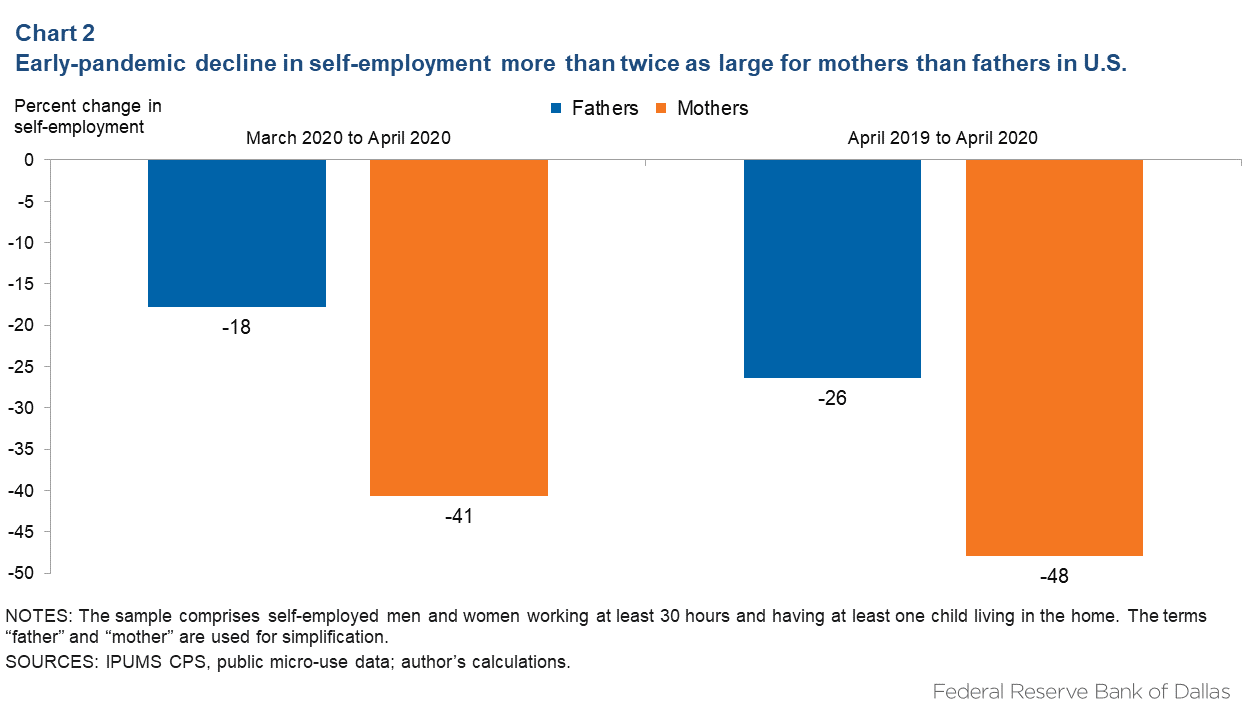

We also explored the impact of family dynamics on self-employment among those who were working at least 30 hours a week, given that school and day care closures were widespread in the early months of COVID-19. Chart 2 shows the percent change in self-employment for men and women with at least one child in the household.

Self-employed mothers working at least 30 hours per week saw an especially large decline as COVID-19 struck. Their employment fell by more than 40 percent in one month, March to April 2020, while the decline for fathers was a smaller though still-historically large 18 percent. Year over year, the decline in self-employment for women with children was close to 50 percent, compared with a drop of 26 percent for men.

Several factors likely contributed to these disparities. For one, child care burdens in the United States fall disproportionately on women, which means that self-employed mothers were more likely than fathers to take time off to focus on at-home schooling. For another, women-owned firms were more likely than those owned by men to be in a financially precarious position prior to the pandemic (Chart 3).

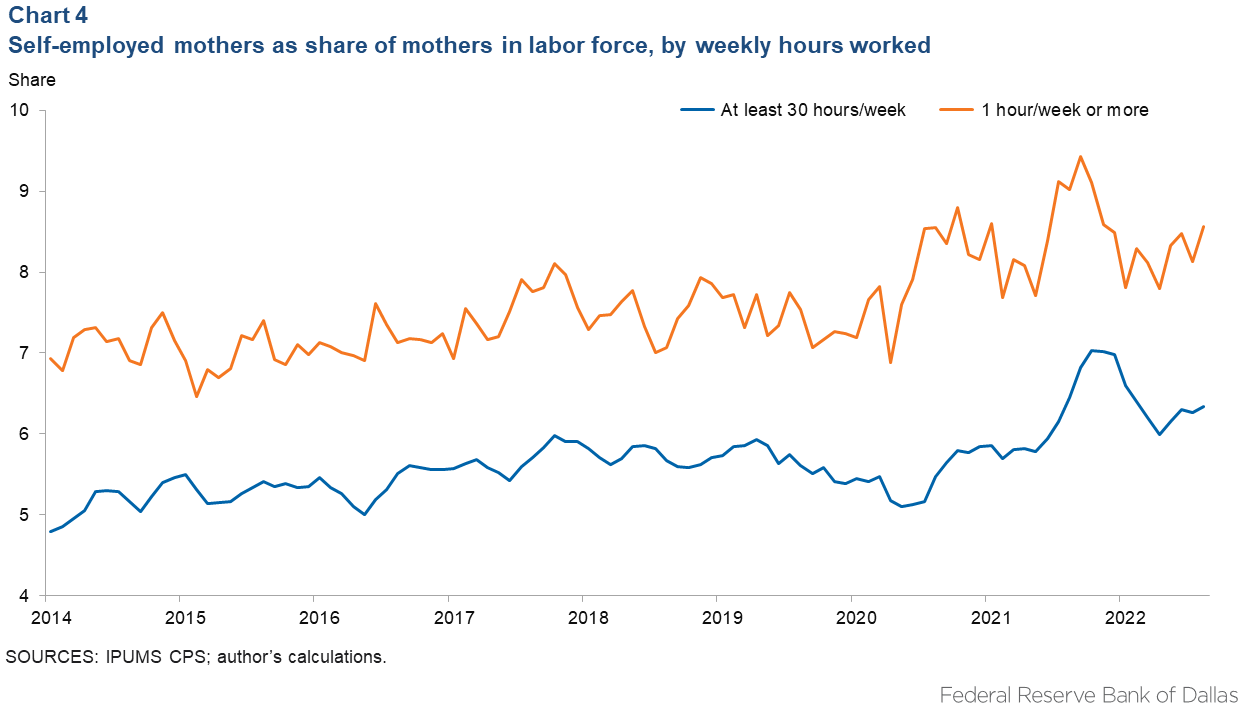

Although this decline was stark, it was also temporary. Four-month moving averages for both self-employed men and women working at least 30 hours a week indicate that the number of self-employed individuals in the labor force rose substantially in the months that followed, surpassing prepandemic levels in the third quarter of 2022. In particular, the number of self-employed women with children in August 2022 stood 8 percent above where it had been in January 2020. For men with children, the numbers did not change over that time.

Self-employment trends over a longer time horizon of the past eight years show that the number of self-employed mothers has risen as a share of all mothers in the labor force. As Chart 4 indicates, more than 9 percent of all mothers in the labor force are self-employed.

This growth is not contained just to mothers. In fact, at slightly under 40 percent, women represent a growing share of the self-employed in the country (37 percent) and in Texas (39 percent). This is up from 34 percent and 32 percent, respectively, in 2016.

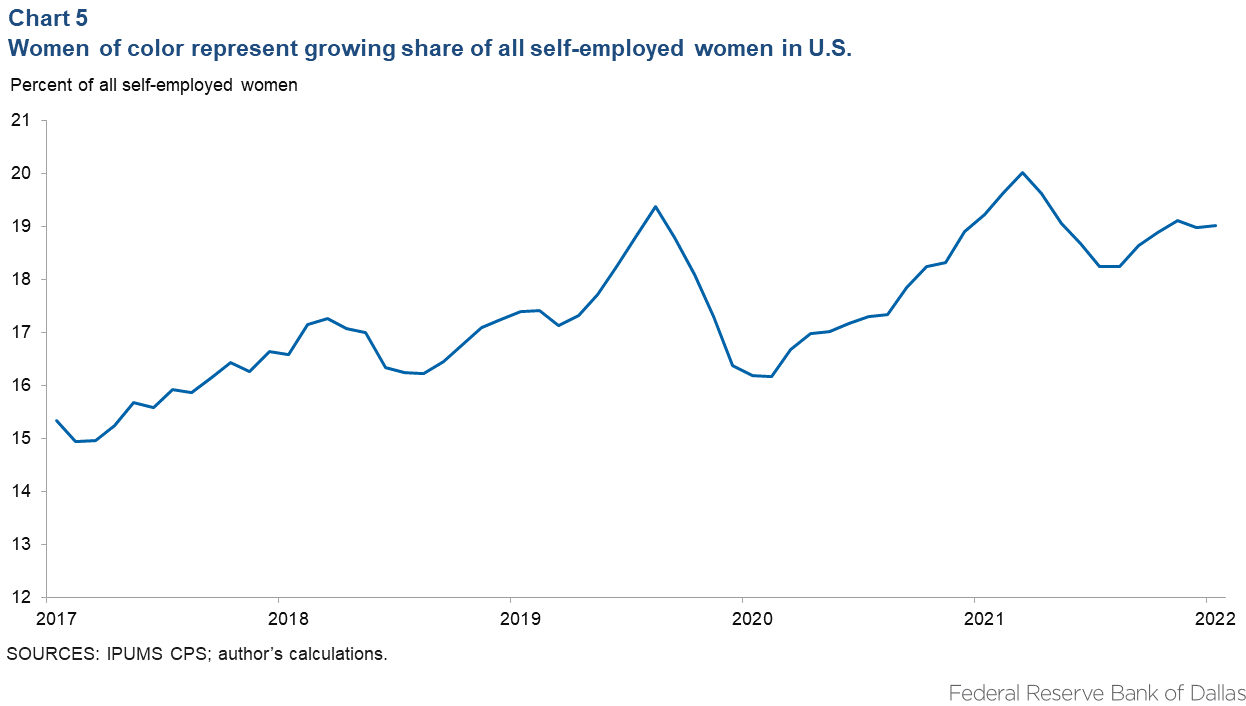

Women of color, in particular, make up an increasing share of all self-employed women.[3] Chart 5 shows their overall representation rose from 15 percent to nearly 20 percent over the five years through 2022. Other studies have suggested women of color are opening businesses at 4.5 times the average rate.

As the rate of self-employment grows for all women, and especially for those of color, their businesses will have an increasingly large impact on the economy. It makes sense, therefore, to better understand the specific barriers and challenges women-owned businesses face. This is particularly important in Texas, where women of color represent a larger share of the overall population and of small business owners than in other states.[4]

The second part of this series will explore Texas-specific findings from the Federal Reserve’s Small Business Credit Survey, with an emphasis on women-owned employer firms and firms owned by women of color.

Notes

- These businesses include all nonemployer and employer firms. Employer firms are those that employ at least one person other than the business owner.

- Healthy firms are defined as those that meet the following criteria: 1) profitable; 2) high credit score; 3) use retained business earnings to fund the business. At-risk firms meet only one of the three criteria, and distressed ones meet none. See “Can Small Firms Weather the Economic Effects of COVID-19?” by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, April 2020, Fed Small Business Survey & Reports.

- Women of color include women who are Black, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, or two or more races.

- 2023 Report on Employer Firms: Findings from the 2022 Small Business Credit Survey, 2023 Small Business Credit Survey, Federal Reserve Banks.

About the author