Employment numbers suggest young people face barriers in recovery from pandemic

Part 2 | Part 3

The years 16–24 are crucial for the development of human capital—through activities such as education and workforce preparation that pay dividends in the form of higher wages, lower unemployment and other benefits later in life. Yet even before the pandemic, many young people were disconnected from school and work and the economic opportunities that follow. In 2019, the Dallas Fed’s report on these “opportunity youth” in Texas estimated there were nearly half a million in the state.

To foster an inclusive recovery, it’s important to understand how many young people are still disconnected from school and work and how to improve opportunities for them to reconnect. This will not only help individuals in the short run, it will help the economy grow overall by reducing public expenditures (such as those related to poverty and crime) and setting up future generations for success.

In this series, we’ll examine whether opportunity youth numbers have increased during the pandemic, as some experts fear, and what could be done to correct this trend. We’ll begin with a look at employment.

National youth unemployment

Historically, the youth unemployment rate is higher than that of the older population. To get a picture of whether that remained true during the early months of COVID-19 and what has changed since, it’s instructive to look at monthly unemployment rates for teenagers and young adults over the last few years.

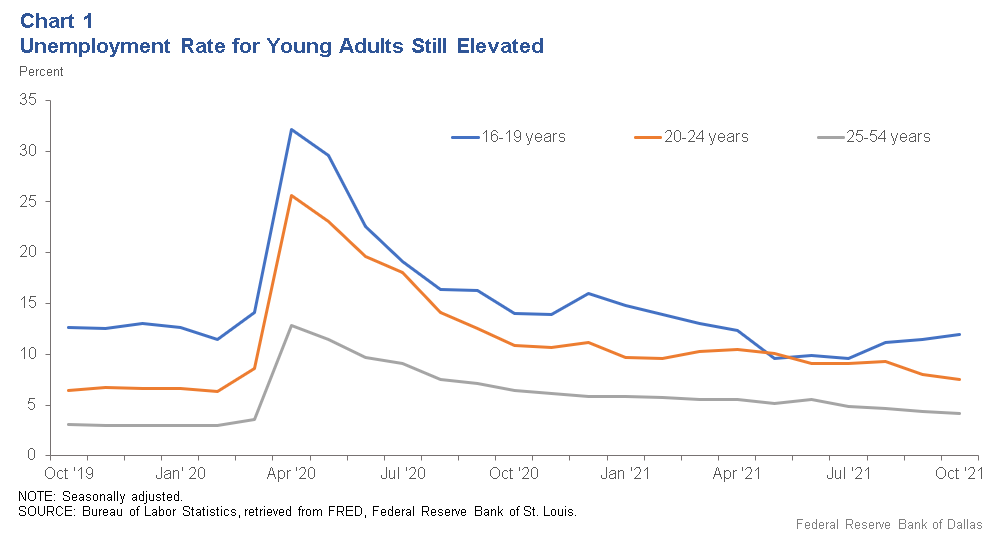

Chart 1 shows the unemployment rate for 16–19-year-olds, 20–24-year-olds and 25–54-year-olds (prime-age workers). Coming into the pandemic, the unemployment rate averaged 6.6 percent for young adults aged 20-24 between August 2019 and February 2020, compared with 3.0 percent for adults 25-54. The rate for teenagers aged 16-19 was higher still, averaging 12.4 percent during those months.

The pandemic caused unemployment to spike for all workers, but some age groups have returned to prepandemic rates faster than others. Since May 2021, the teenage unemployment rate has generally been lower than it was prepandemic (this has a potential downside). However, the unemployment rate for 20–24-year-olds in October 2021 was 1.1 percentage points higher than its October 2019 level of 6.4 percent. For purposes of comparison, the unemployment rate for 25–54-year-olds was also 1.1 percentage points above its October 2019 level of 3.1 percent.

Young adults’ slow return to labor force

The unemployment rate only tells part of the story, though. A number of youths (and older adults) have dropped out of the labor force entirely and hence aren’t counted for unemployment.

To estimate how many young people have given up on looking for work, we look to the labor force participation rate—the share of the population that is either employed or out of work but actively seeking employment. A drop in the rate since before the pandemic would indicate that more people have chosen to leave the labor force.

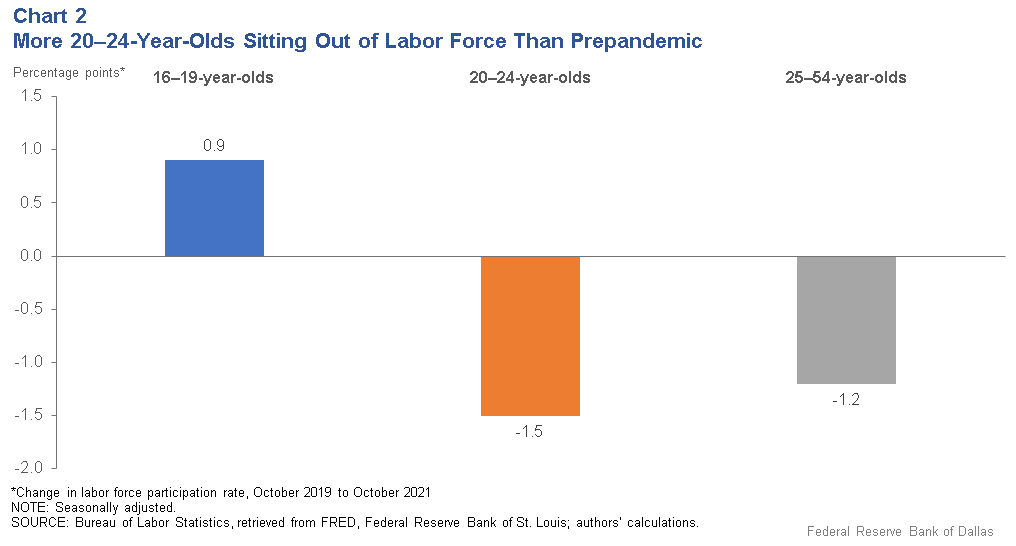

Chart 2 shows the change in labor force participation rate between October 2019 and October 2021. In October 2019, the labor force participation rate for 20–24-year-olds was 72.8 percent. In October 2021, the rate was 71.3 percent. This decline exceeds that of the older adult population, whose labor force participation rate fell by 1.2 percentage points during the same period.

Teenagers, in contrast, have surpassed their October 2019 labor force participation rate of 35.5 percent, with the October 2021 rate for 16–19-year-olds 0.9 percentage points higher. For this reason, we mainly focus the remainder of our analysis on 20–24-year-olds.

Possible reasons for disconnection

What is happening for young people, mostly in the 20–24-year-old age range, who have left the labor force since the pandemic began? In theory, it’s possible that some have chosen to enroll in school rather than seek employment. However, declining community college enrollment in the post-COVID era suggests that other factors are responsible for this phenomenon.

There are several potential reasons why a large number of individuals in this age group have stopped working or seeking work. One is that they may have experienced labor market “scarring” and seen their skill sets erode to the point where they can no longer find work for the wage they used to receive. Another possibility is that COVID-era safety nets were sufficiently generous that some individuals may have been incentivized not to work. A third is that young adults may have been disproportionately pulled into elder care or child care responsibilities.

Gaining a better understanding of why 20–24-year-olds have left the labor force is critical to understanding what will happen in the future. If the main reason is generous safety nets, then their removal would be expected to raise young-adult labor force participation relatively quickly. But if the main reason is that labor market scarring is particularly acute among this population, then we’d expect young-adult labor force participation to remain above prepandemic levels for some time. And if it is caregiving, then the pace of improvement would depend on COVID caseload trends and potentially also child care policy changes at the state or national level.

Disconnection and employment by race, gender and geography

Broadly speaking, there is some overlap between the demographic groups that are historically more likely to be opportunity youth and those hardest hit during the pandemic-induced recession.

Our 2019 report on opportunity youth in Texas highlighted differences in youth disconnection rates by race, gender and geography. We found that Black and Hispanic youth are overrepresented among Texas’ opportunity youth while girls and young women, especially those who are Black or Hispanic, are slightly overrepresented. We also found that, consistent with national trends, some rural areas in Texas have especially high disconnection rates among their young people.

During the pandemic, some of these same demographic groups struggled more with job loss. Nationally, Black and Hispanic women have seen the biggest drop in labor force participation rates compared with other race and gender groups. And some of the hardest-hit Texas counties in terms of unemployment were rural counties. This was most apparent in Deep East Texas and in South Texas, two areas we explored in our 2019 report.

Fostering an inclusive recovery

Unemployment rates spiked for young adults in the initial months of the COVID recession. Since that time, younger members of this cohort (ages 16-19) have substantially recovered, while older members (ages 20-24) continue to see unemployment rates well above pre-COVID levels. Moreover, the demographic groups that have seen the largest employment setbacks tend to be those with higher rates of disconnection in the first place. Because studies have shown disconnection today leads to lower incomes down the road, the risk of many more young people in the U.S. experiencing longer-term disconnection from workforce opportunities is a concern.

To support an inclusive economic recovery, it is critical that we not overlook youth and the continued obstacles they face to employment.

The next story in this series will explore how school closures and remote learning may also be contributing to an increase in opportunity youth.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.