Weathering the Storm: A Framework for Meeting CRA Obligations

The purpose of this publication is to provide financial institutions:

- A brief overview of disaster recovery and its connection to the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA)

- A framework as to how financial institutions can qualify disaster-recovery activities under the CRA

- A roadmap of how to identify opportunities that can help communities weather future storms

- A template for financial institutions to tell their CRA story, highlighting lending, investments and services that are responsive to the needs of their assessment areas

- Appendixes of CRA and disaster-recovery resources for additional information regarding disaster-related opportunities in their assessment areas

Part One: Disaster Recovery in the United States

Over the past decade, the dialogue surrounding disaster recovery has shifted from “if” the storm is coming to “when” as countless communities across the U.S. have seen a surge in the number of natural disasters they face. In the past, such catastrophic events occurred roughly once a decade on average, providing communities with what some might deem adequate time to recover. But in recent years, there has been an uptick in the frequency and the severity of natural weather events.[1]

Wildfires in California, like this one near Santa Clarita in 2016, can have an economic impact that reaches beyond the geographic area.

Wildfires in California, like this one near Santa Clarita in 2016, can have an economic impact that reaches beyond the geographic area.In 2017 alone, natural disasters across the southern United States directly impacted Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Florida as well as the U.S. territories of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. These disasters left in their wake billions of dollars in physical damage, stifling major industries and shutting down countless small businesses. In California, wildfires devastated nearly a dozen counties, compounding the effect of natural disasters on the U.S. economy.

Across the U.S., many regions have been especially hard hit by recent hurricanes, tropical storms, wildfires, tornadoes, floods and other weather events. For the southern and eastern regions of the nation, the months of June through November (commonly referred to as hurricane season) now bring great uncertainty each year and leave many bracing for the worst.

The economic impact of these catastrophic events cannot be overlooked. Since 1980, the United States has experienced 230 major climate- and weather-related disasters that have produced more than $1.5 trillion in overall damages.[2] The effects of any natural disaster are usually widespread, influencing major industries, small businesses, communities, families and individuals—and often creating outsized hardships for low- and moderate-income (LMI) residents.

Further, the nation’s economic interdependence on industry clusters in vulnerable regions, such as oil and gas along the hurricane-prone Gulf Coast, reinforces the need for additional national dialogue on investment opportunities related to disaster preparedness and recovery. The Gulf Coast region is home to many of the nation’s fastest-growing cities, including Houston, the nation’s fourth-largest city and a leader in the energy and health care industries.[3] Along with hurricanes, this area is particularly vulnerable to flooding and tornadoes. Past natural disasters in the region have presented significant economic challenges for the U.S., including increased costs for oil refining, natural gas, gasoline and plastics production.

Another example of this interdependence can be found in the Silicon Valley region of Northern California, which is vulnerable to earthquakes and wildfires. This region serves as an epicenter for many of the world’s leading tech companies and has long stood as a major source of technological innovation within countless industries. Consequently, while the physical damage from a natural disaster striking this region might be geographically restricted, the potential economic impacts could have a far greater reach given the global importance of the region’s technology sector.

Hurricane Harvey brought widespread flooding to the Houston region in 2017, crippling the Texas Medical Center, one of the world’s leading health care facilities.

Hurricane Harvey brought widespread flooding to the Houston region in 2017, crippling the Texas Medical Center, one of the world’s leading health care facilities.Many other regions of the country serve as centers for jobs critical to the U.S. economy. And no community is exempt from the forces of Mother Nature, whether located in a disaster-prone region or not. Moreover, even when natural disasters appear to be geographically limited in scope, their economic impact is felt more broadly across the nation. This reinforces the idea that disaster recovery is the shared responsibility of all.

The Funding Challenge

Moody Analytics estimates that direct damage caused by Hurricane Harvey will range from $60 billion to $70 billion, and—as with other natural disasters—it is unlikely that the federal government and/or private insurance will cover the entire cost.[4] A survey of federal assistance during past hurricane events since Hurricane Katrina in 2005 reveals that, on average, the U.S. government has contributed funds to cover approximately 60 percent of estimated damages following these storms.[5] According to the Congressional Research Service, this federal spending average includes dollars from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) disaster relief fund and National Flood Insurance Program, Small Business Administration disaster lending programs, Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Community Development Block Grants and other federal agency programs.

The table below shows the estimated economic impact of major storms since Hurricane Katrina and the federal government dollars spent following each disaster. Removing hurricanes Sandy and Katrina—two outliers that received unusually high levels of federal aid in comparison to other storms—drops the average covered by federal aid from roughly 62 percent to 37 percent. Based on the table’s historical data, it seems clear that federal aid will likely not cover the total economic cost of the 2017 hurricanes that impacted many parts of the southeastern United States.

|

Federal Government Hurricane Recovery Dollars |

||||

| Year | Hurricane name (impacted areas) |

Estimated damage (in billions) |

Estimated federal spending (in billions) |

Percent covered |

| 2005 | Katrina (FL, LA, MS) | 160 | 114.5 | 72 |

| 2005 | Rita (TX, LA) | 23.7 | 9 | 38 |

| 2005 | Wilma (FL) | 24.3 | 6.4 | 26 |

| 2008 | Dolly (TX) | 1.51 | 302 million | 20 |

| 2008 | Gustav (LA) | 6.9 | 4.1 | 60 |

| 2008 | Ike (TX, LA) | 34.8 | 12.8 | 37 |

| 2011 | Irene (NC) | 15 | 4.5 | 30 |

| 2012 | Isaac (LA) | 2.35 | 1.1 | 47 |

| 2012 | Sandy (NJ, NY, MA) | 70.2 | 56 | 80 |

| 2016 | Matthew (FL, GA, SC, NC) | 10.3 | — | — |

| 2017 | Harvey (TX, LA) | 125 | — | — |

| 2017 | Irma (FL, VI) | 50 | — | — |

| 2017 | Maria (PR, VI) | 90 | — | — |

| NOTES: All amounts have been converted to 2017 dollars per the Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI Inflation Calculator. Federal spending totals for Matthew, Harvey, Irma and Maria are not yet available due to the recency of the storms. SOURCES: Congressional Budget Office; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Hurricane Center. |

||||

It is important to note that federal aid is not the primary mechanism by which communities are expected to recover. Federal aid predominantly focuses on meeting “unmet needs”—those likely to remain unaddressed after funding from all other sources has been accounted for.

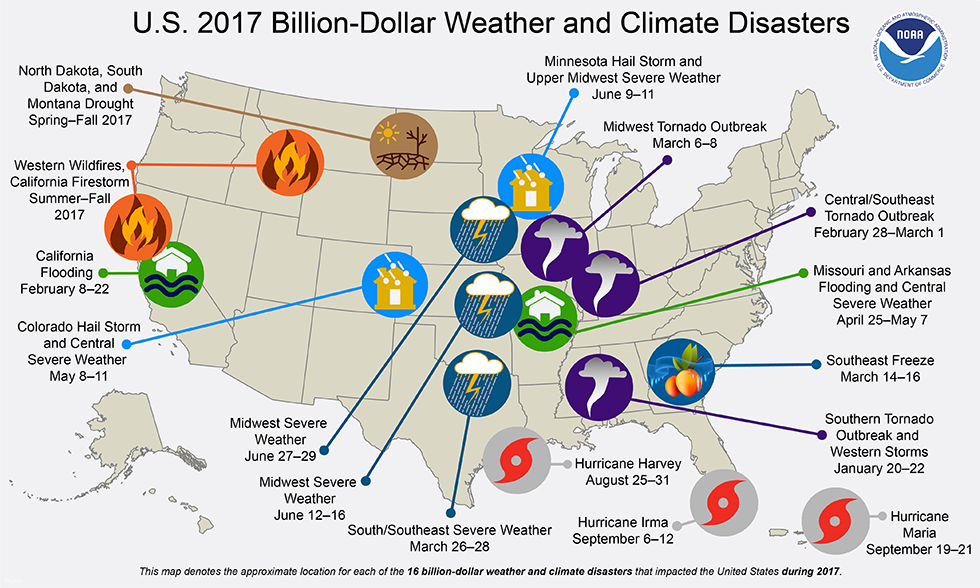

In 2017, the United States experienced an unprecedented level of catastrophic natural weather events: three hurricanes in the southern U.S., numerous wildfires across Northern California, tornadoes throughout the Midwest and Southeast, hailstorms in Colorado and Minnesota, a prolonged drought in North and South Dakota as well as Montana, and deep-freeze and severe flooding events in the Midwest and Southeast. According to a January 2018 report released by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), natural disasters across the U.S. in 2017 caused more than $306 billion in damage and set a U.S. annual record.[6] Federal aid is likely to be stretched thin as the nation seeks to recover using limited resources.

2017 brought widespread weather and climate disasters to the U.S., emphasizing the need for additional discussion on this topic nationally. Credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

2017 brought widespread weather and climate disasters to the U.S., emphasizing the need for additional discussion on this topic nationally. Credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric AdministrationWith federal aid expected to cover only a portion of the economic costs associated with the 2017 natural disasters, the complete recovery of impacted communities will largely lie in the hands of entities that have access to capital. Moreover, long-term federal aid is often slow to arrive due to the lengthy appropriations process, which further delays the recovery of affected regions. In many instances, it has taken this form of federal aid more than a year to arrive.

For many individuals impacted by a natural disaster, this waiting period is the most critical in the disaster-recovery process, and most of those affected cannot afford to wait on federal aid to begin rebuilding their lives. They need access to adequate resources that all too often are not immediately available. Ultimately, these individuals will look to local and state governments, which often are also waiting on federal assistance and other disaster-related benefits. In this situation, finding access to adequate, flexible and affordable capital is of paramount importance if communities are to engage in responsive disaster-recovery efforts.

According to FEMA, roughly 40 percent of small businesses close permanently following a disaster.[7] Furthermore, many small businesses located in FEMA-designated disaster areas hold insurance that is mismatched to the types of damage experienced, leaving substantial revenue losses and sizable funding gaps.[8] A 2017 Federal Reserve study found that, while 65 percent of affected firms pointed to loss of power or utilities as the major source of their losses, only 17 percent held business-disruption insurance.

Additionally, as Hurricane Harvey revealed, many households lack adequate flood insurance to protect their losses. According to estimates, more than 80 percent of homeowners in the eight Texas counties most heavily impacted did not have flood insurance under the National Flood Insurance Program, which would have covered up to $250,000 in rebuilding costs and $100,000 in personal contents.[9]

Statistics like these make it clear that many individuals, families and small businesses are not prepared to weather catastrophic storms—and for those affected, access to capital that banks can provide during disaster-recovery periods can mean the difference between rebuilding and receiving a new start or not.

| The Community Reinvestment Act |

First enacted in 1977, the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) encourages depository institutions to help meet the credit needs of the communities in which they maintain banking operations, consistent with safe and sound operations. CRA was not created to encourage banks to engage in more risky lending and investment practices. It is important to remember that banking activities, whether subject to CRA or not, must still be consistent with safe and sound banking practices. The expansion of CRA has not occurred overnight or by coincidence. The regulatory agencies with CRA responsibilities provide guidance to agency staff, financial institutions and the public through the Interagency Questions and Answers Regarding Community Reinvestment (Q&As). The agencies have updated the Q&As periodically, with the most recent guidance released in 2016. Among the topics addressed in the Q&As are activities that revitalize or stabilize designated disaster areas and investments in community development financial institutions (CDFIs), broadband access and workforce development. |

Banks are important players in the disaster-recovery process because they are uniquely situated to offer assistance during this precarious time, given their compliance requirements under the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) as well as their pursuit to be good corporate citizens. The CRA provides a meaningful opportunity for bankers to help affected communities recover after natural disasters as well as stimulate local economies through lending, investments and services that stabilize and revitalize neighborhoods, promote economic and small-business development, repair deteriorating infrastructure and create long-term employment opportunities for all, including LMI individuals.

Private industry and philanthropy also play a role in helping communities return to their pre-disaster levels. For private industry, it makes good business sense to invest in recovery because these communities provide the human capital necessary to their business needs as well as a consumer base for selling goods and services and generating revenue and profits. For philanthropy, supporting recovery is simply the right thing to do. Philanthropic organizations are usually mission driven and able to assist in the rebuilding of communities and lives when there are either no resources available or when other entities do not make adequate investments in affected communities.

| Four Types of Activities Considered to Be Community Development1 |

Notes

|

Notes

- See the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory’s overview on global warming and hurricanes.

- For more information regarding historical natural disaster damage totals for the U.S. as well as natural disaster damage for 2018, see NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) 2018 report “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters.”

- See “The Census Bureau Shows the Fastest-Growing Cities in the U.S. Are …,” by Mary Bowerman, USA Today, May 26, 2017.

- For more information on measuring the impact of Hurricane Harvey, see the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas’ 2017 Annual Report.

- For more on federal government hurricane assistance spending, see “What Past Federal Aid Tells Us About Money for Harvey Recovery,” by Ryan Struyk, CNN News, Sept. 7, 2017.

- For more information on the damage caused by 2017 natural disasters in the U.S., see NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information 2017 report “2017 was 3rd warmest year on record for U.S.,” Jan. 8, 2018.

- For more on small-business outlooks following disasters, see “Hurricane Alert: 40 Percent of Small Businesses Never Recover from a Disaster,” by Chris Morris, CNBC, Sept. 16, 2017,

- “Small Business Credit Survey Report on Disaster-Affected Firms,” Federal Reserve Banks of Dallas, New York, Richmond and San Francisco, April 2017.

- “Where Harvey Is Hitting Hardest, 80 Percent Lack Flood Insurance,” by Heather Long, Washington Post, Aug. 29, 2017.

Next: Part Two: How a Bank’s Activities in Disaster Recovery Can Fit CRA Criteria »

Author

- Kevin Dancy

Contributors

- Pamela Foster

Communications Partner, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas - Kathy Thacker

Editor, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

Special thanks to the staff of the Division of Consumer and Community Affairs at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors and the Consumer Affairs group of the Dallas Fed’s Banking Supervision Department for their input in the review process of this publication.

The views expressed in this framework are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or Federal Reserve System.