Affordable Rental Housing in Rural Texas

Section 515: An Important Low-Income Rental Housing Program

Texas ranks first in the nation in terms of the number of Section 515 multifamily rural rental properties (646 as of September 2017), and second in the number of Section 515 households (20,330).[10] Section 515 is the largest federal affordable rental housing program for rural communities—a direct-to-developer loan program with approximately 416,000 rental units still in operation nationally as of the writing of this report.

Those eligible to live in a Section 515 property include low- and moderate-income families, the elderly and people with disabilities. Residents never pay more than 30 percent of their income for rent, which ensures they are not cost burdened. Many of these units also include rental assistance through the Section 521 program to reduce the financial burden even more for very-low-income families. The other USDA RD direct loan program, Section 514, provides loans to build, repair or purchase housing for farm laborers. It is a smaller program but still sustains around 16,500 units nationwide.

These rural rental housing sources are dwindling, however. Funding for the programs is at historically low levels, and virtually no new 515 units have been produced across the country since 2011.[11] Complicating matters is the fact that many of these Section 515 and Section 514 properties were financed with loans that originated in the early 1990s and had terms of around 30 years, which means those loans are maturing.

Once the property owner’s loan is paid off and the property exits the Section 515 program, the units may move up to market rates, and residents lose the ability to access rental assistance through the Section 521 program. Potentially exacerbating the housing losses are prepayments, which allow properties to exit the program early. Prepayments had once been such a concern in the 515 program that legislation was enacted that rendered all loans made after Dec. 15, 1989, ineligible for this type of early exit.[12]

Cost pressures will likely increase on low-income rural renters when Section 515 properties mature out of the program. Indeed, current residents of Section 515 units have few other options. A majority of them (63.7 percent) are elderly or living with disabilities and their household income is less than $14,000 a year on average.[13]

However, a Section 515 or Section 514 property owner may elect to stay in the program by taking one of a few different actions, including: re-amortizing the remaining loan balance over a longer term, requesting a debt deferral or transferring the property to a new owner interested in maintaining the property’s status. Owners may be offered incentives like additional rental assistance for tenants.[14] If the owner takes no action, the property will almost certainly exit the program.

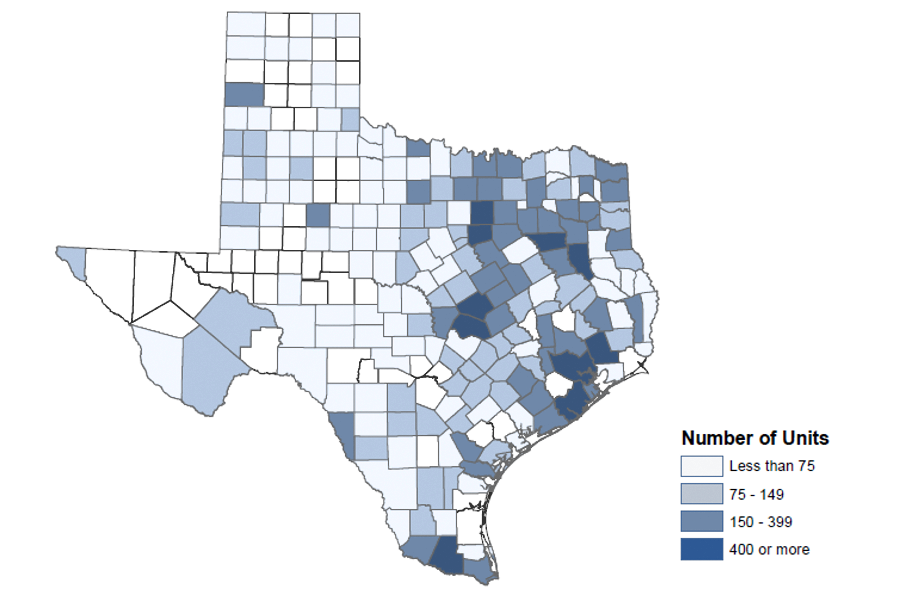

In Texas, Section 515 properties are spread across the state but are most heavily concentrated in East Texas and the Texas–Mexico border area. At an average operating age of 30 years—but as old as 51—some of these properties likely also need renovation and repair.[15] Map 1 shows the concentration of Section 514 and 515 units by county.

Map 1: Concentration of Section 514 and 515 Units in Texas as of 2017

Twenty-five Texas properties are aging out of the 514 and 515 programs from 2018 through 2023. This will result in the loss of 550 units. But by 2030, 6,249 units—over 28 percent of those in operation—will leave the program unless these projects are preserved.

Notes

- Multi-Family Housing Occupancy Statistics Report as of September 2017, U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development, April 6, 2018, www.rd.usda.gov/files/RDUL-MFHannual.pdf.

- “Rural Affordable Rental Housing: Quantifying Need, Reviewing Recent Federal Support, and Assessing the Use of Low Income Housing Tax Credits in Rural Areas,” by Andrew M. Dumont, Finance and Economics Discussion Series no. 2018–077, Federal Reserve Board, 2018, www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2018077pap.pdf.

- “Better Data Controls, Planning, and Additional Options Could Help Preserve Affordable Rental Units,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, May 2018, www.gao.gov/assets/700/691851.pdf.

- “Rental Housing for a 21st Century Rural America: A Platform for Preservation,” Housing Assistance Council, September 2018, www.ruralhome.org/storage/documents/publications/rrreports/HAC_A_PLATFORM_FOR_PRESERVATION.pdf.

- “An Advocate’s Guide to Rural Housing Preservation: Prepayments, Mortgage Maturities, and Foreclosures,” the National Housing Law Project, 2018, www.nhlp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Rural-Preservation-Handbook.pdf.

- Operating age is defined as the initial date of the loan on the project and is used as a proxy for property age.

Authors

- Andrew Dumont

Senior Community Development Analyst, Federal Reserve Board of Governors - Emily Ryder Perlmeter

Community Development Advisor, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas - Julie Gunter

Senior Community Development Advisor, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

The full report can be found at https://www.dallasfed.org/cd/pubs/rural.aspx.

The views expressed in this framework are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or Federal Reserve System.