Affordable Rental Housing in Rural Texas

August 2019

Overview

Rural communities have long faced unique challenges. Some of these include lower median incomes, older housing stock, large aging populations and substandard infrastructure relative to their metropolitan counterparts. The creation of rural-targeted federal programs throughout the decades has been key to mitigating many of these issues. One such program is the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Office of Rural Development (USDA RD) Section 515 Program (see Box 1), historically the largest federal program aimed at subsidizing rental housing in rural communities.

Section 515 addresses the housing needs of very-low-income, elderly and/or disabled residents. At last count, Texas, was home to 646 Section 515 properties, the largest number of any state. However, the level of federal support for this program has been dwindling. No new properties have been built since 2011, with the declining dollars instead directed toward repairing or preserving existing units. And yet over this time, nonmetro[1] Texas has added more renter households (19,000, an increase in share of 1.3 percent) than owner households as the rural homeownership rate has dropped.

At the same time, rents have been rising. Exacerbating this problem is the fact that growing numbers of Section 515 properties are set to exit the program. Exiting the program means a loss of rental subsidies that keep units affordable, which could leave very-low-income, elderly and disabled households with few alternatives.

This paper explores shifts in the housing market and factors that have increased rental-cost burdens across Texas and the country. It examines the loss of Section 515 units and offers strategies for preservation as well as possible alternatives to help mitigate negative outcomes.

Introduction

The financial and housing market crisis of 2008 and 2009 has had a lasting impact. Various factors—including delays in major life events such as household formation and home purchases[2] and tighter mortgage credit conditions[3]—have resulted in the U.S. homeownership rate dipping to a level not seen since the mid-1990s.[4],[5]

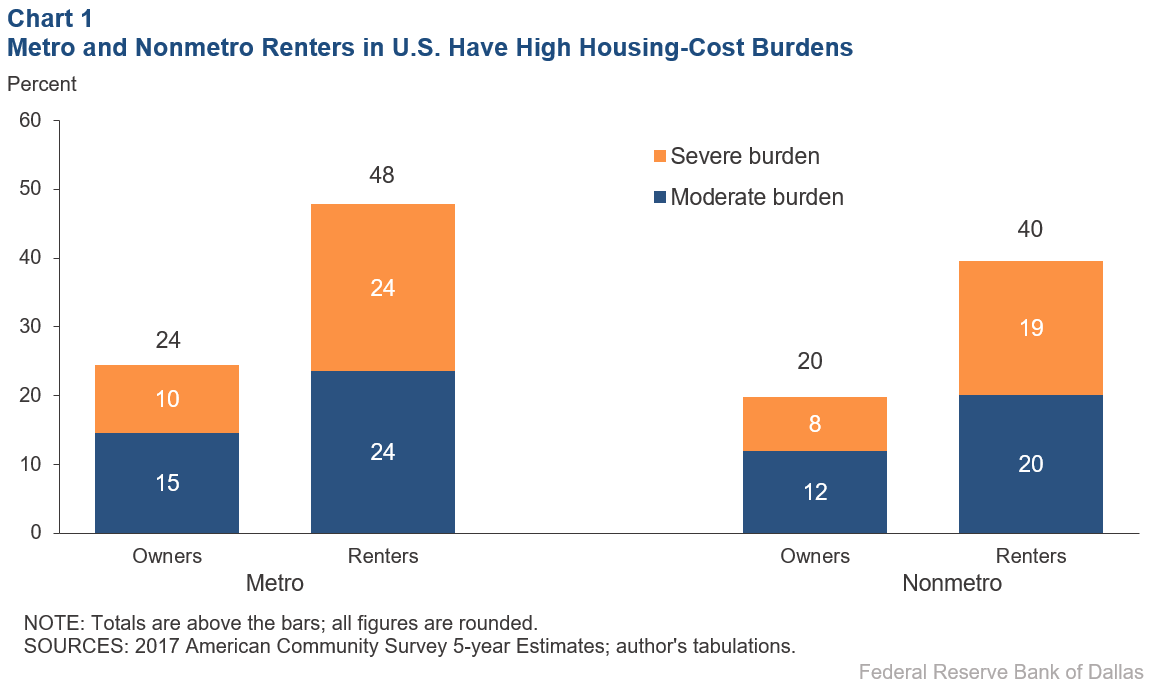

The subsequent increase in demand for rental housing has put significant upward pressure on rental prices—and incomes have not kept pace.[6] This has caused the share of renters in the U.S. who are housing-cost burdened—spending more than 30 percent of their incomes on housing—to surge (Table 1). Renters are about twice as likely to be housing-cost burdened as owners (Chart 1).

Notes

- For purposes of this paper, we use the terms “nonmetro” and “rural” interchangeably, recognizing that some metro areas include substantial areas that the Census Bureau classifies as rural.

- “Headship and Homeownership: What Does the Future Hold?” by Laurie Goodman, Rolf Pendall and Jun Zhu, Urban Institute, June 8, 2015, www.urban.org/research/publication/headship-and-homeownership-what-does-future-hold.

- “The Impact of Tight Credit Standards on 2009–13 Lending,” by Laurie S. Goodman, Jun Zhu and Taz George, Urban Institute, April 2, 2015, www.urban.org/research/publication/impact-tight-credit-standards-2009-13-lending, accessed Sept. 22, 2016.

- Not seasonally adjusted homeownership rate (percent), Current Population Survey/Housing Vacancy Survey, Series H-111, Census Bureau.

- For homeownership, we use the American Community Survey definition, found at “Owner-occupied housing unit rate,” Census Bureau, www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/note/US/HSG445217.

- Median gross rents increased in 67 percent of nonmetro counties and 73 percent of metros between 2010 and 2017, based on author calculations using 2013–2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, and 2008–2010 American Community Survey, 5-Year Estimates.

| Box 1: USDA Rural Development’s Section 515 Program |

|

Federal rural housing programs, based in the Rural Development office of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, were originally conceived in the American Housing Act of 1949. However, it wasn’t until the 1960s that the multifamily direct loan program Section 515 and its related programs, Sections 514, 516 and 521,[1] were funded. Section 515 provides direct loans to individuals, corporations or nonprofit organizations for the construction, improvement or purchase of rural multifamily housing. Although loan terms were up to 50 years in the earliest days of the program, they are currently up to 30 years. Loans have interest rates of 1 percent and amortization periods of up to 50 years. The properties must serve low- and moderate-income families, the elderly and/or people with disabilities.[2] The average income for a tenant in a Section 515 property is $13,600 annually.[3] Sixty-five percent of residents also have Section 521 rental assistance that further reduces their rent obligation. A total of 533,000 units have been produced or preserved under the Section 515 program nationwide since 1963, and the properties currently house more than 630,000 residents. At the height of Section 515’s prominence, in the early 1980s, the program produced about 1,000 properties each year.[4] In recent years, funding for the program has contracted, dropping from $115 million in appropriations in the early 2000s to less than $30 million in fiscal year 2017. No new buildings have been constructed under Section 515 since 2011; funding in recent years has been used entirely for repairing or preserving existing properties. According to the Housing Assistance Council, nearly half of all properties are older than 30 years, and just 12 percent are 20 years or less. Because most have terms of 30 or 50 years, an increasing number of loans are maturing. When a loan matures, a property exits the Section 515 program unless action is taken by the borrower. Once a property leaves, it is no longer subject to Section 515 rules of affordability, and any Section 521 rental assistance leaves with it. Owners are under no obligation to continue to keep units affordable.[5] Nationally, thousands of units have exited the program due to prepayment or loan maturity. An estimated 21,400 units (about 900 properties) will mature out of the program through 2027.[6] The number of units expected to leave the program will accelerate from 2028 through 2040 (16,364 units annually after 2028 and 23,117 in the later years).[7] |

|

Authors

- Andrew Dumont

Senior Community Development Analyst, Federal Reserve Board of Governors - Emily Ryder Perlmeter

Community Development Advisor, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas - Julie Gunter

Senior Community Development Advisor, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

The views expressed in this framework are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or Federal Reserve System.