Horseshift! (With Reference to Gordian Knots)

August 5, 2013 Portland, Oregon

Thank you for that kind introduction, Dana [Bilyeu]. It is somehow comforting to speak to the National Association of State Retirement Administrators. For you, like my colleagues and me at the Federal Reserve, are faced with some very serious challenges. Angst, if not misery, does love company, especially in a beautiful setting such as Portland, Oregon, in August.

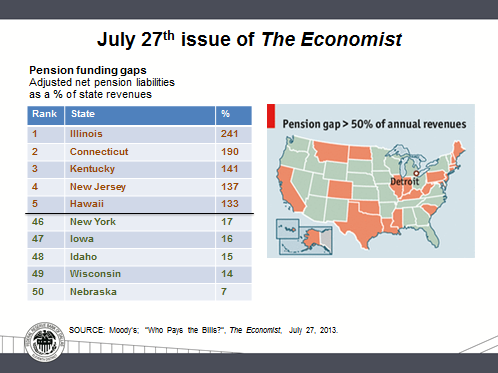

Your anxious predicament—somehow untying the Gordian Knot of underfunded state retirement systems—is summarized for the lay reader in this week’s cover article in the Economist magazine.

I will not attempt to advise you on how to manage the problems written about in that highly respected magazine, as I am sure there will be abundant discussion about funding gaps throughout this conference.

Our predicament at the Federal Reserve is also widely written about. We too have a Gordian Knot to untangle. Like yours, it is anxiety inducing. Let me explain it to you, and in so doing, suggest that we share a common interest in the Fed succeeding in its mission.

A Brief Backgrounder on the Fed

First, a little background on the Federal Reserve. The Fed is the central bank of the United States. We operate under a license given to us by Congress one hundred years ago, a license that has been amended on occasion but has, for the most part, remained intact. The Fed provides the fuel for the nation’s economic engine: We print money, supplying the liquidity needed for job creators to put people to work and expand the wealth and output of the nation. And we are charged with regulating deposit-taking institutions to make sure they are transmitting monetary policy efficiently and operating prudently.

We have to be careful in deploying the fuel we create, for like all fuels, ours is combustible. Employed recklessly or without safeguard, it can lead to an explosion of inflation; if we are too miserly, we risk an implosion of deflation. We can spark a destructive outbreak of speculation or induce excessive risk aversion. We can enhance financial stability or exacerbate systemic instability.

There are 12 Federal Reserve Banks; together we operate the business of the Fed. We make loans to banks. We distribute Federal Reserve notes, more commonly known as “dollars,” to banks. (As an aside, if you look at a dollar bill you can see by the letter printed to the left of George Washington which Federal Reserve District it originally came from: Those with an “L” are the ones ordered from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing by the San Francisco Fed for Oregon and other states that make up the Twelfth Federal Reserve District; those with a “K” are from the Dallas Fed’s Eleventh District, covering principally Texas—these, of course, are the most coveted!) And the 12 Federal Reserve banks house the ground forces of bank examiners who supervise and regulate banks, bank holding companies, and savings and loan companies that lend and provide other services to Main Street.

It might interest you to know that none of the 12 Federal Reserve Bank presidents or their staff is a federal employee, though we work under the watchful eye of the Federal Reserve Board whose governors and staff are. I serve at the pleasure of a nine-person board of directors, chaired by the founder of Southwest Airlines, Herb Kelleher; I do not serve at the pleasure of the president of the United States, nor was I confirmed by the U.S. Senate. The seven members of the Board of Governors, led by Ben Bernanke, are federal employees who are appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. This is the way the Federal Reserve was set up by Congress under President Wilson so as to balance power between the political exigencies of Washington and the financial and economic needs of Main Street.

Making Monetary Policy

In addition to doing the Main Street work of the Federal Reserve System, the presidents of the 12 Fed Banks sit down with the seven Governors of the Fed Board in a body called the Federal Open Market Committee (the FOMC) to decide the nation’s monetary policy. Together, we decide how much fuel to inject into America’s $16 trillion economic engine.

Just as you and your trustees bear the fiduciary duty of properly managing and protecting the value of the pensions under your administration, we at the Fed are charged with the fiduciary duty of managing and protecting the value of our nation’s money supply. And just as your job is conditioned by decisions made by politicians outside of your control, so too is the Fed’s. Let me explain.

By law we are charged by Congress with protecting the purchasing power of money from the ravages of inflation or deflation, a directive we’ve been reasonably successful in satisfying over the past 20 years or so. If we create too much money, we spur inflation; if we create too little, deflation ensues. But Congress has also mandated that we conduct monetary policy so as to achieve full employment, a charge that we have the power to influence but cannot control. Much of the impetus for creating the conditions for full employment depends on how fiscal and regulatory actors incent job creators—where and how much to tax and spend and how businesses are regulated. These decisions are made by politicians the people elect, not by me and my colleagues at the nation’s central bank. As long as inflation is held at bay, the Federal Reserve can put the monetary pedal to the metal, but the vehicle of job creation will not move forward if the fiscal and regulatory authorities have their foot firmly on the brake.

Years of Extraordinary Measures

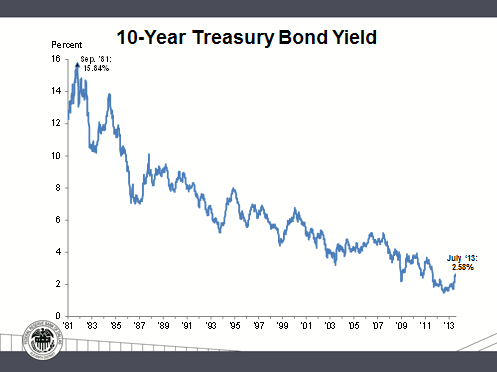

For six of my eight years at the Fed, we have been working to bring the nation’s economy out of recession. The fiscal authorities have for the most part been AWOL during this time, having left the parking brake on during their absence. This has placed the onus on the Bernanke-led Federal Reserve. We have undertaken extraordinary measures, first to get the economy out of the emergency room after the financial system seizure of 2008-09, and more recently, to goose up the private sector to expand payrolls. Toward this end, the Fed cut interest rates to their lowest levels in the nation’s 237-year history by initially cutting the base rate for overnight interbank lending—the “fed funds rate”—to near zero, and then by purchasing massive amounts of U.S. Treasuries and bonds issued or backed by U.S. government-sponsored enterprises (obligations of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac).

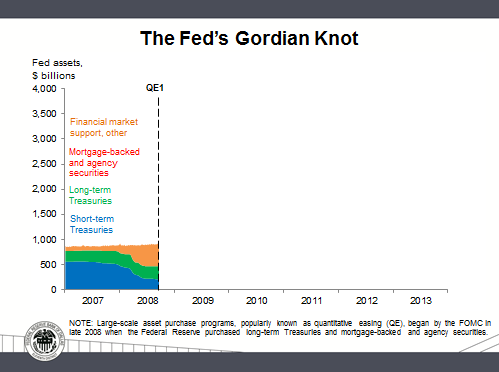

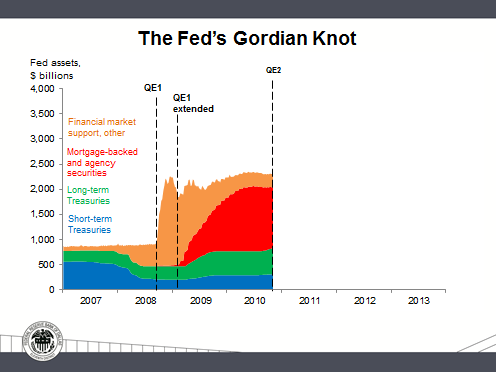

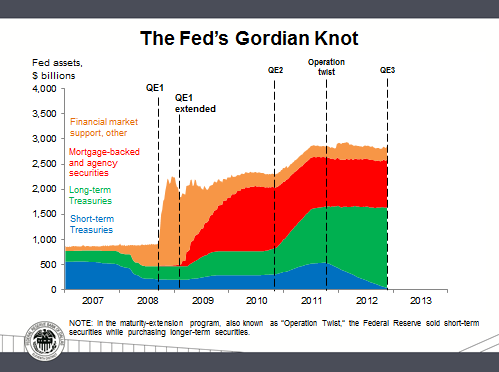

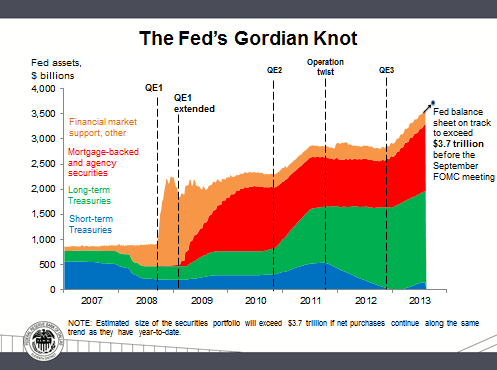

This later program is referred to as quantitative easing, or QE, by the public and as large-scale asset purchases, or LSAPs, internally at the Fed. As a result of LSAPs conducted over three stages of QE, the Fed’s System Open Market Account now holds $2 trillion of Treasury securities and $1.3 trillion of agency and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Since last fall, when we initiated the third stage of QE, we have regularly been purchasing $45 billion a month of Treasuries and $40 billion a month in MBS, meanwhile reinvesting the proceeds from the paydowns of our mortgage-based investments. The result is that our balance sheet has ballooned to more than $3.5 trillion. That’s $3.5 trillion, or $11,300 for every man, woman and child residing in the United States.

The theoretical mechanics behind QE are straightforward: When the Fed buys Treasuries and MBS, it pays for them, putting money into the economy. A key intent of this unprecedented program was to drive down interest rates to such a degree that businesses would achieve a financial comfort level that would induce them to put back to work the millions of Americans that were laid off in the Great Recession. Thus far, only 76 percent of the jobs lost during 2008-09 have been clawed back in the more than three and a half years of modest to moderate payroll gains. This 76 percent figure does not include the 3 million or so jobs that would normally be created to absorb growth in the working-age population.

Muscling the Yield Curve …

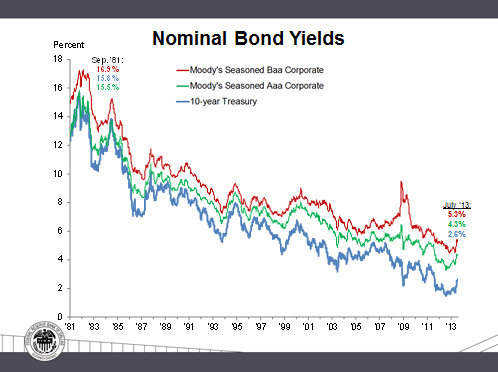

The efficacy of this effort is the subject of significant debate, even internally within the FOMC. Some who question the efficacy, including myself, note that the effect of our purchasing MBS and driving down mortgage rates has certainly assisted a robust recovery in housing, and with it, construction jobs and manufacturing and transportation of materials that go into homes. This was clear from reading the components of the Institute for Supply Management’s manufacturing index released last Thursday, which showed the biggest one-month jump since 1996. Very liberal financing terms for automobiles that we have induced have coincided with an aging of the nation’s auto fleet to regenerate domestic auto sales to the 15.7 million units level. And the Fed’s muscling of the yield curve has brought what has been a 30-year-long bond market rally to a crescendo, as shown in the right-hand bottom corner of these slides.

The historically low interest rates engineered through the Fed’s QE programs have allowed American businesses to recapitalize their balance sheets. Any CEO or CFO worth their salt—running a company that is large, medium or small, whether publicly or privately owned—has by now taken advantage of this to restructure the liability side of their balance sheet. Publicly held companies have benefitted even more as lower rates have driven a raging bull market for stocks. As equity prices break new ground daily, the S&P 500 has soared 153 percent from its March 2009 trough.

And yet job creation has been slow in coming. On this crucial front—the second leg of our dual mandate—we do not seem to have achieved much with the trillions of dollars we have poured into the economy through our three QE programs.

… Is Accompanied by Costs

Counteracting whatever benefits one can trace to the Fed’s unorthodox policies are some obvious costs. First, savers and others who rely on retirement monies invested in short-maturity fixed-income investments, such as bank CDs and Treasury bills, have seen their income evaporate while the rich and the quick, the big money players of Wall Street have become richer still.

Second, the standard return assumptions of 7.5 to 8 percent for retirement pools, as you well know, have been dashed (though I have always felt they were already calculated on an imaginary and politically convenient basis rather than a realistic one).

Third, accompanying the Fed’s growing balance sheet we have seen a dramatic expansion in the monetary base—the sum of reserves and currency. Currently, much of the monetary base has piled up in the form of excess reserves of banks who have not found willing or able borrowers. Other forms of surplus cash are lying fallow on the balance sheets of businesses or being deployed in buying back shares and increasing dividend payouts so as to buttress company stock prices. A basic understanding of demand-pull inflation is “too much money chasing too few goods.” Thus, the excess, currently nondeployed money could prove the kindling of an inflationary conflagration unless the Fed is nimble in managing its effect as it works its way into the economy’s production and consumption of goods and services.

A corollary of reining in this massive monetary stimulus in a timely manner is that financial markets may have become too accustomed to what some have depicted as a Fed “put.” Some have come to expect the Fed to keep the markets levitating indefinitely. This distorts the pricing of financial assets, encourages lazy analysis and can set the groundwork for serious misallocation of capital.

The Challenge of Untying the Monetary Gordian Knot

The challenge now facing the FOMC is that of deciding when to begin dialing back (or as the financial press is fond of reporting: “tapering”) the amount of additional security purchases. In his press conference following our June FOMC meeting, speaking on behalf of the Committee, Chairman Bernanke made clear the parameters for dialing back and eventually ending the QE program. Should the economy continue to improve along the lines then envisioned by Committee, the market could anticipate our slowing the rate of purchases later this year, with an eye toward curtailing new purchases as the unemployment rate broaches 7 percent and prospects for solid job gains remain promising.

Kindly note that this does not mean that the Committee would envision raising the shorter term fed funds rate simultaneously; indeed, the Committee has said it expects this pivotal rate to remain between 0 and ¼ percent at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6.5 percent, intermediate prospects for inflation are reasonable, and longer-term inflationary expectations remain well anchored.

Having stated this quite clearly, and with the unemployment rate having come down to 7.4 percent, I would say that the Committee is now closer to execution mode, pondering the right time to begin reducing its purchases, assuming there is no intervening reversal in economic momentum in coming months.

This is a delicate moment. The Fed has created a monetary Gordian Knot. You can see the developing complexity of that knot in this sequence of slides tracing the change in our portfolio structure with each phase of QE.

Whereas before, our portfolio consisted primarily of instantly tradable short-term Treasury paper, now we hold almost none; our portfolio consists primarily of longer-term Treasuries and MBS. Without delving into the various details and adjustments that could be made (such as considerations of assets readily available for purchase by the Fed), we now hold roughly 20 percent of the stock and continue to buy more than 25 percent of the gross issuance of Treasury notes and bonds. Further, we hold more than 25 percent of MBS outstanding and continue to take down more than 30 percent of gross new MBS issuance. Also, our current rate of MBS purchases far outpaces the net monthly supply of MBS.

The point is: We own a significant slice of these critical markets. This is, indeed, something of a Gordian Knot.

Those of you familiar with the Gordian legend know there were two versions to it: One holds that Alexander the Great simply dispatched with the problem by slicing the intractable knot in half with his sword; the other posits that Alexander pulled the knot out of its pole pin, exposed the two ends of the cord and proceeded to untie it. According to the myth, the oracles then divined that he would go on to conquer the world.

There is no Alexander to simply slice the complex knot that we have created with our rounds of QE. Instead, when the right time comes, we must carefully remove the program's pole pin and gingerly unwind it so as not to prompt market havoc. For starters though, we need to stop building upon the knot. For this reason, I have advocated that we socialize the idea of the inevitability of our dialing back and eventually ending our LSAPs. In June, I argued for the Chairman to signal this possibility at his last press conference and at last week’s meeting suggested that we should gird our loins to make our first move this fall. We shall see if that recommendation obtains with the majority of the Committee.

As administrators of our states’ retirement funds, you have a vested interest in the Fed’s success. After all, the promises made to the good people who have worked for your states can only be kept if financial stability reigns, employment increases and economic growth improves. I believe we are capable of achieving these things, despite suggestions by some that we are locked into a secular trend of subpar growth; I believe that the U.S. is capable of significant economic growth going forward. But only if the nation’s fiscal authorities get their act together and develop policies that complement rather than retard the good that prudent monetary policy can achieve. The fiscal folks need to end the behavior parodied in this little video clip.

Our elected officials’ traditional approach to fiscal matters has been about as cavalier as what you just saw. Given their dissolute behavior, against the background of the problems that beset Europe, the long-standing stagnation of Japan, and the challenges that face China and the emerging market economies that have prospered from supplying the materials needed for Chinese growth, I have often said that “the U.S. is the best-looking horse in the glue factory.” Weak as we have been, we are the best compared to all the rest. I have argued that the principal force holding us back from being the absolute best economy, bar none, has been fiscal management that seems incapable of providing job creators with tax, spending and regulatory incentives to take advantage of the cheap and abundant fuel the Fed has provided so that businesses can put the American people back to work.

I have argued that whatever success we have achieved in clawing our way out of the “Great Recession” has been despite the fiscal and regulatory authorities. Ask any businessman or woman what holds him or her back and they will tell you it’s not monetary policy; it is that they can’t operate in a fog of total uncertainty concerning how they will be taxed or how government spending will impact them or their customers directly. And as to asking their opinion of the impact of regulation on their businesses, don’t even go there, unless you delight in hearing profanities.

Horseshift!

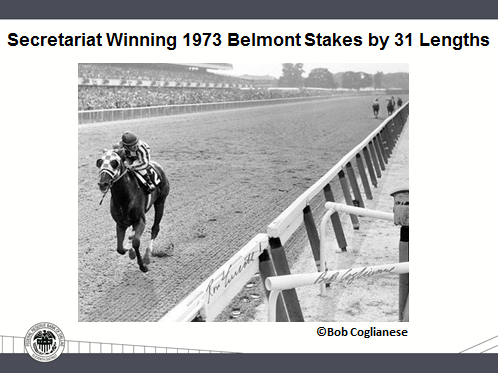

We needn’t be condemned to the glue factory. As I said, American companies publicly held and private—large, medium and small—have taken advantage of the cheap and abundant money made available by the Fed’s hyper-accommodative monetary policy to create lean and muscular balance sheets. In response to the deep recession and the challenges of fiscal and regulatory uncertainty, they have rationalized their cost structures and ramped up productivity, leveraging IT, just-in-time inventory management and new production structures to the max. I believe American businesses today are, far and away, the most efficient operators in the world. We have countless businesses in every sector of goods and service production that are the equivalents of the Secretariats, Man o’ Wars, Citations, Seabiscuits or any great thoroughbred that has ever graced the track. They just need to be let out of the starting gate.

That gate is controlled by Congress, working with the president. If they would just let 'em rip, we would have an economy that would soar. We would experience what, tongue firmly but confidently in cheek, I would call “horseshift”: from being the stuff of an economic glue factory to becoming the wonder-horse that would outpace the rest of the world, putting the American people back to work and renewing the wonder of American prosperity. If you and your fellow citizens from whatever state you hail from insist upon it, it will be done.

Thank you. And now, I would be pleased to avoid answering any questions you might have.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve System.

About the Author

Richard W. Fisher served as president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas from April 2005 until his retirement in March 2015.