Who benefited from the Paycheck Protection Program? Our Texas analysis offers an early look

The $660 billion Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) was launched in April with a goal to keep workers on the payroll at small firms—firms that otherwise would have had difficulty accessing capital in a time of economic crisis. Though many hail the PPP as a historic lifeline for the economy, others have raised concerns that the program reinforces inequities and has led to loan approvals not in alignment with its mission.

Publicly released data on loan numbers, amounts and recipient types and locations have been scant, making analysis of the program’s reach or efficacy unfeasible. However, on July 6, the Small Business Administration (SBA) and the Treasury Department released loan-level data for all approved PPP loans through the end of June, a significant step toward improving the public’s understanding of the program. While limited demographic reporting still makes it difficult to evaluate whether the program has been applied equitably, the data do reveal that the loans were awarded across the demographic map in Texas—including industries most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic response, rural markets and majority-minority ZIP codes.

This article is a follow-up to two previous postings on COVID-19 in the Texas small business community and highlights new analysis on PPP loans and their distribution.

PPP across states

Across the U.S., nearly 4.9 million loans amounting to about $521.5 billion were made from the start of the program through June 30. Firms in Texas received the second-highest aggregate dollar amount at just under $41 billion, behind California at $67 billion. However, large amounts distributed to Texas and California are not surprising given their relative population size and contribution to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

Perhaps a more relevant question is how Texas fared relative to the size of its economy. We looked at how aggregate PPP dollars measured up in each state, both by share of small business payroll and share of state GDP. As referenced in our previous article, Texas falls in the middle of the 50 states in terms of PPP volume as a share of state small business payroll (82 percent).

In Texas, PPP funds represent about 2.2 percent of the state’s GDP. Texas ranks in the bottom fifth among the states in terms of PPP dollars as a share of GDP.

Map 1. PPP Dollars as Share of State GDP

NOTE: Click on state to display loan volume and share of GDP.

SOURCES: Small Business Administration, Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan-level data; Treasury Department; author’s calculations.

In fact, the top three states in terms of GDP (California, Texas and New York) all fall in the bottom quintile of PPP volume as a share of GDP, whereas smaller states like Montana, Vermont, Maine and Idaho all fall into the top quintile (around 3.3 percent).

PPP across industries in Texas

The SBA sought balance between transparency and privacy in its release of individual loan data,[1] which led to the disclosure of two distinct categories of borrower information:

- Loans under $150,000: Business name and address are not included, but precise loan amounts are available.

- Loans $150,000 and above: Business name and exact address are included, but loan amounts are masked in five different range categories.

- $150,000 up to $350,000

- $350,000 up to $1 million

- $1 million up to $2 million

- $2 million up to $5 million

- $5 million to $10 million

Because the precise loan amounts are masked at higher levels, it is not possible to determine exact dollars for geographies smaller than the state and industry level. We can, however, estimate minimum and maximum values for each geography and industry. In the following analysis, we use the range minimums for estimates.

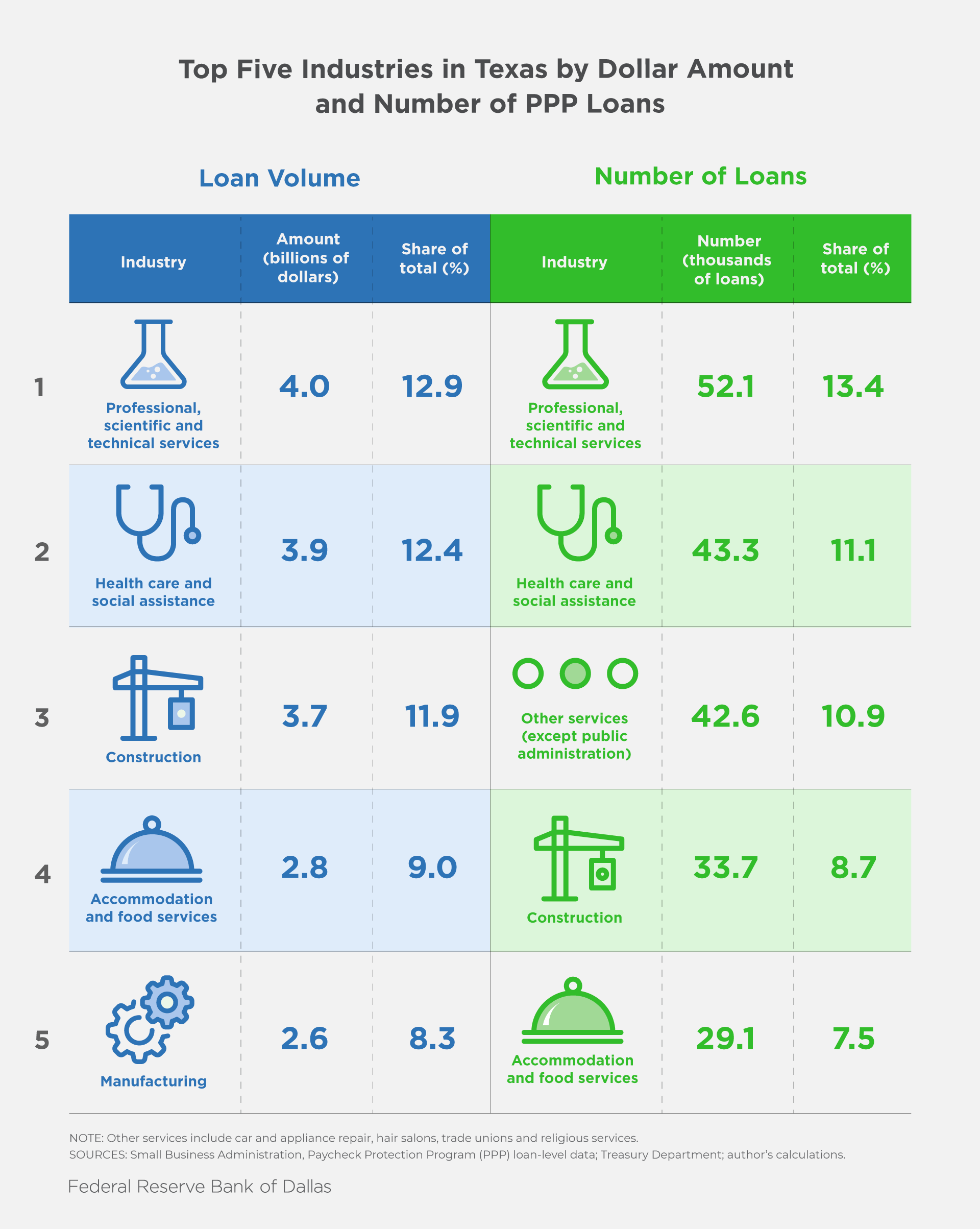

Turning to Texas, we first looked at the distribution of loans by industry. The top industries in terms of loan volume are professional services, health care and construction (Table 1). These three industries were also in the top five by loan count, but “other services” such as hair salons and car repair shops ranked higher than construction and accommodation and food services.

Table 1

Loans to construction firms were more likely to be high-dollar amounts, whereas loans to “other services” firms often fell into smaller ranges, likely reflecting the different average sizes of businesses in those industries.

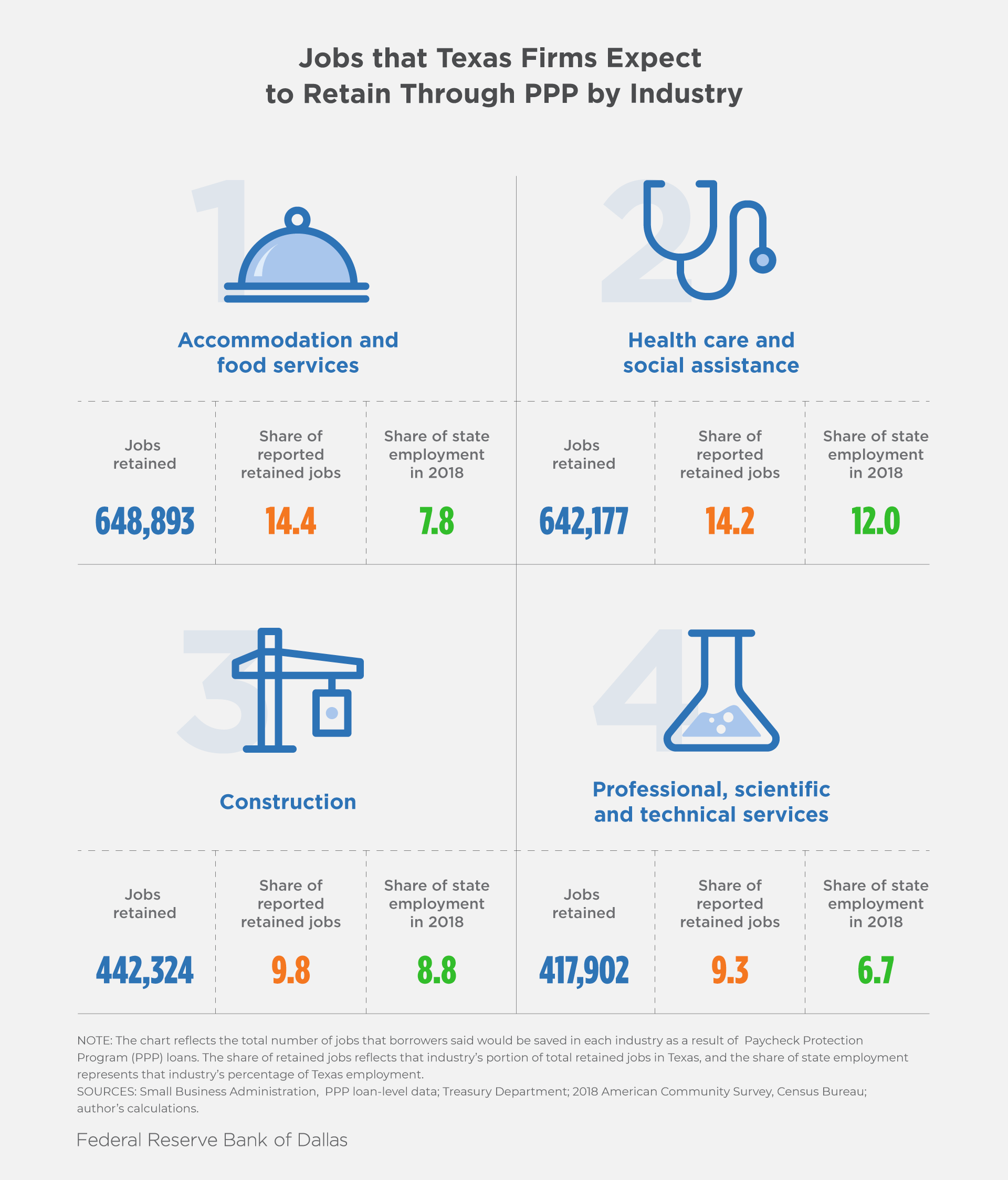

PPP applicants were also asked to report their number of employees to lenders; these self-reports were used to create estimates of the number of jobs retained. According to the data, borrowers in Texas reported more than 4.5 million jobs retained overall. As Table 2 indicates, the industry rankings are similar to those of the loan amounts and loan numbers shown in Table 1. The main exception is the hospitality sector, which accounted for 14.4 percent of the 4.5 million jobs retained despite accounting for only 7.8 percent of total employment in the state.

Table 2

To gauge whether these industries really are among those most heavily affected by the economic impact of COVID-19, we looked at how the reported saved jobs compared with initial unemployment claims filed from March 7 to the end of June. According to the Texas Workforce Commission, the largest share of claims filed during that period was in accommodation and food services (16 percent), followed by retail (12 percent) and health care (10 percent). If we assume that the self-reported numbers of retained jobs are accurate, the PPP seems to have been somewhat successful in targeting those industries most affected.

It’s worth noting, however, that the accuracy of the “jobs retained” data has been widely called into question. According to some analyses, data discrepancies have led to both underreporting of saved job numbers for some firms and overreporting for others. As recipients apply for loan forgiveness, more accurate data are likely to become available.

Geographic spread of loans in Texas

Focusing next on geographic reach, we find that every county except the state’s two smallest (King, pop. 272; and Loving, pop. 169) have at least one PPP borrower. Unsurprisingly, the most highly populated counties have the largest number of PPP borrowers (Map 2). Similar patterns exist for aggregate dollars by county.

Map 2. Total PPP Borrowers by County in Texas

NOTE: Click on county to display loan numbers.

SOURCES: Small Business Administration, Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan-level data; Treasury Department; author’s calculations.

However, as Map 3 indicates, when controlling for the number of workers by county, the pattern of loan volumes is less concentrated in the largest metros. While Harris County has the largest estimated raw-dollar loan volume ($6.3 billion), it ranks 74th of 254 counties for dollars per employee, with just over $3,000. Dallas County has the second-largest total volume ($4.1 billion) but ranks 119th for dollars per worker ($2,557).

Stonewall, a rural county, has the highest PPP dollars per employee at more than $9,000. In fact, eight of the top 10 counties in terms of loan dollars per worker are in rural areas, roughly in line with the overall share of rural counties in Texas.[2] Consistent with this, there turns out to be no statistically significant difference between loan dollars per employee in rural versus urban counties.

Map 3. PPP Loan Amounts by Employment and County

NOTE: Click on county to display loan amounts.

SOURCES: Small Business Administration, Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan-level data; Treasury Department; private employment for all industries, 2019, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, Bureau of Labor Statistics; author’s calculations.

Borrower demographics

Data constraints prevent forming a complete picture of the types of small firms that have received a PPP loan. Although categories like race/ethnicity, veteran status and gender of owner appear on the application form, respondents were not obligated to report those demographics and most decided not to reveal that information.

Table 3 shows the share of borrowers in Texas reporting that they’re veterans, women and people of color, along with the share of nonreporters.

Table 3. Demographic Information Largely Unreported by PPP Borrowers in Texas

| Yes | No | Unreported | |

| Veteran owned | 0.7 | 13.4 | 85.9 |

| Woman owned | 5.7 | 18.0 | 76.3 |

| Minority owned | 4.5 | 6.6 | 88.9 |

| SOURCES: Small Business Administration, Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan-level data; Treasury Department; author’s calculations. | |||

Data also indicate that nonprofits represent 3.1 percent of borrowers in Texas, with nearly 12,000 organizations receiving some PPP funds. Nine nonprofits in the state received loans of at least $5 million. Eight are in either Harris, Dallas or Bexar counties, with one additional location in Webb County (Laredo).

A common concern about the PPP’s process relates to access for small business owners of color, who are less likely to have a bank lending relationship and, therefore, may have had more trouble applying for and being approved for PPP funds. This critique was particularly pronounced in the first round of funding, although some concerns remain. However, only 11 percent of borrowers revealed their race on their application, and there is no way to know whether that 11 percent is representative of the broader population. Therefore, the self-reported applicant data will not shed much light on the pervasiveness of this issue.

What we can do is look at total PPP dollars by ZIP code and compare the result with the share of the white population to better understand the distribution of PPP funds by race and geography.

Initial analysis suggests that, across the state, the average loan size for businesses in majority-minority ZIP codes is higher than for those located in other ZIP codes.[3] Also across the state, majority-minority ZIP codes saw a higher number of loans on average, but this is not surprising: more highly populated ZIP codes also tend to have both higher shares of residents of color and higher shares of PPP loans.

When looking at particular counties, there is no statistical difference in average loan size between majority-minority and other neighborhoods. When considering the urban counties of Dallas, Harris and Tarrant, all three counties initially showed significantly fewer PPP borrowers in majority-minority ZIP codes. Statistically, though, this difference appears to be due to the smaller number of total businesses that are located in those ZIP codes.

Final Thoughts

The Paycheck Protection Program generated nearly 4.9 million loans, providing a total of $521.5 billion to companies across the U.S., from early April through June 30. Within Texas, the nearly $41 billion received has reached almost every county. In contrast to fears that PPP funds would not reach hard-hit industries, sizable shares of loans have gone to the hospitality and health care industries, which have been badly hurt since the beginning of the COVID economic crisis, though the professional services industry received the highest share of loans by number and volume. In terms of jobs, the loan-level data indicate a total of 4.5 million jobs may be retained in Texas, but there is no way to determine how accurate these numbers will turn out to be. PPP borrowers are indeed incentivized to devote a high share of the funds to payroll: They are eligible to have their loans fully forgiven, essentially converted into grants, if criteria such as maintaining or rehiring employees are met and documented. However, there is no current indication of how many borrowers will meet these criteria, nor is it clear how stringently the documentation requirements will be enforced.

Unfortunately, data on borrower demographics are scarce, leaving some of the most burning questions about inclusion unanswerable at the present time. Just 11 percent of borrowers in Texas reported race or ethnicity, and 24 percent reported gender. The SBA stated that across the country, “27 percent of the program’s reach went to low- and moderate-income areas,” an estimate that aligns closely with our Texas analysis. We estimate that the share of loans going to ZIP codes with a poverty rate of at least 20 percent falls between 25 and 31 percent, but we cannot determine what impact the loans will have on those communities.

Data constraints obscure the picture of the program’s potential impact, but the public release of the data does significantly improve our understanding and helps to inform broad estimates. In the loan-level data, addresses are included for loans of at least $150,000. To explore the exact locations of these borrowers in Texas, see Map 4. Zooming in fully to see the point-level data will allow filtering of recipients by loan range as well as reported gender and nonprofit status. Clicking on the point-level data will show the business name and loan range received.

Map 4. Texas Recipients of PPP Loans, $150,000 and Above

SOURCES: Small Business Administration, Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan-level data; Treasury Department.

The PPP officially ended in early August, with over $130 billion left unallocated. While this undersubscription may in part reflect that many firms received the funding they needed, it may also reflect issues that include a lack of access on the part of some firms. In some cases, firms that were in a precarious financial position before the crisis may have been hesitant to take on additional loans, even via a program that promises high rates of forgiveness. In other cases, firms may have been confused about the program rules and requirements given that regulations changed throughout the process. Consistent with these concerns, smaller businesses such as sole proprietorships and independent contractors seem to have been discouraged from applying for PPP even though they were eligible.

As Congress considers future stimulus packages, additional small business funding could still be on the table. It remains to be seen how any future funding would be redesigned and delivered to account for these concerns, but for small business owners, the appetite for more money appears to be high even as a portion of PPP funding goes unclaimed.[4]

Notes

- The data rely on self-reports from borrowers to lenders. This can sometimes create inconsistencies or incomplete information. For instance, the Small Business Administration notes that because demographic information (race and gender) was not mandated, approximately 75 percent of borrowers left those fields blank. There have also been instances of discrepancies in reported numbers of retained jobs.

- “Is Texas Rural or Urban: Growth and Population Are Not Evenly Distributed Across All Texas Counties,” by Tim Brown, County Magazine, Texas Association of Counties, November/December 2019.

- We define majority-minority ZIP codes as those in which the white population share is less than 50 percent.

- “PPP Loans Largely Effective for Small Businesses, Many Still Need More Financial Assistance,” National Federation of Independent Business, July 10, 2020.

About the author