Labor market recovery and wage growth unequal across age groups after pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic had a large and lasting impact on labor force participation in the United States. The number of people working or seeking work declined by more than 8.4 million from February to April 2020, the largest two-month decline on record. As the pandemic has grown less severe, overall labor force participation has edged up. However, it has not reached prepandemic levels, and weak labor supply continues to be cited as impacting economic growth. This article closely examines labor market tightness and breaks down the uneven recovery of labor force participation and wages across age groups, with an eye toward better understanding this important trend.

We find that people ages 20–24 and those over 55 have been less likely to return to the workforce as the pandemic has weakened. Nominal wages have rapidly recovered for younger individuals 16–24 years old but have slowed for older workers, possibly due to the contraction of the college wage premium—the wage boost from earning a college degree—and faster wage growth among lower-income workers.

This article uses Current Population Survey (CPS) data from January 2017 to February 2023 for measures of employment and wages and Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), which is derived from CPS data, for labor force participation from the same time span. We found that:

- The labor force participation rate of prime-age workers (ages 25–54) has recently returned to its prepandemic level.

- Young workers ages 16–19 have been the fastest age group to return to the labor force since the beginning of the pandemic. However, the return to the labor force has especially languished among older workers and has shown no signs of improvement over time.

- While nominal wages have increased across all age groups since 2019, older age groups have faced slower gains. This corresponds with the slower wage gains among higher-income workers.

Sluggish recovery for individuals in their early 20s, even more so for older groups

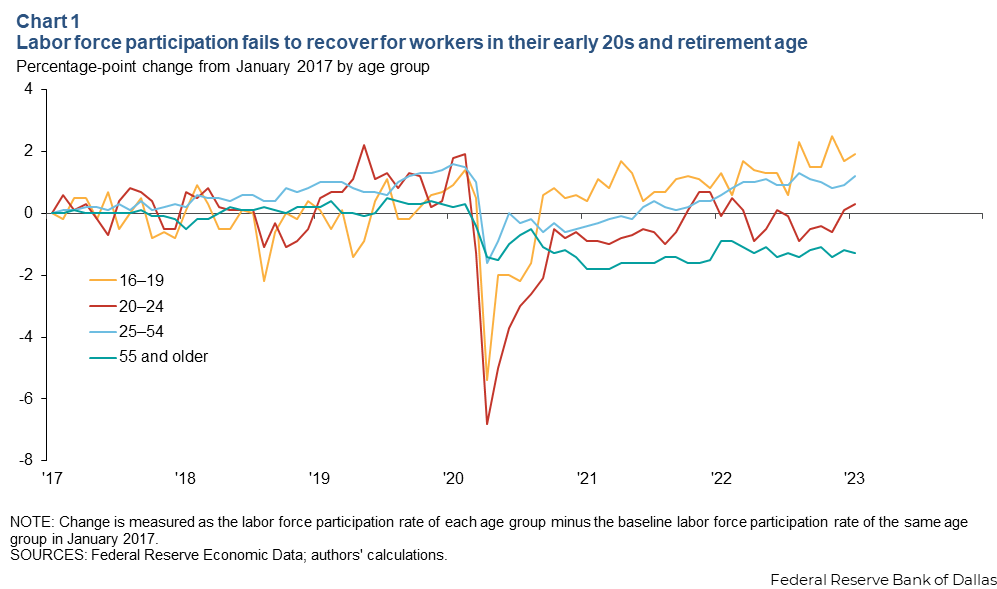

Chart 1 shows the percentage-point change in labor force participation for age groups 16–19, 20–24, 25–54, and 55 and older compared with January 2017.[1]

Labor force participation recovery quickly matched and exceeded prepandemic levels for those ages 16–19 but has been a gradual process for those age 20 and older. This includes prime-age employees.

Young people face a trade-off between school and work. Over the past two years, youths ages 16–19 have become more likely to enter the labor force, increasing their labor force participation more than any other age group since January 2017. Based on our calculations from CPS data, school enrollment reduced by more than 1 percentage point during the first two years of the pandemic. This is notable because individuals who prioritize schooling and earn a high school diploma and college degrees significantly increase their lifetime earning potential. In addition, individuals ages 20–24 have become “disconnected” at higher rates during the pandemic, meaning that they are neither enrolled in college nor participating in the labor force.

Participation among adults ages 25–54 has recently recovered to prepandemic levels. In February 2023, it reached 83.1 percent, which is comparable to the February 2020 level. Meanwhile, labor force participation has failed to recover among those ages 55 and older, hovering around 39 percent since 2021.

Why have older workers stayed out of the labor force? It is possibly because more baby boomers reached their retirement age during the peak of COVID-19. An article from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York claims that most of the loss of older workers can be attributed to baby boomers hitting Social Security eligibility age during COVID-19 years and retiring. Other research suggests this loss may have been abetted by prepandemic-era labor market scarring, which reduced the amount of wages older workers could expect to earn, and a reluctance in some cases for employers to hire older workers.

Nominal wages have increased more slowly with age of earners

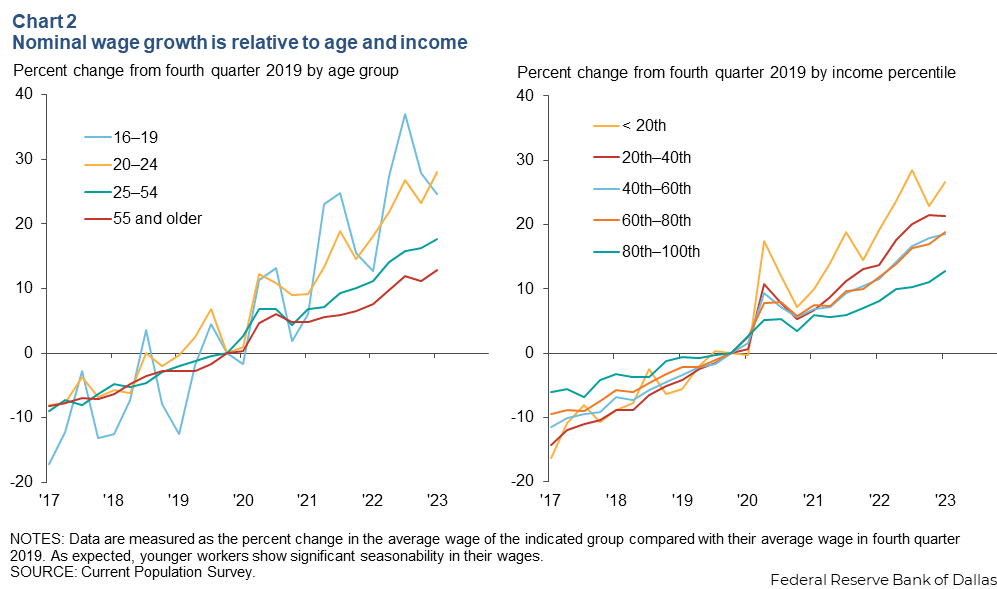

Nominal wages have increased over the past six years, and the pace has picked up since the start of COVID-19. Growth has been more pronounced among younger earners. Nominal wages grew 25 percent for those ages 16–19 and 28 percent for those ages 20–24 from fourth quarter 2019 to first quarter 2023 (our data end in February). In contrast, older age groups have experienced much smaller wage increases—18 percent for those ages 25–54 and only 13 percent for those 55 and older.[2]

The disparity in nominal wage growth is consistent with the parallel findings on income-specific wage growths (Chart 2, methodology identical to a previous article). Younger individuals tend to have lower incomes, so their wage increases constitute a larger percent increase.

Large wage increases for young workers may have incentivized those ages 16–19 to join the labor force, contributing to their high labor force participation rates compared with before the pandemic. Following the same logic, the fact that employees ages 55 and older have not experienced the same nominal wage gains observed by early-career individuals may have contributed to their slow labor force participation recovery, in addition to the exits of baby boomers.

Conclusion

Work patterns have changed substantially since the beginning of the pandemic. Labor force participation recovery and nominal wage growth have generally been faster for younger workers than older ones. The exception is young adults ages 20–24 who saw relatively rapid wage growth but nevertheless experienced an elevated level of disconnection from both school and the labor force.

For workers ages 55 and older, their exit from the labor force could be long lasting. But it is possible that retirees with lower-than-desired savings will return to the workforce. The share of new retirees who have permanently left the labor force is not yet clear.

One potentially lasting implication of the pandemic is that many employees sought more flexible work options, including part-time work.

Part-time work has become more attractive for caregivers, people experiencing burnout and those unable to find full-time jobs. Evidence also suggests that increased flexibility in work options may encourage labor force participation among those who otherwise may not be able to work.

Notes

- We acknowledge that CPS does not update its population count until January each year. This affects the accuracy of the population count for each age group. However, the largest error falls on the older population. Based on a Brookings Institution report , the statistics, with or without weighting, aligned in early 2022.

- Nominal wages are calculated in the same manner as an earlier Dallas Fed article.

About the authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.