Texas winter deep freeze broke refining, petrochemical supply chains

The record-breaking Arctic cold that flowed deep into Texas in mid-February hit the Texas refining and petrochemical sectors as hard as any hurricane and with less warning. Operations did not fully return until early April and sustained lasting damage.

The weather disruption tightened motor fuel supplies, created shortfalls of petrochemicals and slowed Texas exports. The impacts to supply chains have contributed to rising producer price inflation, and the challenges of restocking those supply chains are expected to persist through much of 2021.

Power Producer Struggles

The deep and persistent cold drove up heating demand across a broad swath of the nation. Texas power producers struggled to meet surging demand. Failure to winterize electricity generation infrastructure contributed to power shutdowns.[1] Fearing a collapse of the power grid infrastructure, the agency overseeing it, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, initiated rolling blackouts affecting most Texas residents and businesses.

Among those affected by the double-barreled challenge of cold and loss of electric power were many energy producers and pipeline operators that feed natural gas to electricity generators and industry. The unusual cold even led to instances where the water co-produced with oil and gas in wells froze, reducing the flow of gas available to power generators. Texas natural gas production ultimately fell by 45 percent.

The petrochemical and refining sectors of Texas rely on natural gas and co-produced natural gas liquids—mainly ethane and propane—not only for heat needed during manufacturing, but also for raw materials used in many of their products and processes. The combined effect of electricity blackouts, declines in the supply of raw materials and the intense cold itself forced a rapid shutdown of refinery and chemical plant facilities that required weeks to unwind.

Hurricane-Scale Outages

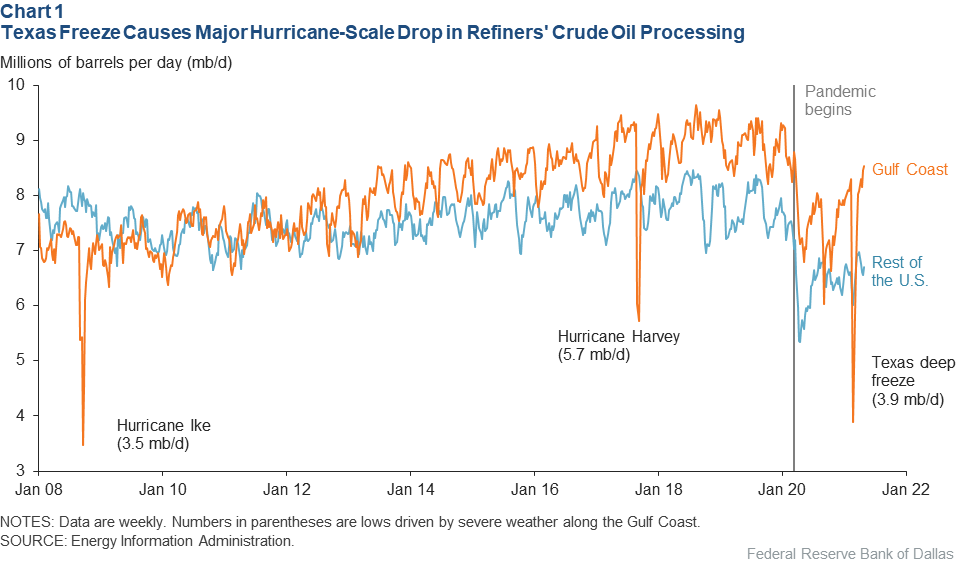

The Energy Information Administration’s report on the Gulf Coast region covers Texas, Louisiana and New Mexico. The region is home to more than half of U.S. operable refining capacity—Texas alone accounts for nearly one-third.

The volume of crude oil processed by these Gulf Coast refiners in February fell to a low of 3.9 million barrels per day (mb/d) on a weekly basis, down from an average of 7.8 mb/d the month before. The roughly 50 percent drop was comparable in magnitude to the weekly impacts of hurricanes Ike (2008) and Harvey (2017). Crude processing recovered to 8.0 mb/d by the end of March 2021 (Chart 1).

Limited mobility during the freeze and a dip in exports helped reduce the immediate effects of the lost supply on U.S. markets. However, the subsequent drop in refiner output amid increasing U.S. consumption following a pandemic lull reduced domestic gasoline and diesel “days of supply”—inventories divided by consumption—to comparatively low five-year average levels. Gasoline fell to 27 days of supply at the end of March, while diesel was at 36 days.

Chemical Output Hit Harder

Refineries typically need as little as 24 hours’ notice to safely shut down—usually in preparation for an oncoming hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico, whose development may have been tracked for over a week. Many chemical facilities need three to five days to stop operations due to the complex interconnections, continuous processes, high temperatures, pressures and the materials involved.

Chemical plants produce a variety of substances from the ingredients for chlorine-based disinfectants and plastic bottles to fertilizers, pesticides and packaging.

Texas is home to roughly three-quarters of basic U.S. chemical production capacity. The largely intermediate goods produced enter supply chains around the country and the world. Most of these goods go through multiple intermediate stages of processing before becoming a final consumer product.

The capital-intensive chemicals manufacturing industry (excluding pharmaceuticals) directly employed 67,100 Texans at the start of 2021, but job multipliers for the industry indicate as many as 4.6 times that number are indirectly supported downstream in supply chains, construction and maintenance, logistics, engineering and other sectors, according to the American Chemistry Council.

The unexpected and long-duration cold, sudden power loss and disruption of natural gas liquids supplies precluded a normal, orderly shutdown. This caused more damage that took longer to identify and repair. For example, in some cases, firms could only identify damaged seals in one part of a plant after completing and testing repairs to other components. Even facilities outside of Texas—or ones not directly affected by the freeze and blackouts—had to cut output in February and March, declaring force majeure in many cases due to shortages of important intermediate petrochemical inputs.

Some producers of polycarbonate resin could not meet production orders. Polycarbonate resin is used to make products such as car bumpers, headlight lenses and the transparent dividers installed over the past year by many businesses to protect customers and employees from exposure to COVID-19.

The auto industry was particularly affected. Toyota and Honda, already confronting COVID-19-related semiconductor shortages and port congestion, faced significant operational challenges. Firms either halted or slowed production at facilities in Mexico, the U.S. and Canada because of a lack of petrochemical components. Honda suspended North American operations for a week in March.[2] Among key shortfalls were polyvinyl chloride (PVC) used for dashboards and other vehicle parts.

As much as 80 percent of U.S. basic organic chemicals capacity was offline after the storm, and up to 60 percent was still offline in mid-March, according to estimates from Wood Mackenzie, an energy industry consultancy. Capacity was largely restored by April.

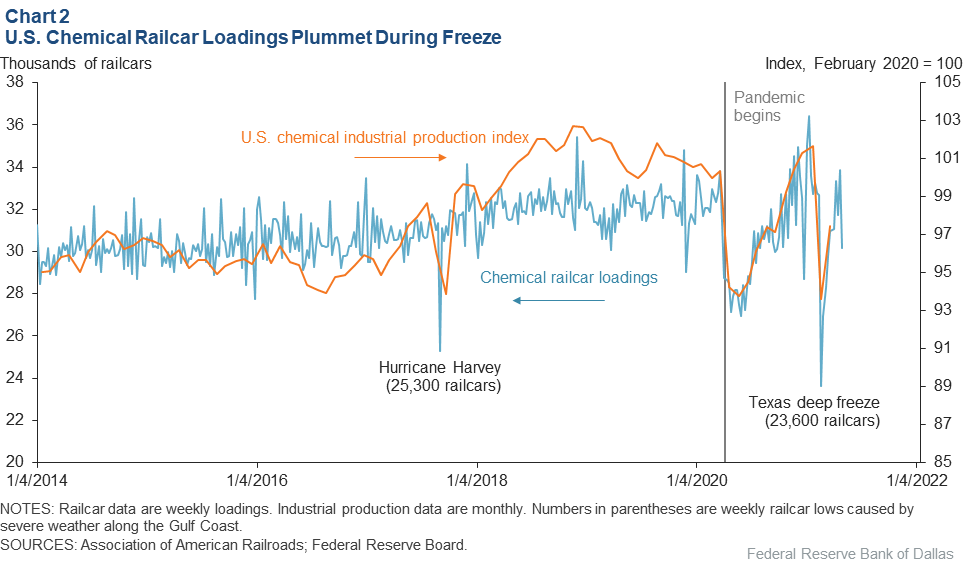

Industrial production of chemicals had surpassed prepandemic levels by the end of 2020 (Chart 2). The index fell 8 percent in February, the largest one-month decline since January 1972. Chemicals is the single-largest industry group in the U.S. industrial production index, with a weight of 13.7 percent.

The average number of chemical railcar loadings—a timelier barometer of chemical plant operations—fell 28 percent during the week ended Feb. 20. That, too, marked the steepest one-week drop since 1988, when the weekly series from the American Association of Railroads began. By mid-April, U.S. chemical railcar loadings had returned to prefreeze—and prepandemic—levels, reflecting the resumption of near-normal operations.

The real (inflation-adjusted) value of Texas chemical, plastic and rubber product exports—which made up nearly 17 percent of Texas exports in the three months before the freeze—fell by more than one-fifth in February 2021, the largest one-month drop since the global commodities bust of 2008. The value of refined product exports (petroleum and coal products) declined over 5 percent.

Petrochemical Price Surge

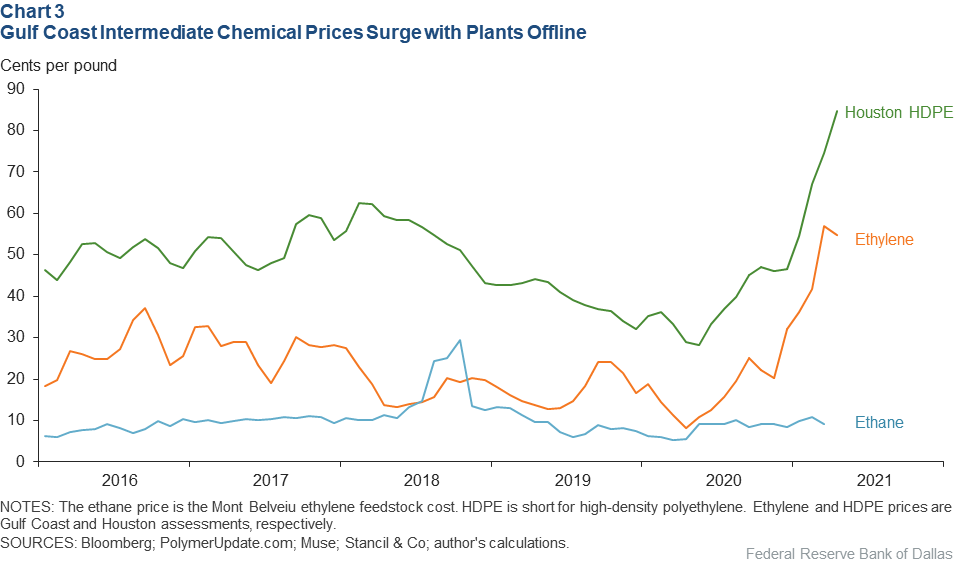

Gulf Coast chemical prices exceeded prepandemic levels at the end of 2020 due to rebounding product demand and rising crude oil prices (Chart 3). Moreover, producers, wary of a growing second wave of coronavirus globally, had slowly rebuilt inventories of intermediate product that were depleted following hurricanes Laura (August 2020) and Beta (September 2020). This kept industry inventories seasonally tight at the start of 2021.

The price of ethane—a key raw material for petrochemicals—has been relatively stable since summer 2020.

Intermediate product prices, however, have skyrocketed. The Gulf Coast price of ethylene surged 78 percent from December 2020 to March 2021. The increase pushed high-density polyethylene prices up to 75 cents per pound in March, a 61 percent jump. Ethylene feeds into myriad consumer products such as Styrofoam cups, plastic bottles, packaging and auto parts.

Rising Producer Prices

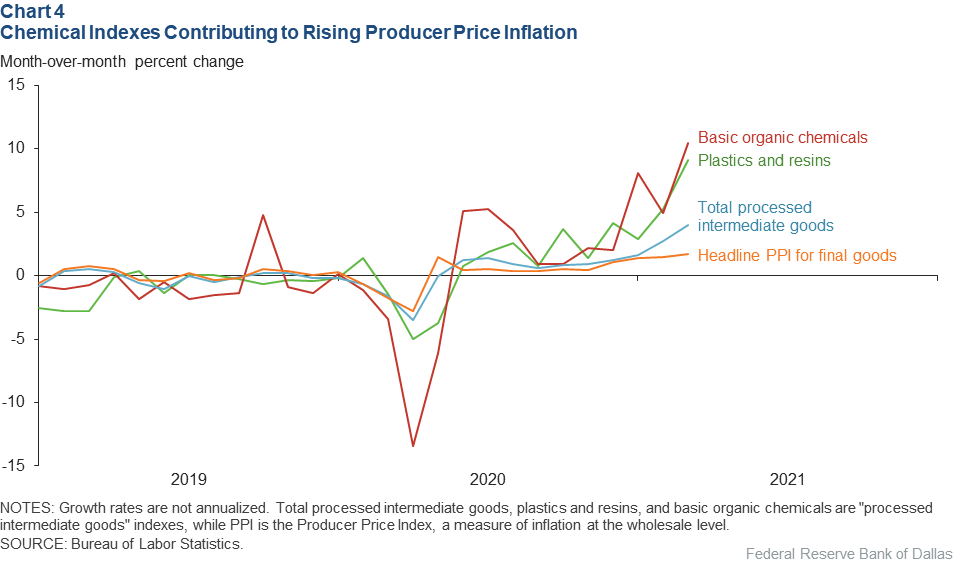

The increased chemical prices and related disruptions to supply chains added upward pressure to U.S. producer price indexes (PPIs).

The basic organic chemicals index (which tracks the prices of processed intermediate goods and includes ethylene) rose 10.4 percent from February to March 2021 (Chart 4).

Plastics and resins (which include polyethylene) increased 9.1 percent in March. Both were the fastest monthly rates of increase on record for these series, which began in 2011. The broader chemicals and allied products PPI logged its highest monthly growth since August 1974.

Lingering Effects in 2021

Even with chemical production back to prepandemic levels, supply chains aren’t yet fully restored.

Consumer demand during the pandemic proved resilient as households ordered more to-go boxes from restaurants, demanded more personal protective equipment and required more packaging for online shopping orders. This helped offset lower demand for products such as motor oil additives and tire rubber, where consumption fell as people stayed home.

With little spare production capacity across the chemical sector, most new production will go to meeting new orders—likely keeping inventories thin throughout supply chains. The lack of wiggle room should support recent high prices or even lead to still-higher prices should demand increase further.

The pandemic has produced lingering logistical challenges in shipping. International shipping costs have skyrocketed in spot and contract markets, particularly for trans-Pacific crossings. This is in part because the number of vessels in service has not fully recovered from 2020 lows, when lockdowns initially curtailed demand.

Shipping containers were left misallocated as the logistics of pandemic lockdowns limited the backhaul of empty containers used for moving bags of resins and other substances. Recurring coronavirus lockdowns affecting ports and businesses around the world may continue constraining shipping and container capacity, further challenging the restocking of chemical supply chains and broadly contributing to higher import costs.

Reaching Market Balance

Refiners and petrochemical producers’ optimism grew as the economy strengthened in second quarter 2021 and COVID-19 vaccines became more plentiful. Industry officials say they remain wary about additional lockdowns arising from recurring illness in large demand centers such as India.

Forecasts for global crude and natural gas liquids consumption from the International Energy Agency were revised upward, and chemical industry contributions to the U.S. Purchasing Managers Index grew strongly as outlooks improved.[3]

Restocking inventories and fortifying supply chains will be challenging, although petrochemical industry executives believe that full normalization could occur by year-end 2021.[4] More production from new capacity coming online—$5.7 billion worth in Texas, according to the American Chemistry Council—could help some product markets if it is brought into operation early enough in 2021. However, higher-than-normal production rates through the fall and improved global shipping and logistics environments will likely be needed.

The 2021 hurricane season in the Gulf of Mexico provides another variable. The ability to gain control over COVID-19 is also an unknown. Whatever occurs, the near-term impact of the Texas deep freeze on the chemical industry is expected to reverberate through supply chains across industries for the rest of the year. When these transitory factors fade, upward industry price pressures are expected to dissipate.

Notes

- “Cost of Texas’ 2021 Deep Freeze Justifies Weatherization,” by Garret Golding, Anil Kumar and Karel Mertens, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Dallas Fed Economics, April 15, 2021.

- “Toyota Partially Halts North American Auto Production on Plastics Shortage," by Adam Yanelli, Independent Commodity Intelligence Services, March 18, 2021.

- “March 2021 Manufacturing ISM Report on Business," Institute for Supply Management (ISM), April 2021; and “ISM-Houston Business Report on Business,” by Ross S. Harvison, ISM, March 2021.

- Eleventh District Beige Book, April 14, 2021; “Texas Petrochemical Production Is Still Thawing,” by Alexander H. Tullow, Chemical and Engineering News, March 21, 2021; and “U.S. PPG Expects Most Product Inflation to Subside in H2 2021, After Q1 Rise,” by Deniz Koray, Independent Commodity Intelligence Services, March 16, 2021.

About the Authors

Jesse Thompson

Thompson is a senior business economist in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2021/swe2102.