Panel 1: Rules of Origin: U.S. Content of Imports, Supply Chains and Trade Diversion

Pragmatism May Ultimately Guide Mexico’s USMCA Energy Policy

I’ll try to offer an alternative perspective to what you may have been reading and watching on news outlets regarding what’s happening in Mexico’s energy sector. This perspective is based on over 30 years of a close personal relationship that my boss, Ambassador Jim Jones (Monarch Global Strategies chairman), has had. He was ambassador in Mexico when NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement) passed, and he developed a great friendship with (Mexican President Andrés Manuel) López Obrador and key sub-officers who are back in the administration.

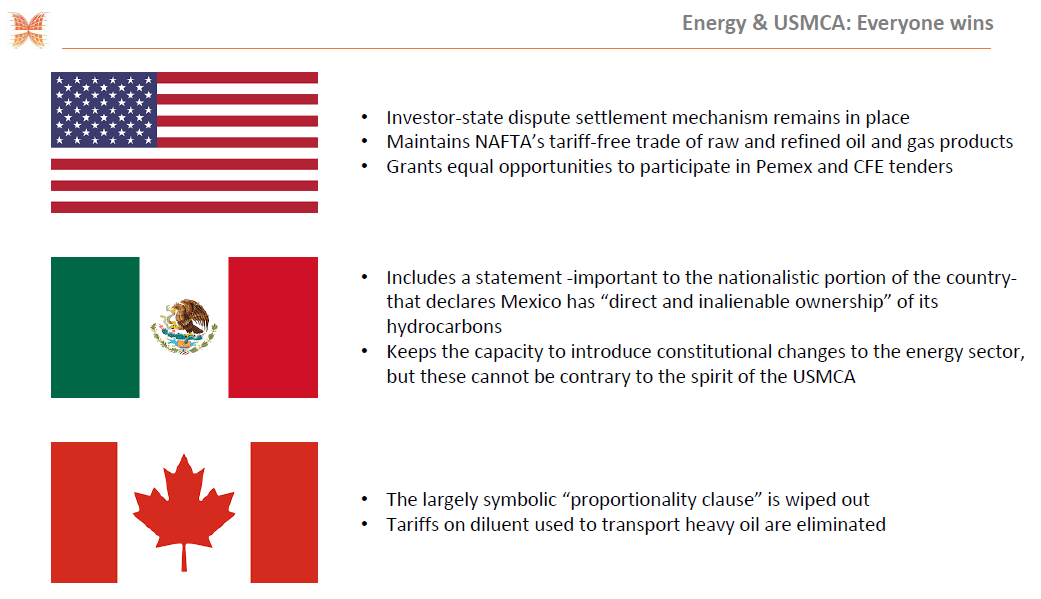

Let me start by saying that all parties were able to claim a victory from the USMCA (the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement) when it comes to energy (Chart 1). For the United States, the oil and gas industry can celebrate what did not change. Mexico and Canada were able to introduce provisions important to their interests. Despite initial threats to remove it, the investors’ state-dispute settlement mechanism between the United States and Mexico was preserved for a handful of industries, including oil and gas and (electrical) power. As a result, investments are provided with much needed certainty over their ventures in Mexico.

Chart 1

The agreement also maintains NAFTA’s allowance for tariff-free trade of raw and refined oil and gas products between the United States and Mexico. And it granted equal opportunities to participate in Pemex and CFE (Comisión Federal de Electricidad, the Federal Electricity Commission) tenders, which is very important given President López Obrador’s ambitious plans for the sector. For Mexico, the USMCA—as Enrique (Marroquin of Hunt Mexico) has mentioned—included a statement that was very important for López Obrador that declared that Mexico has direct ownership of its hydrocarbons. Meanwhile, Canada was able to wipe out the largely symbolic proportionality clause and to eliminate truck tariffs on diluents used to transport heavy oil. The USMCA should support continued integration of energy interests within North America.

The bigger determinant of future investments, I think, rests within the Mexican administration. Despite (its) initially slowing down the energy reforms, I believe that foreign expertise and investments will be needed to achieve AMLO’s (President López Obrador’s) social and economic goals. And the USMCA energy provisions should give investors the confidence to make this happen. It may be hard for outsiders to understand that a very significant portion of Mexicans view those natural resources as a source of national pride, almost as a divine right. AMLO’s opposition to the energy reform played a major role in getting him elected. However, AMLO is a very pragmatic politician, and he understands that private investment is needed in order to achieve his goal of 6 percent growth by the end of his administration. One other key issue—and it has been discussed previously—is that he wants to bridge the gap between the north of Mexico and the impoverished southeastern part of the country.

AMLO’s ambivalence on energy reform is revealed in his choices for the cabinet. The secretary of energy, the director of Pemex and the director of CFE are all nationalists who strongly oppose the energy reform. The office of the president (which is in charge of the strategic relationship with international investors), the all-important finance ministry and the Mexican ambassador to the U.S. are all big proponents of open markets and an open energy arena. There can be little doubt that the energy team initially shaped the strategies and rhetoric for the energy sector. Oil and gas routes and electricity auctions were canceled. Regulatory agencies like Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH) (National Hydrocarbons Commission) and Comisión Reguladora de Energía (CRE) (Energy Regulatory Commission) came under attack right after AMLO’s rise to power. But as the administration came to terms with the realities of governing, these strategies have been evolving at a modest pace.

The pragmatists in AMLO’s team know that the energy sector is key for the successful implementation of their social policy. As proof of this evolution, the CNH has resumed the approval of oil development plans for privately held oil fields. And Secretary of Energy (Rocío) Nahle just announced this past week that auctions may come back shortly with some changes in the way that they will be implemented—but it’s a welcome change. Exploration and production service contracts are under review to make them more appealing for companies. They are being linked to public–private partnership agreements.

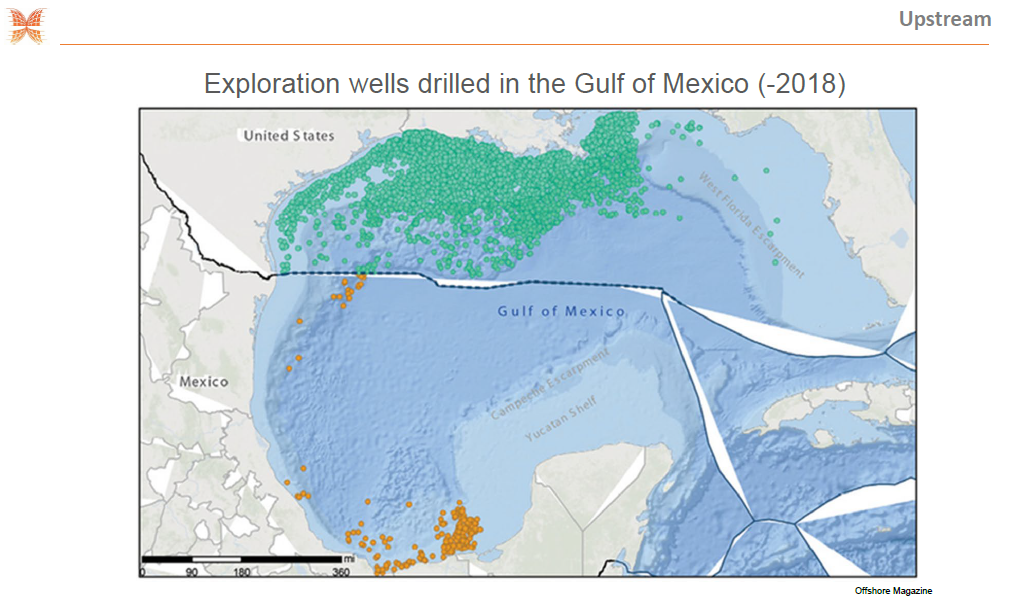

Chart 2 shows how much needs to be done on the Mexican side of the Gulf. There is a big opportunity for business. Since peaking at 3.4 million barrels per day in 2004, Mexico’s oil production has been falling. We estimated that in order to return to 2004 levels of production, Mexico will require anywhere from $30 billion to $40 billion of investment per year. Even to reach AMLO’s own goal of increasing production to 2.6 million barrels per day, he’ll need at least $25 billion in investment. I mean, as Enrique (Marroquin) was saying in the case of CFE, Pemex does not have that kind of money—and I don’t think they will ever have it—especially since the new refinery is being given a great deal of importance, and a big part of the budget for Pemex is being allocated to construction of that refinery.

Chart 2

Pemex is the most indebted oil company in the world, and so money needs to come from a different alternative, and that alternative is private investors. The administration is beginning to understand the importance of continuing with the energy auctions, but it will still take them some time. The fact that service contracts are being sold as public or private partnerships on Pemex’s 20 priority fields is a good sign. While these contracts might not be interesting enough for operators and oil giants given the lack of exploration upside—and are too risky for Mexican services companies—we’re witnessing a nascent understanding of what the industry needs to be attractive. This understanding was not there when the president was elected. They are finally catching up with the reality of governing.

This new understanding also provides an opportunity to review and enhance the auction processes and take away what didn’t work. Companies of all sizes operating on the U.S. side of the Gulf of Mexico will have a clear advantage given that they have the most experience and the technology they have developed over decades of exploration and production in shared geological columns.

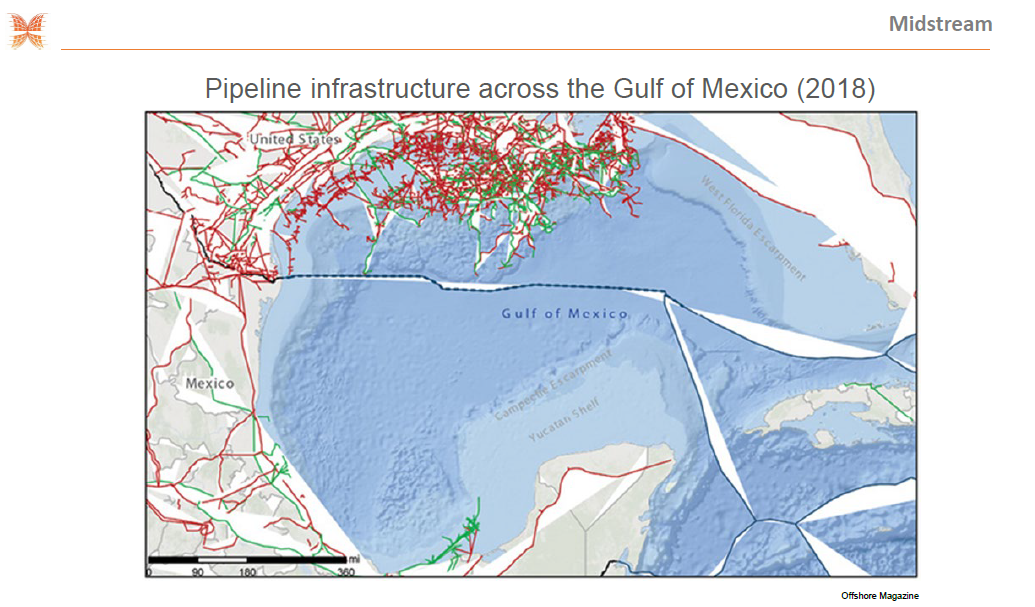

As you will see in Chart 3, the infrastructure is already in place, and that should set American and Canadian companies apart from competition from other parts of the world. So, there is a pipeline infrastructure across the Gulf of Mexico. It shouldn’t be hard to begin connecting that infrastructure to the Mexican side of the Gulf once investments get back on track.

Chart 3

I won’t describe much about midstream, but I think that one example of the evolution that I am talking about in AMLO’s understanding of having partners in the energy arena is the recent pipeline renegotiation issue. To provide a quick recap, CFE Director (Manuel) Bartlett wanted to get rid of some pipeline development projects. Bartlett threatened to take the pipeline developers to international arbitration. However, President López Obrador immediately took matters into his own hands, appointing a representative from his office to lead talks. Although it was not made public, he made Bartlett take a side door and he did not participate in those talks. Of course, when the issue was resolved, Bartlett received the applause.

What I mean is that in the end, all parties were able to claim victory, and I think that companies were very happy with renegotiation. At least that’s what my friends tell me; they celebrated. So, this self-inflicted wound was a key learning experience for the Mexican government, which brought uncertainty into an already distrustful investment ecosystem and unnecessarily endangered the support for the USMCA in the U.S. and Canada.

In the downstream sector—I won’t talk much about it—but the refinery in Dos Bocas is perhaps AMLO’s most controversial flagship project. However, there will be opportunities for investments in modernizing Mexico’s existing refineries. One of them was built 70 years ago, and they really haven’t kept up with new technologies because of a lack of funds. The administration is allocating a ridiculously small budget to revamp these refineries—about 30 times less than what conservative estimates suggest is needed. I mean, we’re talking a need of about $15 billion to $20 billion. And this year, they were allocated $250 million for modernization.

So, we will keep importing fuel for the time being. But another opportunity lies in the petrochemical industry, which is practically nonexistent in Mexico.

We think that if you want to do business in Mexico, you should first understand what the goals of AMLO’s administration are and try to align your investment projects with his goals. In our meetings with him since his election, we have been very successful by putting things in perspective in a way that resonates with him. How does your project offer development to the people? Does it create technology transfer and/or knowledge transfer? All those things are important to him.

He’s not a numbers guy, so if you begin talking about dollars and cents and the bottom line, you will lose him—you immediately lose him. When you bring up benefits for a community, for a region and how this project can help him achieve his goals, you get his attention back. Over the past 30 years, López Obrador has built a political persona he has to keep up with, and his public discourse is often inflammatory. Behind closed doors in his office, he allows his pragmatic side to surface.