Panel 5: Migration, Workforce and the Integration of Labor Markets

U.S. Wage Growth Provides Greatest ‘Pull’ for Mexican Migration Decision

A lot of what I’m going to talk about draws on my research with Pia Orrenius (of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas). We wrote a paper for the Center for Global Development that looked at unauthorized inflows of Mexican workers for the past 20 years or so.

I think you all agree, certainly living in Texas, that Mexican worker migration matters. It matters a lot to us in Florida as well. But on a grand scale, it’s important to the U.S. economy that about one-sixth of our workers are foreign born and Mexicans alone are about 5 percent of workers in the United States. They’re an incredibly important source of workers. They’re also our neighbors. They’re students. They’re colleagues. They are very important as consumers, workers and friends.

They’re also important to the Mexican economy. When the Mexican economy experiences a downturn like the Tequila Crisis, for example, the U.S. has historically served as an outlet for those workers to leave. That helps stabilize the Mexican economy as well as potentially benefiting the U.S. economy. In the same way, 50 years ago when Mexican women were having six kids instead of two, the United States once again served as an outlet for that excess labor force.

Another important thing to Mexico that perhaps we haven’t talked about as much over the last day and a half is remittances that Mexican workers in the United States send back to Mexico, on the order of $25 billion annually. And that really helps stabilize the Mexican economy. It’s an incredibly important source of funds to a lot of communities and families. And perhaps those funds going there affect the number of people who are coming to the United States as well.

Looking ahead, changes in demographics in the U.S. and in Mexico make these flows and what’s going to happen to them very important. I think perhaps the most jaw-dropping thing that Jeff Passel (of the Pew Research Center) just showed us was what the future of the U.S. labor force would look like without immigrants. It is hard to understate the importance of immigrants to the future of the U.S. workforce. Historically, many of those immigrants have been from Mexico, but that has been changing.

As economists, the way that we think about immigration is typically push versus pull factors (Chart 1). What’s pushing them to leave their country, and then what’s pulling them into another country as well. Thinking about the push factors from Mexico, one important set of factors is economics. What’s happening with Mexican wages? When they’re going up, we would expect fewer people to be pushed out.

Chart 1

When jobs are growing in Mexico, when you have rising employment particularly in the formal sector, you would also expect a weaker push factor. Trade with the United States and Canada, the creation of NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) and then what’s happened after NAFTA could, of course, be an important factor in whether or not Mexican workers are feeling pushed out into the United States.

Although it pains me as an economist to say, economics is not all that matters. Demographics matter as well. In particular, this is where the age structure and that drop in the number of children born to the average woman in Mexico matters a whole lot. If you’re part of a baby boom, when you enter the labor market, you’re facing a lot of competition. There’s a big increase in labor supply at the same time as you’re joining the workforce. For a lot of people in Mexico, that baby boom, when it was happening 40 to 50 years ago, eventually acted as a push factor. That has, of course, diminished a lot as birthrates have fallen.

Switching over to the United States—thinking about Texas, California and the whole rest of the country—we act as a magnet that is potentially strong, potentially weak, in attracting workers from Mexico and elsewhere. Again, here economics is important. What we would expect is, as U.S. wages are rising, either overall or for the type of people who might enter, we would have a stronger magnet when U.S. jobs are more plentiful and the unemployment rate is low. We’d expect again a stronger magnet. When we think about Mexico, one important economic factor is what’s happening with U.S. construction activity.

When you think back to the early 2000s, when we had a housing boom in the United States, it was potentially a very strong magnet attracting lots of workers. Then, we have the housing bust starting in about 2006, and suddenly that magnet just really disappeared. As we’ve been going back through another housing boom—weaker, but still a boom in the last few years—potentially that magnetic pull is back.

Again, economics isn’t all that matters. There’s also U.S. demographics—what’s happening with the aging of the U.S. population, how many potentially competing workers there might be for Mexicans who might consider coming to the U.S.

Finally, one potential block on that pull factor is border enforcement, particularly during the period that Pia Orrenius and I looked at—the 1990s and early 2000s. Whereas now, we would also be very concerned about rethinking interior enforcement as well.

In this paper, we estimated the inflow of unauthorized Mexican workers. We took a whole bunch of U.S. government data that’s publicly available, and we tried to count the number of people in the U.S. labor force who were born in Mexico and who appeared to have not been in the country in the last year (Chart 2).

Chart 2

We think about this inflow as new entrants; that is, the gross inflow of Mexican workers. What we were particularly interested in in this paper was how much of that gross inflow of Mexican-born workers appeared to be unauthorized. Here we adjust for an undercount. The government does not ask people if they are unauthorized because who would answer that accurately? People are kind of reluctant to cooperate with government surveys. They’re long. They’re intrusive, and if you’re an unauthorized immigrant, you’re particularly reluctant to cooperate with these surveys. So, the surveys undercount the number of immigrants in the U.S., in particular the number of unauthorized immigrants.

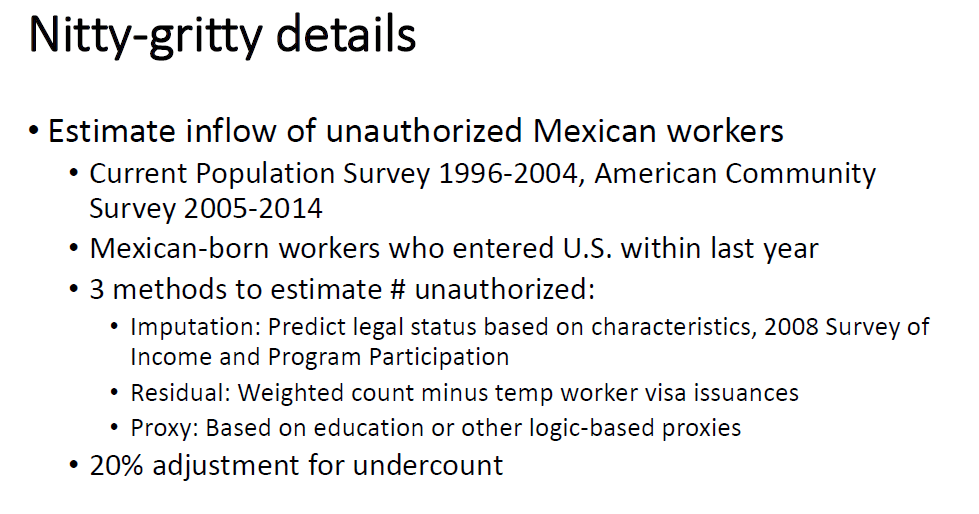

We are interested in the gross inflow—the number of workers newly coming over the border—and also in the stock. At any point in time, how many unauthorized Mexican workers appear to be in the United States? This is what one estimate of our numbers looked like (blue line in Chart 3). We think it’s a pretty good number because it follows closely estimates from the Pew Research Center (red line) and estimates coming from the Department of Homeland Security (green line).

Chart 3

What you tend to see here is that the stock of unauthorized Mexican workers or the immigrant population as a whole, as Jeff Passel was saying, was going up through the Great Recession, until about 2007, and then it started to fall.

What does the widening gap (between the blue and red lines) mean? If we’re right in our estimates, it is the fraction of unauthorized Mexicans who are (not working) here in the United States. You still have a decline in the unauthorized Mexican immigrant population in the U.S., but you have an even bigger drop in the number of those who are working. Why is that occurring? Why are fewer unauthorized Mexican immigrants working? Probably because we’ve made it harder for them to work through interior enforcement, through E-Verify (the federal worker eligibility verification program), through Secure Communities, through the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Program 287g (cooperation between federal, state and local law enforcement), through a lot of these programs that are discouraging work within a population that has no safety net to fall back upon.

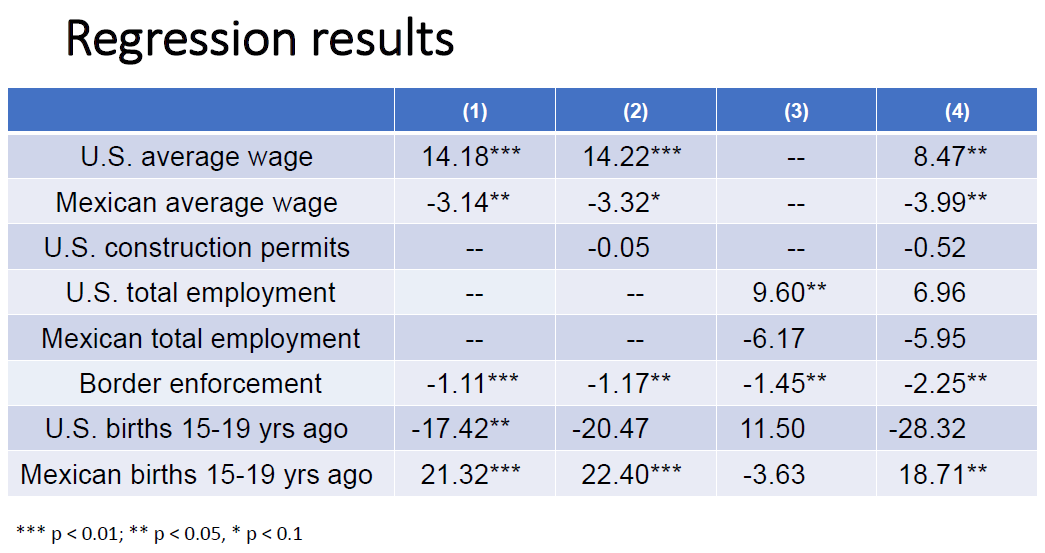

What we’re interested in is, of course, the why. What was going on? What were the drivers of this inflow with regard to push versus pull factors? We ran these regressions, and we have a whole bunch of regression results. What are the takeaways from all of these numbers?

One is that U.S. wages are a very important magnet. If U.S. wages are growing 1 percent faster, inflows of unauthorized immigrants from Mexico are about 8–14 percent higher (Chart 4). The better the U.S. economy, the more people try to come. Mexican wages act as a push factor when they fall (more people leave); with a 1 percent drop, about 3 percent more leave. But they (Mexican wages) don’t matter as much as U.S. wages do. The pull factor is more important than the push factor. Border enforcement matters. Construction activity does not matter a whole lot. But the size of those birth cohorts matters as well.

Chart 4

What might happen in the future? What might we expect? Well, if things continue like they’ve been for about the last five years, these gross flows will be about 100,000 per year. Is that high or low? Well, that’s a very normative question, but what is important is that this is very low in a historical context. When we go back to before the Great Recession, those numbers were about 220,000, gross, coming over per year, and more of them were staying. So, we predict much lower flows. But if U.S. economic growth were to strengthen, those flows would increase considerably. If the Mexican economy were to weaken, those flows would also strengthen, but not by as much. Remember, the pull is bigger than the push, and of course, you know there are lots of caveats—they’re hard to predict.

So, what does this mean for policy? This is all talking about unauthorized immigrants. I think most of us would agree that we would prefer that immigrants come to the United States legally, but the problem is U.S. legal immigration programs are a mess, both on the permanent side and on the temporary side. And it is so much easier for an employer to hire someone who’s already taken the risk of crossing and is here illegally than to try to bring in a worker legally. The paperwork and the wait time for a visa and the uncertainty associated with trying to do that is tremendous.

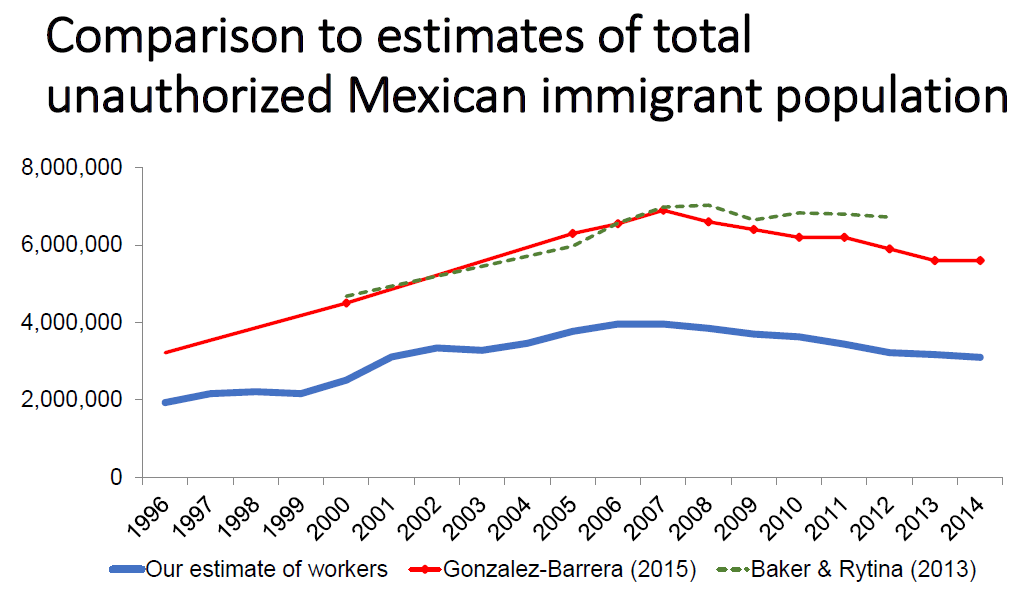

If we want to reduce unauthorized immigration into the United States, we need to stop the pull magnet, and we need to provide employers with better legal ways to get the workers that they want. We need visa portability and automatic adjustment of visa numbers over business cycles (Chart 5). The other thing is, we do have this shrinking stock of unauthorized immigrants who are already here. Many of them are working, and so one thing we might strongly want to consider is legalizing this population, enabling them to move more easily across jobs, to have better futures for themselves and their U.S.-born children.

Chart 5