Consumers’ and economists’ differing inflation views can complicate policymaking

Economists and consumers likely think of different concepts when they consider inflation. Economists typically focus on the underlying trend that monetary policy can steer. U.S. consumers appear to think instead about unpredictable changes in prices most relevant to their regular decision-making.

These dual views may be because monetary policy has successfully kept underlying inflation low and stable. This reality also has important implications for any policy strategy that relies on changing the public’s inflation expectations.

Sources of inflation

Inflation over long horizons (10 or more years) is largely determined by the actions of the central bank and the public’s expectations of policymakers’ future actions. At the frequency of business cycles (varying from one to 10 years), inflation is influenced by the amount of slack—or spare productive capacity—in the economy. This cyclical component of inflation increases during expansions and falls during recessions.

Such demand-driven inflation tends to increase prices and incomes with limited impacts on consumers’ real purchasing power. Economists tend to focus on these two drivers of inflation because central banks have little control over other sources—for example, disruptions to specific markets such as the oil market. Additionally, these other sources are not systematically predictable at a horizon beyond a few quarters. This is why measures of core inflation, such as trimmed mean personal consumption expenditures, are followed closely.

However, consumers appear to be more attentive to the volatile component of inflation that measures of core exclude. One potential explanation is that consumers are more likely to recall extreme price changes and fail to recall the more stable prices that make up a larger share of their expenditures. This type of inflation does not broadly increase income and represents a decrease in consumers’ real purchasing power. It can be thought of as supply driven.

Assuming the central bank keeps core inflation stable and close to its target, as the Federal Reserve has done over the past several decades, periods of high or low supply-driven inflation are more relevant to consumers’ well-being and decision-making than subtle movements in core inflation. Thus, supply-driven inflation may be what typically comes to mind when consumers hear the word inflation.

Survey evidence of consumer expectations

The University of Michigan has conducted a monthly survey of consumers since 1990. The resulting indexes of consumer sentiment and consumer inflation expectations series are widely followed. The survey also includes many other questions related to consumers’ current situations and expectations. Analyzing the responses provides insight into formation of these expectations.

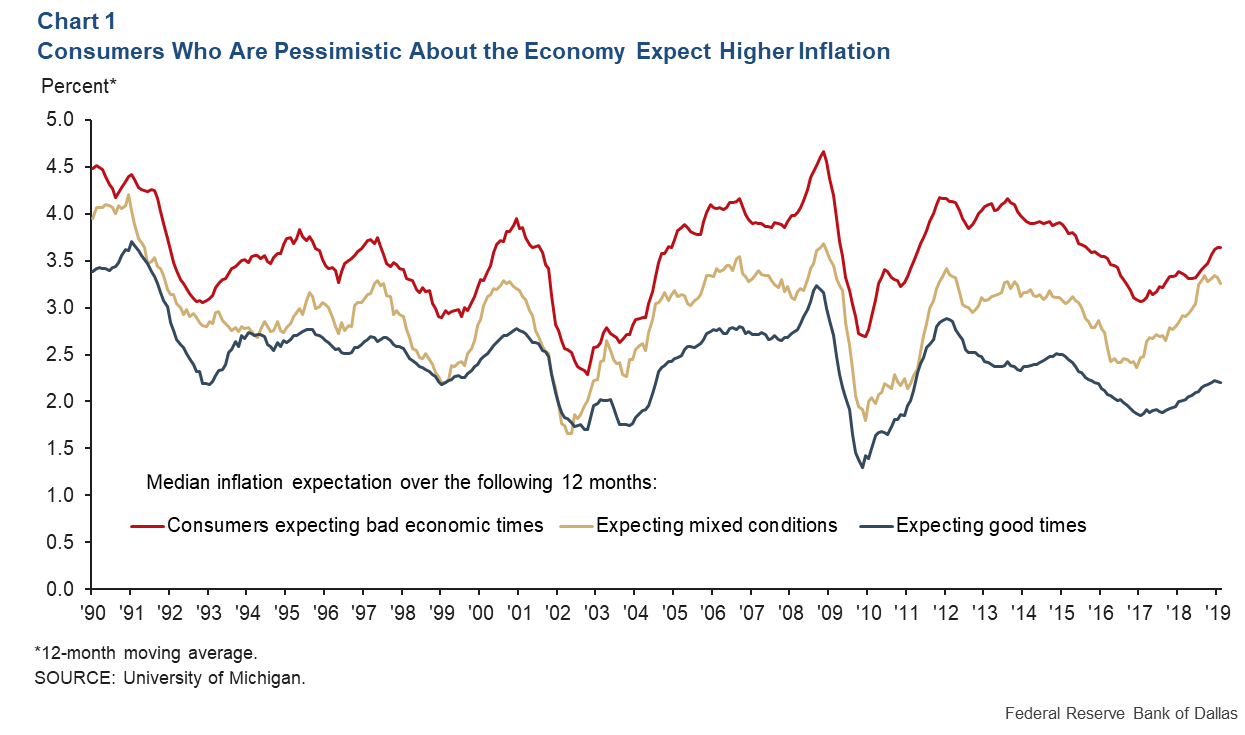

One survey question is: “Now turning to business conditions in the country as a whole—do you think that during the next 12 months we'll have good times financially, or bad times, or what?” Chart 1 plots consumers’ median expected rate of inflation over the next calendar year, according to how they answered this question.

Those who are pessimistic about business conditions consistently have higher inflation expectations than those who are optimistic about the following year. Inflation expectations of those with a mixed assessment of the economic outlook fall between the two groups.

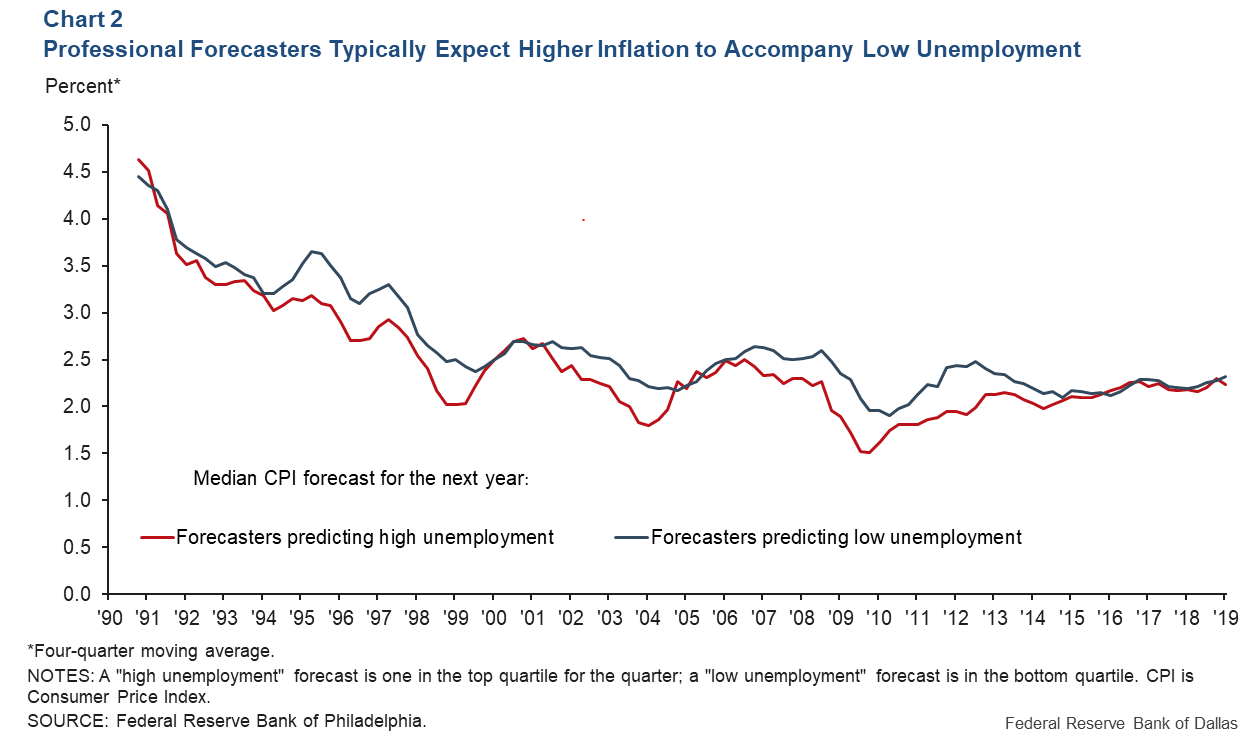

This is the opposite pattern of what you would find in a survey of economists. Chart 2 plots the median inflation expectations for the next calendar year from the Survey of Professional Forecasters, which covers those whose forecast of unemployment is in the top quartile and those whose forecast is in the bottom quartile. Although inflation expectations are similar over the past several years, the more pessimistic forecasters typically expect lower inflation.

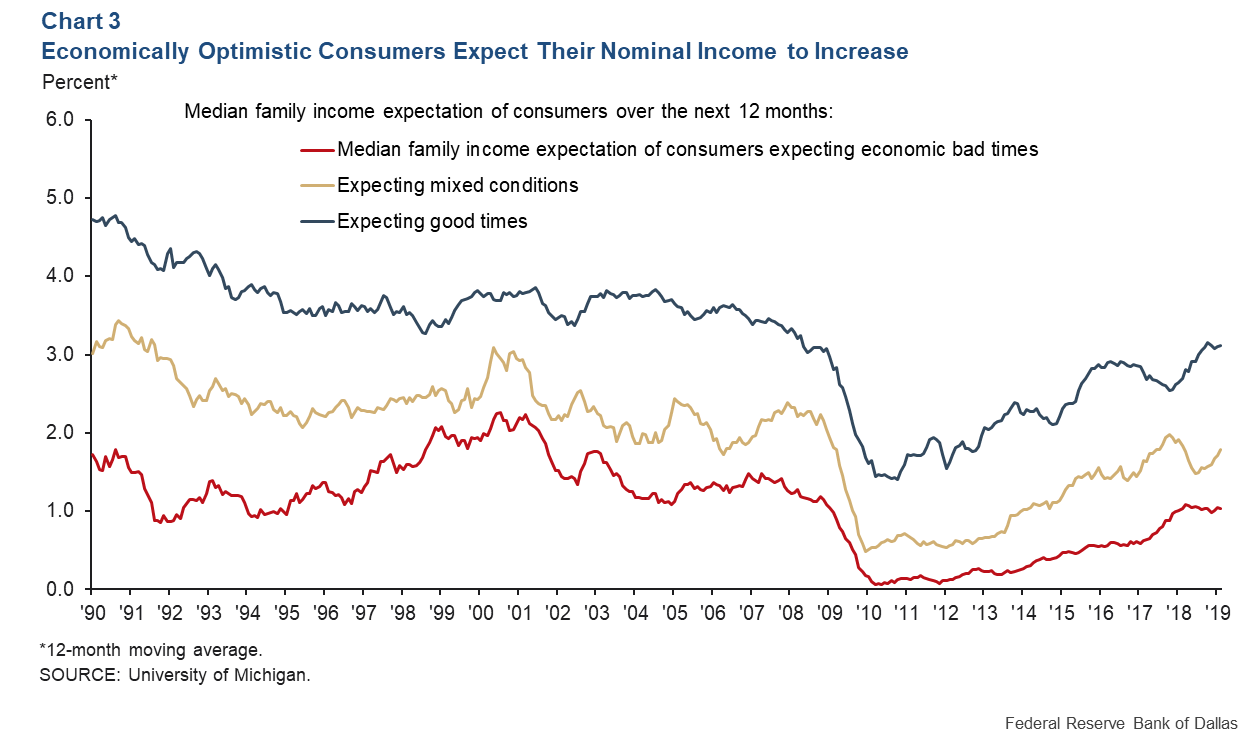

This result in the University of Michigan survey is carried through to other questions on optimism, such as expectations of real income, changing the forecast horizon from one to five years, and analyzing how optimism and inflation expectations change in a follow-up survey six months later. Chart 3 shows that the opposite pattern is true for nominal income—the optimistic respondents have higher expectations for their nominal family income than do the pessimistic respondents.

Monetary policy implications

Regardless of what is driving this pattern of behavior, it has important implications for monetary policy. When constrained by the lower bound on interest rates, one potential policy tool is forward guidance—influencing the public’s expectations of how policy will behave once the constraint of near-zero interest rates is no longer binding.

In standard models, forward guidance stimulates economic activity by promising more expansionary policy in the future and allowing inflation to run above what would otherwise be preferable. This has led to proposals, such as price-level targeting, that emphasize increasing the public’s inflation expectations after inflation has run below target, which is more likely to occur when interest rates are stuck near zero.

However, if a typical consumer is only informed that inflation will be higher in the future, they would likely become more pessimistic about economic conditions, limiting the stimulative impact of the policy announcement. This strategy would require substantial communication and economic education efforts to inform the public that the higher inflation will be driven by expansionary monetary policy and increased resource utilization rather than supply disruptions that reduce real purchasing power.

An alternative strategy proposal is nominal income-level targeting, which aims to stabilize expectations of income rather than prices. It shares many of the theoretical benefits of price-level targeting. However, a policy announcement intended to increase nominal income expectations would be less likely to be interpreted as bad news by the public, which already associates higher nominal incomes with economic good times.

About the Author

The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.