Early mandated social distancing does gest to control COVID–19 spread

The COVID-19 pandemic has claimed more than 350,000 lives globally while causing unprecedented and widespread disruption to the world economy.

China responded to the initial outbreak with draconian mandatory social distancing policies in late January. Other countries adopted less extreme responses, either by deliberate choice, as in the United States, or because of implementation constraints, as in some European countries.

Viewing this range of actions, we argue that differences in mandated social distancing policies across countries have contributed to a wide disparity in epidemic outcomes.

Voluntary social distancing and a lack of compliance with mandated polices have led to unnecessarily high infection rates and death tolls in a number of countries. In our working paper, we contrast government-mandated social distancing policies with voluntary self-isolation in a standard model of epidemic spread, the Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) model.

Reluctance to accept self-isolation in early stage

Individuals are likely to isolate voluntarily when the probability of contracting the disease is sufficiently high. However, people also weigh the contagion risk against loss of income and the inconvenience of living in isolation. As a result, voluntary social distancing keeps people at home only when the infection risk becomes visible, and the epidemic has already taken off. This is too late to flatten the curve, with little or no effect during the accelerating stage of the epidemic.

We provide estimates of the number of days for patients to recover or die (the so-called removal rate) and the rates of exposure—by which we mean individuals who are not isolated and, therefore, could contract the virus. We use daily data on confirmed, recovered and death cases for Chinese provinces and other countries from the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center database.

To address the likely biases associated with limited and non-random testing, we allow for both systematic and random measurement errors. We show that the degree of social distancing can be identified up to a scaling factor, which is linked to the fraction of undetected cases in the population.

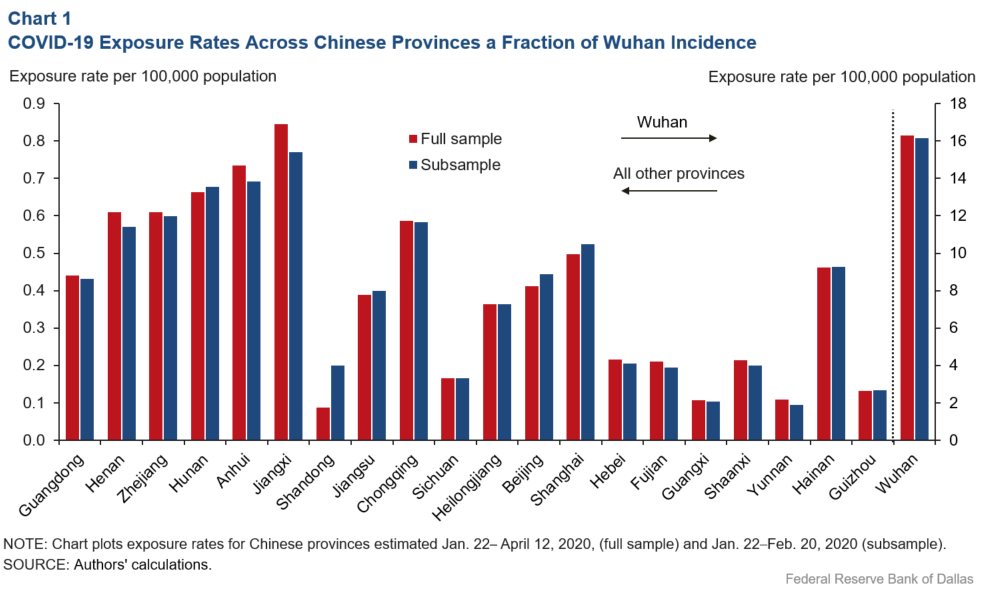

The share of exposed population is estimated to be very small for Chinese provinces excluding Hubei, the epicenter of the pandemic, even after allowing for a 50 percent under-recording of asymptomatic infections and errors in measuring recovered cases.

We estimate the share of exposed population across China at 1/60 to 1/40 the share in the Hubei epicenter province, of which Wuhan is the capital (Chart 1). This is an astonishingly low rate and is consistent with dramatically falling estimates of the effective reproduction rate at the onset of the pandemic in China, reported in the medical literature.

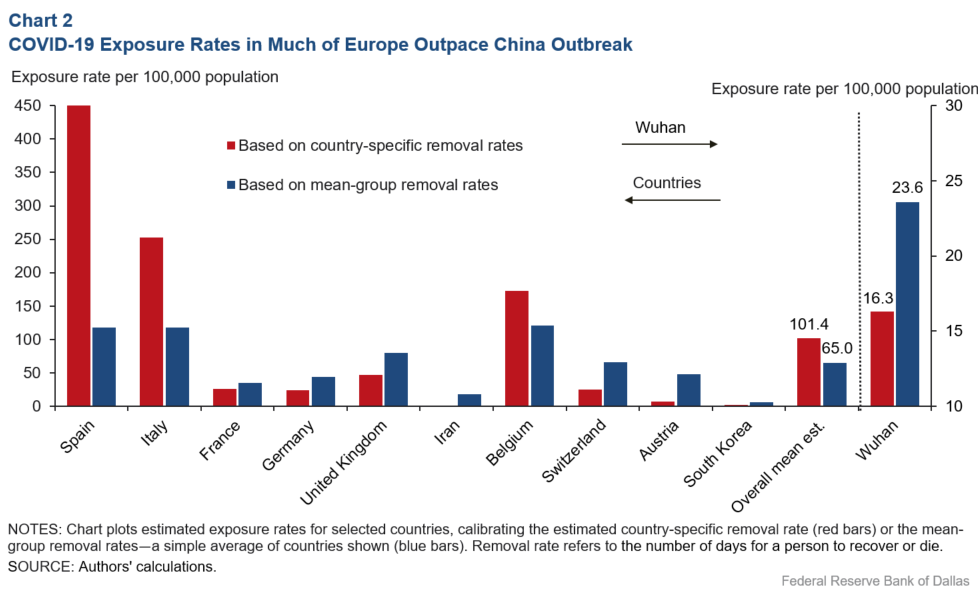

Moreover, and most unfortunately, estimates of the exposure rate in other countries are much higher— three to six times higher than in Hubei—despite the lead time that these countries had to prepare for the pandemic.

The country-specific estimates in other countries are much more heterogeneous, with Iran, South Korea and Austria doing relatively better, and Italy, Spain and Belgium displaying the highest exposure rates. However, these estimates are based on limited data and should be viewed as preliminary and only indicative (Chart 2).

Benefits of mandatory measures

We conclude that voluntary social isolation is ineffective, and mandated social distancing is required from the early onset of the pandemic to flatten the curve and slow the spread of COVID-19. We find the exposure rates to be similar across Chinese provinces outside of Hubei, and highly heterogeneous across other countries, largely reflecting the mandated level of social distancing.

While mandated social distancing is costly in terms of employment and lost output, targeted policies, applied consistently within and across countries, can mitigate the short-term costs and allow a more orderly return to normalcy.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.