Biden student loan relief plan allows increased borrowing, less repayment

Student loans make up the nation’s second-largest type of consumer debt with 43 million borrowers owing $1.6 trillion, trailing only mortgages.

After COVID-19 upended the U.S. economy in March 2020, federal student loan payments and default collections were suspended and interest waived. These pandemic accommodations have been extended seven times and are now scheduled to end Dec. 31, 2022.

A report from the credit reporting agency Equifax anticipates that once repayments on federally backed loans resume, they will cover almost $900 billion in student obligations for an average monthly payment of $244. Although most borrowers likely won’t encounter difficulties making payments initially, delinquency rates on student loans in repayment hovered around 30 percent before the pandemic.

The Biden administration recently announced new student loan relief, including canceling at least $10,000 in federal loans for borrowers making less than $125,000 ($250,000 for married couples) and more for Pell Grant recipients (undergraduates with extraordinary need). The White House estimates the plan will cost at least $240 billion, raising equity and inflation concerns. Some details are unclear; the final rule and implementation plan will be issued following a public comment period.

Income-based repayment plan participation rises

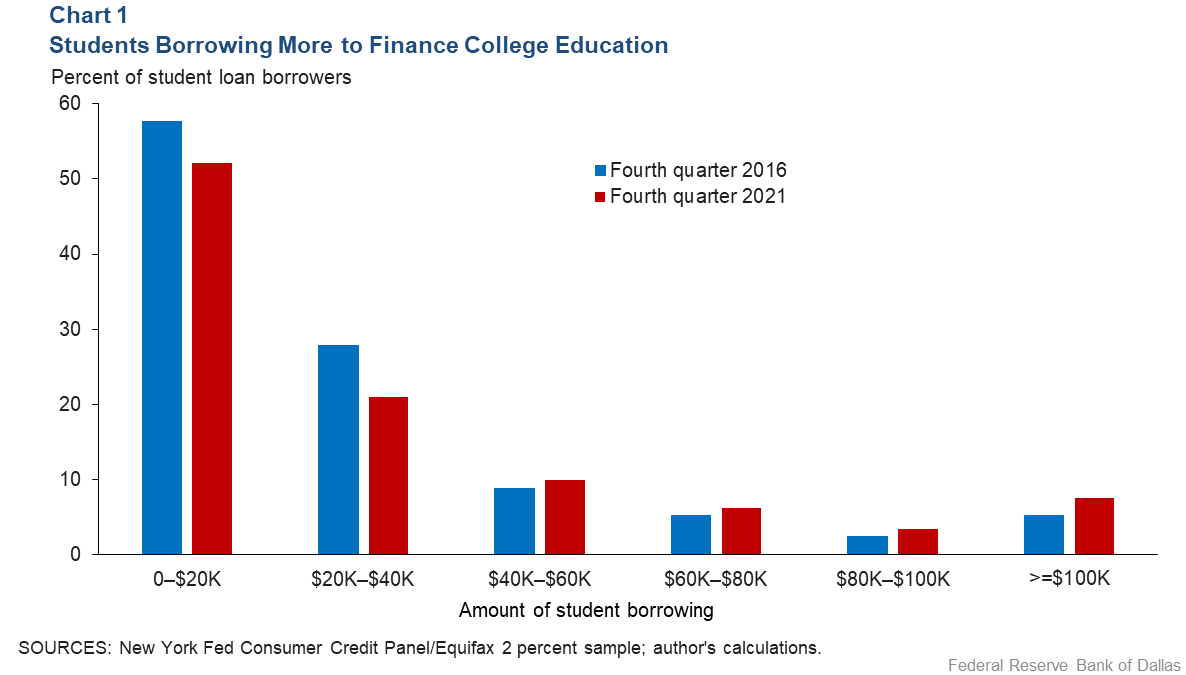

Student loan balances have been growing, a trend largely reflecting college tuition increases. The average student loan balance increased by nearly $7,000 from fourth quarter 2016 to more than $36,000 in fourth quarter 2021, according to an analysis of the most recent reliable data from New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax, a nationally representative anonymous sample of 5 percent of U.S. consumers with a credit file.

The share of borrowers with more than $50,000 in student loan debt rose from 16.6 percent to 21.4 percent during that period, though most borrowers’ obligations were less than $20,000 (Chart 1).

To afford larger loans, many borrowers have opted out of the standard 10-year repayment plan to choose extended, graduated or income-driven repayment (IDR) plans that provide lower initial monthly payments and loan forgiveness after 20 or 25 years of payments.

The share of federal student loan borrowers in the IDR plans increased from 26 percent in 2016 (accounting for 44 percent of loan balances) to 34 percent in 2021 (accounting for 55 percent of loan balances).

The Biden administration’s newly announced plan includes new rules for IDR repayment plans that aim to further reduce the burden on borrowers and lower defaults. The plan cancels outright some student loan debt for most borrowers; this is in addition to IDRs that already include loan forgiveness provisions. In sum, the Biden plan makes future repayment much less costly for borrowers and alters the payment dynamics for many.

Longer payments though not much paid down

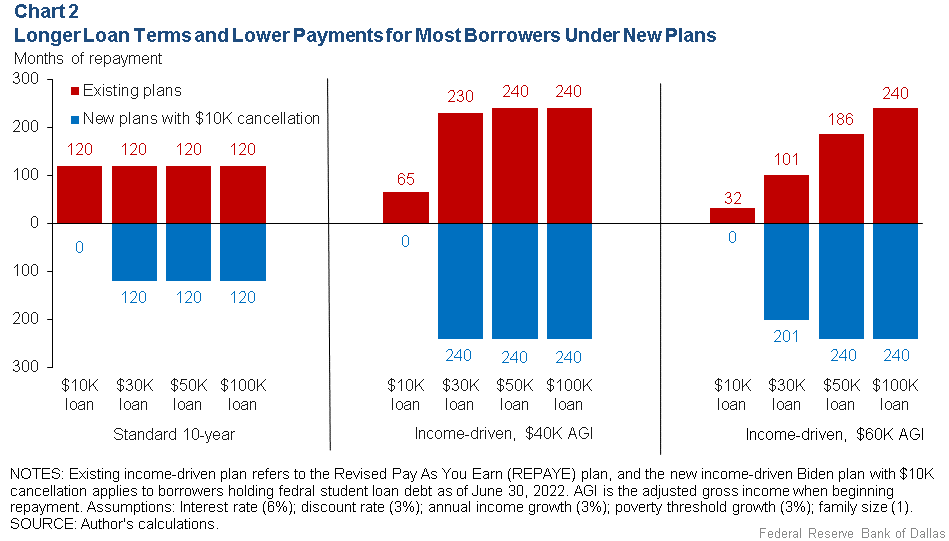

The standard 10-year repayment plan requires 120 fixed monthly payments to cover principal and interest. In contrast, the payment schedule of existing IDRs differs by plan, loan amount and borrower income.

Under the most-popular existing pre-Biden plan—Revised Pay As You Earn (REPAYE)—borrowers pay up to 10 percent of discretionary income—defined as the amount of income above 150 percent of the federal poverty line. (The 2022 poverty threshold is $13,590 for individuals, $23,030 for an individual with two children and $27,750 for two people with two children.)

Payment amounts are recalculated annually as the borrower’s income and family size change. Loans are forgiven after payments have been made for 20 years (undergraduate study) or 25 years (graduate or professional study). Higher-income and lower-debt borrowers pay loans off faster and thus are less likely to get loans forgiven (Chart 2).

The new plan calls for $10,000 in debt forgiveness and requires lower monthly payments for participants. Meanwhile, borrowers pay up to only 5 percent of discretionary income—now defined as income above 225 percent of the federal poverty line—and the unpaid interest is no longer added to the loan balance.

The balance for those borrowing less than $12,000 is forgiven after payments for 10 years, compared with the former 20 years. Repayment is often lengthier because for most borrowers, the accumulated payments fall below the loan amount or even the interest owed before reaching forgiveness.

Costs differ by repayment scenario under existing plan

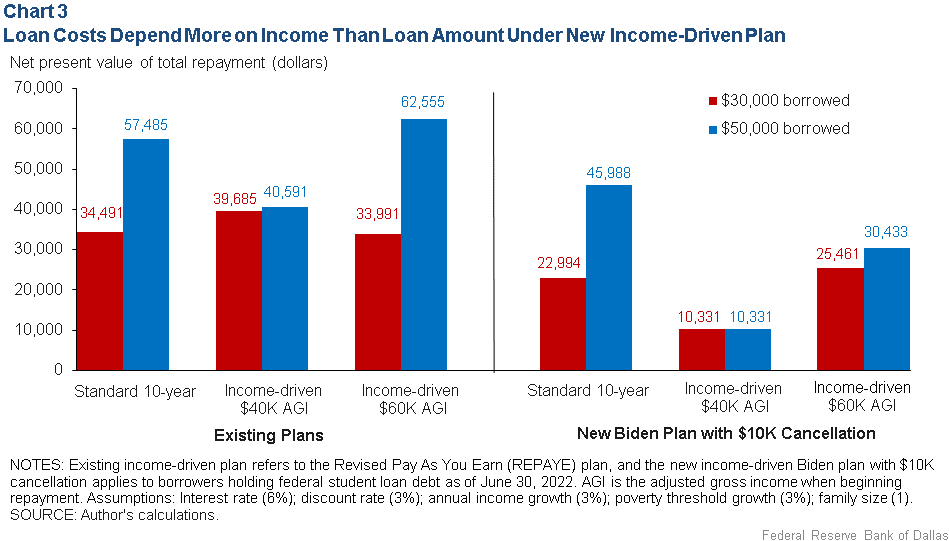

Because of inflation and the resulting adjustment of the poverty threshold, it’s helpful to look at real student loan costs in today’s dollars—the net present value. The left panel of Chart 3 illustrates the simulated net present repayment values for borrowers; two income levels and two loan amounts are depicted.

For those borrowing $30,000 and earning $40,000 in initial adjusted gross income (the total of all income less tax deductions), REPAYE costs $5,194 more than the standard 10-year plan because of higher interest payments over a longer time.

But for REPAYE participants borrowing $50,000, loan cost rises by just $906 (relative to those borrowing $30,000)—much less than under the standard fixed-amount repayment plan.

The net present value would not exceed $40,591 no matter how much more debt is borrowed for those initially earning $40,000 in adjusted gross income because the program requires 240 payments before the remaining balance is forgiven. The larger the loan, the more that is forgiven.

For REPAYE participants making $60,000 in initial adjusted gross income, paying off a $30,000 loan only lowers the loan cost slightly relative to the standard plan. With a loan of $50,000, however, making income-based payments would cost significantly more than the standard plan because repaying takes longer, though not long enough for any forgiveness provisions to apply.

REPAYE is therefore a preferable plan for lower-income borrowers with larger debt. Even under the old plan, borrowers with discretionary income under 150 percent of the poverty line can forego payments and have all loans forgiven. Due to the unlimited forgiveness at the end of the payment period, the program risks incentivizing borrowers to take on outsized debt, seek lower-paying jobs or become comparatively less engaged in the labor force—a moral-hazard issue.

Among borrowers on IDR plans, 31 percent won’t repay any debt because their income-based payment is less than the interest, a JPMorgan Chase Institute study found. Ironically, the study also noted that low-income borrowers who are eligible and could benefit most from IDRs are less likely to enroll and, therefore, spend a much greater share of their take-home income on student loan repayment.

Costs largely depend on income under the new plan

Under the Biden plan, with federal $10,000 loan forgiveness and other provisions in the income-driven repayment, standard-plan participants receive the same amount of principal reduction (net present value of $10,000) regardless of loan size if they borrow $10,000 or more. A borrower with less than $10,000 in debt will get less than $10,000 in relief. And those who already paid off their loans get nothing.

There are fairness concerns among borrowers who participate in the new IDR plans as well. If all borrowers can also participate in the new IDR plan (as shown in the right panel of Chart 3), the net present values of repayment are the same ($10,331) for borrowers earning $40,000 initial AGI regardless of loan amount because they make the same payments for 20 years based on income.

For higher-income or lower-debt borrowers, the relief could reduce the payment length and total interest paid. For borrowers earning $60,000 initial AGI, borrowing $30,000 and receiving the $10,000 cancellation, their loan is paid off in 201 months. The net present value of the loan cost is $25,461; their maximum cost remains $30,433 if they borrow more than $23,000 because payments are determined by income and not by the amount owed.

The new plan is expected to boost participation in the IDRs that lower the payment burden. Imposing a cap on a borrower’s income to qualify for cancellation or increasing the cancellation amount for low-income borrowers could alleviate the regressive nature of broad loan cancellation.

However, if the future loan payment is largely determined by income and not amount borrowed, the new plan may exacerbate the moral-hazard issue where the rational borrower suppresses his income while increasing his debt in order to maximize the loan amount forgiven. This incentive problem along with the inefficient allocation of public resources are concerns.

In sum, the costs and distributional effects need to be carefully evaluated when making changes to the student loan program.

About the Author

Wenhua Di

Di is a senior research economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.