Panel 4: Economic Implications for the U.S. of a North America Without NAFTA or USMCA

USMCA Keeps the Peace, Fails to Improve on NAFTA

On Jan. 19, 2017, we had the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the TPP. The TPP was set to open up new markets for U.S. farmers and U.S. businesses, small, medium and large. It was designed to do everything NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement) did and more across the Asia Pacific region. Four days later, the U.S. quit the deal.

Today, we have a revised NAFTA in front of us. The revised deal does nothing for our U.S. farmers or businesses across the Asia Pacific region. So, today, I’m going to talk about the economic implications of a situation where the USMCA (United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement) does not pass and the U.S. does withdraw from NAFTA. The key takeaways are going to be the following.

First of all, the U.S. would lose preferential access in our two largest markets, as speakers today spoke about at length. It would be devastating, especially for the small- and medium-sized businesses that rely so much on recent developments in trade preferences. It would also be a strain on every culture for sure. Ironically, we could actually have free trade in autos—that could be a bright spot—but greater uncertainty overall.

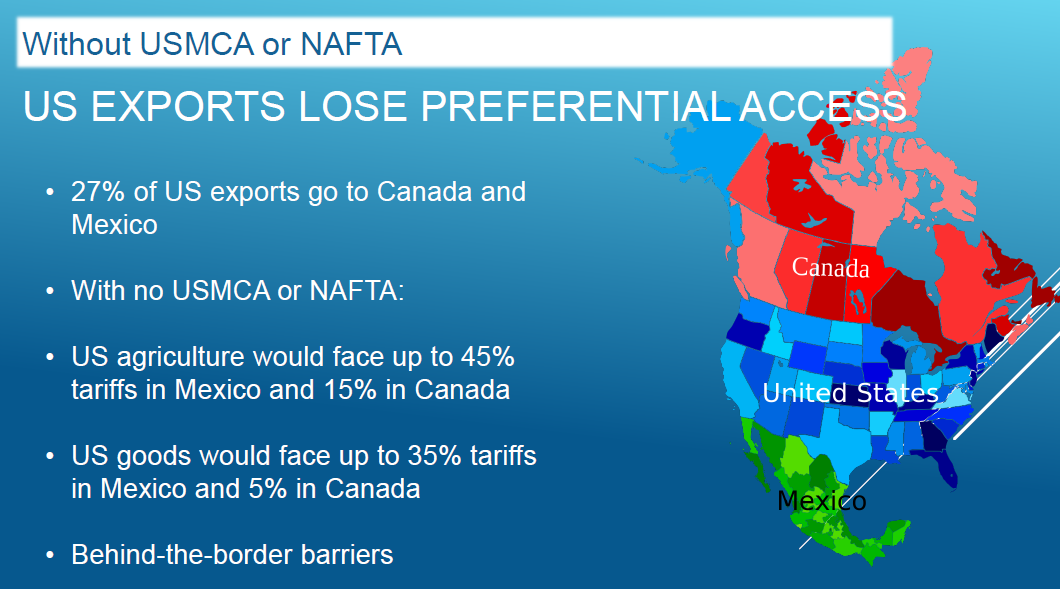

Without USMCA or NAFTA, U.S. exports lose preferential access to markets in Mexico and Canada, as you all know. Nearly 30 percent of U.S. exports go to these two markets, and we would be facing not only their MFN (most-favored nation) tariffs, but also bound tariffs (an additional tariff on specific goods that is above MFN rates), which could go as high as 45 percent for agricultural products in Mexico and up to 15 percent in Canada. Other goods could go up to 35 percent in Mexico and 5 percent in Canada (Chart 1).

Chart 1

Currently, about $740 million worth of U.S. beef exports, or 20 percent, go to Mexico duty free. Without NAFTA, without USMCA—so, with no deal at all—it would revert to a 20 percent tariff. Not only do we revert to a 20 percent tariff, but our competitors in Australia and Canada would continue to get zero tariffs. U.S. exports of beef would face those tariffs, plus all of those other messy, hairy things behind the borders that customs and retailers can do to foreign sellers.

We have Canada, where Canada has been opening its dairy market little by little over the past few years. It was not costless for them politically. Without a deal from the U.S., we would lose out on all those benefits. Right now, 7 percent of our dairy exports go to Canada, duty free. Without a deal, it would revert to not only an 11 percent tariff, but an additional $2 per liter of milk, and that translates into a pretty large ad valorem equivalent, plus there would be all of those non-tariff, behind-the-border retail and shelf issues.

Lastly, beer: Last year, about 21 percent of our beer went to Mexico duty free and the competitors, they face a 20 percent tariff. We’re talking about Belgium, Germany, Netherlands and the U.K. Without a deal, we would be facing that same 20 percent. Those are just three examples, but there are many more.

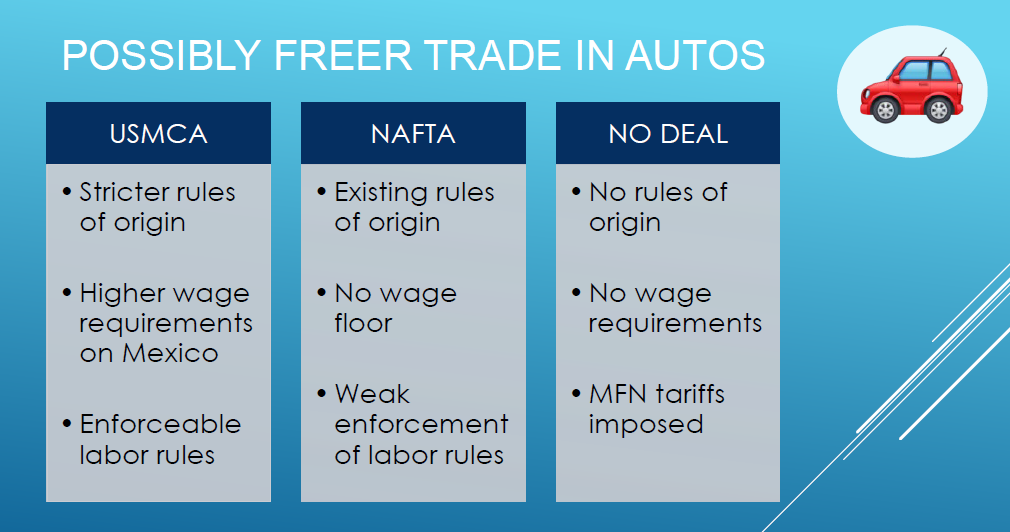

Now, let’s look at the bright spot. If there is no deal, there could actually be freer trade in autos by only paying the 2.5 percent MFN tariff. However, when you’re talking about the $20,000 to $80,000 automobile coming in, it still adds up pretty quickly. But there would be cost savings without rules of origin, so it could actually happen in the longer run. It could mean freer trade in autos. It might mean most production in autos stays in the U.S. It could also mean lower consumer prices for autos in the U.S.

I was just up in Traverse City, Michigan, last month and it was amazing. It was all those suppliers—the OEMs (original equipment manufacturers), the auto part suppliers. Detroit sees itself as the future of mobility for America and the world. But it doesn’t see a future in OEMS anymore. To them, it’s all digital, it is figuring out how to get people from A to B, and that does not always involve an automobile. It certainly doesn’t always involve manufacturing an automobile in the U.S.

So, I got this feeling that Detroit and the state of Michigan are so far ahead of where Washington is in thinking about the auto industry and the future of mobility. With USMCA, we see stricter rules of origin, higher wage requirements, which would hit Mexico, and strong and enforceable labor rules (Chart 2). With just NAFTA, we have those existing rules of origin—not as strict, but they’re still there—no wage floor and we’ve got weak enforcement of the labor rules. And with no deal at all: no rules of origin, no wage requirements, and we go back to a 2.5 percent tariff assuming that the U.S. respects the WTO bound levels.

Chart 2

If you assume USMCA will reduce policy uncertainty, then you get to a small, but positive, effect. I see USMCA as if it is NAFTA 0.8, but no deal at all is really 0.0, because really, losing all those preferential tariffs will be devastating for so many of our businesses and our farmers. When people say, “The USMCA is great, let’s pass it,” and you dig deeper, it’s usually because the alternative is Trump’s threat to withdraw. If it’s withdrawing from NAFTA or USMCA, of course, it’s going to be USMCA. That’s how I see this.

If you look at the deals that the U.S. has been doing or talking about doing, they are much more about damage control than they are about real market opening. If (only) the FTAs (free trade agreements) we are doing were really all about real market opening! But today, it’s really more about risk management, damage control and quelling uncertainty.

You look at the U.S.–Japan deal. What is Japan really getting from this deal? Why would they even do it? They’re doing it hopefully to get out of a [Section] 232 (national security tariff) on autos. Maybe they’re doing it just to keep the peace. But they’re really not getting anything out of it, if you look at the text. USMCA is not necessarily better than NAFTA. There is really no great market opening in there.