Panel 2: Services and Trade

Liberalizing Trade of Services Offers Potentially Large Economic Gains

Traditionally, when someone mentions international trade, the first thing that comes to mind is movements of goods—goods like agriculture; commodities like oil and steel; and maybe manufactured goods.

We’re moving stuff across borders, and that is how we think about international trade and underpins the way that we developed trade models. International trade is kind of really based on the physical nature of goods.

Governments have a long history of using trade policy in the form of tariffs and quotas to possibly protect certain industries in the goods sector or subsidies to promote manufacturing in the form of industrial policy, for example. To produce the good in one location and consume it in another, you need to move the stuff. There is a cost to doing it, and the further you want to move it, generally, the more costly it is. This is how we traditionally think about international trade.

We typically ignore services, assuming services are not tradable. An example would be a haircut. It’s produced where it’s consumed, and that’s true for a lot of types of services but not all. For example, transportation services. If you’re flying out on an international airline, you are consuming something that’s produced by residents in another location. Another example is international banking, such as consulting services via a multinational corporation, as well as consulting services for research and engineering.

The output for such services could be stored digitally and then moved across borders. You write some software code to do some calculations, and you could send the results to someone in another location. You’re still moving stuff, but it’s very different than physically moving goods. So, we need to think about services trade a little bit differently than goods trade.

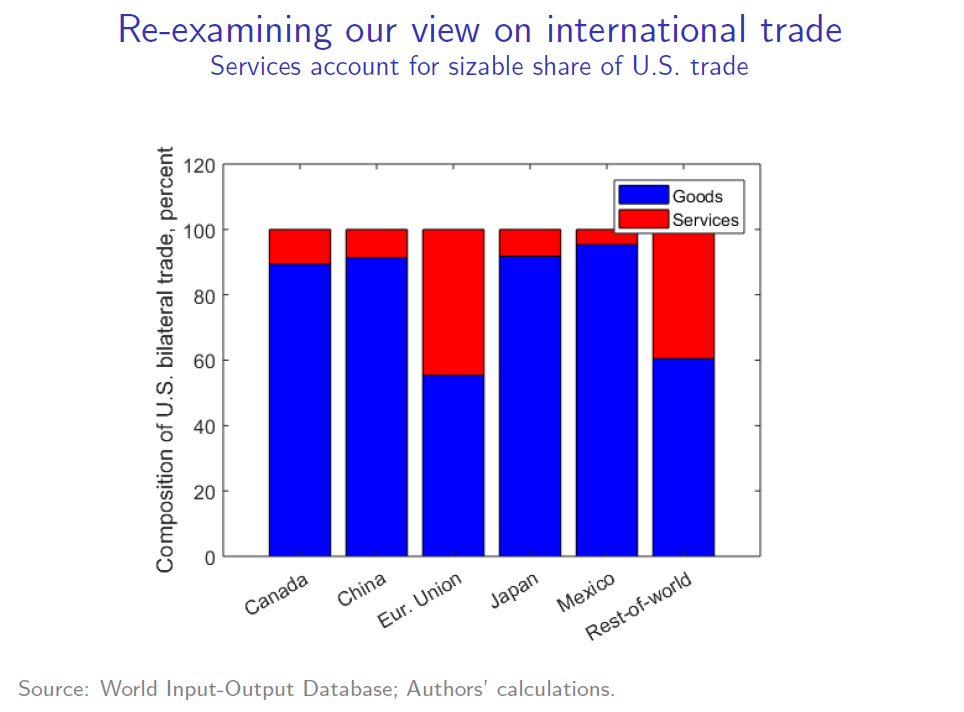

Chart 1 shows a breakdown of trade in goods versus services from the perspective of the U.S. with each of its main trading partners. Clearly, the majority of trade is still dominated by trade in goods, but services trade is non-trivial, particularly when you look at U.S. trade with the EU and trade with the rest of the world.

Chart 1

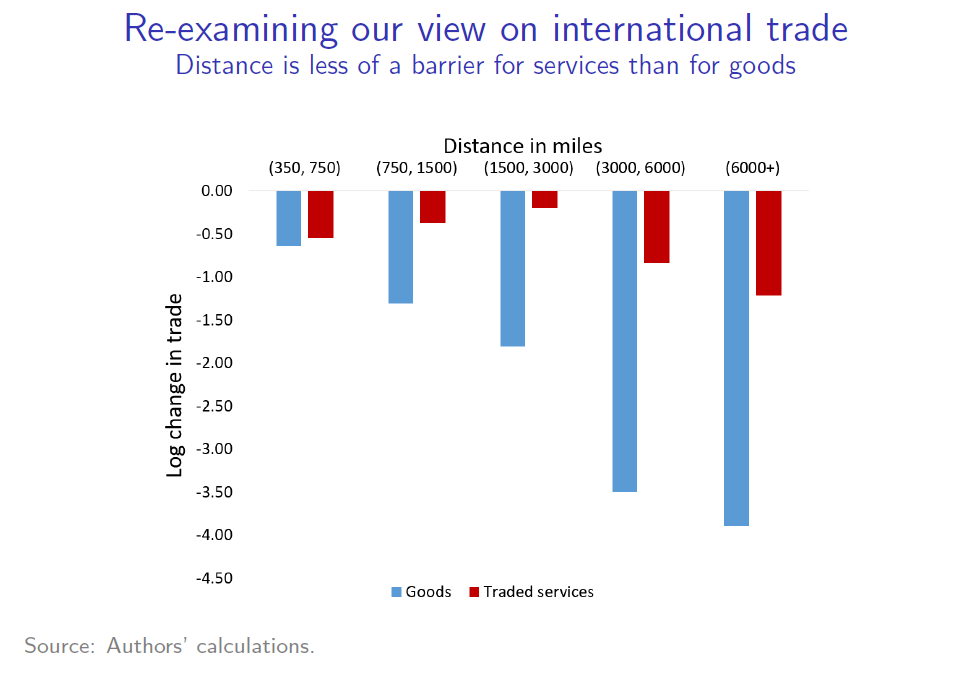

Services actually account for about one-third of U.S. exports. It’s not something we want to ignore when thinking about trade. Trading goods between the U.S. and Australia is very costly because you have to physically move stuff, but this is less true for digital information or a lot of services production. When sending something by email, it doesn’t matter if you are here in the same room with me or if you’re all the way in Australia.

Chart 2 shows the average effect of distance on trade flows. When you’re looking at goods trade, as the distance becomes greater, the amount of trade between those two locations declines very quickly. When you look at the same effect of distance on services trade, there is really not much of a difference whether we’re 6,000 miles apart or only 350 miles apart.

Chart 2

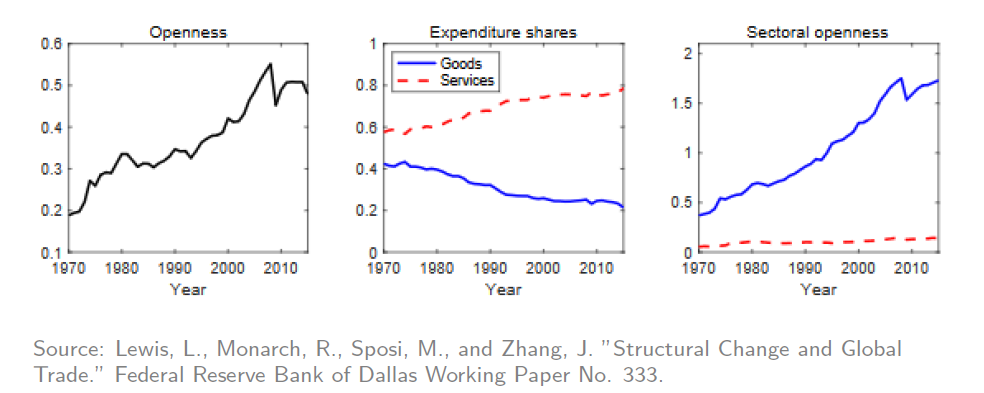

I want to shift now and put things into a more broad macroeconomic perspective. Trade has grown remarkably as a share of world GDP (gross domestic product). The share of trade over global GDP rose from 20 percent in 1970 to 50 percent today.

There have been several trends that have been very prominent features of the global economy. Trend No. 1: a massive increase in globalization. Trend No. 2 is something that economists refer to as structural transformation. The middle figure in Chart 3 demonstrates this process; there’s a very sharp shift in resources from goods to services. Services are occupying a greater share of expenditures globally, and the goods share has been declining. However, openness is much higher for goods compared to services and has been increasing much more rapidly over time.

Chart 3

Here, I have shares measured in terms of final expenditures. What I am measuring is final expenditures by households—the stuff that you purchase and consume day to day; fixed capital formation, spending on construction and other forms of investment like equipment and machinery; and government spending.

Goods are just the more open sector; a lot of stuff is being traded. What are the key drivers of openness? The impacts of declining trade barriers have come in many forms, including reductions in tariffs, making trade policy more transparent and declining physical transportation costs.

Standardized shipping containers and more efficient modes of moving goods from Point A to Point B have all resulted in more trade taking place. In addition, the industrialization of emerging economies has contributed to the increase in trade, as they have joined the global trading system. Globalization has lifted huge portions of the world’s population out of poverty, improved quality of goods, promoted competition, increased product selection and generally lowered consumer prices of goods. The gains aren’t shared equally by everyone, but this is, I think, a fairly uncontroversial statement to make: The aggregate benefits from trade have been positive.

Higher incomes and industrialization globally have resulted in greater income per capita. This additional income is being disproportionately spent on services relative to goods. As you get richer, you’re going to spend a greater share of your income on luxury goods as opposed to necessities but also consume more education, spend more on health care, go out dining, to entertainment—all service sector activity.

However, there is a differential in productivity growth between goods and services. Productivity growth has been much faster in goods-producing industries than in service-producing industries.

What does this mean? In the macroeconomic sense, this is going to result in a reallocation of resources from goods to services. Goods become more productive—you need to allocate fewer workers and fewer resources to the production of goods and reallocate them toward services. These resources are going to come with a cost—you pay a higher price for services over time compared with goods. This change in relative prices is also going to mean households’ budgets are going to be spent increasingly on services because they’re becoming more expensive.

Those are the drivers of structural change. The consequences are important in the context of thinking about openness. The economy is shifting from goods to services, but the service sector is not as open/tradable as the goods sector. It’s going to—all else equal—reduce openness or make the world look less open because we’re just consuming more and more of stuff that’s not traded as much, limiting the potential benefits you could realize from trade liberalization in goods.

We’ve already exhausted a lot of the scope that we have for reducing trade barriers on goods. Tariffs and quotas are extremely low. Even in spite of the recent protectionist policies, by historical standards, tariffs are still extremely low. There is some scope for liberalization, but it’s limited. In addition, policy could do very little about changing the cost of moving goods—the physical transportation cost part of it.

What can be done to increase openness and realize more benefits from trade?

I did some projections based on a recent working paper with some co-authors of mine, Logan Lewis and Ryan Monarch from the Federal Reserve Board of Governors and Jing Zhang from the Chicago Fed.

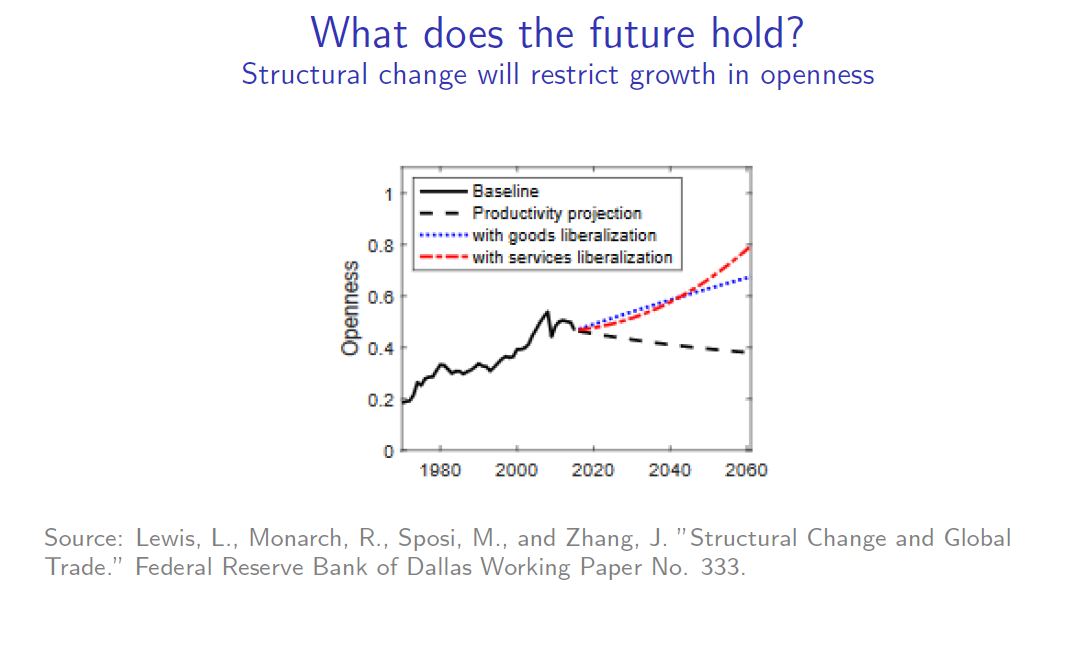

The first thing I want to point out in Chart 4 is to ignore the colored lines; look at the black line—that is the trade to GDP ratio; the solid part of it is what we observed already since 1970. The dashed line is based on a simulation or projection going another 45 years into the future. The assumptions that I’m building into this calculation are that, suppose there are no changes to trade barriers, either in goods or services, either up or down. Trade barriers are constant.

Chart 4

We also assume a differential in productivity growth between goods and services. The economy is gravitating continually away from goods toward services, and there’s no increase in trade. Trade as a share of GDP is going to fall because we’re going to just be consuming more stuff that’s less traded. What you see with the dashed line is a decline in world trade as a share of GDP.

We’re kind of limited to what we can do with trade policy on goods, but we should be thinking about what we can do with services trade. Services is 80 percent of the global economy; we should be seriously thinking about how we can benefit from trading these services. There are six chapters of the USMCA (United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement) that are either directly or somehow closely related to trading services. I want to give just a quick picture of how we think about the potential benefits from liberalizing trade in services.

Look at the colored lines in Chart 4. Let’s start with the blue one. This is the same projection exercise. We’re going to assume productivity growth is continuing at the same rate as it has in the past. And we’re going to assume that goods trade barriers somehow decline at the same rate that they have in the past, about 1.5 percent per year. The blue line shows openness is going to just continue increasing at pretty much the same trend rate that it has in the past. Alternatively, suppose there are no reductions in trade barriers for goods, but all of the attention is focused on liberalizing trade in services (red dashed line).

We’re going to reduce barriers for trade in services by 1.5 percent per year, just to make the calculations comparable. What you can see is that openness would increase productivity exponentially.

Why is that? There is a complementary effect of liberalizing services. We’re consuming them in greater proportions, and if we could reduce prices in services, improve the quality of services—and that’s the stuff that you’re consuming a majority of—then the benefits are disproportionately large from doing that rather than focusing on goods. Policy toward the liberalization of trade in services is something that we should really think about.