COVID-19, oil price collapse dimming outlook for banks in 2020

Weakened business finances, soaring unemployment and cuts to the federal funds target rate—products of the COVID-19 pandemic—have diminished the outlook for banks nationwide and in the Eleventh Federal Reserve District. In addition, lenders, especially those in the district, confront challenges from an energy sector collapse, one much more profound than the most recent 2015–16 oil price slump.[1]

Economic conditions are the biggest driver of bank performance. Underscoring the challenges are median projections from the Federal Reserve's June Summary of Economic Projections for a 6.5 percent contraction in U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) and a 9.3 percent U.S. unemployment rate this year.[2] Both fiscal and monetary policy have provided support to some businesses and households, and regulatory changes have aided banks, helping offset some of the pandemic’s economic impacts.

The banking sector appears better capitalized before COVID-19 than it was prior to the 2007–09 global financial crisis. Still, commercial real estate and many nonfinancial corporate sectors show signs of credit-quality deterioration, and sectors most dependent on consumer discretionary spending face significant headwinds. We expect bank profitability to decline, asset quality to weaken and bank capital to fall in 2020.

Falling Bank Profitability

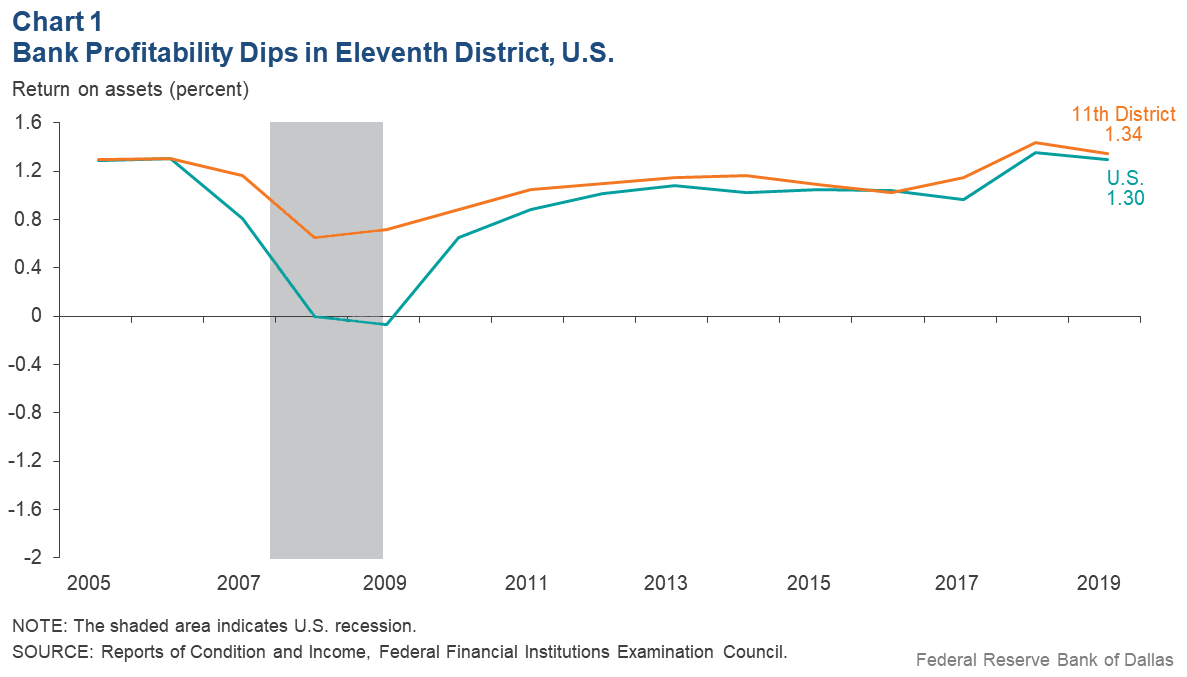

Profitability growth, while remaining high, had begun slowing in 2019. Eleventh District banks earned an annualized return on assets of 1.34 percent in 2019—down from 1.44 percent in 2018—while U.S. bank profits were 1.30 percent—down from 1.35 percent in 2018 (Chart 1). Lower net interest margins and higher expenses mainly drove the profitability decrease.

Net interest margins—the difference between a bank’s interest income (loan yields) and interest expense (deposit costs) weighted by average earning assets—were pressured in the second-half of 2019.[3] With three federal funds rate cuts in the latter half of 2019, loan yields fell more quickly than deposit costs, lowering banks’ net interest margins. With further rate cuts at the beginning of 2020, net interest margins are likely to decline further this year and reduce profitability.[4]

Asset quality overall was solid at the start of 2020. The district noncurrent loan rate—the percentage of loans past due 90 days or more or on nonaccrual status—measured 0.79 percent at year-end, about even with year-end 2018, the lowest such rate since 2007. The U.S. noncurrent loan rate was 0.89 percent, down from 0.97 percent at year-end 2018. Improvement in the credit quality of residential real estate drove improvement nationally.

Asset quality likely will deteriorate this year across loan types. The impacts will differ between banks in the district and the nation in part because of loan portfolio mix.

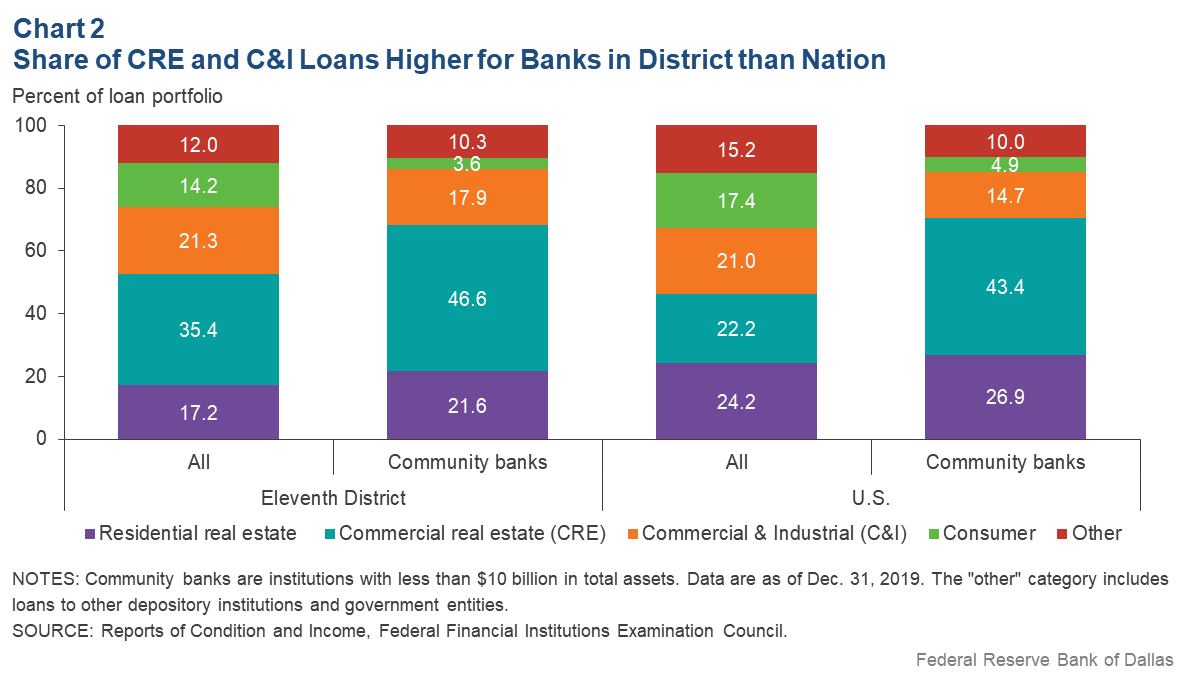

District banks are noticeably more concentrated in loans secured by commercial real estate (CRE) than those in the nation. CRE loans are those made for commercial construction and for the financing of shopping centers, office buildings and apartments. These loans make up 35.4 percent of bank loans in the district, compared with 22.2 percent nationwide (Chart 2).

Some CRE borrowers may struggle to maintain positive cash flow, with COVID-19 changing consumers’ activities and increasing work-at-home arrangements temporarily at some firms and permanently at others.

Additionally, the quality of commercial and industrial (C&I) loans will likely deteriorate. C&I loans include those to the energy industry and to business customers in COVID-19-affected industries such as restaurants and retail.

Worsening C&I loan quality could have a marginally larger impact on community banks in the district—institutions with less than $10 billion in total assets—relative to those in the rest of the nation. C&I loans account for a greater share of community banks’ lending portfolios in the district (17.9 percent) than in the nation (14.7 percent). Consumer portfolio credit quality, particularly credit cards, may also weaken this year, which would have a greater effect nationally.[5]

Overall bank capital levels—a bank’s assets less liabilities—increased in 2019. Equity capital was 11.8 percent of assets at the end of 2019, up from 11.4 percent at year-end 2018. Nationwide, the equity capital ratio rose to 11.3 percent from 11.2 percent a year earlier. The purpose of bank capital is to buffer against unexpected losses. Inadequate capitalization of banks can reduce overall credit availability and negatively affect the economy. While the banking sector was generally well-capitalized heading into 2020, unexpected losses due to deteriorating economic conditions from COVID-19 and energy sector strains could diminish bank capital later this year.

Energy Dims Outlook

Even before COVID-19, banks were confronting deteriorating energy sector conditions and outlooks. In late 2019, the credit quality of loans to the industry began declining, with energy firm defaults expected to increase in 2020.

A supply shock earlier this year, in part the product of a Saudi Arabia and Russia oil price war, further weighed on banks with direct lending to energy firms.[6] Lenders located in energy-producing regions were indirectly affected as the downturn touched area household and commercial customers.

Moreover, the pandemic created a negative demand shock for the energy industry. With people across the world facing shelter-in-place orders, demand for oil products such as gasoline and jet fuel declined dramatically. The decrease in demand, occurring simultaneously with a large supply increase, sank oil prices (see Go Figure).

West Texas Intermediate crude oil prices plunged in early 2020 to levels well below breakeven prices reported by regionally based energy companies.[7] In addition, oil prices are anticipated to remain below Eleventh District breakeven levels through year-end 2021. The concurrent demand and supply shocks could make this energy downturn worse than that in 2015–16, with more restructurings and bankruptcies anticipated in the sector.[8]

Because bank lending to energy firms is included in a bank’s C&I portfolio, deteriorating energy industry conditions will contribute to diminished C&I portfolio quality.

COVID-19 Crisis Changes

The COVID-19 pandemic has touched banks on a number of levels, notably complicating their ability to maintain operations and serve customers with employees’ movements limited by health concerns, social distancing guidelines and other restrictions.

Operational challenges are a significant concern. In some cases, banks conducted transactions only through drive-through windows; in other cases, they limited the number of customers in lobbies or allowed meetings by appointment only. Some branches were closed temporarily for deep cleaning. As a result, banks have encouraged customers to conduct business online when possible.[9]

Banks must also continue to monitor their customers’ financial standing. The crisis has materially affected corporate cash flows, and some businesses—and, in turn, households—may face repayment issues.

Vulnerable sectors include oil and gas, transportation, employment services, travel arrangements, and leisure and hospitality, a Moody’s Analytics report said.[10] Lending to firms in these sectors is included in banks’ C&I portfolios. Financing for these industries’ commercial construction and buildings/offices is included in banks’ CRE portfolios. Such lending, therefore, poses a challenge in a district with an outsized share of C&I and CRE loans in the portfolio mix.

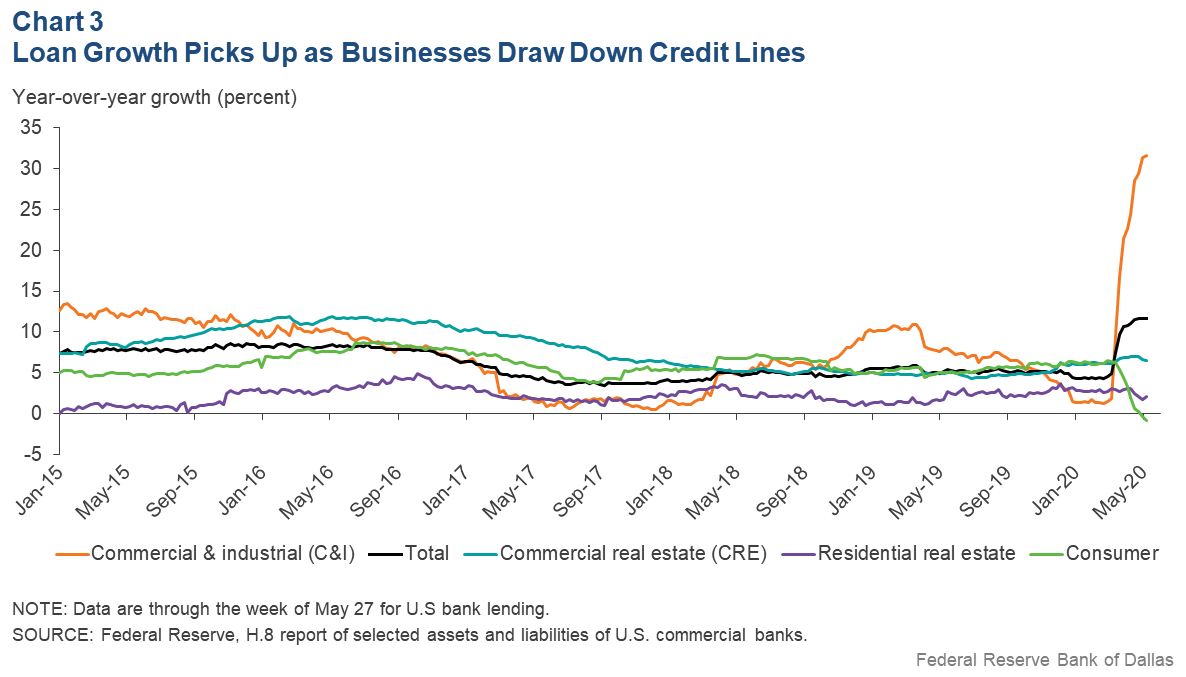

Nationally, bank C&I lending accelerated in late March and early April 2020 in response to the cash needs of corporate clients. While district lending data are only available quarterly, and with a lag, national figures can bring into focus COVID-19 lending trends.

These data show year-over-year loan growth jumped substantially during the last two weeks of March and continued to increase through the first two weeks of May, driven by a historic pickup in C&I loan growth (Chart 3). This was partly from corporate customers making large draws on existing credit lines, likely to have additional cash to buffer against COVID-19 strains.

From the week of March 11 to the end of April, C&I loan balances grew by over $600 billion nationally. Some of the growth may also be due to first-round Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans from the Small Business Administration, part of a congressionally approved stimulus package.[11] While PPP loans should present no repayment risk to banks—they are federally guaranteed—the drawdowns on existing lines could increase some banks’ C&I loan concentrations.[12]

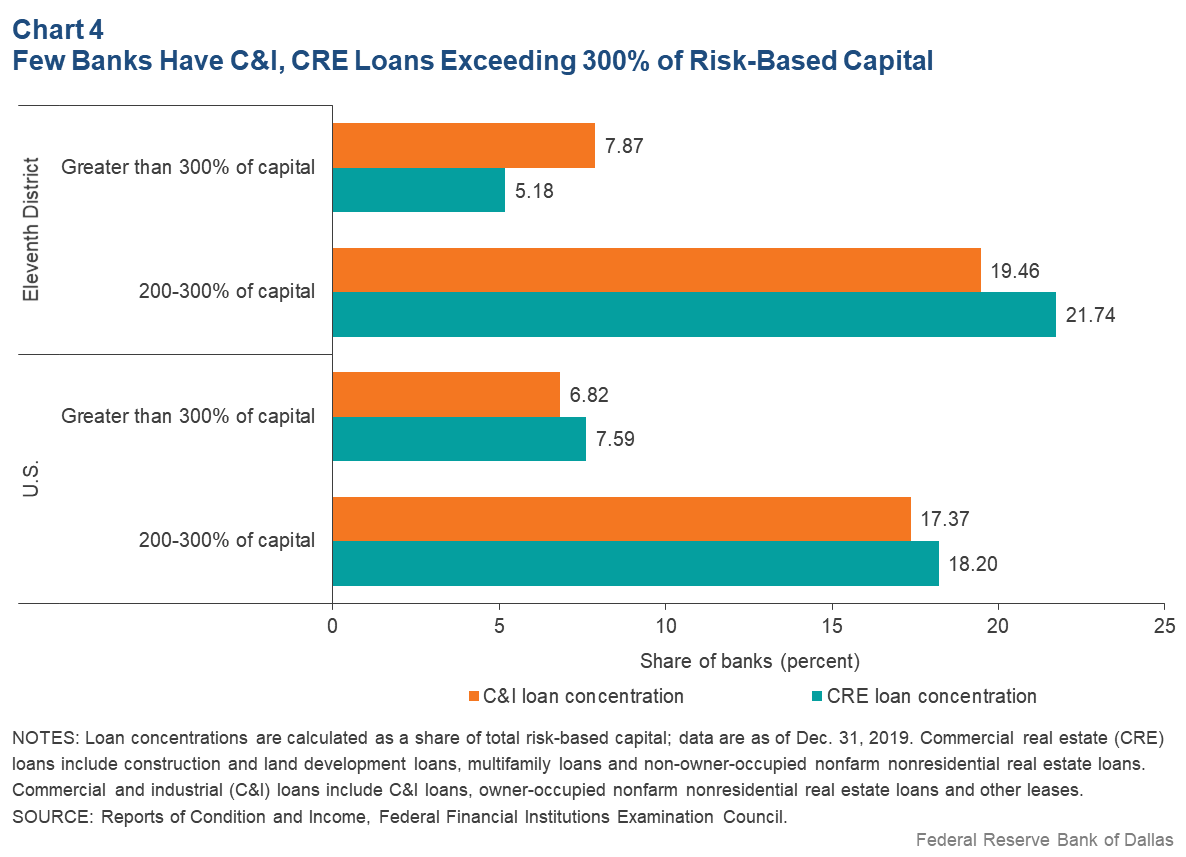

Another factor to consider when assessing a bank’s exposure is lending to vulnerable industries relative to capital levels. In the Eleventh District, 27 percent of banks have a C&I loan concentration greater than 200 percent of risk-based capital, the financial cushion available to absorb losses for a given level of risk (Chart 4).[13]

Nationally, 24 percent of banks have a C&I concentration exceeding 200 percent of risk-based capital. Some banks have even higher concentrations—8 percent of district and 7 percent of national banks’ C&I concentrations exceed 300 percent of risk-based capital.

For CRE loans, 27 percent of district and 26 percent of U.S. banks’ concentrations are greater than 200 percent of risk-based capital. Five percent of district and 8 percent of national banks have CRE concentrations greater than 300 percent of risk-based capital. The banks with higher proportions of C&I and CRE loans to capital may see their capital levels take a greater hit to resolve problem loans in these categories.

Official Crisis Response

A number of Federal Reserve and U.S. government programs began as the pandemic took hold in the U.S., including ones intended to support financial institutions. To enhance the liquidity and functioning of money markets and to support the economy, the Federal Reserve launched several facilities—special purpose vehicles or other entities for providing credit—and is supplying trillions of dollars in loan support.[14] The Federal Reserve, along with the other federal bank regulatory agencies, eased capital rules so that financial institutions could utilize and support the functioning of these facilities.

Bank regulatory agencies also issued policy statements encouraging banks to work with COVID-19-affected borrowers, providing flexibility to mortgage servicers and supporting banks that choose to use their capital and liquidity buffers to lend and undertake other supportive actions in a safe and sound manner.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act approved in March, which included the Paycheck Protection Program, also reduced the amount of regulatory capital banks must hold. The Federal Reserve, along with the other federal bank regulatory agencies, temporarily lowered the community bank leverage ratio requirement for banks with less than $10 billion in total assets, granting relief by decreasing the capital these institutions must hold.

In addition, a required new loan-loss accounting standard was delayed. Banks that were originally required to adopt the new standard in 2020 no longer need to, potentially reducing the amount of capital they must hold. They can, however, choose to adopt the new standard this year, which some banks are doing, as indicated on first-quarter earnings calls. Because of the reduced capital banks must hold, they may increase lending to businesses and consumers.

In addition to changes to capital and liquidity requirements, the Federal Reserve also encouraged financial institutions to participate in the CARES Act’s small business programs, including PPP lending.[15]

Looking Ahead

The banking sector ended 2019 generally on solid footing. Before the arrival of COVID-19, direct and indirect energy sector exposure had begun to weigh on some banks, as had reductions to the federal funds rate, which pressured net interest margins. The outlook dramatically changed in first quarter 2020. The pandemic reduced cash flows for many businesses and consumers and will likely cause loan losses. Fiscal and monetary stimulus and regulatory changes should help banks and borrowers respond to these challenges.

Notes

- Eleventh District banks are headquartered in Texas, northern Louisiana or southern New Mexico.

- See Federal Open Market Committee projections materials, Federal Reserve Board of Governors, June 10, 2020.

- Earning assets are assets on which banks earn income; e.g., loans and securities. Earning assets exclude, for example, the value of the bank’s premises and cash in the vault.

- Most institutions that publicly reported first-quarter earnings noted a decline in earnings. First-quarter regulatory data for all commercial banks was unavailable at the time of writing. The filing deadline for bank regulatory data for institutions with $5 billion or less in total assets during the first quarter was extended due to the COVID-19 crisis. See www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20200326b.htm.

- Consumer loans account for 17.4 percent of total loans nationally and 14.2 percent at district banks; credit cards account for 9.0 percent of total loans nationally and 5.4 percent at district banks.

- See “How the Saudi Decision to Launch a Price War Is Reshaping the Global Oil Market,” by Lutz Kilian, Dallas Fed Economics, April 2, 2020.

- The breakeven price is the oil price at which production becomes profitable.

- See “Heavily Indebted U.S. Upstream Industry on Track for Record Number of Chapter 11 Filings in 2020,” Rystad Energy press release, April 3, 2020.

- The American Bankers Association has been detailing the industry’s response to COVID-19 on its website, which notes that banks have instructed customers on how to utilize mobile and digital banking platforms. The notice, which the association has been updating, includes information on what individual institutions have done. See www.aba.com/about-us/press-room/industryresponse-coronavirus.

- See “COVID-19: A Fiscal Stimulus Plan,” by Mark Zandi, Moody’s Analytics, March 2020.

- See “Small Business Hardships Highlight Relationship with Lenders in COVID-19 Era,” by Wenhua Di, Nathaniel Pattison and Chloe Smith, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, this issue.

- See “Federal Bank Regulators Issue Interim Final Rule for Paycheck Protection Program Facility,” joint press release from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, April 9, 2020.

- Specifically, risk-based capital is a method of measuring the minimum amount of capital (assets less liabilities) required by regulation to support an institution’s operations. The calculation is based on riskiness of the lending portfolio given the institution’s size.

- For more information, see the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System’s Funding, Credit, Liquidity, and Loan Facilities webpage.

- See Federal Reserve Supervision and Regulation letter 20-10: Small Business Administration and Treasury Small Business Loan Programs.

About the Authors

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2020/swe2002.