Black workers at risk for 'last hired, first fired'

The COVID–19-induced global economic downturn shuttered businesses that have begun slowly reopening and reassessing whether to recall laid-off employees.

If these firms use job seniority as a criterion for returning to work, individuals most recently hired may be at greater risk of prolonged unemployment. In the U.S., black unemployment rates have spiked much more than white jobless rates during recessions.

Additionally, black unemployment rates tend to more slowly recede, a phenomenon encapsulated in the phrase “last hired, first fired.”

High Unemployment Legacy

In the years leading up to the Great Depression (1929–39), blacks held mostly low-skilled jobs that subsequently either went away or were filled by whites in need of employment during the tough times. The black unemployment rate was approximately 50 percent in 1932, more than twice that of whites, according to the Library of Congress.[1]

Despite the passage of time and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned employment discrimination based on sex, race, religion and national origin, blacks still suffer more adverse labor market outcomes, including higher unemployment, than whites. This gap widens during recessions.

For example, black “prime-age” workers (ages 25–54) experienced declining employment rates associated with the Great Recession (2007–09) two months sooner and 15 months longer than did whites. In the aftermath of that downturn, black employment rates dropped to a low of 66.7 percent in October 2011, while the low for whites, 76.5, percent occurred in July 2010.[2] Moreover, it took blacks longer to find new jobs than whites afterward.

History Repeating Itself?

The benefit that blacks received from the tight labor market in recent years may dissipate as the economy falters. Measures to slow the spread of COVID–19 “paused” many businesses or left them with reduced staffing, often favoring the retention of employees who can work from home.

A Dallas Fed study found that only 38.8 percent of full-time U.S. workers had remote-compatible jobs, compared with 37.3 percent in Texas.[3] Within the state, 33 percent of blacks hold jobs suitable for working from home, compared with 47 percent of whites. The study separated workers based on the fraction of occupational time spent sitting, kneeling or twisting the body; the prevalence of email usage; and an occupational requirement to work within arm’s length of another person.

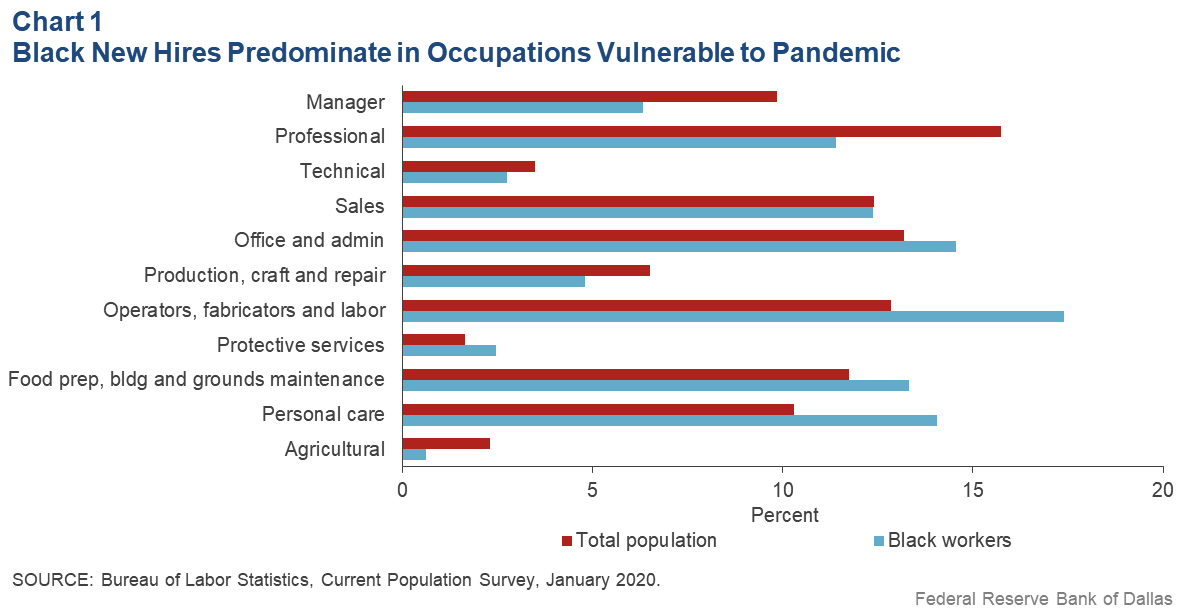

The Current Population Survey in January 2020 provides another perspective on employment. It can be used to identify “new hires,” people who transitioned from nonemployment to employment since January 2018 (Chart 1).

Responses from survey participants who remained in one place—there was no relocation—are viewed at 12-month intervals. The series shows blacks overrepresented among new hires relative to the overall U.S. working population.

The data indicate individuals in occupations such as food preparation, personal care, operators, fabricators and sales—representing 57.1 percent of new black hires—may be at particular risk because of an inability to telecommute. Additionally, underrepresentation of black hires in managerial and professional roles—18 percent compared with 26 percent for the overall population—indicates another vulnerability.

Thus, the current economic situation may offer a test of the last hired, first fired phenomenon.

Notes

- “Last Hired, First Fired: How the Great Depression Affected African Americans,” by Christopher Klein, History Channel website, April 18, 2018.

- “African Americans Face Systematic Obstacles to Getting Good Jobs,” by Christian E. Weller, Center for American Progress, Dec. 5, 2019.

- “Working from Home During a Pandemic: It’s Not for Everyone,” by Yichen Su, Dallas Fed Economics (blog), April 7, 2020.

About the Authors

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: https://www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2020/swe2002.