COVID-19 slammed into Texas, leaving long-lasting impacts

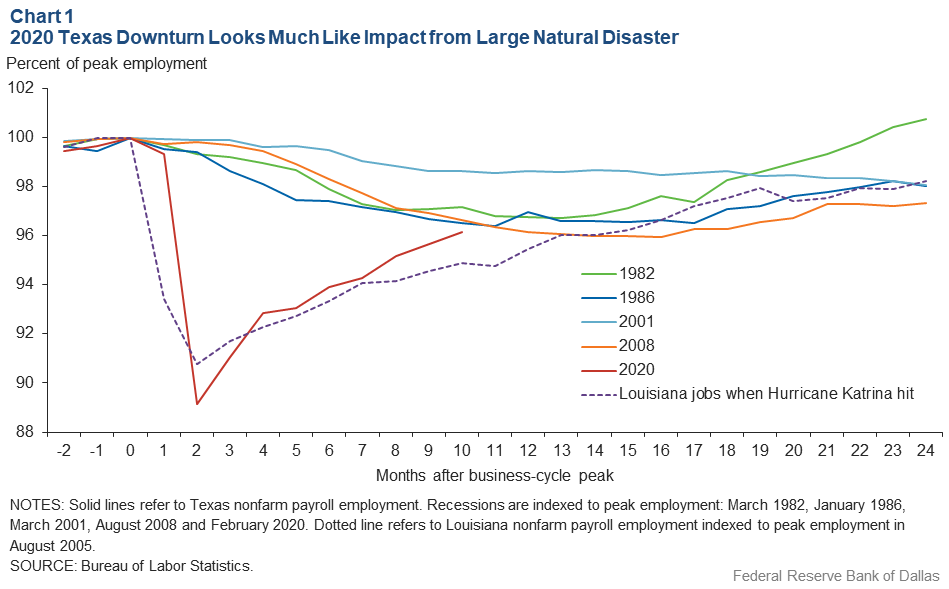

The economic downturn that began with the arrival of COVID-19 in March 2020 has greater resemblance to a natural disaster than a typical recession.

Most recessions begin with slowing growth that transitions into declining jobs and output. At the time, the process may appear so gradual that analysts often miss it until many months later.

By comparison, when a hurricane occurs—for example, Hurricane Katrina striking Louisiana in 2005—the economy suddenly halts, and jobs and output fall sharply. A quick return to growth follows just a couple months later, although a full recovery can take a year or more.

The pattern of job growth in Texas at the beginning of the pandemic resembles that of Louisiana following Katrina rather than past Texas recessions (Chart 1). The speed with which the state achieves prepandemic levels of output and jobs will depend on how quickly COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations decline and the long-lasting structural changes left behind.

Expecting a Slow Return

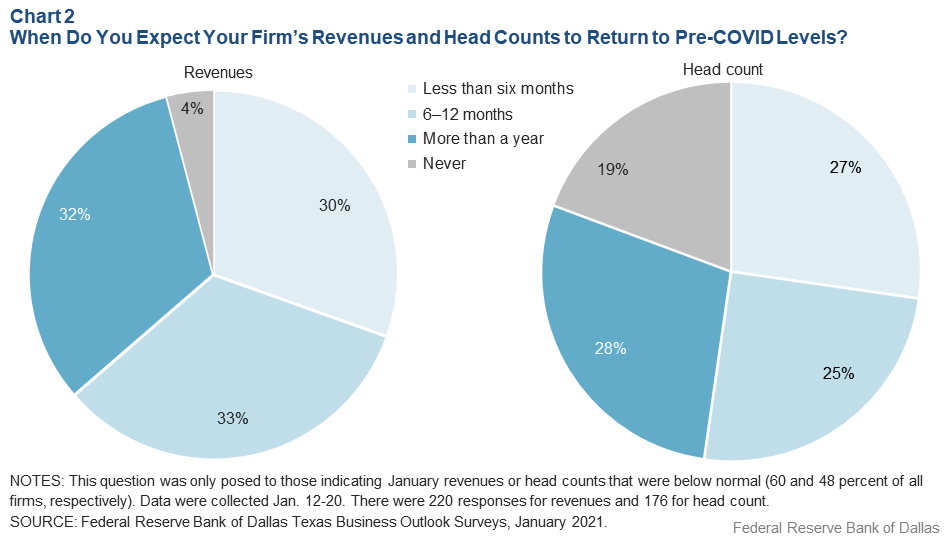

The pandemic fundamentally disrupted Texas business. Despite the economic recovery that began in May 2020, roughly 60 percent of firms in the Dallas Fed Texas Business Outlook Surveys (TBOS) reported that their January 2021 revenues remained below normal. When these responding executives were asked when they expected a return to pre-COVID-19 levels, 30 percent said within six months, and 63 percent said within a year (Chart 2). The vast majority—96 percent—anticipate full recovery, though nearly one third said it will take more than 12 months.

Restoring normal employment may take longer than reviving revenues. Among the 48 percent of firms reporting January 2021 head counts below prepandemic levels, nearly 20 percent said they do not expect them to ever return to pre-COVID-19 numbers. These businesses point to increased efficiency and productivity or streamlining due to technology adoption. Several companies said that they were overstaffed leading up to the pandemic.

These pandemic-spurred productivity improvements allow firms to generate more revenue per employee going forward. This wouldn’t be uncommon, as aggregate productivity tends to rise during economic downturns. A National Bureau of Economic Research study found that output per worker rose by more than 5 percent during the Great Recession.[1]

In the long run, productivity gains are a main source in a country’s standard of living. They spur both strong output growth and full employment.

However, in the short run, they can lead to slower job growth, particularly if there is a mismatch between the skills demanded by the new jobs and the skills of unemployed workers.

For example, the large number of workers displaced from the leisure and hospitality sector likely won’t readily transition to growing sectors such as information technology and financial services. They may more easily find employment related to e-commerce, such as in warehousing and parcel delivery services.

Long-Term Pandemic Impacts

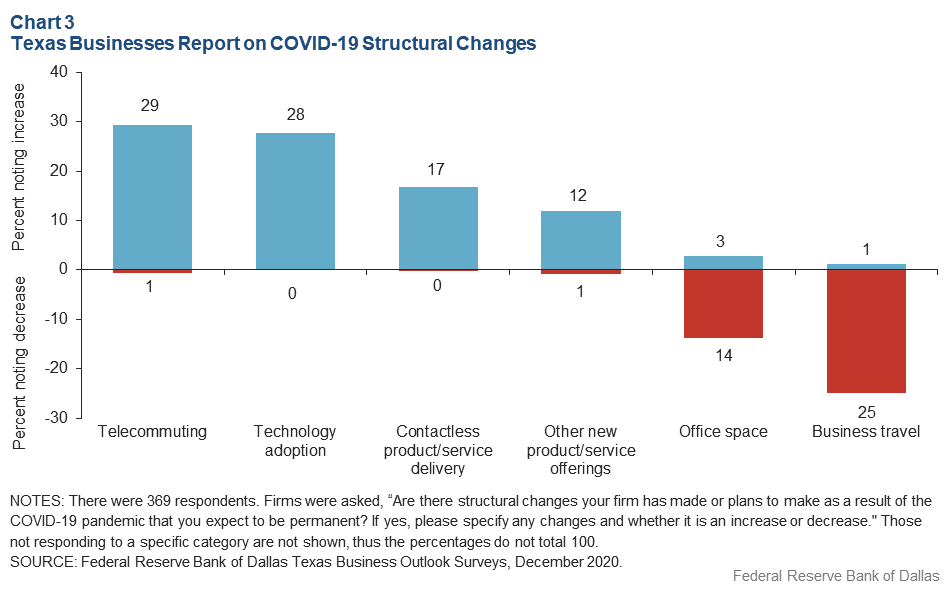

TBOS respondents reported at year-end 2020 whether they expected the structural changes instituted because of the pandemic to be permanent. Nearly 30 percent anticipated a permanent increase in telecommuting and technology adoption relative to pre-COVID-19 levels (Chart 3).

A quarter of firms expected a permanent reduction in business travel, and 14 percent said they likely won’t need as much office space.

These structural shifts portend changes in where people desire to live and work and also affect commuting. The impacts will affect business travel and the oil and gas sector.

More Remote Work Likely

During the pandemic, the dynamics of high-density mostly urban living changed—the potential of virus spread increased costs, while the benefits of leisure opportunities such as restaurants and entertainment fell. This, along with historically low interest rates, likely prompted a significant shift in Texas from city centers to suburban regions and larger homes.[2]

Moreover, the desire to work from home increased sharply due to early government “stay at home” orders and a fear of viral spread. During the initial outbreak, the average share of employees working remotely increased by 26.7 percentage points to more than a third of all workers (Table 1).

Table 1: Share of Work-from-Home Employees to Remain Elevated

| Average (percent) |

||

| Pre-COVID-19 | 8.3 | |

| Current | 35.0 | |

| Post-COVID-19 | 20.6 | |

| NOTES: Respondents were asked, “What share of your employees were working remotely in February 2020 (pre-COVID-19), and what share are currently (August 2020) working remotely? What share do you expect to work remotely after the pandemic ends?” There were 390 responses. Data were collected Aug. 18–26, 2020. SOURCE: Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Texas Business Outlook Surveys, August 2020. |

||

With numerous telecommuting platforms available to facilitate remote job activity, collaboration and even large-scale business transactions, work-from-home efficiency surprised many in a variety of industries.

The success of remote work likely will reduce demand for office space over the next few years from what it would have been absent COVID-19. TBOS contacts indicated that on average, they expect about 21 percent of their employees to continue working from home after the pandemic.

Office vacancy rates have increased across the state’s major metro areas. The fourth quarter 2020 office vacancy rate reached 23.4 percent in Dallas–Fort Worth and 22.3 percent in Houston, surpassing Great Recession peaks.[3]

With fewer workers commuting to urban centers, restaurants and retail in those areas may experience a slower recovery, and demand for gasoline (and thus, oil) will increase more slowly than would otherwise be the case following a downturn.

Still Moving to Texas

Some recent studies have found the pandemic not only resulted in some movement to the suburbs but may also have increased the desire of people to live in less-dense and more-inexpensive cities nationally, which would benefit states such as Texas.[4]

Data on population growth, U-Haul rental truck movements and a national builders survey all suggest that net inmigration into Texas from other states remained high last year.

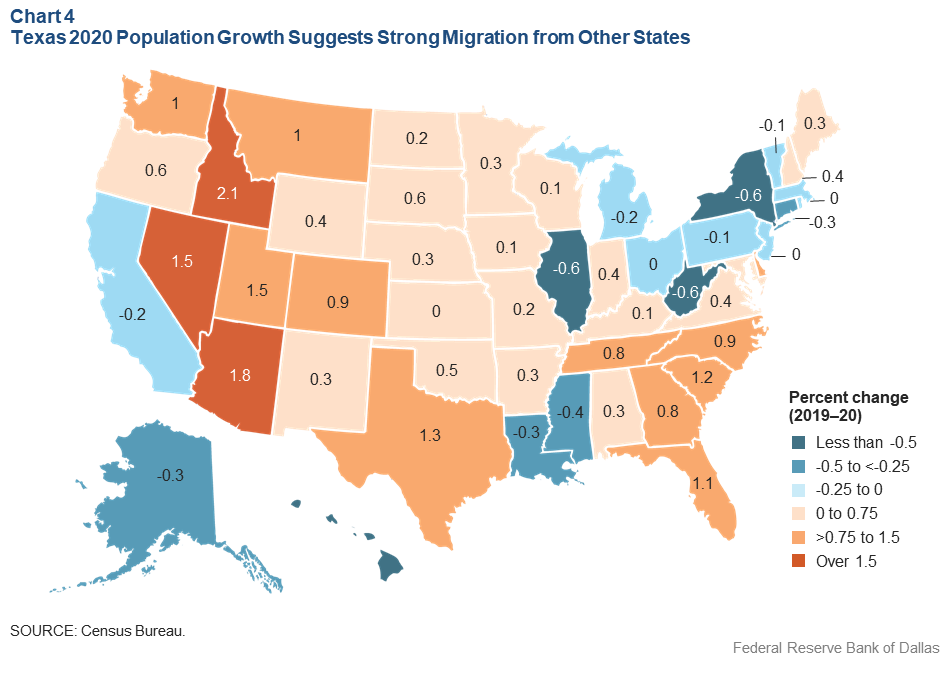

Texas’ population increased 1.3 percent in 2020—about the same pace as in 2019 and the fastest rate of growth of the 10 largest states (Chart 4). While a breakdown of the sources of the increase is not yet available, average growth rates of births, deaths and international migration to the state over the past five years provide an indicator.

These estimates along with census data imply that Texas net domestic migration increased by about 20 percent last year—to around 151,700.

The strength in net domestic migration to Texas is supported by data from U-Haul, which measures movements of one-way moving truck rentals. Last year, Texas ranked second in net trucks coming into the state—behind only Tennessee and ahead of Florida.

Interestingly, the top three states for net positive moves were three of only nine states that do not have a state income tax.[5] California was at the bottom of the list as the state with the greatest net outflow of moving trucks.

Also supporting strong net domestic migration, a Zonda research survey of builders in November 2020 found that 60 percent of 45 builders with operations in Texas said that out-of-market/out-of-state home purchases had increased in Texas, while 4.4 percent said they had decreased.[6]

Six out of the 10 builders that posted comments mentioned people moving from California or the West Coast, with one citing a “huge influx from California still continuing.”

Firms recently announcing relocation of major operations or headquarters to the state included Tesla, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Oracle and CBRE.

Business Travel Impacts

Telecommunications technology, and in particular web conferencing, has gained new prominence—digital platforms such as Skype, Lifesize, Zoom, GoToMeeting and Cisco WebEx. While their development generally began in the mid-1990s, their use accelerated during the pandemic.

As employees shifted to working from home, they were forced to learn about these platforms and began appreciating their ease of use. Many internal and external conferences were converted from in-person events to digital, and business travel declined dramatically in 2020. How fast and how far business travel rebounds remains subject to debate, though experts in the field predict a slow recovery to prepandemic levels.

In a survey of meeting planners in January 2021, only 22 percent anticipated resuming face-to-face meetings in the first half of the year, with 25 percent seeing a third-quarter resumption, 27 percent anticipating a return at year-end and 18 percent suggesting a resumption in 2022.[7] When asked about what percentage of 2019 events activity they foresee coming back, just 7 percent reported returning to 2019 levels this year, 32 percent by 2022 and 71 percent by 2023.

If meetings and conferences are slow to return, then industries relying on business travel, such as airlines, hotels, restaurants, retail and convention centers will feel the effects. Nationally, hotel occupancy averaged just 44 percent last year, and revenue per available room was down 48 percent from 2019, according to hospitality analytics firm STR, a unit of CoStar Group Inc.[8]

Luxury hotels performed far worse, with 21 percent occupancy in December 2020 versus 68 percent in 2019, while economy hotel occupancy was 45 percent in December compared with 48 percent in December 2019. STR forecasts that overall room demand will rebound to 2019 levels by 2023, and it won’t be until 2024 before revenue per available room fully recovers.

How will reduced business travel affect the jobs recovery in Texas? While detailed data on business travel are difficult to obtain, broader measures of the sector’s size provide insight regarding the potential outline of a rebound.

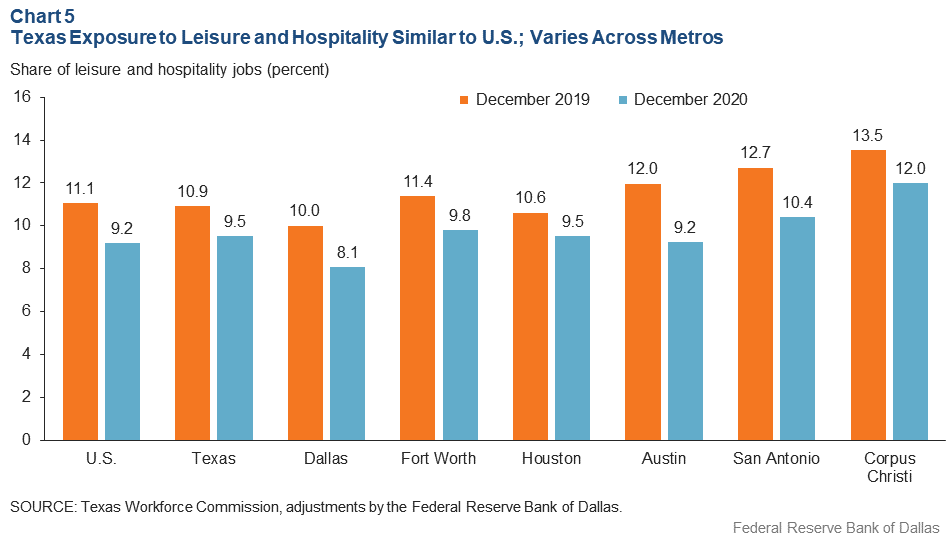

About 11 percent of jobs in Texas and the U.S. were in leisure and hospitality in 2019, though the figure was much higher in metros such as San Antonio and Corpus Christi (Chart 5). Given the sector’s size, especially in certain areas, its slow return may depress job growth this year, even as other sectors and certain portions of the industry—such as leisure travel and local spending on restaurants—grow strongly.

Oil and Gas Sector Impact

Texas accounted for 41 percent of U.S. oil production and 25 percent of U.S. natural gas production in 2019. With the rise in working remotely and the declines in air travel and leisure and hospitality activity, worldwide fuel demand plummeted in the first half of 2020.

Gasoline consumption fell by nearly half and jet fuel by 70 percent nationally.[9] The reduced demand for oil products played a major role in a large decline in the monthly average price of West Texas Intermediate Crude (WTI)—from $59.88 per barrel in December 2019 to $16.55 in April 2020. Prices subsequently recovered to an average of $59.05 per barrel by February 2021.

Although contacts in the first-quarter Dallas Fed Energy Survey reported increased activity and an improved outlook, commuter and business travel won’t likely return to pre-COVID-19 levels over the next several years.

Survey respondents expected the price of WTI to be $61 in fourth quarter 2021, slightly above the average breakeven price the survey reported in first quarter 2021. Despite higher oil prices, slightly over half—53 percent— of executives expect their head count to remain unchanged from December 2020 to December 2021.

Vaccinations Remain Key

Assuming there is COVID-19 vaccine efficacy and a high percentage of the population is vaccinated or immune by the third quarter, the Texas economy should grow strongly in the second half of 2021.

Structural changes and frictions in the labor market might impact the pace of job gains and a return to pre-COVID-19 employment levels in Texas. Shifting demand toward less dense, lower cost of living areas, such as those in Texas, should support economic growth.

Overall, the changes suggest that Texas will continue to see stronger job growth than the national average and employment will return to pre-COVID- 19 levels before the end of the year. However, jobs will still be below the trend level suggested before COVID-19. Jobs in Texas will likely grow a strong 6.0 percent this year, according to the Dallas Fed Texas Employment Forecast.[10]

Households that have pent up demand and built up savings should return to restaurants and vacation destinations and even some high-contact events such as concerts and sporting events. At a growth rate of 6.0 percent, however, jobs in December 2021 would still be about 0.9 percent (116,000 jobs) above the peak level reached in February 2020, but below the previous trend by 2.7 percent (359,000 jobs).

Notes

- “Making Do with Less: Working Harder During Recessions,” by Edward P. Lazear, Kathryn L. Shaw and Christopher Stanton, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper no. 19328, August 2013.

- “COVID-19 Fuels Sudden, Surging Demand for Suburban Housing,” by Laila Assanie and Yichen Su, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Fourth Quarter 2020.

- From CBRE Research.

- “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Demand for Density: Evidence from the U.S. Housing Market,” by Sitian Liu and Yichen Su, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Working Paper no. 2024, revised October 2020; “Emerging Trends in Real Estate 2021,” Urban Land Institute and PwC, accessed Feb. 22, 2021.

- Tennessee and New Hampshire are among the nine states, although they collect taxes on interest and dividend income.

- Survey from Zonda advisory of homebuilders operating in Texas and their assessment of the impact of COVID-19. Results presented Jan. 27, 2021.

- i-Meet Planner Confidence Index, “2021 Planner Confidence Index–Phase 3,” a weekly survey of trends and evolving opinions of meeting professionals.

- “STR, TE Slightly Downgrade Latest U.S. Hotel Forecast,” STR Global, Jan. 26, 2021.

- “Lower U.S. Crude Oil Production Decreases Output, Raises Price of Natural Gas,” by Jesse Thompson and Camila Holm, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Fourth Quarter 2020.

- “Texas Employment Forecast,” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, March 26, 2021

About the Authors

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to Banco de México, the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2021/swe2101.