Pandemic pushes Texas minority unemployment beyond highs reached during Great Recession

Recessions are hardest on minorities; the COVID-19 downturn is no different in that regard.[1] Texas is a majority minority state—more than half of Texas’ population is Hispanic or Black—and the consequences are far-reaching if those groups lag behind economically.

Once the pandemic hit, the state lost 1.4 million jobs from February to April 2020, and the unemployment rate shot up to 12.9 percent. The recovery that began in May has been slow, hampered by the repeated resurgence of the virus. Texas’ unemployment rate of 6.9 percent at year-end was well above what it was before COVID-19 hit (3.7 percent), and more than 625,000 jobs were lost.

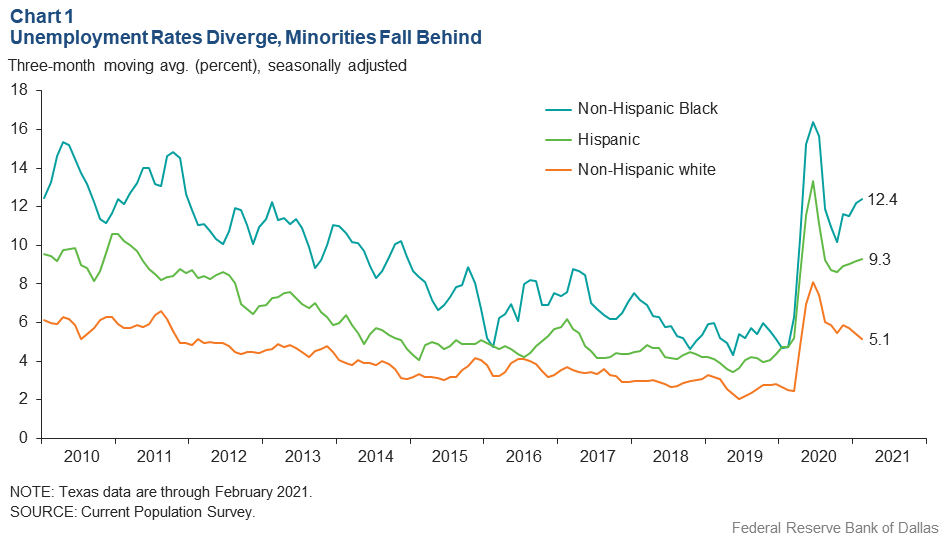

One year into the pandemic, Texas’ labor market disparities are glaring (Chart 1). About 9.3 percent of Hispanic workers were unemployed in February, 4.6 percentage points above prior-year levels. Roughly 12.4 percent of non-Hispanic Black workers were unemployed, 7.6 percentage points higher.

Unemployment among Black workers in Texas was more than twice that for non-Hispanic white workers, whose jobless rate was 5.1 percent in February, 2.6 percentage points above February 2020.

Early in the pandemic, as the government imposed lockdowns and only essential businesses remained open, the disparate impact on workers became clear. White-collar workers operating from home largely escaped job cuts, while blue-collar workers in essential businesses such as grocery stores remained on payrolls but were exposed to the risk of COVID-19 infection.[2]

Jobs vanished for restaurant, bar and hotel workers and for businesses linked to arts and recreation, transportation and personal care.

Minorities are disproportionately employed in many of these generally lower-paying, face-to-face service industries, partly because they have less education on average than non-Hispanic white workers. These workers also tend to be younger. And within all groups, women have been especially affected because they are disproportionately employed in the service sector and frequently must deal with parental duties.

Great Recession Comparison

At the height of the pandemic recession last spring, all groups’ unemployment rates surpassed their Great Recession peaks. Black unemployment reached 16.4 percent; Hispanic joblessness hit 13.3 percent. However, most layoffs were temporary, and minority unemployment fell through the summer and fall as workers were called back. That trend reversed course in the fourth quarter when a second COVID-19 wave took hold, even as white unemployment continued to decline.

Workers dropping out of the labor force poses another pandemic-era concern.[3] Black labor force participation fell dramatically in first quarter 2020 with the onset of COVID-19; non-Hispanic white worker declines occurred largely in the second quarter, a period that included stay-at-home orders. By comparison, Hispanic labor force participation was little changed during the year.

Through February 2021, overall labor force participation rates remained below prepandemic levels.

In addition to direct stimulus payments, unemployed workers in the pandemic have received supplemental unemployment benefits and extended unemployment benefits. The benefits have also gone to the self-employed and other groups typically ineligible for unemployment insurance.

The initial provision of $600 per week in supplemental benefits boosted earnings to such a degree that many beneficiaries earned more while unemployed than while working. The payments expired in the fall and were last renewed in March to run into early September at $300 per week.

Thus, despite record-high unemployment rates, many who lost jobs during the pandemic could make ends meet because of governmental support. After federal assistance ends, a large number of Texans—many of them minorities—will need job opportunities if they are to get back to work.

Notes

- “Black Workers at Risk for 'Last Hired, First Fired,'” by Aquil Jones and Joseph Tracy, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Second Quarter, 2020.

- “Commuting Patterns During COVID-19 Endure; Minorities Less Likely to Work from Home,” by Alexander Bick, Adam Blandin and Karel Mertens, Dallas Fed Economics, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Sept. 1, 2020.

- “Pandemic Disproportionately Affects Women, Minority Labor Force Participation,” by Tyler Atkinson and Alex Richter, Dallas Fed Economics, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Nov. 10, 2020.

About the Authors

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: https://www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2021/swe2101.