Students cut college during pandemic; their return is uncertain

Colleges and universities abruptly emptied. Everything, it seemed, was online.

As COVID-19 spread across the U.S. in first quarter 2020, followed by waves of its variants, virtual instruction took hold and rolled on through the 2020–21 and 2021–22 academic years. Worrisome infection rates not only limited in-person learning, they also curtailed most campus activities—sports and entertainment included. The student experience was turned on its head in an era of evolving vaccine requirements and mask wearing.

Prospective college students faced another set of challenges. Successive classes of high school seniors lacked academic preparation for higher education, let alone assistance navigating the college application process, while pandemic-related financial shocks put college further out of reach for some.

Two years into the pandemic, as the virus’ impact recedes, the results have become clear: steeply declining college enrollment in Texas and across the country. Particularly noteworthy, normally accessible community colleges have experienced the greatest drop-off. The vanishing students portend a possibly less-educated and less-versatile future workforce.

Enrollment Decline Quickens

Enrollment in fall 2021 for postsecondary education (colleges and universities) nationally declined 5.1 percent from prior-year levels, the National Student Clearinghouse found (Table 1).[1] Although U.S. college enrollment was trending lower before the pandemic, the subsequent drop was much more pronounced.

Table 1: College Enrollment Declined During Pandemic

| Fall 2019 | Fall 2021 | Fall 2021 % change from fall 2019 |

|

| U.S. | |||

| Public 2-yr | 5,368,470 | 4,662,364 | -13.2 |

| First-time freshmen (age 24 and younger) | 759,649 | 626,017 | -17.6 |

| Public 4-yr | 7,989,984 | 7,767,617 | -2.8 |

| First-time freshmen (age 24 and younger) | 927,723 | 878,208 | -5.3 |

| Private nonprofit 4-yr | 3,842,930 | 3,776,285 | -1.7 |

| First-time freshmen (age 24 and younger) | 399,426 | 385,304 | -3.5 |

| Total | 18,239,874 | 17,302,364 | -5.1 |

| First-time freshmen (age 24 and younger) | 2,143,023 | 1,955,529 | -8.7 |

| Texas | |||

| Public 2-yr | 647,127 | 607,763 | -6.1 |

| Public 4-yr | 704,194 | 668,881 | -5.0 |

| Private nonprofit 4-yr | 125,156 | 121,131 | -3.2 |

| Total | 1,490,953 | 1,428,231 | -4.2 |

| NOTES: Enrollment is for both undergraduate and graduate programs. First-time freshmen are undergraduate students entering college in the fall term for the first time. Total includes private for-profit, four-year institutions. SOURCES: “Overview: Fall 2021 Enrollment Estimates,” National Student Clearinghouse; authors’ calculations. |

|||

Texas’ population has grown faster than the nation. Despite this growing potential student pool, the state’s total college enrollment fell 4.2 percent from 2019 to 2021, smaller than the national drop.

Community colleges in the state, like those in the nation, were particularly affected, with enrollment down 6.1 percent from fall 2019 levels. Meanwhile, Texas’ four-year universities reported larger enrollment declines than their counterparts nationally. Before the pandemic, Texas enrollment was increasing in contrast to declines nationally.[2]

The pandemic recession—albeit a brief two months—differed from previous downturns with high unemployment. During those episodes, people typically returned to school to build skills. This outcome, in contrast, resulted in lower postsecondary numbers. Public four-year enrollment decreased 2.8 percent nationally, while community colleges experienced a 13.2 percent decline over the pandemic’s initial two years.

Undergraduate students entering college for the first time appear to have been more affected than other students. Enrollment among first-time freshmen, age 24 years and younger, declined by a larger percentage across all types of institutions, suggesting that the pandemic disproportionally disrupted college education for young adults.

Why Not in School?

The Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Surveys provide real-time insight into factors affecting postsecondary enrollment. The survey queries respondents online regarding economic experiences during the pandemic.

The survey asked whether adults in the respondent household had changed their college plans—if they had any—and the reasons for the changes. Data from survey periods (Sept. 16–28, 2020, and Sept. 15–27, 2021, weeks 15 and 38, respectively) highlight changes in fall college enrollment plans.[3] Approximately 73 percent of all respondents who had college plans reported that they had changed them as of the fall term 2020; about one-third in Texas and nationwide reported canceling all plans.[4] Not all plan changes were cancellations. Many students took fewer (or more) classes, had classes in a different format or at a different institution or took classes for different kinds of certificates or degrees.

There were far fewer respondents to the fall 2021 Pulse survey, and many skipped the college plan questions. Still, the share reporting that they canceled college plans was about half that of the prior year—about 15 percent—in Texas and the U.S.[5]

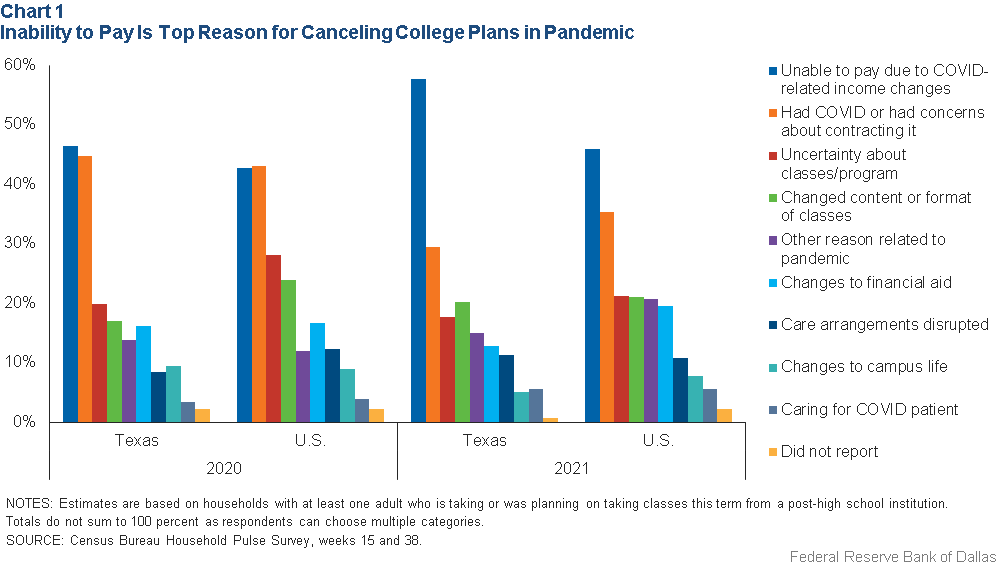

The survey asked what prompted the changed college plans. Looking at those who opted not to enroll, the top reason was an inability to pay for school due to a pandemic-related income change (Chart 1).

COVID-19 illness or fear of catching the virus was the second-most cited reason for canceling college plans. Uncertainty about classes or programs was the third-most frequent reason, while changes in class content or format was the fourth-most noted reason for skipping college.

Texans were less likely to view the uncertainty, content or format changes as a negative factor, perhaps because the state’s colleges returned to in-person classes sooner than those elsewhere.

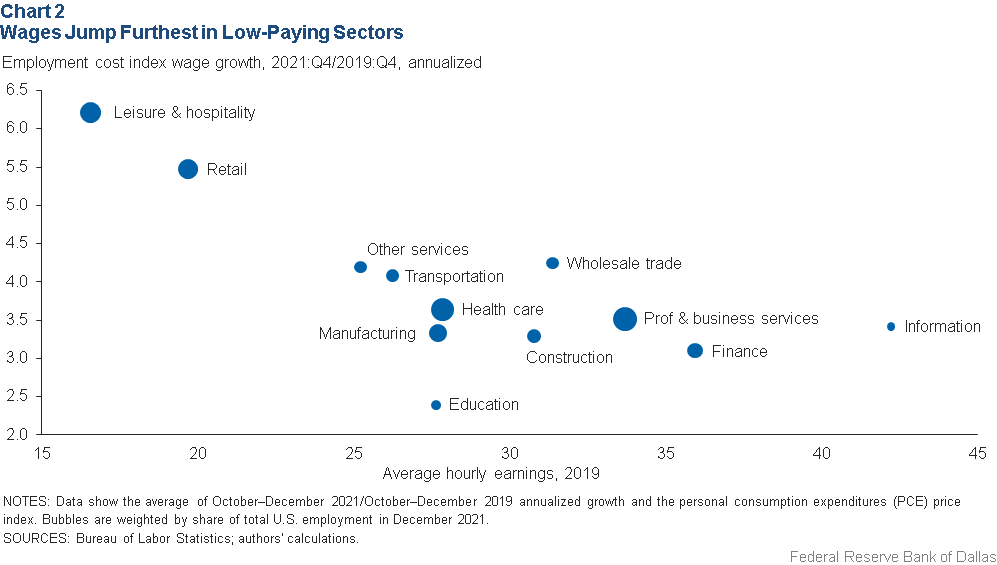

What about leaving school for work opportunities? In the months after the pandemic’s onset in spring 2020, labor markets quickly rebounded and demand for workers outpaced supply, particularly among lower-skill positions, for which pay quickly rose (Chart 2).

The survey did not directly ask about labor market opportunities, but for some potential students, plentiful employment openings and higher wages for low-skill jobs might have made work more appealing than school. Among all age groups, employment rates in the pandemic recovered first for 16–19-year-olds. Those vulnerable to health risks or whose parents needed help with care for younger siblings though, may have opted to stay out of school and the job market.[6]

Demographic Factors

The Pulse survey also sheds light on the role of demographics during the period. Applying regression analysis to the national data suggests that—all else equal—cancellation of education plans is positively correlated with being Black or Hispanic. It is also positively correlated with lower income status. This is consistent with the pandemic’s greater impact on community college enrollment, as these demographics comprise a larger share of students at two-year campuses.

Texas data, though less robust, yield a similar result. However, there is no correlation with being Hispanic.

Impact Among Men

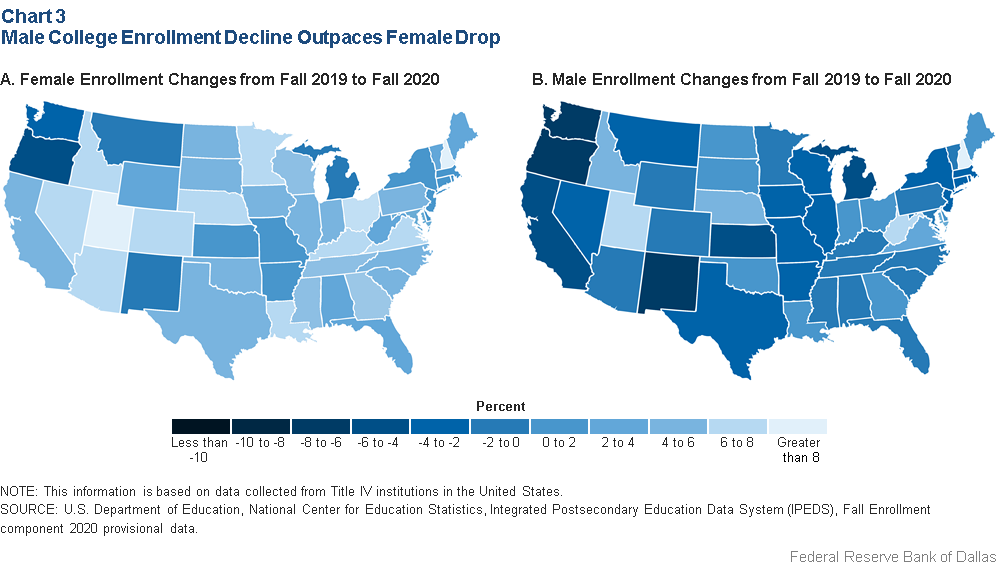

Men’s college enrollment fell about twice as much as that of women during the pandemic (Table 2). Community college enrollment fell 16 percent for men compared with 11 percent among women. Men also drove the overall enrollment drop at four-year institutions.[7] This is consistent with a long-run trend of declining male college attendance.

Table 2: Men Far More Likely Than Women to Skip College in Pandemic

| Fall 2019 | Fall 2021 | Fall 2021 % change from fall 2019 |

||

| Public 2-yr | Men | 2,256,354 | 1,891,359 | -16.2% |

| Women | 3,112,115 | 2,771,005 | -11.0% | |

| Public 4-yr | Men | 3,477,314 | 3,296,535 | -5.2% |

| Women | 4,512,670 | 4,471,082 | -0.9% | |

| Private nonprofit 4-yr | Men | 1,535,530 | 1,485,664 | -3.2% |

| Women | 2,307,400 | 2,290,620 | -0.7% | |

| Total | Men | 7,606,756 | 7,059,178 | -7.2% |

| Women | 10,633,118 | 10,243,187 | -3.7% | |

| NOTE: Enrollment for both undergraduate and graduate programs are included. SOURCE: "Overview: Fall 2021 Enrollment Estimates," National Student Clearinghouse. |

||||

Additionally, the decline is indicative of labor market opportunities that appeared following the onset of the pandemic. Job retention and creation was tilted toward male-dominated occupations, especially as women bore much of the burden of caring for children unable to attend in-person classes or daycare.[8]

Longer term, men have fallen behind women in college enrollment as access to higher education and the career path for women improved.[9] The share of men attending colleges and universities fell to 40.9 percent in fall 2020, from 42.3 percent in 2019 and 43.7 percent in 2015.[10]

State-level enrollment data by gender are available only until fall 2020 (Chart 3). The male decline accelerated for almost all states from fall 2019 to fall 2020. In Texas, undergraduate enrollment fell 6.4 percent for men and 1.1 percent for women.

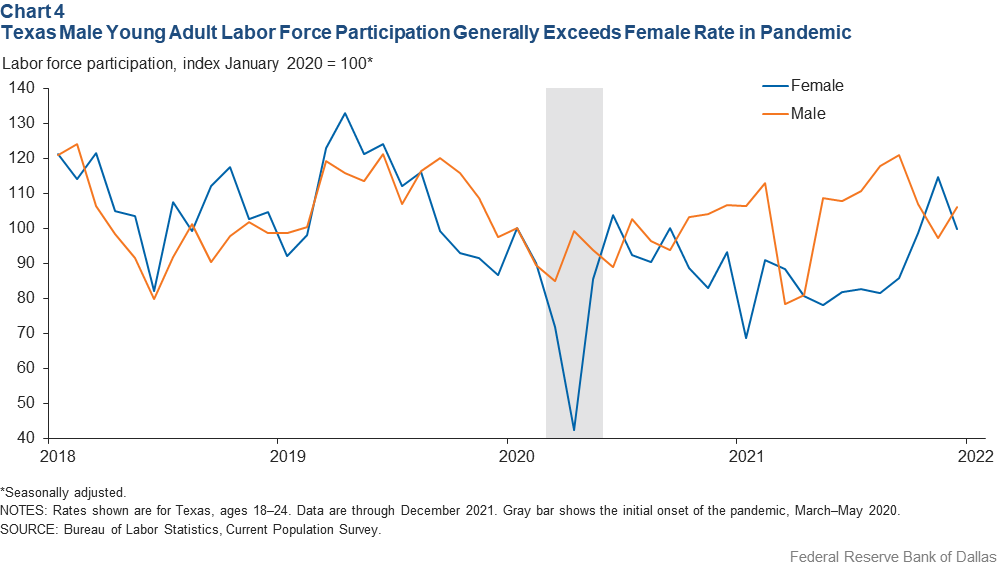

Meanwhile, the labor force participation rate for Texas men ages 18 to 24 generally exceeded that of women during the pandemic (Chart 4).[11] To the degree that labor shortages helped prompt some prospective students to not pursue a college education, they may motivate more men than women.

Loan Payment Relief

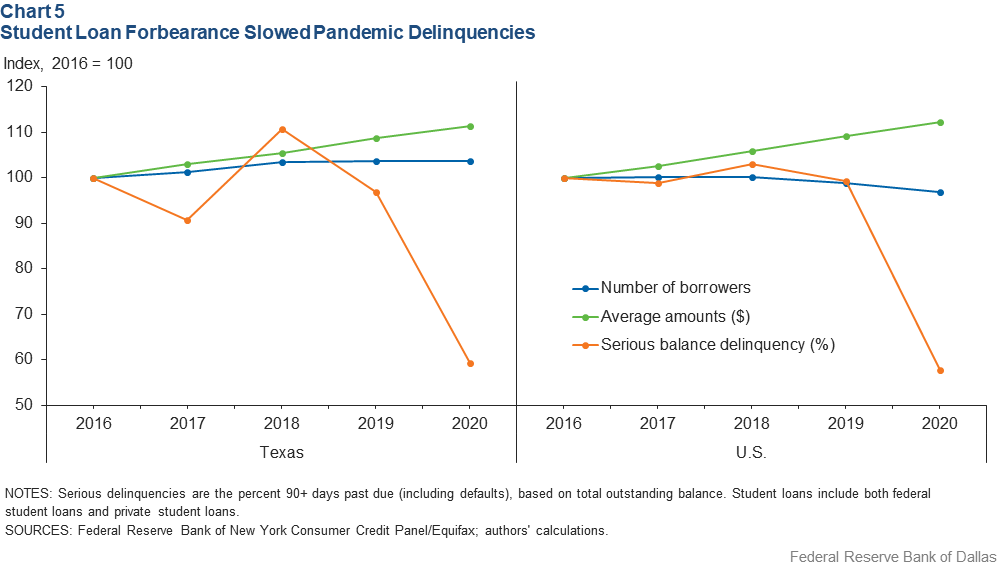

While some students canceled college plans due to an inability to pay, aid to students and institutions actually increased during the pandemic. Qualified federal student loan payments were suspended at a zero-interest rate beginning in March 2020 under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act and Department of Education administrative acts.[12]

Collections also stopped on defaulted loans.[13] Thus, the unpaid outstanding student loan balance grew, totaling $1.6 trillion in third quarter 2021, despite a decrease in borrowing.[14] Borrowers with large loan balances or with obligations in distress have benefited most from the pause in payments. Delinquencies will likely reappear in credit reports when repayment obligation resumes in May 2022.[15]

Student loan originations declined in response to the falling college enrollment. The number of new student loan borrowers fell in the past two academic years in Texas and nationally, according to calculations based on New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax data.[16]

The total number of student loan borrowers with outstanding balances in Texas was little changed during the first year of the pandemic (Chart 5).

Disrupted Education

Enrollment for postsecondary education has declined broadly during the pandemic. A particularly large drop in community college enrollment reflects the sensitivity to pandemic disruptions for lower-income and minority students, who represent a large share of students at these schools.

Community colleges serve as a relatively affordable entry to general education and skills training, with graduates able to transfer to traditional universities to continue their education. As a result, the lower enrollment may lead to a less-prepared labor force that lacks education and skills for the workplace and produces fewer students for traditional four-year institutions.

The gender gap in college enrollment also widened during the pandemic. Among women, likely burdened by family care responsibilities during the pandemic, community college enrollment declined.

However, the enrollment decline for men was much larger than for women, reaffirming a long-term trend of lower higher-education enrollment for men.

More young men joined the workforce, likely because of higher wages offered for lower-skill positions. Skipping college can, however, reduce lifelong earnings and lead to fewer job opportunities in the long term.

Notes

- “Current Term Enrollment Estimates, Fall 2021,” the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, Jan. 13, 2022. The Clearinghouse data account for 97 percent of all enrollments at Title IV, degree-granting institutions in the U.S.

- Texas community college enrollment rose 2.1 percent in 2021 from the sharp decline in the pandemic’s first year. Public and private nonprofit four-year enrollment increased slightly in fall 2020 but fell in fall 2021.

- In the September 2020 survey, about 19.6 percent of respondents had adults in the households with postsecondary education plans. In the September 2021 period, that share dropped to 16.2 percent. The survey’s response rate declined over the two periods, which may imply substantial nonresponse biases.

- The percentages are higher than enrollment estimates from the National Student Clearinghouse or from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System because not all with a college plan applied to college or got admitted. The Pulse responses are self-reported.

- Survey questions are specific to the pandemic, so there are no comparable prior data about plan changes.

- “Skipping School: Enrollment Numbers Down for Students Ages 16–24 During Pandemic,” by Anna Crockett and Jason Saving, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Dallas Fed Communities, Jan. 24, 2022. “Employment Numbers Suggest Young People Face Barriers in Recovery from Pandemic,” by Anna Crockett and Jason Saving, Federal Reserve Dallas Fed Communities, Dec. 9, 2021.

- Women’s enrollment declined at a similar rate as the prepandemic rate at public or private nonprofit four-year institutions. See the eighth column in Table 8 in “Overview: Fall 2021 Enrollment Estimates,” by the National Student Clearinghouse Center. The preliminary Texas enrollment data are not broken down by gender.

- “The She-Cession by the Numbers,” by Liz Elting, Forbes, Feb. 12, 2022,

- "The Homecoming of American College Women: The Reversal of the College Gender Gap," by Claudia Goldin, Lawrence F. Katz, and Ilyana Kuziemko, Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 20, no. 4, 2006, pp. 133–156. Developmental and behavioral differences are suggested.

- The National Student Clearinghouse includes only degree-granting institutions, while the National Center for Education Statistics data also cover nondegree-granting institutions. There are also reporting period differences between the two.

- The trend is noisy due to a small sample size.

- The U.S. Department of Education extended the payment pause to May 1, 2022. All federal loans qualify except for Perkins loans not held by the department,

- “The Early Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Consumer Credit,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Office of Research Special Issue Brief, August 2020. Loans not in default under this “administrative forbearance” include previously delinquent ones, which are considered current. Nonpayment has no negative impact on borrowers’ credit.

- “Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid 2021,” The College Board, accessed March 4, 2022. Student loans are one of the major sources of funds for postsecondary education. However, the percent of student loans as a share of the college costs have gradually declined from 40 percent to 30 percent, as grants become more available. Grants increased from 49 percent to 64 percent of total funds.

- "Student Loan Repayment During the Pandemic Forbearance," by Jacob Goss, Daniel Mangrum and Joelle Scally, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, March 22, 2022.

- The New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax is a nationally representative anonymous random sample from Equifax credit files. It tracks all consumers with a U.S. credit file residing in the same household from a random, anonymous sample of 5 percent of U.S. consumers with a credit file. Equifax data assets are used as a source but all calculations, findings and assertions are those of the authors.

About the Authors

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2022/swe2201.