Turbulent economy tests Texans who lack financial knowledge

Navigating personal finance has rarely been more challenging than today, as the world economy attempts to move past the COVID-19 pandemic and manage the fallout from the Russia–Ukraine war. The end of pandemic stimulus, rising inflation and interest rates, increasing rents and the pending resumption of student debt repayment obligations will test many households’ checkbook agility.

Making informed decisions about one’s income and expenses requires a degree of financial literacy—“the ability to use knowledge and skills to manage financial resources effectively for a lifetime of financial well-being.”[1]

Studies have shown that financial literacy improves household financial outcomes involving saving, investing and debt.[2] To provide an indicator of the extent of the public’s knowledge, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), a brokerage and exchange markets oversight organization, periodically surveys individuals across the country about their financial literacy.

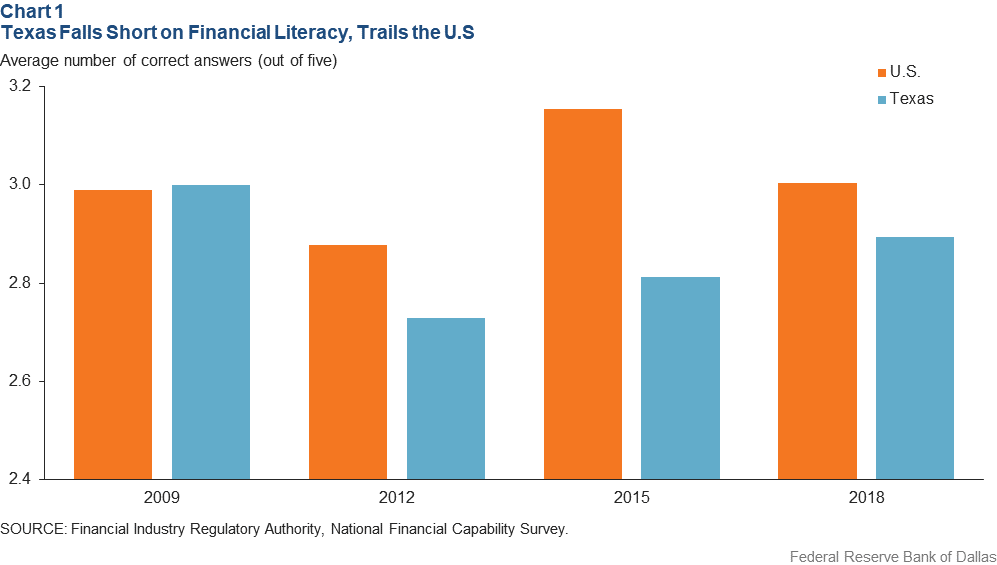

In FINRA’s most recent “National Financial Capability Study in 2018,” Texas’ performance ranked 43rd among the 50 states and District of Columbia. A five-question quiz that is part of the overall survey tests knowledge of bond prices and interest rates, mortgages, compound interest and portfolio diversification and provides a top-level assessment of financial literacy. While the survey tests overall financial literacy, its questions may be outside the usual experience of certain demographic groups who lack experience with financial instruments such as stocks and bonds.

The average Texas quiz score has improved little since 2012 when the state ranked 45th—a result detailed in Southwest Economy in 2016.[3] The 2018 quiz—which was taken nationwide by 25,000 adults—found that Texans have consistently trailed the nation in their ability to understand personal finance over the past decade (Chart 1).[4] Notably, the Texas–U.S. gap has shrunk over the past three surveys.

Teaching Financial Literacy

Texas lawmakers have recognized the importance of financial literacy, as well as the state’s lagging performance. As a result, they have passed measures twice in the past 15 years to address the subject in K-12 schools, though falling short of fully requiring and funding instruction.

In 2007, Texas mandated students have access to elective courses on personal finance and that required material be integrated into preexisting classes, “including instruction in methods for paying for college and other postsecondary education and training.”[5] Supporting coursework was added to the curriculum in 2016. The state has also supported annual events such as financial literacy month in April.

The 2021 Legislature revised social studies curriculum requirements for high school programs to provide students the option to complete one-half credit in personal financial literacy and economics as an alternative to one-half credit in just economics.

The law also requires that the Texas Education Agency, which oversees public primary and secondary education in the state, develop a list of free, publicly available materials for school district use in personal finance and economics classes. It also instructed the agency to seek private and public grant money in support of this curriculum. Notwithstanding the state’s efforts, Texas still falls short of the nation on financial literacy.

Financial Outcomes Suffer

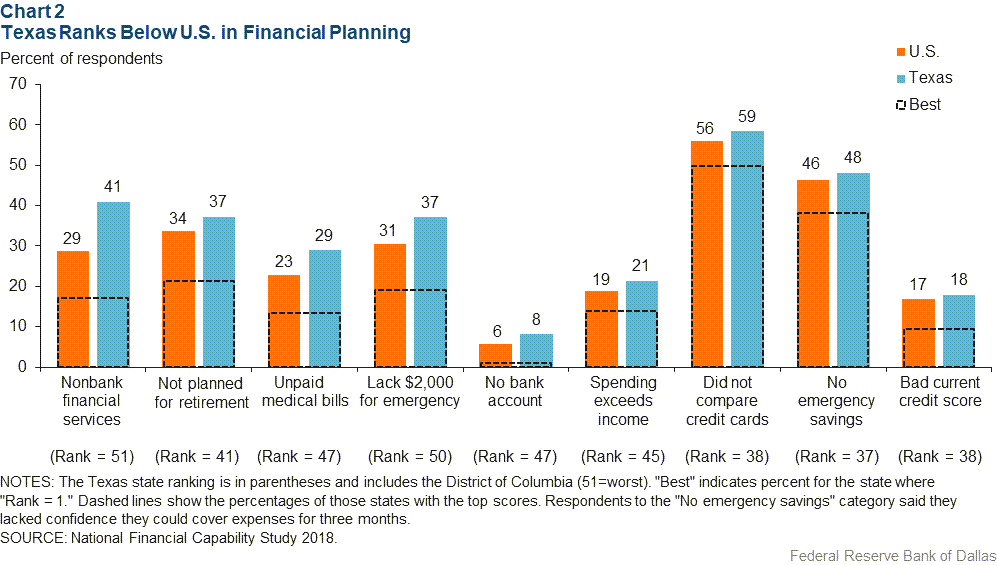

FINRA’s 2018 survey also gathered information on the personal finances and financial vulnerability of households. Texas’ low financial literacy rate is correlated with poor outcomes on such measures. For example, 8 percent of Texans don’t have bank accounts compared with 6 percent nationwide, and 41 percent use nonbank financial services, a far higher share than the 29 percent nationally (Chart 2).[6] Nonbank financial service companies include payday lenders and pawn shops, as well as much larger entities such as nonbank mortgage lenders.

FINRA also found that 48 percent of Texans had not set aside money for emergencies that would cover expenses for three months in case of sickness, job loss, economic downturn or other emergencies—ranking the state 37th in the nation.

Another indicator of financial health is retirement planning. In the survey, 37 percent of Texas participants said they lacked a retirement plan through a current or previous employer compared with 34 percent nationally.

In addition, 18 percent of Texas respondents in the 2018 FINRA survey reported that their current credit score was “bad” or “very bad”—putting the state in 38th place. Nationally, 17 percent of respondents similarly assessed their credit scores.

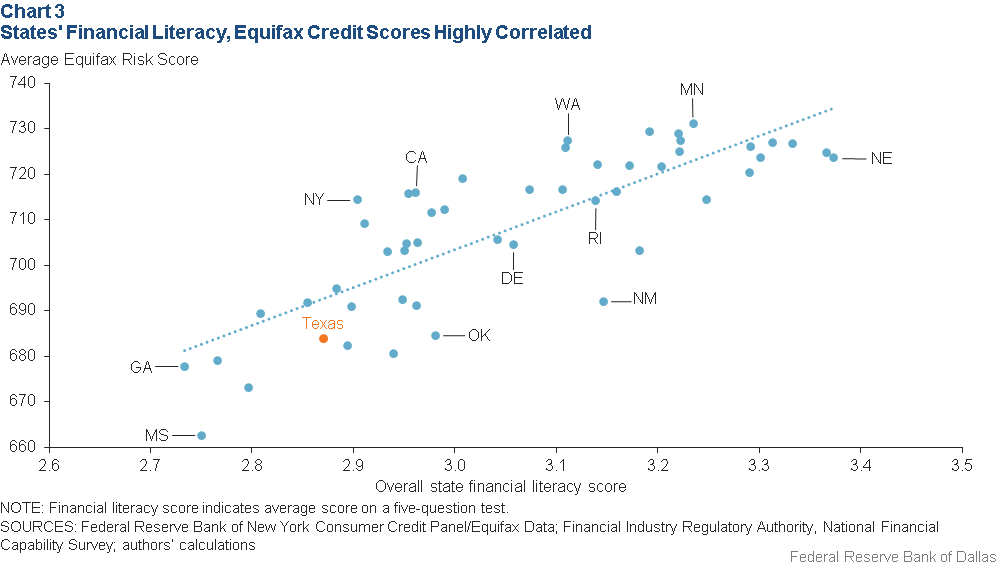

Equifax Risk Score data, available through the New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax, can be used to assess correlation between FINRA quiz scores and risk/credit scores at the state level.[7], [8] If the quiz questions are accurately gauging financial literacy among a representative sample of the state’s adults, then there should be a clear positive correlation with Equifax Risk Scores. Chart 3 indicates that states with lower FINRA quiz scores also have lower risk scores, on average.

However, consumers who don’t have credit relationships that would be the basis of credit reports tend to be overrepresented in states such as Texas, with large minority, low-income and immigrant populations.

High Debt Collections

Difficulty managing payments, whether on a car loan or a utility bill, can result in borrowers being subject to debt collection. An Urban Institute 2020 survey showed that 41 percent of Texas residents were subject to debt collection, the second highest in the country behind Louisiana.[9] By comparison, Minnesota had the fewest collections, 14 percent, followed by South Dakota at 16 percent.

One reason Texas ranks high in debt collection is due to medical debt referred to collection, placing the state 48th of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Only three states ranked worse than Texas: West Virginia, South Carolina and Louisiana.

Medical debt likely reflects Texas’ low level of health insurance coverage. The state has the highest share of uninsured working-age adults in the nation at 21 percent. This is a longstanding problem and may have slightly worsened when Texas opted out of the Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act.[10] According to one study, Medicaid expansion in Texas would have insured an additional 1.3 million residents.[11]

However, medical debt will become a less notable portion of consumer debt. The nation’s three largest credit reporting agencies plan to drop most medical debt from consumers’ credit profiles due to systemic reporting errors on credit reports.[12]

In the FINRA survey, 74 percent of Texas respondents said they have health insurance, the lowest percentage among the states and the District of Columbia.[13] A total of 29 percent of Texas respondents claimed they have unpaid bills from health care, the fifth highest in the survey group. Notably, this snapshot was taken before the COVID-19 pandemic and the financial strains it brought.

Lacking Financial Tools

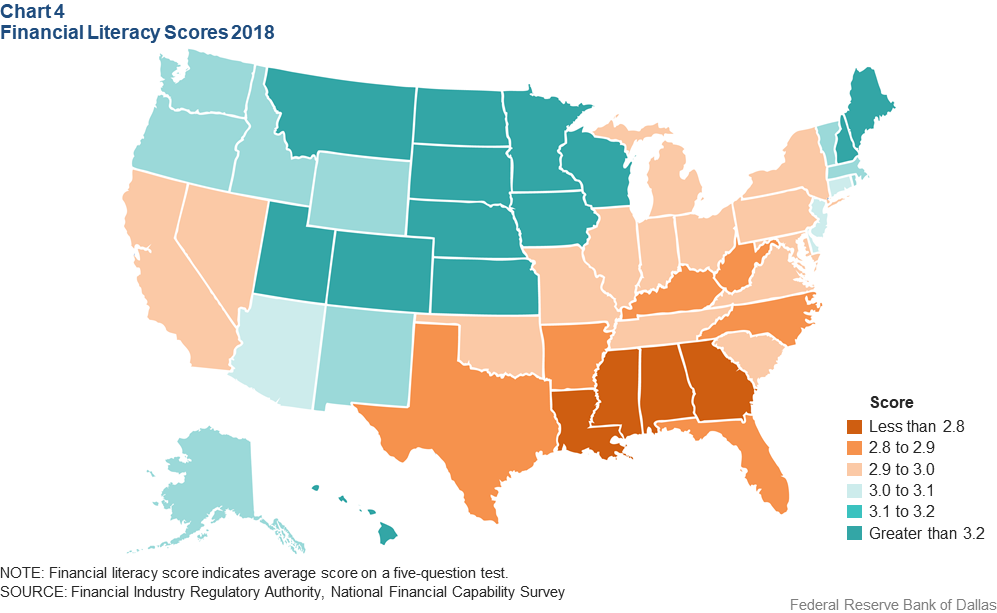

In the five-question quiz portion of the 2018 FINRA study, Texas answered 2.9 questions correctly on average, just below the overall U.S. score of 3.0 questions. Nebraska recorded the highest mean score at 3.4 (Chart 4).[14]

A majority of national and Texas respondents understood interest rates, inflation and mortgages; however, the majority of both groups did not fully understand portfolio diversification and how bond prices respond to changes in interest rates. The result has changed little since 2012.

Texas outperformed the U.S. on understanding that bond prices move in the opposite direction of interest rates—bond prices fall when interest rates rise. Among Texas respondents, 27 percent knew that, compared with 26 percent nationally.

Explaining Poor Ranking

Financial literacy is correlated with a host of socioeconomic and demographic variables, including age, income, education, nativity and race/ethnicity.

Older people generally have more experience and, hence, familiarity with personal finances. The median age in Texas was 34 in 2018, making it the fourth-youngest state. Thus, the state’s relative youth contributes to its relatively low financial literacy score.

Education is another important indicator of how well respondents perform on the quiz questions. Those who have some college education or higher will perform better than those with just a high school diploma or less. Among states, Texas had the highest share of adults ages 25 and older with no high school diploma or equivalent in 2012, at about 17 percent—a figure that was little changed in 2018 and roughly the same as California. It bears noting the low levels of education in Texas overall are predominately due to immigration from low-education countries, such as Mexico. Among U.S.-born Texans, educational attainment gaps vis-a-vis the nation are much smaller.[15]

Race and ethnicity also appear correlated with financial literacy. Blacks and Hispanics score lower than Asians and non-Hispanic whites, perhaps because of lower income and less education on average. Because low-income individuals have fewer resources, the consequences of bad financial decisions tend to be proportionately greater.

Among immigrants, many of them Hispanic, there are also language barriers and cultural differences. Texas has far higher shares of Hispanics and immigrants than the national average. Hispanic residents made up 39 percent of the Texas population in 2018, a share more than twice as large as that for the U.S. (18 percent). Meanwhile, immigrants overall comprised 17.2 percent of the Texas population in 2018, compared with 13.7 percent in the nation.

By comparison, Blacks accounted for 12.1 percent of the Texas population, close to the U.S. figure of 12.7 percent.

The pandemic has brought renewed attention to the need for financial literacy, much as the Great Recession did more than a decade ago. Even in the presence of government assistance, a national study of financial fragility following the onset of COVID-19 in 2020 discovered that feelings of financial insecurity were inversely related to financial literacy.[16]

COVID-19 led to greatest concerns of financial insecurity among respondents under age 60—women more so than men. Blacks’ feelings of fragility exceeded those of Hispanics, both of which exceeded that of non-Hispanic whites. Subsequent pandemic-related economic difficulties tended to prove these anxieties correct, most affecting those who felt insecure, the study noted.

A Lifelong Challenge

Lacking adequate financial literacy creates lifelong challenges to well-being and adds to the growing wealth gap. Those with lower financial literacy have a disadvantage when it comes to accumulating a financial cushion for an emergency or financial planning to build assets in the long run. Missed opportunities for homeownership, financial market investment or retirement savings bear costs for individuals and the communities in which they live.

Those who lack financial literacy are also less likely to understand when to take on debt and when not to, such as borrowing for higher education or to acquire a car.

To promote individual financial success and decrease wealth gaps, financial literacy education has become a priority. Two dozen state legislatures considered bills in 2021 amid the pandemic to bolster financial literacy education, an increase from four states two years prior.[17]

In Texas, the Legislature’s action to increase financial education is part of the broader trend and an acknowledgement that more can be done.

Notes

- “2008 Annual Report to the President,” President’s Advisory Council on Financial Literacy, U.S. Treasury Department, Washington, D.C., p. 4 .

- "Measuring Financial Literacy," by Sandra J. Huston, Journal of Consumer Affairs, vol. 44, no. 2, 2010, pp. 296–316.

- “High School Financial Literacy Mandate Could Boost Texans’ Economic Well-Being,” by Camden Cornwell and Anthony Murphy, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, First Quarter, 2016.

- When evaluating Texas’ overall financial education, The Nation’s Report Card on Financial Literacy gave Texas a “B,” stating that requiring stand-alone personal finance courses could improve its standing.

- Texas Education Code, Title 2, Subtitle F, Chapter 28, Subchapter A (“Essential Knowledge and Skills”), Section 28.0021 (“Personal Financial Literacy”).

- Additional data on financial outcomes by state are available through Propensity Now, a nonprofit seeking economic equity.

- The New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax is a nationally representative anonymous random sample from Equifax credit files. It tracks all consumers with a U.S. credit file residing in the same household from random, anonymous sample of 5 percent of U.S. consumers with a credit file. Equifax data assets are used as a source, but all calculations, findings and assertions are those of the author.

- “An Introduction to the New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel,” by Donghoon Lee and Wilbert van der Klaauw, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 479, 2010.

- “Debt in America: An Interactive Map,” Urban Institute. Data were updated March 31, 2021, from data assembled in December 2020. Accessed Feb. 10, 2022.

- “Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2020,” by Katherine Keisler-Starkey and Lisa N. Bunch, U.S. Census Bureau, September 2021, p. 9.

- “Medicaid Expansion’s Impact in Texas,” The Takeaway: Policy Briefs from the Mosbacher Institute for Trade, Economics and Public Policy, vol. 11, no. 12, 2020.

- “Most Medical Debt Will Be Dropped from Consumers’ Credit Reports,” by Aimee Picchi, CBS News, March 18, 2022. Medical debt is particularly prone to negotiation between providers and patients, which was a factor in the credit bureaus’ decisions.

- The American Community Survey estimates that 20.8 percent of residents under age 65 lack health insurance, .

- As part of the survey, a five-question quiz has been part of the study since 2009. A sixth question was added in 2015 and 2016, asking respondents to estimate the effect of 20 percent compound interest over time. To maintain comparability, this question is not included in summaries of the national test results.

- “Gone to Texas: Immigration and the Transformation of the Texas Economy,” Special Report, by Pia M. Orrenius, Madeline Zavodny and Melissa LoPalo, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2013, p. 5.

- "Financial Fragility During the COVID-19 Pandemic," by Robert L. Clark, Annamaria Lusardi and Olivia S. Mitchell, AEA Papers and Proceedings, vol. 111, May 2021, pp. 292–96.

- “Pandemic Helps Stir Interest in Teaching Financial Literacy,” by Ann Carns, The New York Times, April 2, 2021 (updated Aug. 27, 2021).

About the Authors

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2021/swe2102.