Online retailing, self-employment disrupt inflation

The employment status of increasing numbers of workers has become contingent in recent years—that is, there is greater freelance, or “gig,” employment. This development has coincided over the past two decades with an era of increasing online commerce that provides consumers a wider array of products and services at competitive prices.

Simultaneously, U.S. inflation has become more stable. During the Great Recession, inflation and wages fell by less than what economists expected given relatively high unemployment. They based that belief on conventional Phillips curve models, which suggest that the unemployment rate and inflation move in opposite and proportionate directions.

One reason wage growth has remained unusually subdued could be that the headline unemployment rate has understated the amount of available labor, or labor slack, owing to gig employment.

Unemployment–inflation relationship

Generally, when the unemployment rate is above its “natural rate” (the expected rate as an efficient economy expands), there should be downward pressure on inflation. Furthermore, the speed at which inflation falls depends on the slope of the relationship between unemployment and the change in inflation—a flatter Phillip’s curve implies a slower rate of change.

The experience of the Great Recession and the subsequent recovery taken together suggests that economic slack takes longer to affect inflation (the flatter Phillips curve) and the natural rate of unemployment has fallen.

Transformation of goods, labor markets

These developments have coincided with major transformations in goods and labor markets that may affect aggregate wage and price behavior.

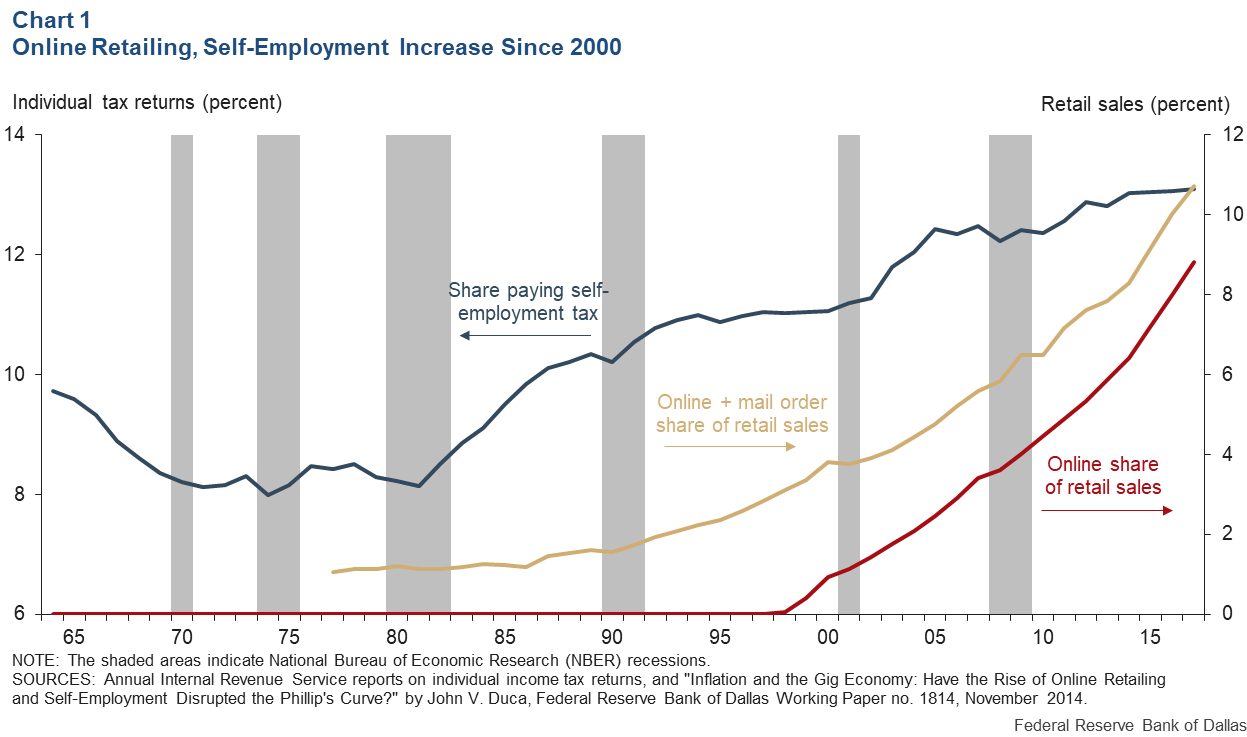

Online shopping as a share of retail sales has dramatically increased (Chart 1). Consumers find lower prices across geographically disparate sources, minimizing local shortages of goods and services and reducing monopoly power.

As a result, when the national economy operates at high levels of capacity, there is less upward pressure on local prices than in the period before the emergence of mega online retailers, such as Amazon. This translates into a flatter Phillips curve.

In labor markets, there has been a rising self- or gig-employment trend, as tracked by the share of households earning enough to pay self-employment tax, as Chart 1 shows. This tax-return-based measure avoids underreporting of gig employment in surveys in which some households report their status as employed even though they’re actually contractors or running a small business.

New technologies that encourage contingent or just-in-time labor (gig employment) lower the bargaining power of workers. This, in turn, lowers the natural rate of unemployment and real equilibrium wages.

Essentially, firms are able to hire contract or self-employed workers, who are not on their payrolls and not counted among the unemployed when not on the job. As a result, the headline measure of unemployment may understate labor slack.

Muted inflation impact

Alone, neither online shopping nor gig employment can account for the recently changed behavior of wage and price inflation.

Though the rise of online shopping can plausibly flatten the slope of the Phillips curve by reducing local bottlenecks and local retailers’ monopoly power, it cannot similarly account for subdued wage growth and changes in labor market practices outside of the retail sector.

While the rise of gig employment helps account for signs of a decline in the natural rate of unemployment and for the subdued recovery of wage growth in recent years, it doesn’t really explain why inflation did not fall more during the Great Recession.

However, modifying Phillips curve models to reflect online shopping and gig employment can help account for a flattening of the Phillips curve and a drop in the natural headline rate of unemployment. Nevertheless, these shopping and employment behavior changes are still new enough that the data are insufficient for full statistical analysis. It will take more observations and analyses to better identify the precise extent of these effects.

Milton Friedman and technology-aided disruption

From a broader perspective, these results are consistent with Milton Friedman’s point that the natural rate of unemployment and its effect on inflation depend on the complete set of microeconomic relationships in goods and labor markets.

The results also are consistent with Friedman’s later observation that the natural rate of unemployment “is not a numerical constant but depends on ‘real’ as opposed to monetary factors—the effectiveness of the labor market, the extent of competition or monopoly, the barriers or encouragements to working in various occupations, and so on.”

The rise of online shopping and gig employment are forms of technology-enabled disruption. They arise from information technologies that improve coordination between buyers and sellers in goods markets and drive the adoption of contingent labor practices.

In this way, they have altered wage and price inflation, making both more stable relative to the past.

About the Author

John V. Duca

Duca is a vice president (part-time) in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas and the Danforth-Lewis Professor of Economics at Oberlin College.

The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.