In uncertain times, Fed sometimes turns to ‘insurance’

In June 2019, a concept appeared in the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) minutes that had not shown up in FOMC minutes for 11 years—the idea of monetary policy “insurance.” The context was St. Louis Fed President James Bullard’s dissent. He argued that a federal funds rate cut could “provide some insurance against unexpected developments that could slow U.S. economic growth.”

A month later, this concept was not just articulated but implemented. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, in the opening statement to his press conference on July 31, said that a just-approved 0.25 percentage-point rate cut “is intended to insure against downside risks from weak global growth and trade policy uncertainty,” among other motivations.

Powell’s statement raises three questions:

- What is insurance, in the context of monetary policy?

- What kind of precedent is there for monetary insurance?

- How has the concept of insurance altered the Fed’s policy process?

A closer look at insurance

In remarks during a March 1996 FOMC meeting, then-Fed Chair Alan Greenspan said “taking out insurance means that we are adjusting policy on the basis of a risk to the forecast that has a low probability of occurring.” In other words, we might expect an insurance cut—or an insurance hike—when the balance of risks shifts, not when there are fundamental changes to economic indicators.

When the Fed sees more downside risks—that is, scenarios that could lead to slower growth, higher unemployment, disinflation or even deflation—it may cut the federal funds rate as a preemptive insurance action. When the Fed sees more upside risks—that is, scenarios that could lead to high inflation, labor market overheating, asset bubbles and other imbalances—it may opt for an insurance rate hike.

Business media have focused on a series of three consecutive rate cuts in 1998 as a prime example of monetary insurance. Yet, it was far from the only time the concept has come up.

When the Fed acted

We examined both the FOMC meeting minutes and the full transcripts in 1994 through 2013 for any mentions of insurance to better understand the recent history of monetary policy motivated by insurance.

After filtering out references to insurance companies, health insurance, crop insurance and other concepts not relevant to our search, we cataloged every mention of insurance that could be reasonably construed to be about either a current monetary policy decision or retrospective mentions of previous insurance-motivated policy actions.

In total, we found nearly 250 such mentions in the transcripts. We also categorized these mentions and used these categories to help identify when there was either broad agreement among FOMC participants that a policy action constituted insurance or competing interpretations (Box 1).

Box 1

FOMC ‘Insurance’ Has Sought to Achieve Policy Objectives

Examples of Federal Open Market Committee participants acknowledging that rate changes constituted insurance to support a particular outcome:

““With inflationary pressures subdued, we have the flexibility to take out some additional insurance against excessive weakness in demand.”

—Philadelphia Fed President Edward C. Boehne, November 1998.

““I see this as a unique opportunity to take out some additional inflation insurance at little or no cost.”

—Atlanta Fed President George C. (Jack) Guynn, August 1999.

“After a series of rate hikes, “today’s move will complete the process of removing the insurance premium that was incorporated into the federal funds rate as an emergency measure.”

—San Francisco Fed President Janet Yellen, November 2004.

Based on this systematic reading of FOMC minutes and transcripts, the past 25 years of Fed monetary insurance comes into focus. In February 1995, the Fed approved an insurance rate hike out of concern that the economy could accelerate too fast, spurring excessive inflation. This insurance was removed swiftly—canceled with rate cuts—within a year.

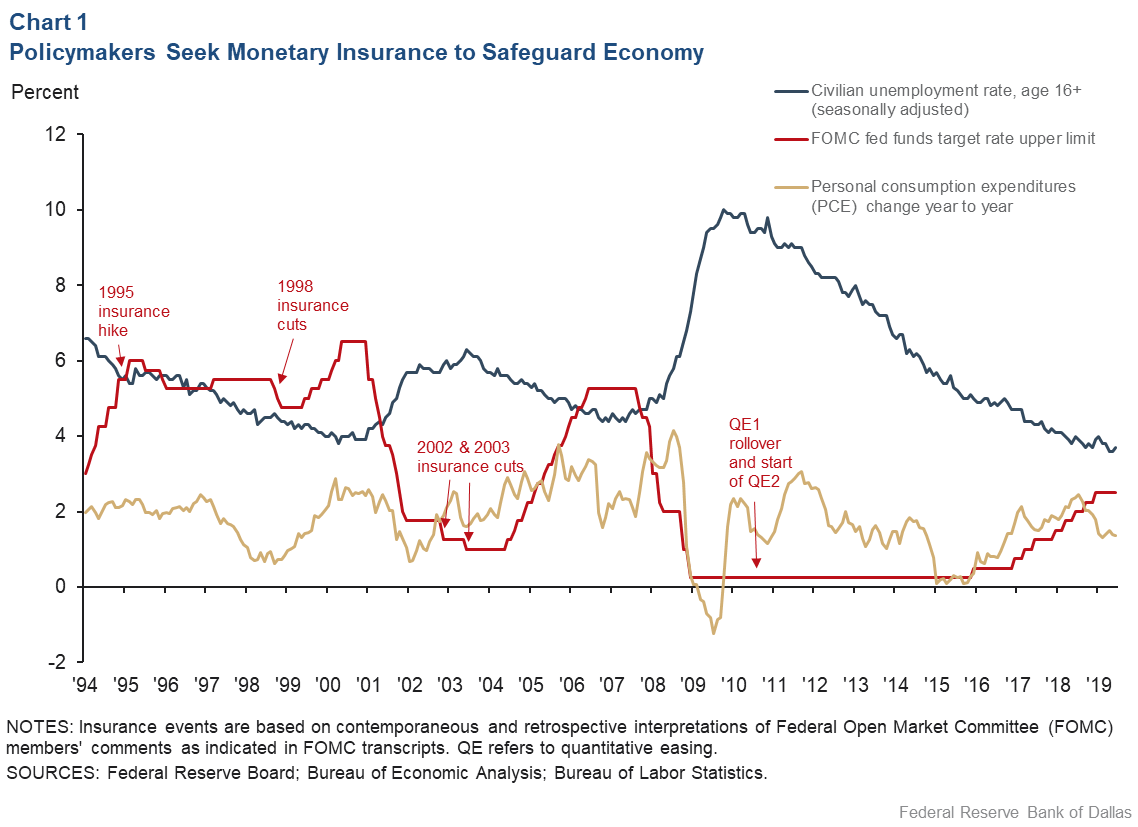

The most-cited and well-known instance of monetary insurance came in fall 1998, when a series of cuts were presented publicly as preemptive risk-management triggered by the failure of the hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) and the Asian economic crisis. The U.S. economy was fundamentally healthy (Chart 1). These cuts were fully offset by November 1999.

The next two unambiguous insurance cuts came in November 2002 and June 2003, spurred by a variety of perceived downside risks ranging from the strictly economic to the geopolitical. Interestingly, many of the rate cuts that directly preceded the Great Recession were framed, at the time, as insurance—until the depths of the recession when, as Cleveland Fed President Sandra Pianalto put it in December 2008, “the insurance metaphor, I think, has been exhausted. We are now more in a situation of treating mass trauma.”

Later, while the federal funds rate stood at the zero lower bound, the transcripts reveal that “insurance” was a key argument made for both maintaining the initial round of quantitative easing (QE1) in August 2010 and the beginning of QE2 in November 2010. In both instances, QE involved the Fed’s purchase of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities to put more cash into the financial system and boost liquidity.

Chart 1, depicting these moves, also shows the performance of the main macroeconomic variables most relevant to the Federal Reserve’s dual mandate of achieving full employment and price stability.

Recent macroeconomic research highlights the importance of acting decisively in the presence of an effective lower bound on nominal interest rates. Some researchers find that the zero lower bound creates an asymmetry—it is easier to tighten policy than to loosen it; it is easier to curb inflation than to raise it.

Compounding these considerations, long-term structural trends suggest that the natural rate of interest—also known as the neutral rate, which is neither accommodative nor stimulative—has fallen gradually over time. This leaves less room for monetary accommodation in general and likely leads to more frequent visits to the zero lower bound.

Unfortunately, lower-bound episodes like 2009–15 require unconventional monetary policy tools of uncertain prowess. A key insight in the academic literature is the greater need for increased risk management at the lower bound. Research also indicates that policy ought to respond rapidly and aggressively to shifts in the balance of risks to ensure against the potential need for unconventional policy tools. In other words, a central bank faced more frequently with the zero lower bound will have to consider preemptive insurance moves more often.

Insurance and the policy process

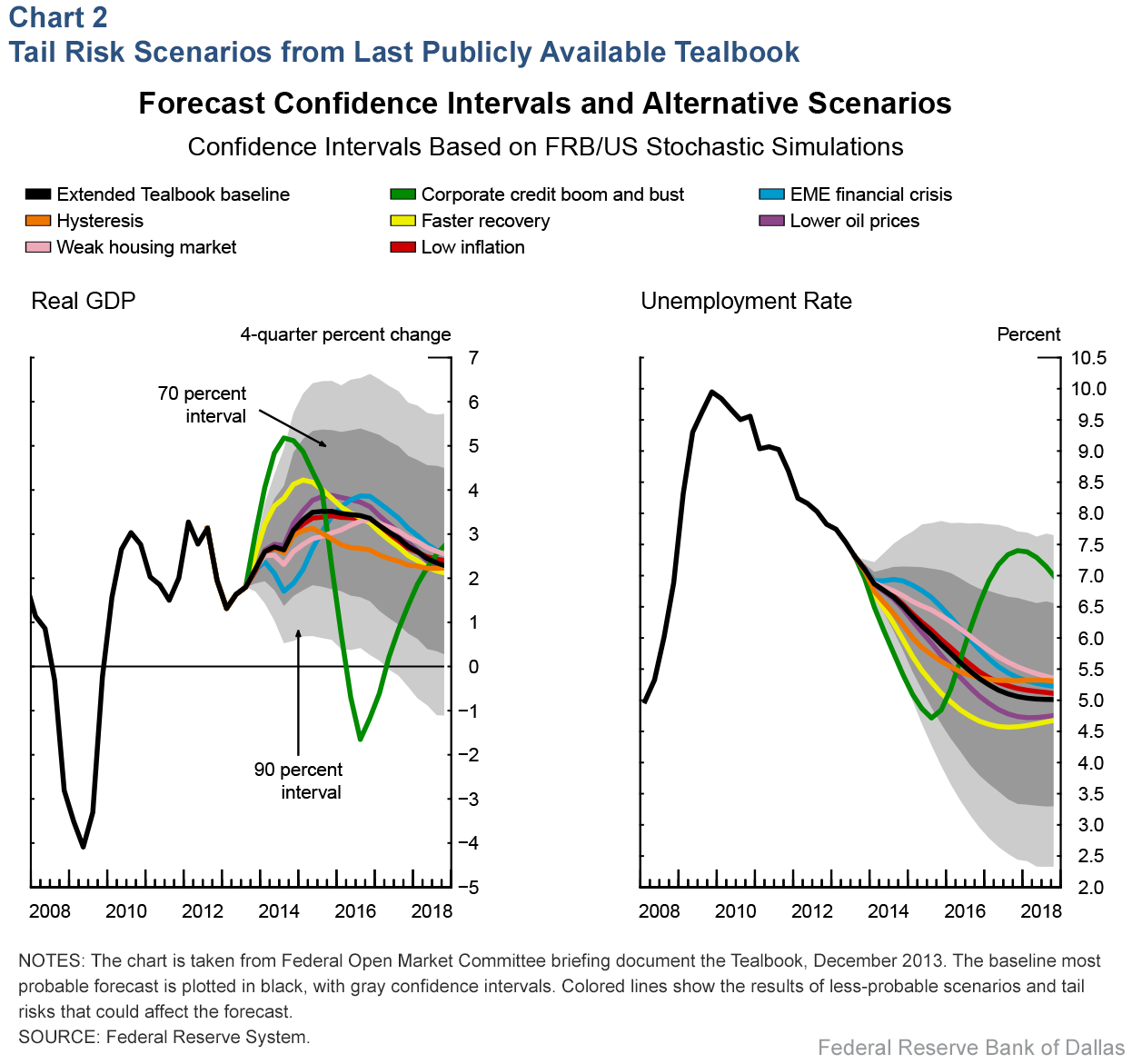

It is unclear whether risk management was always a meaningful part of the Fed’s policymaking process. In the past few decades, publicly available briefing material reveals that the Federal Reserve has increasingly incorporated these uncertainties in its formal briefing process by looking at alternative scenarios—simulations that indicate how various relatively low-probability events could affect the Fed’s baseline forecasts (Chart 2).

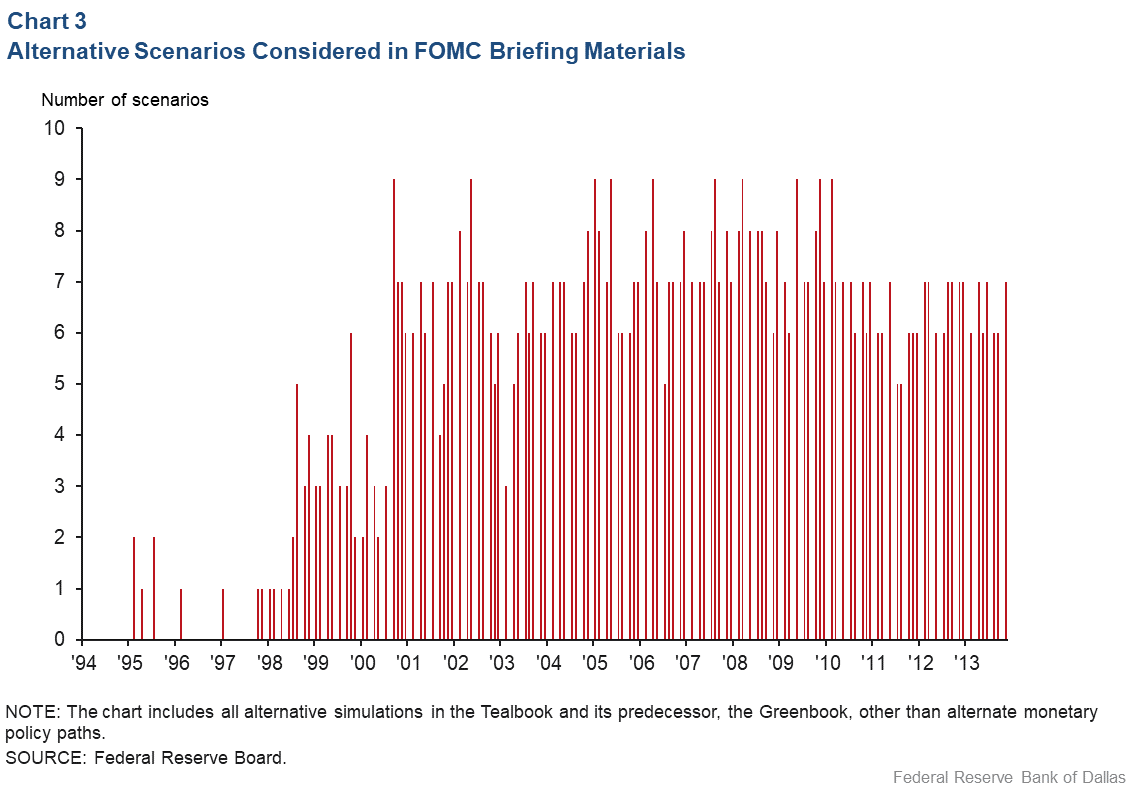

FOMC monetary policy decisions are preceded by a formal briefing process, some of it captured in a briefing document, referred to as the Tealbook, from which Chart 3 is taken. The Tealbook is released to the public five years after the fact. The number of risk scenarios considered changed around 2000 (Chart 3). The first time the Fed incorporated more than a couple alternative simulations into its projections was September 1998. This corresponds exactly to the meeting when the first of the three 1998 insurance cuts was undertaken.

Since then, the Fed has continued to consider a number of alternative simulations, ranging from major stock market booms and busts to potentially contagious slowdowns in major foreign economies. Debate about the zero lower bound erupted in the early 2000s, so it is only natural to think that risk-management concerns became more prevalent in the briefing documents around that time.

The Federal Reserve Board staff’s move to make these scenarios such a prominent and consistent part of the briefing materials reflects a greater emphasis on risk management.

Why does this matter? It means that at every meeting, the Federal Reserve is taking a systematic view of the low-probability events that could shock the economy. It means that even at times when fundamental economic indicators are healthy, the Fed may be spurred to action when it notices a shift in the balance of risks. And it means that the monetary policy practice of taking out insurance is not going away any time soon. It will likely be a focal point of monetary policy debates and decisions for years to come.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.