Global Perspectives: Ruth J. Simmons on trailblazing and education

Ruth J. Simmons, the daughter of a sharecropper, became the first African American woman to lead an Ivy League university, Brown University (2001–12), and before that, Smith College. She is currently the president of Prairie View A&M University, 45 miles northwest of Houston, one of the nation’s historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

A 1973 PhD graduate of Harvard University, Simmons has had a long career in academia. She is a recipient of the President’s Award from the United Negro College Fund, the Fulbright Lifetime Achievement Medal, the Eleanor Roosevelt Val-Kill Medal, the Foreign Policy Association Medal and the Centennial Medal from Harvard University. In 2012, the president of France named her a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor.

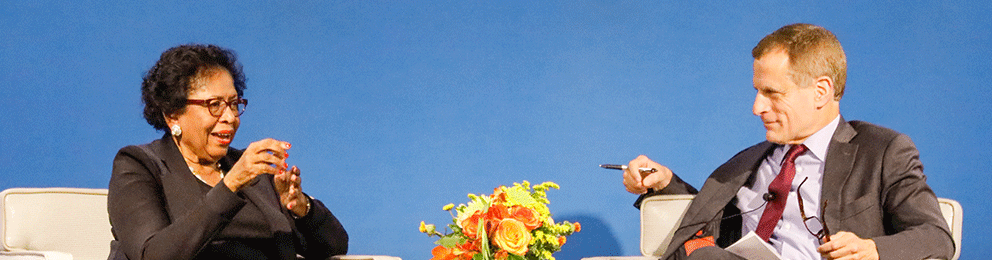

Earlier this month, the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas hosted Simmons as part of the Bank’s Global Perspectives speaker series. This series was launched at the beginning of 2016 with the objective of bringing leaders from the worlds of business, academia and policymaking to the Dallas Fed to share their insights on global, national and regional developments.

Simmons and Dallas Fed President Rob Kaplan discussed her decision to become an educator, her experience in academia and the importance of educational opportunity. The following are excerpts from their conversation, edited for clarity and presented by topic.

On education opening doors:

Simmons: I started my life on a farm in East Texas, in Franklin, a tiny place. The farm that we were on had 100 families on it. I was the youngest of 12 children. I grew up like so many of my students today, in an environment of want. Not having anything, I was enchanted when I went to school. This [was a] place where you didn’t have to go out and work in the fields and you didn’t have to do farm chores; you could actually go to school and learn.

There was a wonderful mediator in the middle of all of this who loved learning. Any time that you did something that was good in terms of learning, you felt that you were at the top of the mountain. That first experience that I had with Ms. Ida May Henderson in Grapeland really started me on that path.

When my family moved to Houston, I had more incredibly inspiring teachers. We came to Houston as, you might imagine, country bumpkins who didn’t fit in. But it was glorious, because as much as we didn’t fit in, and we didn’t have the right clothes and the right hairstyles and all that, as soon as I got to school, I was the star.

And so, [I believed] this whole idea that however people treat you, whatever you possess, your intellect gives you the ability to be on par with anybody. And when I learned that, and the power of learning and the power of knowledge, I just never wanted to leave it.

On the value of candid feedback:

I did my best to try to make a difference every place that I went, to be authentic especially because of all those students who were coming along after me. I was trying to influence the students to understand that they had an opportunity and they should avail themselves of that opportunity, but I never thought I would be able to become a college president.

The most important thing to know is that, when you start on that path to learning, and you work hard at it and you get better at it, there really aren’t any ceilings—unless you impose them on yourself. I was lucky because there were people all around me who insisted that my own thoughts about what I couldn’t do were invalid.

There was a gentleman, Aaron Lemonick, at Princeton [University]. We had very little ostensibly in common. I was obviously reared in the South, African American, Baptist. He was reared in Philadelphia; he was Jewish. He was my supervisor, and he absolutely pushed me to do more than I thought I could. More importantly, he also criticized me.

A lot of what happens to women and minorities in the workplace is that people kind of tiptoe around us and won’t tell us the truth. So, when we’re performing poorly, they don’t tell us. But others, they go and say, “Look, you need to do this, and you’ll improve if you do that.” We don’t get that because there is a kind of barrier that says, “No, you better not say that.”

Well, he broke all those barriers. I remember one day I worked up a spreadsheet on salaries. I did the faculty salaries at Princeton, and I gave it to him [Lemonick]. He said it was the worst thing he had ever seen in all of his career. He said to me it was awful, and to punctuate that, he kicked the furniture. I was there with him alone. I was terrified.

And so, I did what any respectable person would do. I went back to my office and put my head on my desk and cried, and I cried and cried and cried. But then I got up and redid it. [It was] because he would tell me what I needed to improve. Oh, my goodness, what a blessing that was.

On creating equality of opportunity and dealing with the past:

When it comes to children, I don’t believe that anyone needs to be privileged. I think, a child is a child, is a child. What I would want to see is for every single child, sitting in every seat, to have the advantage of a good start in life, regardless of what has happened before. We are prisoners of our history, all of us. Whatever has happened before, we need to adjudicate that. But a child is a child, is a child, and I would like to see us uniformly agree that every child deserves that good start in life.

When it comes to college education, you’re probably aware of what some universities have done recently in regard to their own past with slavery. They are coming out with different outcomes depending on the university, and my guess is we’ll never really have a uniform outcome. There might be some university that is inclined to say that African Americans should not pay tuition because of particular things that happened to them during the period of slavery; but not all will. So, I don’t think that’s a solution.

I’m more concerned about a uniform solution for our children. What can we do that will have the most impact? First is the fact that we live in a community. I depend on you and you depend on me. Now, that very fact means that there are some things that we have to negotiate. We have to agree on how we’re going to operate together. The best way to do that is for everybody to really be completely open to the idea that conversations need to take place. And when those conversations take place, we don’t bring anger, we don’t bring recrimination, we don’t bring all of that baggage to it because that stops the conversation dead cold.

This country is not yet engaged in that. We are lumbering along to that point, and we may get there eventually. Right now, we are in dire need of it because what we’re doing is exercising our opinions with violence, with unhealthy behavior.

Education can help if we get every child a fair start, and we educate them appropriately. That’s a really good way to begin that healing process in this country where everybody has a fair chance and a good start.

On the importance of academics:

A university is, first and foremost, an academic institution, and guess what has to come first in a university? Academics. You can talk about the climbing walls, you can talk about the landscaping, you can talk about everything else you want to talk about, but if it’s rotten at the core in terms of the curriculum, in terms of the faculty’s ability, in terms of what you’re demanding of your students, it’s no good.

My passion is to make sure that we stay focused on the important things and that is offering the best education we can to our students. I don’t want to hear anybody tell me that we ought to be doing something different from that because the students are needy, because the students need time to catch up.

About the Author

Mark A. Wynne

Wynne is vice president and associate director of research in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.