The long road to housing finance reform: 'Are we there yet?'

The Trump administration has released a plan proposing administrative and legislative changes that would return mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to the private sector after more than a decade under federal control.

In the absence of legislation, administrative changes include recapitalizing the two institutions at levels that their federal regulator will establish and extending the emergency federal backstop for their operations in perpetuity.

The measures follow steps the federal government took in 2008 to rescue Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—collectively known as government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs)—after the housing collapse that contributed to the 2008–09 U.S. financial crisis. As part of the planned recapitalization, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will emerge from federal conservatorship.Over the past decade, legislative reforms for housing finance have proven elusive. However, reflecting lessons from the financial crisis, a political consensus has emerged that reformed GSEs (or other federal mortgage guarantors) should operate with:

- More capital.

- Access to an explicit and priced “full faith and credit” federal guarantee for mortgage-backed securities.

- Stringent investment limitations.

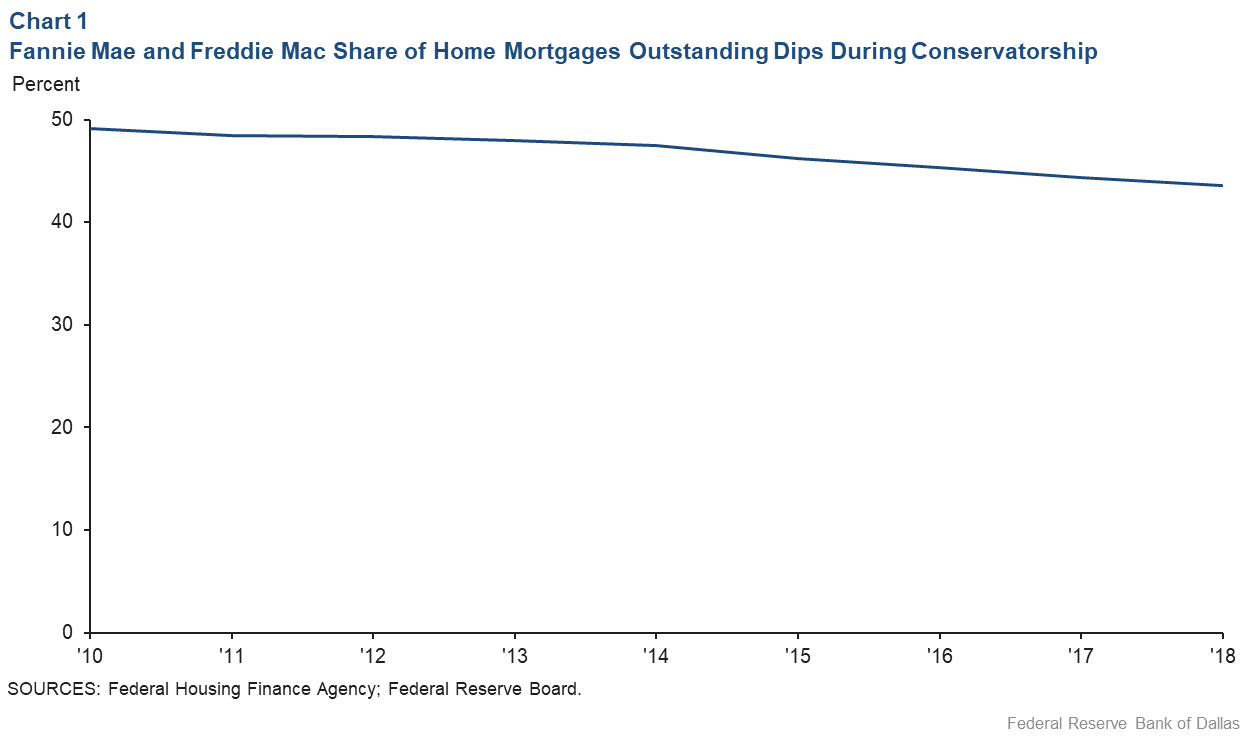

Any plan to recapitalize and release Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac requires striking a balance between making the GSEs an attractive investment opportunity and protecting taxpayer interests. It also requires sensitivity to the fact that they collectively hold or guarantee almost one-half of all outstanding home mortgage debt (Chart 1).

Initial steps of recapitalization

The GSEs’ federal regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), has taken initial steps toward the recapitalization. The first is establishing new minimum capital requirements for the GSEs. This will provide their management a target for earnings retention and guide any subsequent efforts to raise outside capital. It will also aid investor valuation of the GSEs post-conservatorship.

Before the federal takeover, the GSEs were subject to a statutory minimum capital requirement equal to the sum of 2.5 percent of their on-balance-sheet assets, plus 0.45 percent of the credit guarantees underpinning their mortgage-backed securities held by outside investors.

The financial crisis demonstrated that these capital requirements were insufficient to prevent the GSEs from becoming severely distressed. The FHFA proposed new capital standards in June 2018 using authority granted by the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008. The regulator has said it intends to submit a slightly modified rules package sometime this year.

Other recapitalization steps will likely include Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac providing to the FHFA satisfactory capital restoration plans and the regulator clearly defining its role during the GSEs’ transition back to private control. Additionally, the Treasury must agree to an amendment to the preferred stock purchase agreements that mandated a “sweep” of all GSE profits to the federal government.

These steps will allow the two GSEs to retain earnings and begin the process of rebuilding their capital toward meeting the newly established minimum requirements. A 2019 modification to the Treasury’s support agreements provides for some earnings retention by Fannie Mae ($25 billion) and Freddie Mac ($20 billion)—amounts roughly equal to the GSEs’ earnings in 2017 and in 2018.

Follow-on steps for recapitalization

Building the required amount of capital exclusively through retained earnings would take many years. For example, a minimum capital requirement of 3 percent on the $5.5 trillion in combined total assets as of year-end 2018 would imply $165 billion in capital—and this does not account for any additional amounts that would be required under a risk-based standard. Regulated financial intermediaries often must maintain such an added buffer when they assume what is perceived as greater-than-usual risk.

To rebuild their capital more quickly, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac could raise equity in capital markets. While neither the Trump administration nor the GSEs has opined on the mechanics of a public capital offering, a prominent proposal compiled by advisers to a shareholder group outlines one way that it could be done. The advisers envision Treasury selling Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac shares in a manner similar to share transactions involving two other rescued firms—insurer AIG in 2012 and Ally Financial Inc. (formerly a part of General Motors Corp.’s credit unit, GMAC) in 2014.

In the proposal’s hypothetical example, the Treasury transaction would have three parts. First, senior preferred shares issued in return for $190 billion in Treasury funds used to stabilize the GSEs would be extinguished, with taxpayers’ investment deemed to have been repaid through the preferred shares’ 10 percent dividend. Second, the federal government would exercise warrants for up to 79.9 percent of the GSEs’ common equity. Finally, the common stock received via the warrants would be sold to the public.

The Treasury plan states that, absent comprehensive legislation, there should be a post-conservatorship preferred stock purchase agreement that defines the Treasury’s ongoing support for the two institutions, including commitment amounts and associated fees.

A critical legal issue is whether the Treasury’s temporary emergency investment authority granted during the financial crisis can be extended indefinitely without congressional authorization. To limit risk and refocus the GSEs’ mission, the Treasury also indicates that the post-conservatorship agreements should continue to limit the GSEs’ retained investment portfolios and restrict the acceptable types of mortgages that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac could purchase or guarantee, such as cash-out refinances and investor loans. Such restrictions would reduce taxpayer risk exposure but could also temper investor enthusiasm.

Unfinished post-housing-crisis business

The conservatorship of the GSEs is a significant piece of unfinished business from the financial crisis. The Trump administration has proposed administrative changes aimed at finally ending the conservatorship and returning Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to the private sector. The goal is to reduce taxpayer exposure to the GSEs by requiring more capital and limiting the firms’ scope, although the crisis-era Treasury backstop would remain in place and be paid for through a fee.

The $100 billion question is whether there will be sufficient depth of investor interest in the shares of the reformed institutions.About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.