Falling rates no assurance of homeowner refinancing binge

When the Fed lowers its benchmark policy rate, the reduction is usually reflected in a variety of interest rates. Home mortgage rates often follow suit, though they reflect a range of economic factors and inputs such as the yield on 10-year Treasuries.

The average interest rate on a new 30-year mortgage stood at 6.8 percent in July 2025, according to Freddie Mac (the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corp.). By comparison, the rate was just 2.7 percent in January 2021, the lowest since 1971.

With many homeowners holding mortgages around the low, would a softening interest-rate environment leading to a reduction of the 30-year rate by 1 or 2 percentage points dramatically change the economic burden of current homeowners?

There are reasons to believe that such a reduction might not prompt an increase in the volume of mortgage refinances and prepayment activity as has historically occurred. The savings from mortgage prepayment would likely be smaller in the aggregate because most homeowners locked in relatively low rates before the Fed’s most recent tightening cycle began in March 2022. Additionally, many borrowers do not prepay even when doing so would be beneficial.

To further explore this, we leverage the ICE, McDash dataset. It consists of the portfolios of the largest U.S. mortgage servicers, covering two-thirds of loans in the residential servicing market (approximately 34 million loan-level records per month). We then combine ICE, McDash with Home Mortgage Disclosure Act public data for our analysis.

Refinancing often profitable when rates decline

Interest rates generally decline as monetary policy eases—part of a sometimes complex rate-setting mechanism. The drop creates new financing options for mortgage borrowers. Homeowners who refinance obtain new loans at a lower market rate. Others might consider cash-out refinancing, taking out new, larger loans (often reflecting property value appreciation) at lower rates. Borrowers “cash out” the difference between their old and new loans, pocketing that money for other uses.

Home equity lines of credit offer access to revolving credit limited to the amount by which a home’s current market value exceeds the remaining mortgage balance. These instruments can become more attractive as interest rates decline.

In short, lower interest rates can increase the amount of money homeowners have available for consumption and savings. The impact of rate declines on prepayment and interest savings is highly related to rate gaps, the difference between the rate paid on an existing mortgage and the current market rate.

Prepayment savings likely lower when monetary policy next eases

During the last easing cycle, in 2020, refinancing saved borrowers an estimated $24 billion annually. In a potential future easing period, the anticipated rate of savings would likely be significantly smaller. Many homeowners would choose not to refinance because they locked in lower rates before the federal funds rate headed higher in 2022.

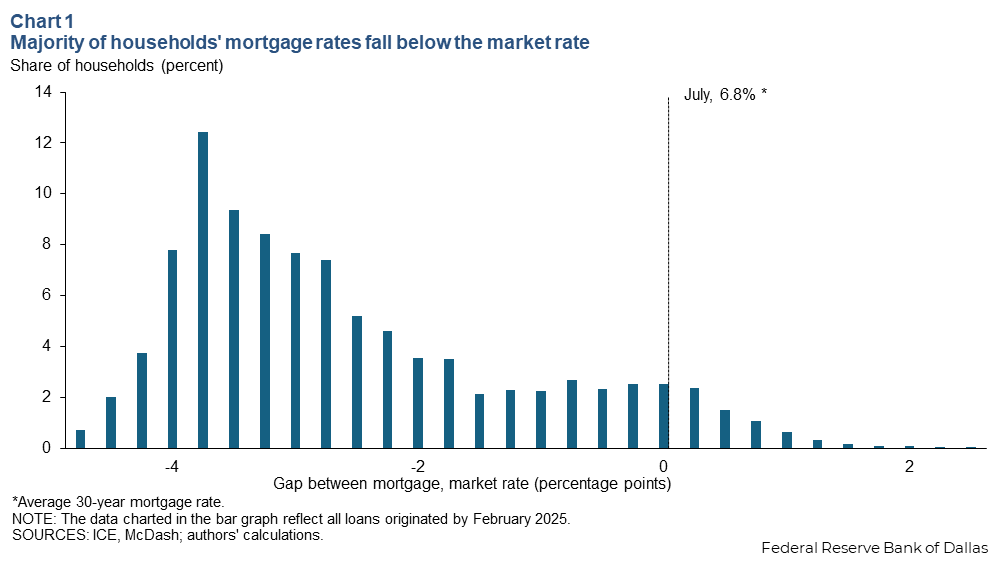

As of July 2025, the average interest rate for a 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage was 6.8 percent, with only 9 percent of mortgages exceeding that rate (Chart 1). If the market rate declined to 5.8 percent, 19 percent would exceed it; at 3.8 percent, 41 percent would exceed it. Overall, as the pool of outstanding mortgages becomes more seasoned, the proportion of borrowers who could save through refinancing changes.

Low-income borrowers less likely to prepay

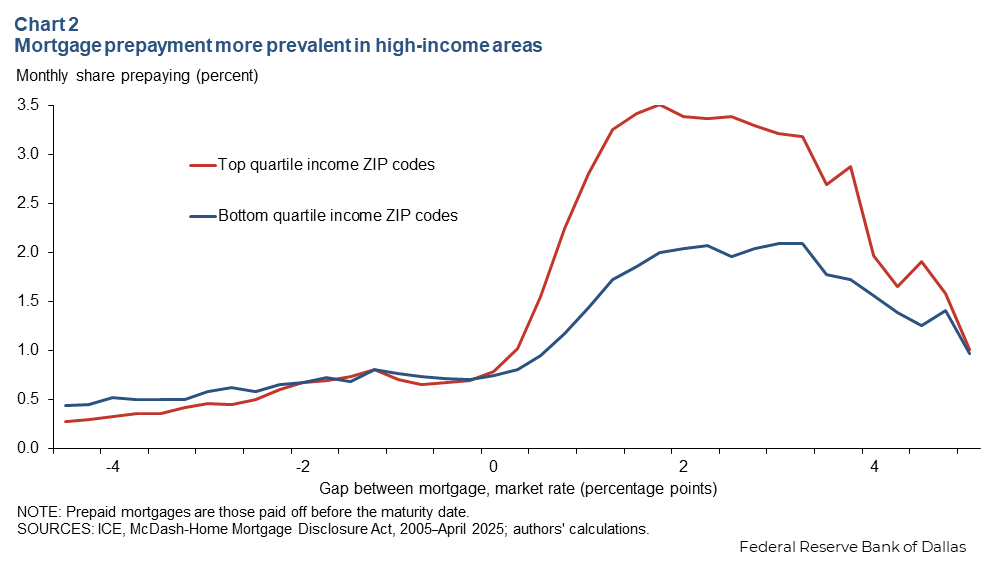

Even in the presence of a positive rate gap, borrower decisions appear to vary based on whether homes are in low- or high-income neighborhoods. Under identical rate gaps, borrowers from high-income neighborhoods prepay with greater frequency than their counterparts in low-income neighborhoods (Chart 2).

When homeowners could benefit from taking action, at least one in five fails to do so. Literature suggests that inattention to potential gains and failure to take timely action are most commonly to blame.

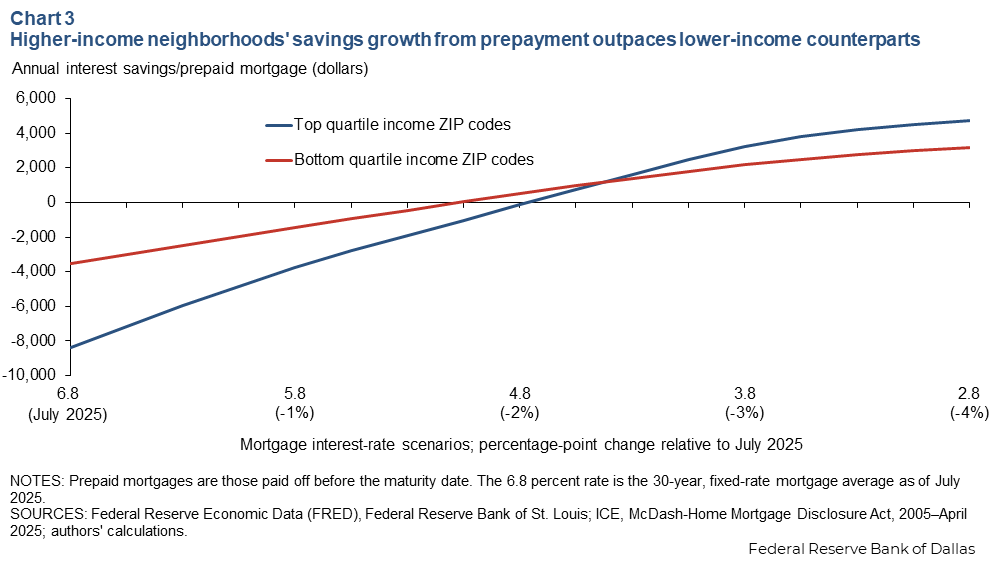

Because borrowers from low-income neighborhoods refinance less frequently, they tend to pay relatively higher mortgage rates. Mortgage interest savings from refinancing also differ by neighborhood. The gap can be wide and meaningful when the interest rate decline is pronounced (Chart 3).

When interest rates drop to a point where both low- and high-income neighborhoods can experience potential positive savings from refinancing, aggregate savings grow faster in higher-income neighborhoods than in lower-income neighborhoods. This reflects larger loan sizes and greater refinancing frequency among higher-income borrowers.

If the 30-year mortgage rate returns to prepandemic levels of 3.45 percent, the gap in annual savings between low-income and high-income neighborhoods could be as high as $1,000 per household. Building awareness about refinancing opportunities could help create economic gains for borrowers across all income levels.

About the authors