Ability to repay a mortgage: Assessing the relationship between default, debt-to-income

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), created in the aftermath of the 2007–08 financial crisis to represent consumer interests in regulatory matters involving financial institutions, has announced that it intends to change the definition of a “qualified mortgage.”

Specifically, the CFPB proposes to reconsider the use of a borrower's debt-to-income ratio as a measure of the ability to repay a loan.

Dissonance between policy, goals

Provisions of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, enacted after the financial crisis, require mortgage originators to make a reasonable and good-faith determination—based on verified and documented information—that a consumer has the ability to repay a loan at the time it is consummated. (The notion that lenders should verify borrower financial information and not originate unaffordable mortgages would strike many as sensible policy following the housing crisis.)

The statute also articulates a presumption of compliance for “qualified mortgages,” or QMs, which the CFPB was to specifically define. Associated regulations were finalized in 2014.

The CFPB’s 2014 rule laid out minimum requirements that lenders apply when making ability-to-repay determinations. It also said that borrowers of qualified mortgages could not have a debt-to-income (DTI) ratio—total borrower monthly debt service obligations as a share of monthly gross income—above 43 percent.

Borrowers with DTIs exceeding 43 percent have little leeway when trying to make their mortgage payments if their income declines. However, the CFPB waived this DTI limit for loans held or guaranteed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) that collectively hold or guarantee almost one-half of all outstanding home mortgage debt.

The waiver involving Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which were placed in federal conservatorship in 2008, is scheduled to last as long as they remain in conservatorship or until January 2021. It is also notable that mortgages guaranteed by the Federal Housing Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs and the Rural Housing Service are subject to their own program-determined rules that do not include the 43 percent debt-to-income limit.

Taken together, this means that the 43 percent DTI rule did not apply to the vast majority of mortgages originated over the past six years—an example of policy dissonance between policy goals, implementation and outcomes.

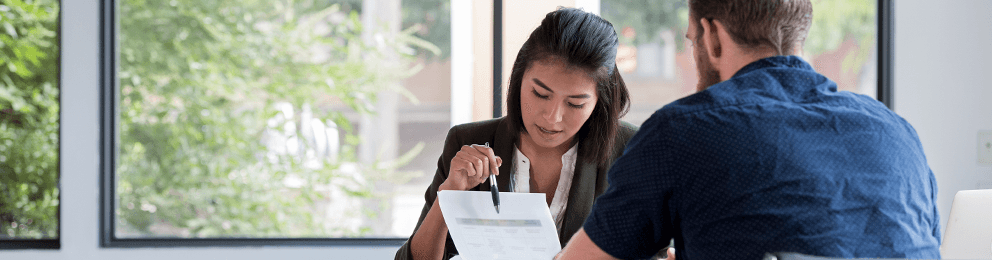

The waiver for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—commonly referred to as the “QM patch”—tilts the regulatory playing field in favor of the two GSEs. This has become increasingly important as the share of their business exceeding the DTI threshold has grown since 2010 (Chart 1). In 2017, nearly one-fourth of all mortgages acquired by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had a DTI ratio exceeding the 43 percent threshold.

DTI ratio, mortgage default relationship

The CFPB has indicated that it may eliminate the 43 percent DTI threshold in its qualified mortgage rule. The Urban Institute, a social policy think tank, and the Mortgage Bankers Association have expressed support for removing the threshold, while other interest groups representing consumers and lenders have advocated for keeping the restriction, but perhaps modifying it to include compensating factors such as higher down payments.

It’s important to look more closely at the relationship between DTI ratios and mortgage default rates to see if higher ratios—especially those exceeding the 43 percent threshold—pose a greater default risk.

To do this, we use large mortgage databases that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac make publicly available in support of their credit risk transfer programs. We specifically examine fully documented 30-year, fixed-rate mortgages originated between 2000 and 2015 (approximately 30 million loans). We focus on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac loans because they are currently exempt from the 43 percent DTI threshold and, unilke other sources, these data include complete and consistent DTI information over time.

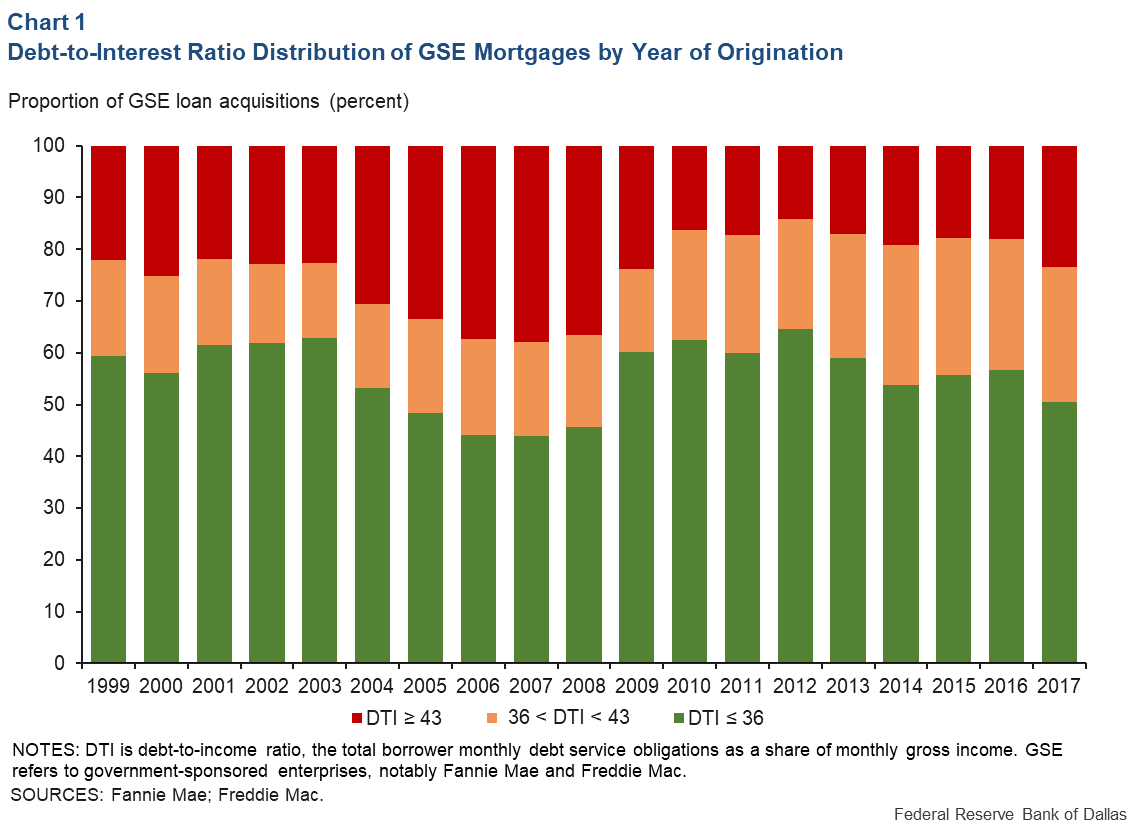

Chart 2 shows the unconditional relationship between DTI ratios and default rates in the data. We focus on three-year default rates because default early in the life of a mortgage is indicative of potential problems with the borrower’s ability to repay. Default is defined as occuring when a borrower is at least 90 days past due on mortgage payments, within three years of the origination date.

For simplicity and ease of interpretation, we split the distribution of DTI ratios into three bins: DTIs less than or equal to 36, DTIs between 36 and 43, and DTIs greater than or equal to 43. We also consider four mutually exclusive loan vintages: 2000–03 loan originations, which correspond to the pre-boom period; 2004–07 originations, which include the boom period; 2008–11 originations, which include the financial crisis period; and 2012–15 originations, which correspond to the recovery period.

There is a clear, positive relationship between the DTI bins and three-year default rates. The relationship is much more pronounced for the boom and crisis periods, which were characterized by significantly higher defaults compared with the pre-boom and recovery periods. The relationship is starkest for 2008–11 vintages; default rates for DTI ratios above the 43 percent threshold are more than four times higher than those associated with DTI ratios below 36 percent.

Predictor may encompass several factors

While the evidence in Chart 2 suggests that DTI ratios may be an important predictor of mortgage credit risk, these are unconditional correlations. In other words, they do not account for the possibility that mortgages with high DTIs may have other risky characteristics, such as low credit scores or high loan-to-value ratios. These characteristics may be even more important predictors of higher default rates—that is, high DTIs may be guilty by association with other risk factors.

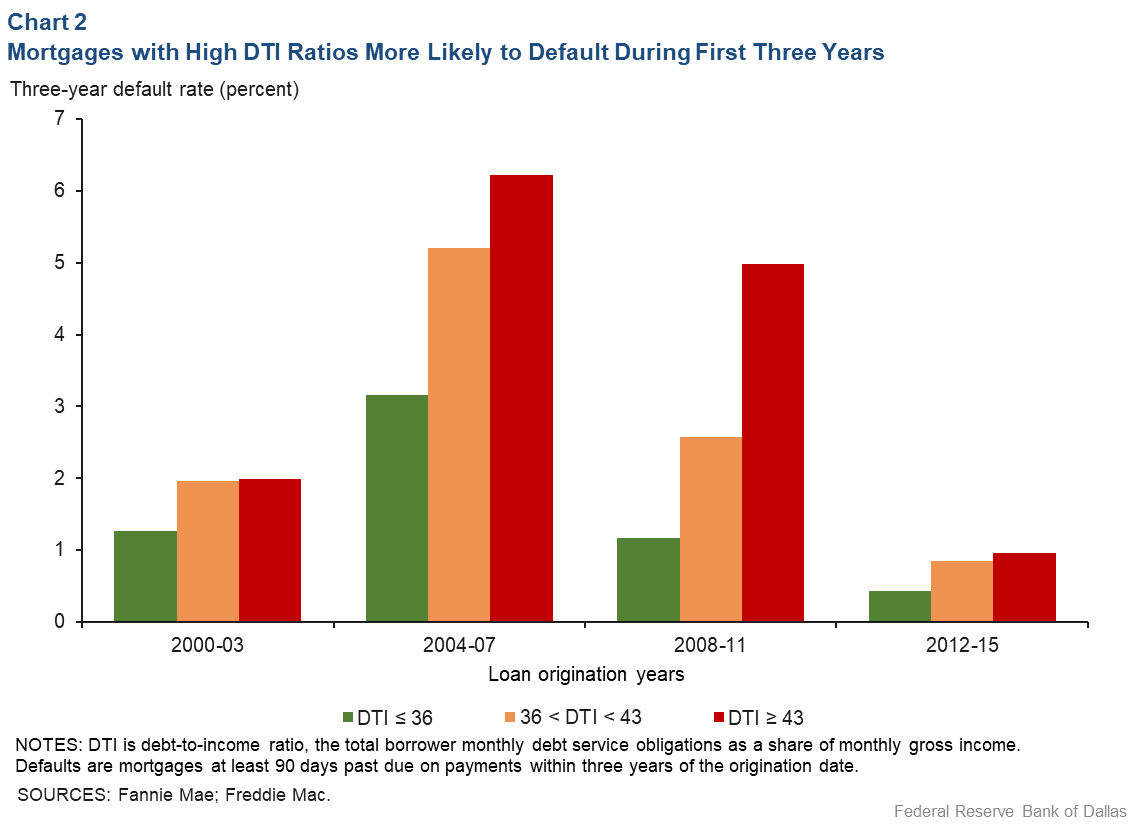

Chart 3 depicts default rates on mortgages that are conditional on some basic underwriting characteristics at origination. Instead of actual default rates, the vertical axis displays predicted three-year default probabilities based on simple regressions that control for loan-to-value ratio, credit score and loan purpose (purchase versus refinance). Probabilities are calculated for a hypothetical home-purchase mortgage that has a FICO credit score of 700 and a loan-to-value ratio of 80 percent.

While there are some subtle differences between Charts 2 and 3, the basic patterns are the same. There is a positive relationship between DTI ratios and default risk—even after controlling for loan purpose, credit score and loan-to-value ratio. For mortgages originated in 2000–03 and 2012–15 that were not exposed to the financial crisis in their first three years, the default rates were 31 percent to 58 percent higher for those with high DTIs (greater than or equal to 43) compared with low DTIs (less than or equal to 36).

Among mortgages originated in the eight years from 2004 to 2011—the period covering the housing collapse and financial crisis—the default rates were 77 percent to 99 percent higher for high DTIs than for low DTIs.

The effect of DTI on mortgage default is clearly magnified during periods of economic stress, the charts show. Loans originated between 2004 and 2011 had significant exposure to the housing bust and recession—featuring severe house price declines and high unemployment rates.

DTI isn’t strongly related to default for mortgages originated between 2012 and 2015, but that does not mean high DTI mortgages are no longer risky. Rather, the economic recovery suppressed their higher risk, which would likely reemerge if the economy were to go into recession.

Lingering issues with high debt-to-income

Our analysis suggests that high DTI ratios are associated with a greater incidence of mortgage default, even after controlling for other borrower and loan characteristics. This relationship appears muted during strong housing markets but much more pronounced during periods of market stress.

We intend to conduct more in-depth analysis to ensure that the positive relationship between DTI ratios and default is robust. Nonetheless, we think this analysis will be helpful in policy deliberations about the ability-to-repay rule.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta or the Federal Reserve System.