Working from home during a pandemic: It’s not for everyone

As the coronavirus (COVID-19) continues spreading in communities across the country, shelter-in-place mandates have sent nonessential workers home. For many, this requires that they work remotely and conduct business using electronic means of communication. Remote workers can remain productive and earn an income while partially shielded from the negative shock of workplace shutdowns.

However, for a large segment of the workforce, remote work is not an option. Restaurant wait staff can only provide their services to diners in restaurants. Dentists deliver their services at clinics. Retail salespeople interact with customers in stores. For those workers, the closure of their businesses due to COVID-19 means they could be sidelined and without income.

Because working remotely can offset the negative effects of shelter-in-place and social distancing policies on employment and earnings, knowing how many workers can do so is crucial to understanding the impact of such measures on our workforce.

Measuring remote compatibility

Since the COVID-19 outbreak is unprecedented, historical data relating to remote work likely provide a misleading assessment of the types of jobs that are remote-compatible. Most of the occupations that can be performed at home during a pandemic would be done in the workplace during normal times because face-to-face interaction, though temporarily nonessential for some jobs, is productive in the long term.

Thus, a simple calculation of the fraction of occupations that could be performed remotely during normal times provides an inaccurate assessment of any single occupation’s potential for short-term remote-compatibility during a pandemic.

To provide a better gauge, a novel method is used to examine the compatibility of remote work from home for each occupation using data on occupational characteristics provided by a U.S. Department of Labor database called O*NET (Occupational Information Network).

O*NET data provide a detailed assessment of the ability and skill required, as well as the physical, social and organization factors involved in each occupation, based on large-scale national surveys. Drawing on occupational compatibility with remote working revealed in the data, it is possible to better understand which workforce segments have a remote work option.

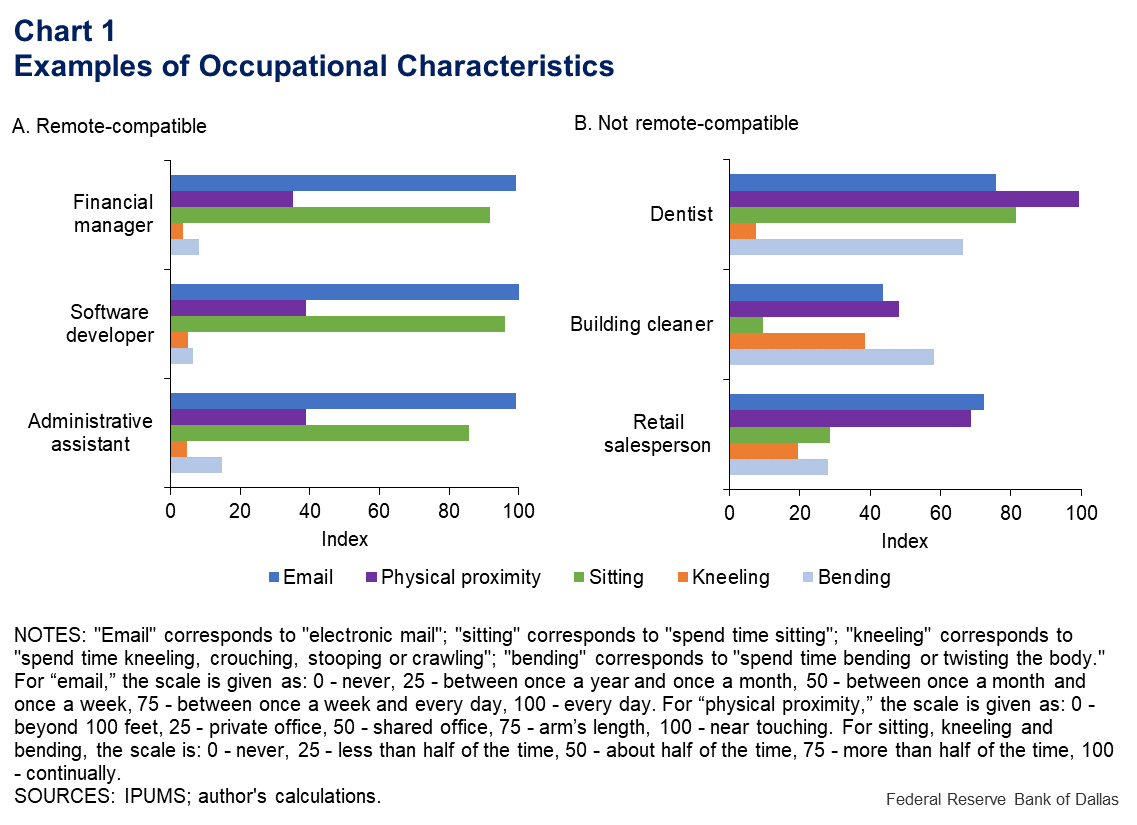

The method presented here categorizes each occupation into either remote-compatible or remote-incompatible, based on five work context indexes provided by O*NET. An occupation is remote-compatible if five criteria are all met:

- Work involves frequent use of email.

- Work does not require physical proximity with other people closer than arm’s length.

- Work involves sitting at least half of the time.

- Work does not involve significant kneeling, crouching, stooping or crawling.

- Work does not involve significant bending, or twisting of the body.

Each criterion speaks to an aspect of remote work. For example, the frequency of using email is a good proxy for how much of a job’s tasks can be conducted through electronic means of communication. Jobs in which electronic communication is already an essential part of the job can likely adapt to remote working easily.

Occupations requiring physical contact with colleagues or customers, such as dentist, clearly are incompatible with working remotely. Jobs for which a lot of standing or physical movement is required—such as flight attendant or retail salesperson—are unlikely to be adaptable to working from home. Similarly, jobs requiring strenuous body motions—such as cleaner and plumber—probably aren’t candidates to be performed from home.

This method of assessing remote-compatibility is clearly imperfect. Some jobs may not be remote-compatible given their usual job routines but may become remote-compatible under extraordinary circumstances. For example, working remotely is typically not an option for K-12 teachers. However, in many school districts, teachers have continued to teach their students remotely.

Moreover, other factors that can’t be fully taken into account could affect the feasibility of working at home. During the coronavirus emergency, for example, children who are home because of shuttered schools may interfere with remote work.

Applying the five criteria, 132 out of 400 occupations were identified as remote-work compatible. A list of occupations that are compatible and incompatible with remote work and their associated occupational indexes is available here.

For perspective, Chart 1 shows three common occupations each from the remote-compatible category and from the not-remote-compatible category, and their work context characteristics.

Who can work remotely?

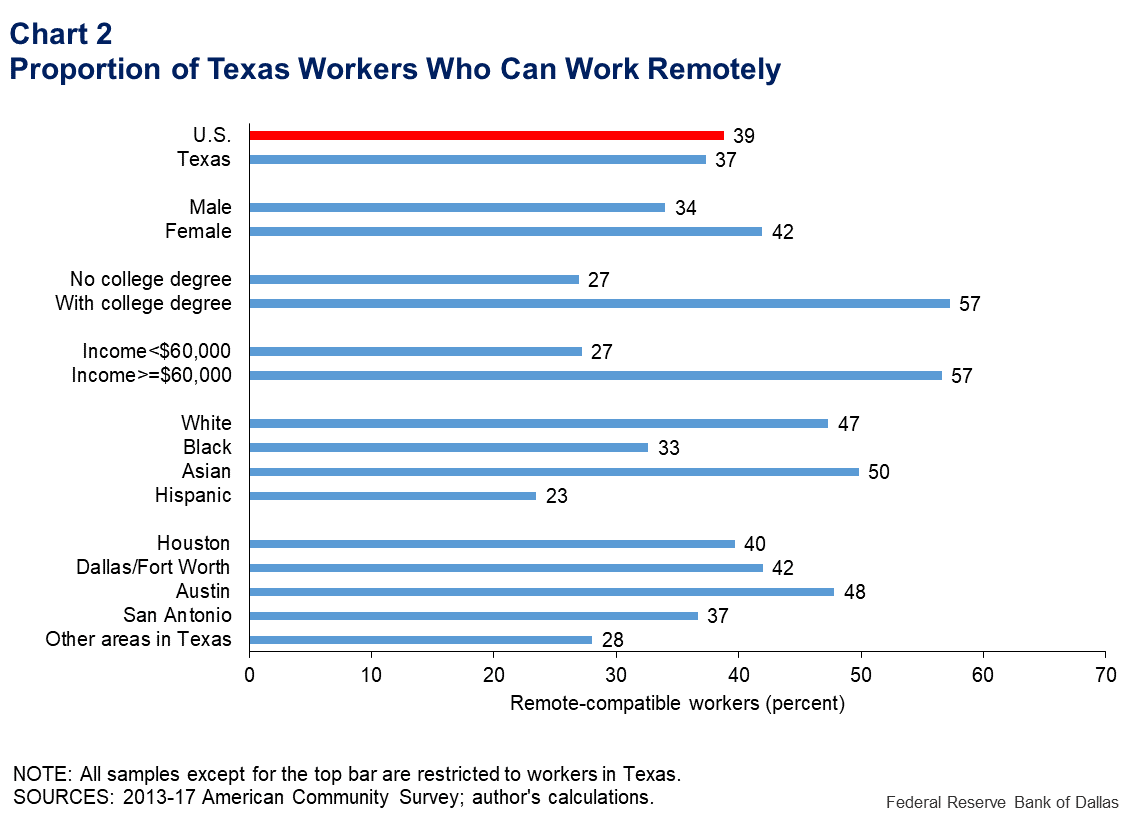

Chart 2 shows the proportion of employed Texas workers holding remote-compatible jobs. People in occupations compatible with operating remotely from home constitute about 38.8 percent of full-time workers in the U.S. and 37.3 percent of full-time workers in Texas.

Female workers are more likely to have jobs for which the remote working option is available.

Workers with college degrees and those earning $60,000 or more are far more likely to be in jobs for which remote working is an option than those without a degree or earning less than $60,000.

Asian workers are the most likely to hold remote-compatible jobs, with white workers right behind. Black and Hispanic workers are significantly less likely to work in remote-compatible jobs.

Within Texas, workers in the four largest metropolitan areas are more likely to have remote arrangements available than their counterparts elsewhere in the state. Austin has the highest percentage of workers with a remote working option; Dallas and Houston are just behind. San Antonio has the smallest proportion of remote-compatible workers.

These findings show that more than half of jobs in Texas and in the nation are incompatible with working remotely. Low-income workers and minorities, in particular, are much less likely to have the option to work remotely. Thus, worksite shutdowns would likely affect more than half of the workforce, particularly the segments that are already comparatively vulnerable. This division is likely to more fully emerge as a concern as the crisis continues unfolding.

About the Author

Yichen Su

Su is a research economist in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.