Emerging-market eeconomies face COVID-19 and a 'sudden stop' in capital flows

Emerging-market capital inflows dramatically declined in response to the rapid spread of the coronavirus (COVID-19). A rise in global risk at a time of investor risk aversion led to a rapid flight from emerging-market assets.

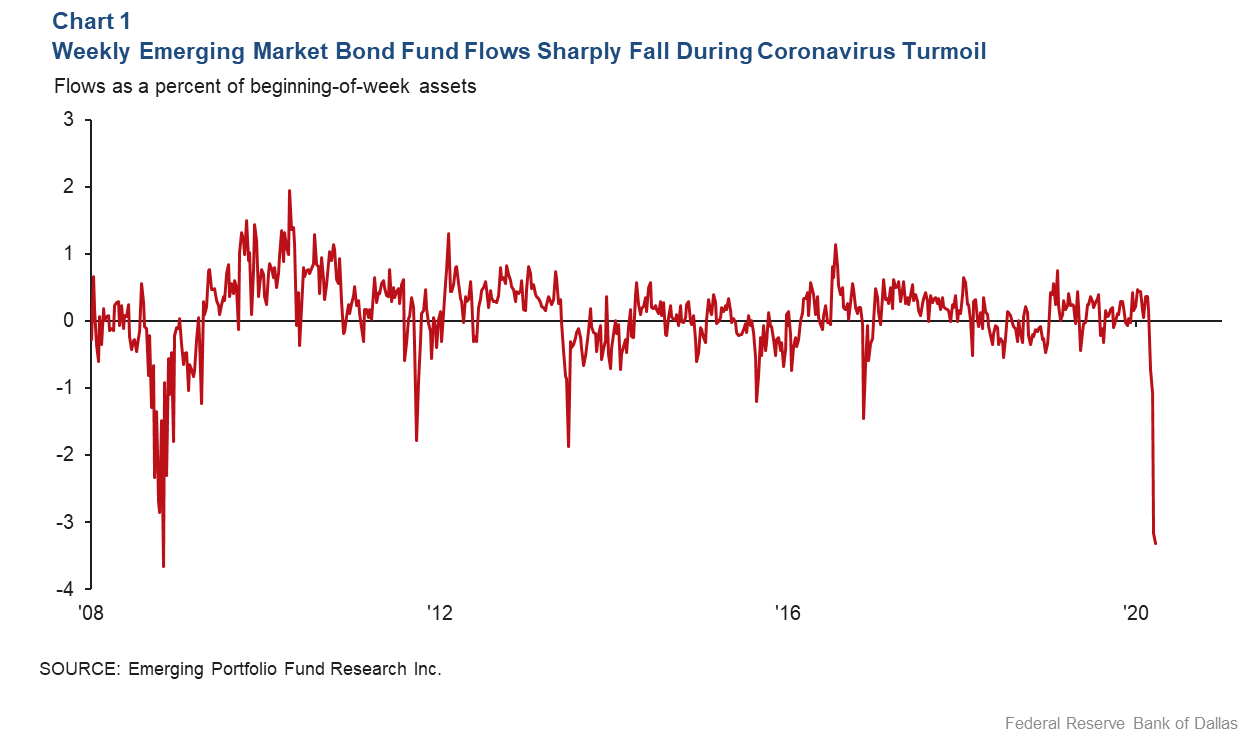

While most aggregate capital flow data won’t be reported for months, we can get a timely snapshot of emerging-market capital flows by looking at weekly data on emerging-market bond exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and mutual fund purchases and redemptions (Chart 1). For the seven days ended March 25, redemptions from emerging-market bond funds were more than 3 percent of total assets.

The outflow was nearly unprecedented in size, eclipsed only by the 3.7 percent outflow during the last week of the global financial crisis in October 2008. The speed with which the most recent activity occurred was notable—emerging-market bond funds had reported net inflows every week of 2020 until the first week in March.

Capital inflow disruption during 2008 global financial crisis

The full extent of the sudden stop in net capital flows into the emerging markets will, of course, depend on the spread of the virus and the success of containment efforts. However, we can look to the 2008 crisis as a guide to which emerging markets are most likely to experience a sudden stop in net capital inflows during the COVID-19 crisis.

Many emerging-market countries require a steady stream of U.S. dollar inflows either to finance a trade deficit or to roll over maturing dollar-denominated liabilities. At times of heightened global risk aversion, finding this dollar financing becomes more difficult. Borrowers in an emerging market must offer larger amounts of the domestic currency in order to obtain the same amount of dollar liquidity, causing the home currency to fall in value.

There is a self-fulfilling nature to international capital flows, as investors do not want to invest in an asset denominated in a currency whose value is expected to fall. Thus, the expectation of currency depreciation leads to diminished capital inflows and ultimately to a decline in the value of the currency. This process, where a fall in capital inflows leads to currency depreciation and then to a further fall in capital inflows, is called a “sudden stop.”

To guard against this external instability, central banks in emerging-market economies hold reserves of liquid foreign currency-denominated assets. These reserves can provide foreign currency liquidity to domestic borrowers at times when it is hard to obtain from foreign lenders, and thus stabilize the value of the local currency. Reserves are a safety net to guard against currency instability and a sudden stop.

Gauging the adequacy of foreign currency-denominated assets

Emerging markets must decide what reserve level is adequate to protect their currency against swings in global risk aversion. Pablo Guidotti, a former deputy finance minister in Argentina, came to a conclusion later popularized by former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan. In a 1999 speech to the World Bank, Greenspan summarized the rule stating “that countries should manage their external assets and liabilities in such a way that they are always able to live without new foreign borrowing for up to one year.”

The rule suggests that emerging-market central banks should hold a stock of foreign currency assets equal to at least the sum of their short-term foreign currency-denominated debt and the current account deficit (the amount by which the value of imported goods and services exceeds the value of exported goods and services).

This leads to a simple measure of a central bank’s reserve adequacy: foreign exchange reserves minus short-term foreign currency-denominated external debt minus the current account deficit.

In a 2018 Dallas Fed Economic Letter, two co-authors and I looked at how reserve adequacy can affect financial stability in an emerging-market economy during a time of Fed monetary tightening. While we are very far from Fed monetary tightening, the same logic can be used to assess financial stability in an emerging-market economy anytime there is a shock that leads to declining emerging-market capital inflows.

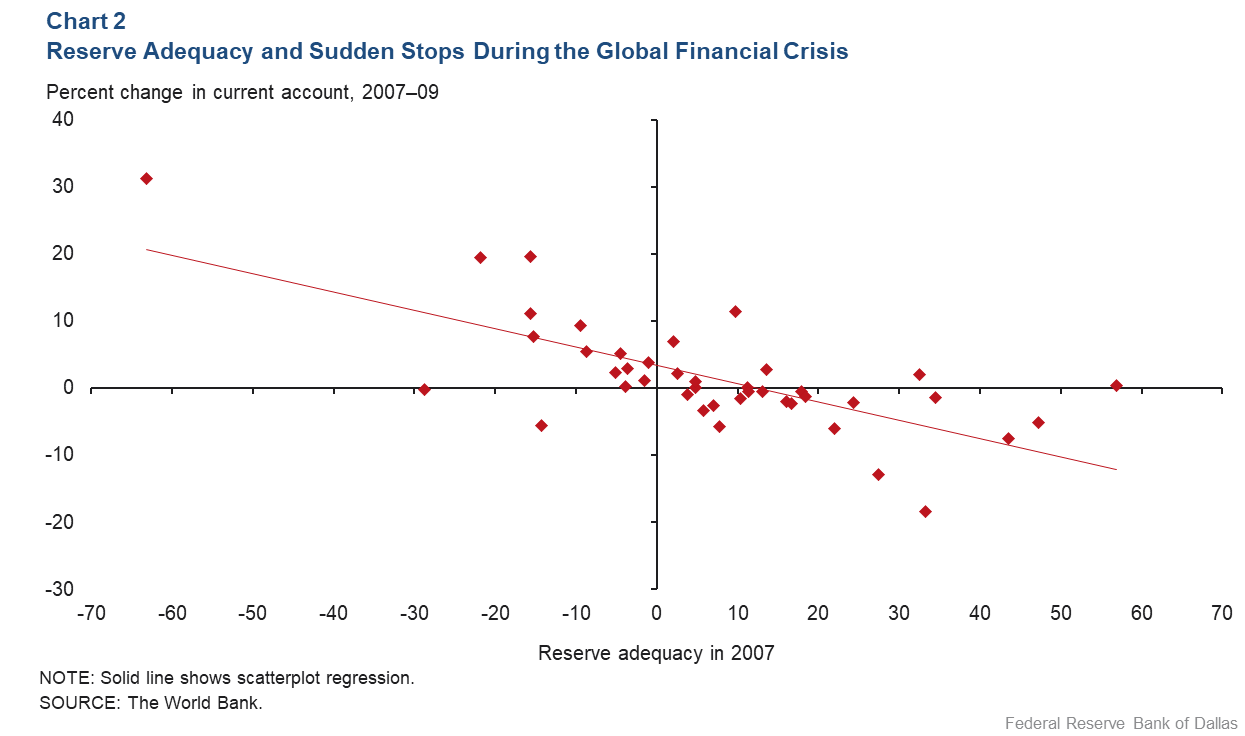

Using the benefit of hindsight, we can see how a country’s reserve adequacy on the eve of the global financial crisis in 2007 affected whether it experienced a sudden stop in net capital inflows during the crisis. In a scatterplot with data from 42 emerging-market economies, the change in a country’s current account from 2007 to 2009 can be plotted against a country’s measure of reserve adequacy in 2007 (Chart 2). The current account is also known as net capital outflows, or equivalently, the negative of the current account is net capital inflows. An increase in the current account is equivalent to a fall in net capital inflows.

The scatterplot regression shows that all else being equal, a country with lower reserve adequacy on the eve of the crisis saw a greater increase in the current account, and thus a greater fall in net capital inflows during the crisis. The trend line in this scatterplot has a negative slope that is highly statistically significant; it implies a fall in reserve adequacy of 10 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2007 is associated with a decline in net capital inflows equal to 2.7 percent of GDP from 2007 to 2009.

Across these 42 emerging-market countries, cross-country differences in reserve adequacy in 2007 can explain 49 percent of the cross-country differences in the fall in net capital inflows during the crisis.

Reserve adequacy and COVID-19 pandemic

It is too soon to know the effect of the current pandemic on capital inflows to emerging-market economies. The severity of the sudden stop will depend largely on the success of virus containment measures. But the experience of 2008 at least tells us how the severity of any sudden stop will be distributed across emerging markets.

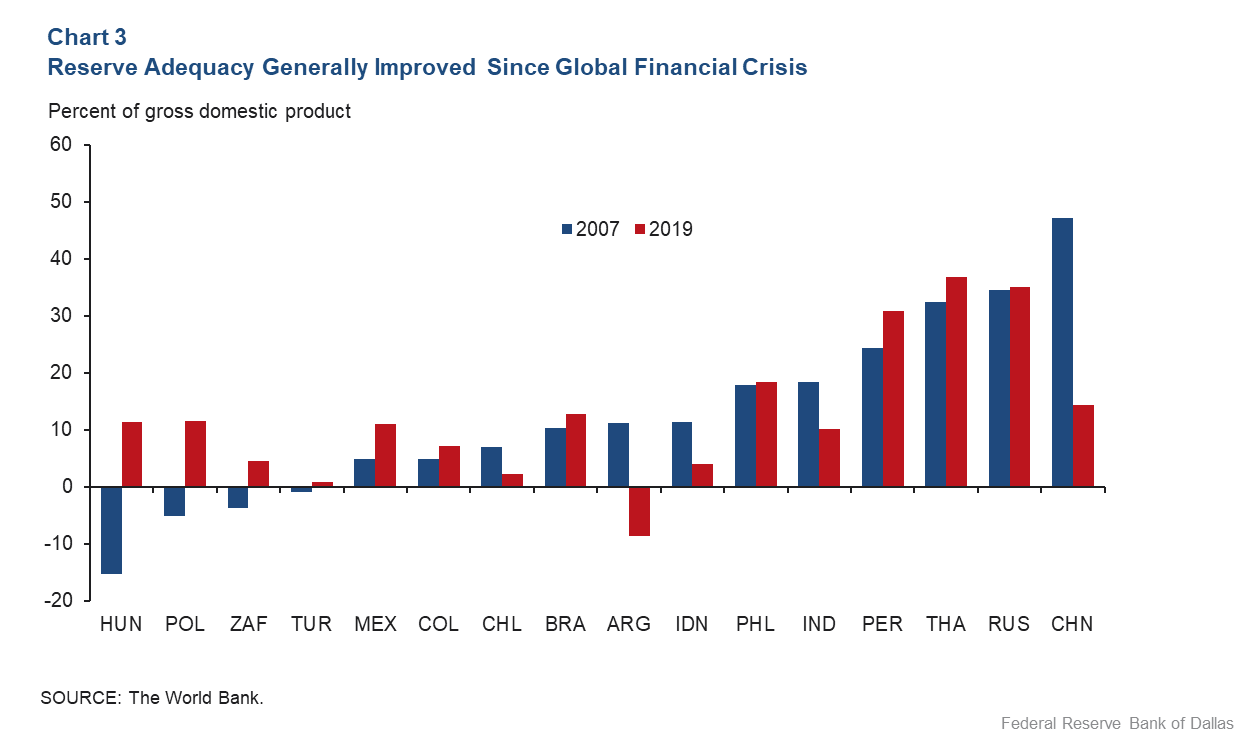

In Chart 3, we plot reserve adequacy in 2007 and 2019 for the major emerging-market economies that we track in the Dallas Fed’s Database of Global Economic Indicators. The chart shows that for most countries, reserve adequacy has improved since 2007. In 2007, four of these 16 countries had negative reserve adequacy, meaning that the central bank did not have the reserves to go without any additional foreign borrowing for one year. Now, only one country has negative reserve adequacy.

There has been a major improvement in reserve adequacy in the Eastern European economies such as Hungary and Poland. Latin American countries—Mexico, and to a certain extent Colombia and Brazil— have improved reserve adequacy. Others—Chile and especially Argentina—have seen reserve adequacy fall to very low levels. Reserve adequacy in South Africa, Turkey and Indonesia is in the low single digits.

The severity of the sudden stop resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic will become evident over the coming weeks and months. In general, emerging markets are better equipped and have higher reserve adequacy now than they did on the eve of the last crisis.

Regions such as Eastern Europe have far more adequate reserves and, therefore, should be spared the sudden stop that the region experienced in 2009. But there are a handful of large emerging-market countries with dangerously low reserve levels. If the fall in capital inflows into emerging markets continues, these countries could face a sudden stop.

About the Author

Scott Davis

Davis is a senior research economist and advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.