Se habla Español: U.S. yet to realize many benefits of a growing bilingual population

The U.S. has the second-largest native Spanish-language population in the world, totaling 54 million out of an overall population of about 328 million. With the broader Hispanic population expected to grow from 60 million to 111 million by 2060, U.S. businesses and workers increasingly recognize that Spanish-language proficiency provides a competitive advantage.

Growing Spanish–English bilingualism in the U.S. opens economic and cultural opportunities. However, the Spanish-only-speaking population in the U.S. faces many challenges that include overcoming often lesser income prospects compared with monolingual English speakers.

Assessing the U.S. native Spanish-language population

The Spanish-language population includes those who grew up in Spanish-speaking homes but have limited proficiency (heritage speakers), those who speak the language at home as their mother tongue (native speakers) and a sizable number of those who learned Spanish as a second (or third or fourth) language.

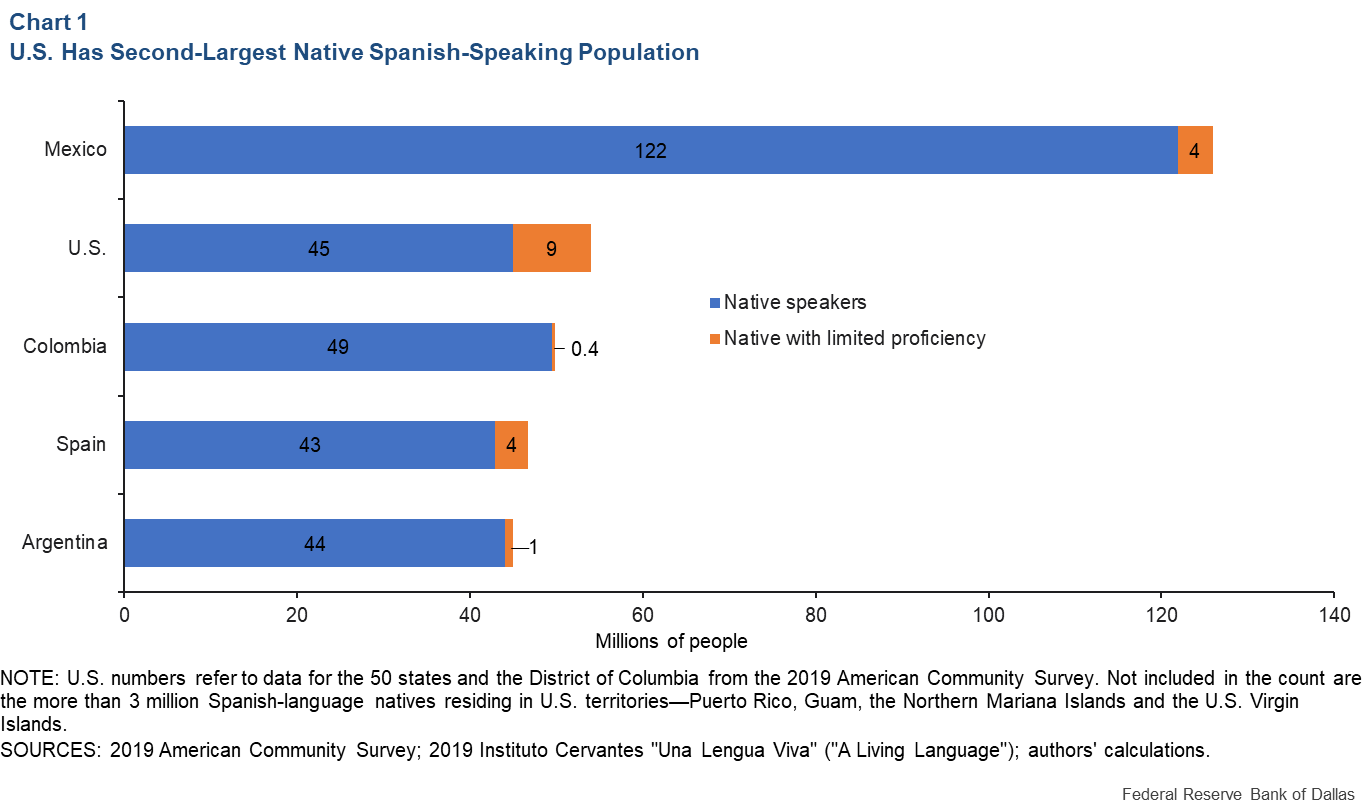

Key resources to track the Spanish-language population in the U.S. are the Census Bureau’s decennial census and its annual American Community Survey (ACS). Spanish is by far the most common native language in the U.S. after English. The U.S. Spanish-language native population is the second largest in the world (Chart 1).

A total of 45 million people in the U.S. speak the language at home (or live in a Spanish-speaking household if under age 5). Another 9 million live in Spanish-speaking households, presumably heritage speakers with limited Spanish-language proficiency. Given that nearly 7.5 million K-12 students in 2015 and 750,000 college students in 2016 were studying Spanish—accounting for half or more of all second-language enrollment—the number of people with some Spanish proficiency likely far exceeds the 54 million natives recorded in the ACS.

Bilingualism aids learning

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Commission on Language Learning, in a recent report exploring the role of second-language education in the U.S., highlighted a number of linguistic, cognitive and academic benefits of bilingualism as well as positive health and sociocultural outcomes.

The report also dispels the popular notion that bilingualism and biliteracy are hindrances because they are cognitively unnatural. Bilingualism, in fact, confers advantages in executive control—the brain’s functions that allow humans to carry out complex tasks such as problem solving, planning and focusing on achieving goals. Children who develop bilingual skills are, thus, more likely to succeed in school.

Foreign-language requirements among many K-12 schools and universities suggest that the benefits of learning languages are well-recognized in academia.

Spanish language as an asset for the U.S. economy

While English continues to be the lingua franca for international business and diplomacy because of its widespread use, the U.S. obtains tangible economic benefits from its large Spanish–English bilingual population.

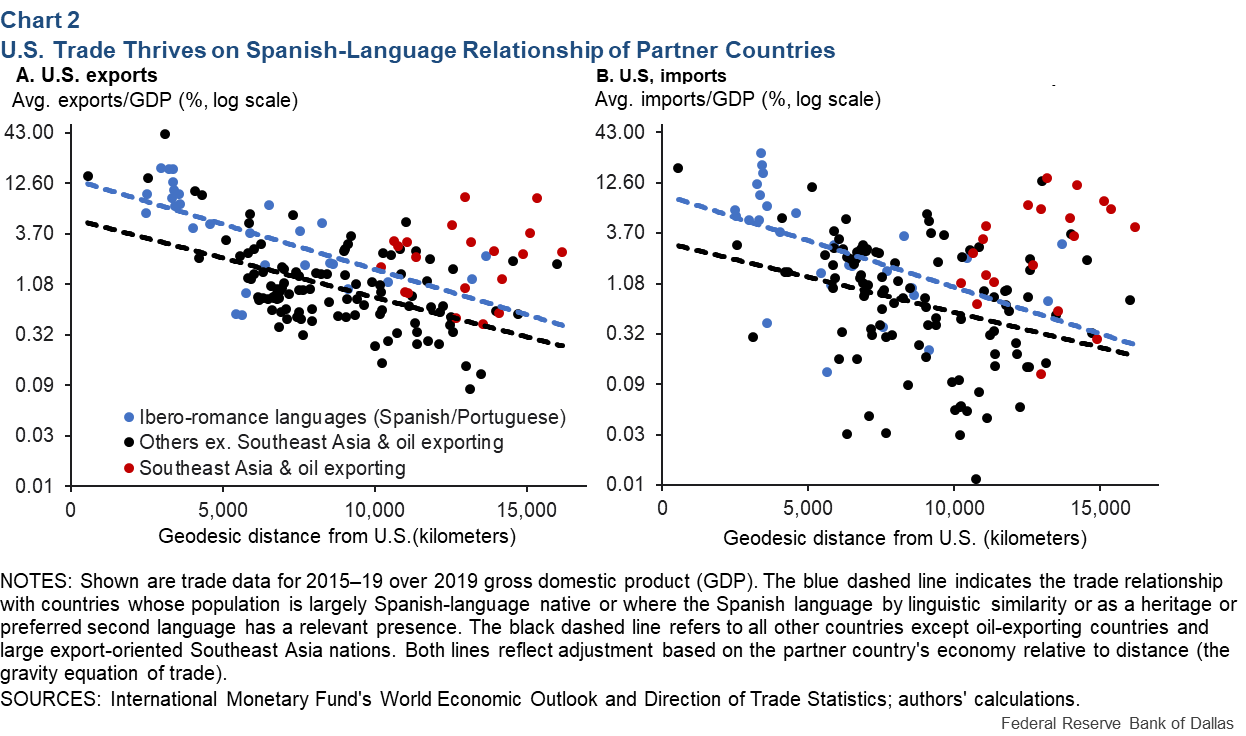

The U.S. shares stronger bilateral trade ties with countries for which Spanish is an important cultural and linguistic bond than would be predicted by their size and distance. Apart from the exporting hubs of Southeast Asia, these trade relationships with Spanish-speaking countries are more intense than those the U.S. has with other countries where English is native or is widely used as a second language (Chart 2).

Our estimates suggest that U.S. exports are $160 billion higher and imports $109 billion greater than would be predicted if the U.S. did not have its strong cultural and linguistic relationship with Spanish-language countries. A Spanish–English bilingual and biliterate workforce is a major asset for the U.S. economy, creating opportunities through trade that benefit all, even non-Spanish speakers.

Some bilingual speakers face socioeconomic challenges

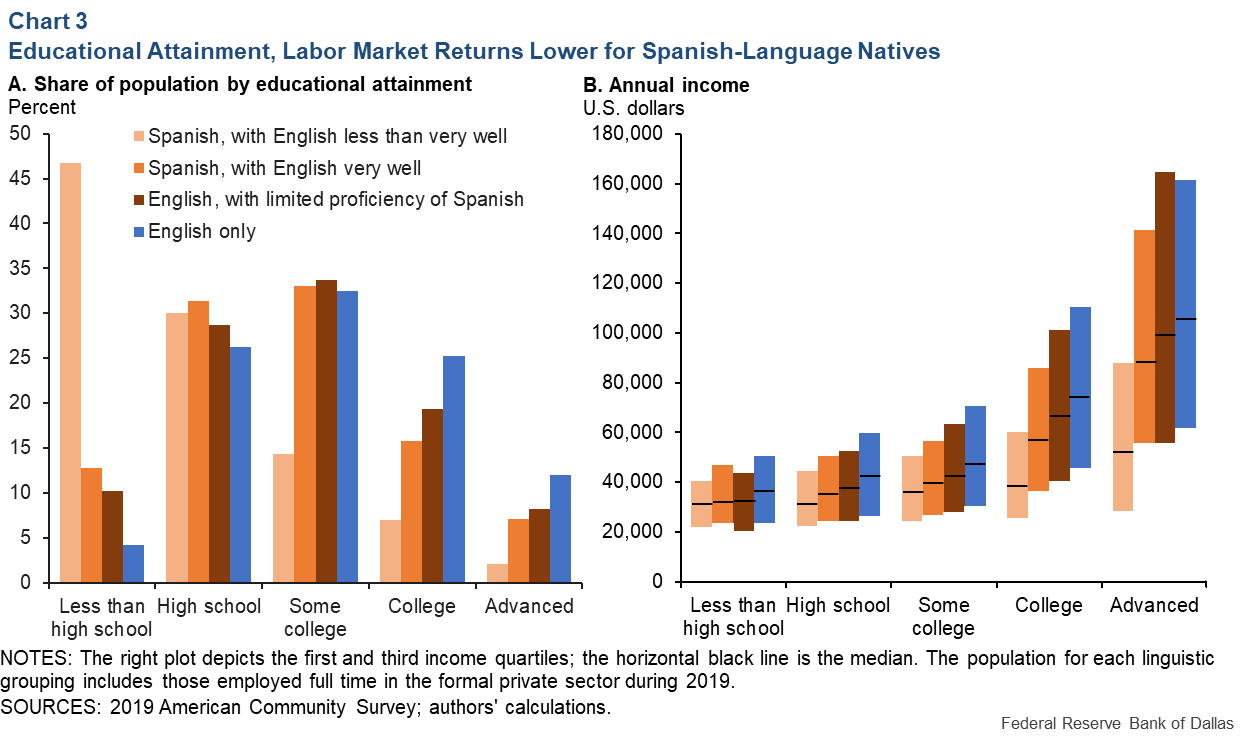

While studies have established the benefits of learning multiple languages, Spanish–English bilingual speakers who are well-integrated culturally and linguistically into the English-speaking majority of the U.S. still confront challenges in leveraging their language skills. The 2019 ACS reflects some of those consequences within the private sector (Chart 3).

English proficiency is strongly correlated with completing a high school education. Relative to English-only speakers, the percentage of Spanish–English and heritage speakers with less than a high school education is higher and the percentage with a college or advanced degree is lower. Additionally, language greatly influences income prospects at all levels of educational attainment.

Income differences become more pronounced at higher education levels, with bilingualism mitigating some, but not all, of the gap with English-language natives. Those differences are robust when controlling for such factors as age, field of study, industry, occupation and gender.

Investing in bilingual education

One explanation for the income shortfall is disparities in early-childhood experiences related to socioeconomic status. Spanish-language natives who report speaking English very well now could have spoken it less than well when younger, thus struggling in English-only schools or advancing their careers more slowly as a result.

Evidence suggests that bilingual children from low-income families perform better on a number of verbal and nonverbal tasks than their single-language counterparts, underscoring the value of investing in bilingual childhood education to raise children’s lifetime income profiles. A growing number of school districts are pursuing this approach—among them, the El Paso Independent School District with its dual-language program—to realize the benefits of bilingualism for the workforce of the future.

Any solution that seeks to improve college graduation rates will take a generation to fully materialize for today’s kindergarteners. More immediately, if greater numbers of Spanish-language natives were to acquire bilingual skills, their lifelong economic prospects would increase dramatically. Bringing their educational attainment to the level of English-speaking natives and closing the income gap with them could increase the disposable income of Spanish-language natives by almost $1 trillion from their current $1.3 trillion (roughly the size of Mexico’s economy).

Recognizing the value of the Spanish language and reducing the frictions that prevent bilingual individuals from realizing their human capital potential in the U.S. marketplace would create beneficial spillover effects benefiting the overall U.S. economy.